Books

Two new books celebrate Old Hollywood glory

‘Elizabeth and Monty: The Untold Story of Their Intimate Friendship’

By Charles Casillo

c.2021, Kensington

$27.00/389 pages

‘The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock’

By Edward White

c.2021, W. W. Norton & Company

$28.95/379 pages

If you’re queer, especially if you’re of a certain age, old Hollywood is embedded in your DNA.

For those of us besotted by classic movies — there can never be too many books about Tinseltown.

Two new books — “Elizabeth and Monty” by Charles Casillo and “The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock” by Edward White — will satisfy your old Hollywood jones.

“Elizabeth and Monty” is the riveting story of the intimate friendship of Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift.

Few people are loved more by the LGBTQ community than Elizabeth Taylor. Who will ever forget Taylor as Martha in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” or as Maggie in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof?”

Taylor raised millions for AIDS research long before any celeb or politico even said the word “AIDS.” People with AIDS weren’t objects of charity to Taylor. She had many queer friends and hung out at gay bars.

Montgomery Clift, who lived from 1920 to 1966, was a talented actor. Because of the time in which he lived, he had to be closeted about his sexuality. Because of the homophobia in the society and Hollywood then, the support of friends was crucial to Clift and other LGBTQ people of that era.

For much of his life, Clift had health problems that caused him pain. Partly as a result of pain, he had issues with drinking and drug addiction. His behavior could be erratic and uncouth. (He had a penchant for eating food off of other people’s plates.)

Despite Clift’s troubles, you become transfixed by his brooding intensity – whether you’re watching him in “The Heiress,” “From Here to Eternity” or “Red River.”

If you have a heartbeat, you’ll feel the chemistry between Clift and Taylor when they’re on screen together in “A Place in the Sun.”

Though Clift was queer and Taylor was hetero, they were the closest of friends.

From the prologue onward, Casillo draws you into their friendship. The book opens on the evening when Clift, driving home from a party, was in a terrible car accident. He’d crashed into a telephone pole.

Taylor went to Clift who was lying bleeding on the road. “Realizing he was choking on his teeth,” Casillo adds, “she instinctively stuck her fingers down his throat and pulled out two broken teeth, clearing the passageway.”

Taylor stuck by Clift when many of his friends distanced themselves from him.

Taylor insisted that Clift be cast in “Reflections in a Golden Eye.” She put up her own salary as insurance for Clift when no one would insure him (because of his health and substance abuse issues).

It’s clear from “Elizabeth and Monty” that Clift was as important to Taylor as she was to him. Their relationship wasn’t sexual, writes Casillo, author of “Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon” and “Outlaw The Lives and Careers of John Rechy.” Yet, there was an emotional intensity – a romantic quality – in their friendship.

Clift nurtured Taylor. He coached Taylor, who he called Bessie Mae, on her acting. He thought Taylor was beautiful, yet understood what it was like for Taylor when people only saw her for her beauty.

“Monty, Elizabeth likes me, but she loves you,” Richard Burton is reported to have said to Clift.

There are good biographies of Taylor – such as William Mann’s “How To Be A Movie Star: Elizabeth Taylor in Hollywood” and of Clift – most notably Patricia Bosworth’s “Montgomery Clift: A Biography.”

Even so, “Elizabeth and Monty” sheds new light on the intense friendship of two queer icons. Check it out. It will imbue you with renewed love and respect not only for Taylor and Clift but for your own friends.

Without Alfred Hitchcock, I’d never make it through the pandemic.

The COVID vaccines are wonderful! But, I’d never get out of my sweatpants without the suspense and glam of Hitchcock’s movies.

Nothing is more comforting than watching serial killer Uncle Charlie in “Shadow of a Doubt” or, with Grace Kelly, James Stewart and Thelma Ritter, observing the murderer in “Rear Window.”

What is more pleasurable than ogling the gorgeous mid-century apartment where a murder has been committed in “Rope?”

Of course, I’m far from alone in loving Hitchcock. Hetero and queer viewers are Hitchcock fans.

Everyone from your straight, straitlaced granny to your bar-hopping queer grandson has had nightmares about the shower scene in “Psycho.” Or had a crush on Cary Grant or Eva Marie Saint in “North by Northwest.”

From the glam in “Rear Window” to Bruno and Guy in “Strangers on a Train,” it’s clear that Hitchcock’s movies have a queer quotient and a special appeal to LGBTQ viewers.

There are more biographies and studies of Hitchcock’s life and work than you could count. Or would want to read.

Yet, “The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock” by Edward White is a good read.

In elegant, precise writing, White illuminates Hitchcock’s life and work by examining 12 aspects of his complex personality. As with all of us, the whole of Hitchcock’s self was more than the components of his personality. Any life, despite the most assiduous biographer’s investigations, remains somewhat of a mystery.

White explores how “Hitchcock” the phenomenon was invented as well as what made Hitchcock the person tick. He carries out this exploration by writing about Hitchcock as everything from “The Fat Man” to “The Murderer” to “The Dandy” to “The Voyeur” to “The Londoner” to “The Family Man” to “The Man of God.”

Hitchcock was a family man who loved his wife, yet, at times, gazed in, to put it mildly an unsavory manner, at some of the actresses such as Tippi Hedren, in his films.

Impeccably dressed in a Victorian-era suite, he plotted films about murder and rape with his wife (and frequent uncredited collaborator) Alma at his side.

For a half century, “Hitchcock’s persona was the active ingredient in the most celebrated of his 53 films,” White writes, “the way Oscar Wilde’s was in his plays, and Andy Warhol’s was in his art.”

Hitchcock stands alone in the Hollywood canon, White writes, “a director whose mythology eclipses the brilliance of his myriad classic movies.”

The span of Hitchcock’s career was immense — from the time of silent films to the 3-D era. His work, White, a “Paris Review” contributor, writes, runs the gamut from thrillers to screwball comedy to horror to film noir to social realism.

Read “The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock.” It’ll take you inside the mosaic of the fab filmmaker’s life and work. Then, break out the popcorn and “Dial M for Murder.”

Books

Two new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

Visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers

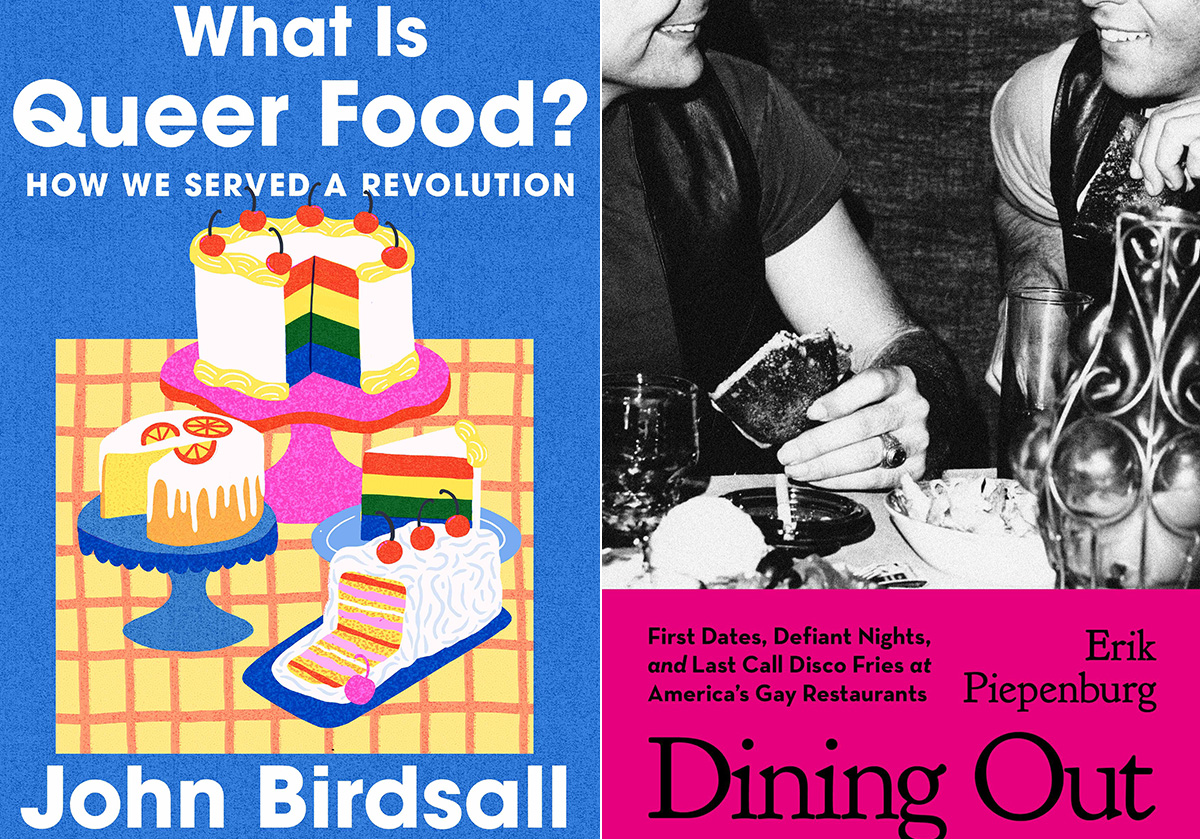

‘What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution’

By John Birdsall

c.2025, W.W. Norton

$29.99/304 pages

‘Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants’

By Erik Piepenburg

c.2025, Grand Central

$30/352 pages

You thought a long time about who sits where.

Compatibility is key for a good dinner party, so place cards were the first consideration; you have at least one left-hander on your guest list, and you figured his comfort into your seating chart. You want the conversation to flow, which is music to your ears. And you did a good job but, as you’ll see with these two great books on dining LGBTQ-style, it’s sometimes not who sits where, but whose recipes were used.

When you first pick up “What is Queer Food?” by John Birdsall, you might miss the subtitle: “How We Served a Revolution.” It’s that second part that’s important.

Starting with a basic gay and lesbian history of America, Birdsall shows how influential and (in)famous 20th century queer folk set aside the cruelty and discrimination they received, in order to live their lives. They couldn’t speak about those things, he says, but they “sat down together” and they ate.

That suggested “a queer common purpose,” says Birdsall. “This is how who we are, dahling, This is how we feed our own. This is how we stay alive.”

Readers who love to cook, bake or entertain, collect cookbooks, or use a fork will want this book. Its stories are nicely served, they’re addicting, and they may send you in search of cookbooks you didn’t know existed.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want to be stuck in the kitchen, you want someone else to bring the grub. “Dining Out” by Erik Piepenburg is an often-nostalgic, lively look at LGBTQ-friendly places to grab a meal – both now and in the past.

In his introduction, Piepenburg admits that he’s a journalist, “not a historian or an academic,” which colors this book, but not negatively. Indeed, his journeys to “gay restaurants” – even his generous and wide-ranging definitions of the term – happily influence how he presents his narrative about eateries and other establishments that have fed protesters, nourished budding romances, and offered audacious inclusion.

Here, there are modern tales of drag lunches and lesbian-friendly automats that offered “cheap food” nearly a century ago. You’ll visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers on holidays. Stepping back, you’ll read about AIDS activism at gay-friendly establishments, and mostly gay neighborhood watering holes. Go underground at a basement bar; keep tripping and meet proprietors, managers, customers and performers. Then take a peek into the future, as Piepenburg sees it.

The locales profiled in “Dining Out” may surprise you because of where they can be found; some of the hot-spots practically beg for a road trip.

After reading this book, you’ll feel welcome at any of them.

If these books don’t shed enough light on queer food, then head to your favorite bookstore or library and ask for help finding more. The booksellers and librarians there will put cookbooks and history books directly in your hands, and they’ll help you find more on the history and culture of the food you eat. Grab them and you’ll agree, they’re pretty tasty reads.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

You’re going to be on your feet a lot this month.

Marching in parades, dancing in the streets, standing up for people in your community. But you’re also likely to have some time to rest and reflect – and with these great new books, to read.

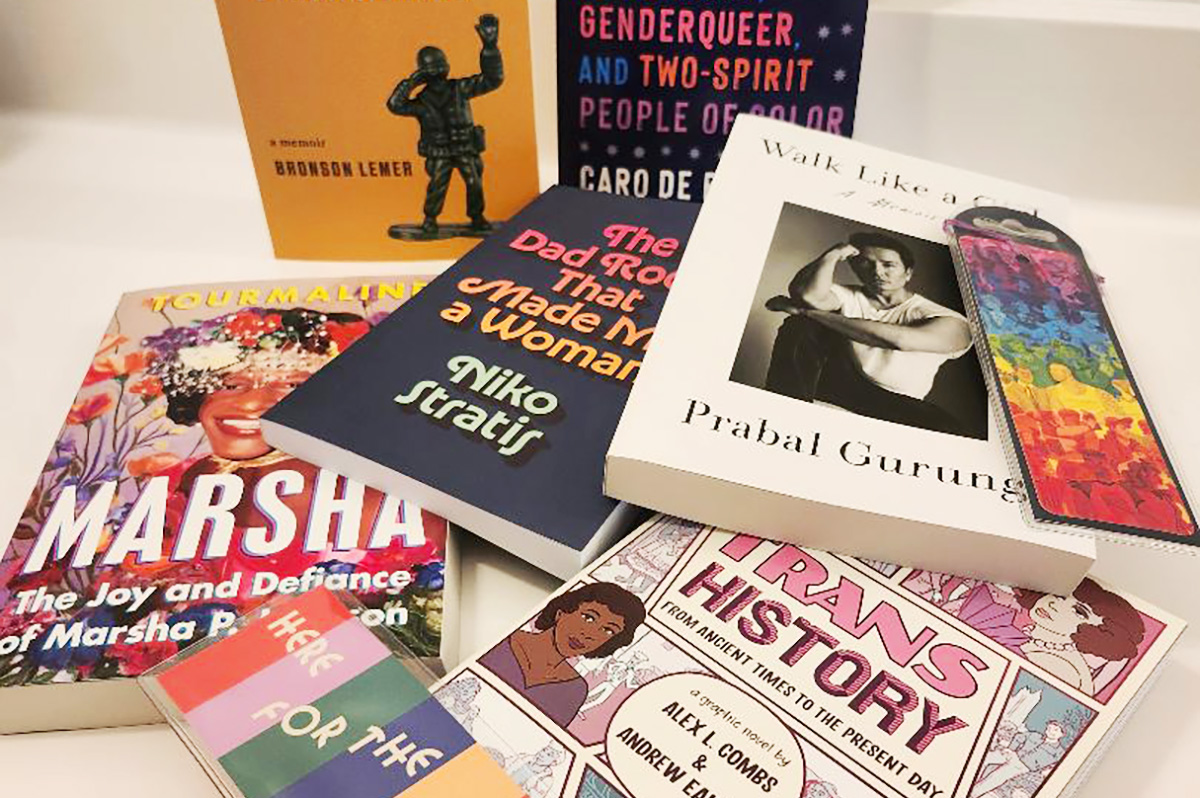

First, dip into a biography with “Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson” by Tourmaline (Tiny Rep Books, $30), a nice look at an icon who, rumor has it, threw the brick that started a revolution. It’s a lively tale about Marsha P. Johnson, her life, her activism before Stonewall and afterward. Reading this interesting and highly researched history is a great way to spend some time during Pride month.

For the reader who can’t live without music, try “The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman” by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press, $27.95), the story of being trans, searching for your place in the world, and finding it in a certain comfortable genre of music. Also look for “The Lonely Veteran’s Guide to Companionship” by Bronson Lemer (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95), a collection of essays that make up a memoir of this and that, of being queer, basic training, teaching overseas, influential books, and life.

If you still have room for one more memoir, try “Walk Like a Girl” by Prabal Gurung (Viking, $32.00). It’s the story of one queer boy’s childhood in India and Nepal, and the intolerance he experienced as a child, which caused him to dream of New York and the life he imagined there. As you can imagine, dreams and reality collided but nonetheless, Gurung stayed, persevered, and eventually became an award-winning fashion designer, highly sought by fashion icons and lovers of haute couture. This is an inspiring tale that you shouldn’t miss.

No Pride celebration is complete without a history book or two.

In “Trans History: From Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Alex L. Combs & Andrew Eakett ($24.99, Candlewick Press), you’ll see that being trans is something that’s as old as humanity. One nice part about this book: it’s in graphic novel form, so it’s lighter to read but still informative. Lastly, try “So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color” by Caro De Robertis (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $32.00) a collection of thoughts, observations, and truths from over a dozen people who share their stories. As an “oral history,” you’ll be glad to know that each page is full of mini-segments you can dip into anywhere, read from cover to cover, double-back and read again. It’s that kind of book.

And if these six books aren’t enough, if they don’t quite fit what you crave now, be sure to ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for help. There are literally tens of thousands of books that are perfect for Pride month and beyond. They’ll be able to determine what you’re looking for, and they’ll put it directly in your hands. So stand up. March. And then sit and read.

a&e features

James Baldwin bio shows how much of his life is revealed in his work

‘A Love Story’ is first major book on acclaimed author’s life in 30 years

‘Baldwin: A Love Story’

By Nicholas Boggs

c.2025, FSG

$35/704 pages

“Baldwin: A Love Story” is a sympathetic biography, the first major one in 30 years, of acclaimed Black gay writer James Baldwin. Drawing on Baldwin’s fiction, essays, and letters, Nicolas Boggs, a white writer who rediscovered and co-edited a new edition of a long-lost Baldwin book, explores Baldwin’s life and work through focusing on his lovers, mentors, and inspirations.

The book begins with a quick look at Baldwin’s childhood in Harlem, and his difficult relationship with his religious, angry stepfather. Baldwin’s experience with Orilla Miller, a white teacher who encouraged the boy’s writing and took him to plays and movies, even against his father’s wishes, helped shape his life and tempered his feelings toward white people. When Baldwin later joined a church and became a child preacher, though, he felt conflicted between academic success and religious demands, even denouncing Miller at one point. In a fascinating late essay, Baldwin also described his teenage sexual relationship with a mobster, who showed him off in public.

Baldwin’s romantic life was complicated, as he preferred men who were not outwardly gay. Indeed, many would marry women and have children while also involved with Baldwin. Still, they would often remain friends and enabled Baldwin’s work. Lucien Happersberger, who met Baldwin while both were living in Paris, sent him to a Swiss village, where he wrote his first novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” as well as an essay, “Stranger in the Village,” about the oddness of being the first Black person many villagers had ever seen. Baldwin met Turkish actor Engin Cezzar in New York at the Actors’ Studio; Baldwin later spent time in Istanbul with Cezzar and his wife, finishing “Another Country” and directing a controversial play about Turkish prisoners that depicted sexuality and gender.

Baldwin collaborated with French artist Yoran Cazac on a children’s book, which later vanished. Boggs writes of his excitement about coming across this book while a student at Yale and how he later interviewed Cazac and his wife while also republishing the book. Baldwin also had many tumultuous sexual relationships with young men whom he tried to mentor and shape, most of which led to drama and despair.

The book carefully examines Baldwin’s development as a writer. “Go Tell It on the Mountain” draws heavily on his early life, giving subtle signs of the main character John’s sexuality, while “Giovanni’s Room” bravely and openly shows a homosexual relationship, highly controversial at the time. “If Beale Street Could Talk” features a woman as its main character and narrator, the first time Baldwin wrote fully through a woman’s perspective. His essays feel deeply personal, even if they do not reveal everything; Lucian is the unnamed visiting friend in one who the police briefly detained along with Baldwin. He found New York too distracting to write, spending his time there with friends and family or on business. He was close friends with modernist painter Beauford Delaney, also gay, who helped Baldwin see that a Black man could thrive as an artist. Delaney would later move to France, staying near Baldwin’s home.

An epilogue has Boggs writing about encountering Baldwin’s work as one of the few white students in a majority-Black school. It helpfully reminds us that Baldwin connects to all who feel different, no matter their race, sexuality, gender, or class. A well-written, easy-flowing biography, with many excerpts from Baldwin’s writing, it shows how much of his life is revealed in his work. Let’s hope it encourages reading the work, either again or for the first time.

-

U.S. Supreme Court4 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court4 days agoSupreme Court upholds ACA rule that makes PrEP, other preventative care free

-

U.S. Supreme Court4 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court4 days agoSupreme Court rules parents must have option to opt children out of LGBTQ-specific lessons

-

Congress5 days ago

Congress5 days agoSenate parliamentarian orders removal of gender-affirming care ban from GOP reconciliation bill

-

District of Columbia5 days ago

District of Columbia5 days agoMan sentenced to 15 years in prison for drug deal that killed two DC gay men