South America

Meet Argentina’s special envoy for LGBTQ and intersex rights

Alba Rueda is a transgender woman, long-time activist

Editor’s note: The Washington Blade interviewed Alba Rueda before the murder of Alejandra Ironici, a prominent transgender activist, in Santa Fe on Aug. 22 and the attempted assassination of Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in Buenos Aires on Sept. 1.

Argentina is a pioneer in the implementation of laws and public policies that support LGBTQ and intersex rights.

The country in 2010 became the first in South America to extend marriage rights to same-sex couples. Argentina in 2021 became the second country in the Americas to offer nonbinary national ID cards.

A transgender rights law and a labor quota for trans people, among other things, have been implemented since then. These initiatives, in most cases, have inspired neighboring countries to recognize LGBTQ and intersex people.

Argentina this year created a position within the country’s Foreign Affairs Ministry that focuses exclusively on the promotion of LGBTQ and intersex rights abroad.

Alba Rueda, a well-known queer activist, on May 2 became Argentina’s first-ever Special Representative on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. The U.S., the U.K., Italy and Germany are the four other countries with people in their respective governments who specifically promote LGBTQ and intersex rights abroad.

Rueda, 46, is a trans woman who was born in Salta province in northern Argentina.

She moved to Buenos Aires with her family when she was a teenager. Rueda became an activist at an early age and has held various public positions over the last two decades.

Rueda was previously Argentina’s first undersecretary of diversity policies in the Women, Gender and Diversity Ministry. She is the first trans woman to hold a senior position in the country’s government.

Rueda explained to the Washington Blade that her position is one “that deals exclusively with foreign policy regarding diversity policies.”

“We are within the State’s structure,” she said. “We are in a very unique position within this ministry’s political agenda.”

For her, the advances in LGBTQ and intersex rights in Argentina have great relevance because activists and the movements of which they are a part had good strategies that influenced the political arena.

“The trasvestí and transgender community knew how to anchor (themselves) in the militancy of human rights,” she said. “The 2012 gender identity law is undoubtedly a milestone for all of Latin America because of its content. [It is] one of the first laws that set very high standards of rights in the world and that were really developed by the trans community in the sociopolitical organizations in which we participate.”

Rueda recalled that in 2006, before any legislation in favor of sexual and gender diversity took effect, the trans population won a legal battle when the Supreme Court ruled Asociación Lucha por la Identidad Travesti (ALITT), a trans advocacy group, could obtain legal status.

“This was a fundamental step within the political agenda and from then on a whole process of decriminalization began,” Rueda recalled to the Blade.

The advancement of LGBTQ and intersex rights in Argentina since then has not stopped, and that is why Rueda wants to replicate this work in countries across South America and around the world. Argentina, in fact, over the last year has hosted a variety of Global Equality Caucus-led workshops that have focused on the elimination of so-called conversion therapy.

“We are a team under my leadership, where we are working integrally with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, carrying out different lines of work to strengthen the multilateral policies that our country has around certain agendas, as in the United Nations, for example,” she emphasized.

Regarding her efforts with other Latin American countries, Rueda said she will work to improve the quality of life of LGBTQ and intersex people based on efforts in Argentina.

“We are going for a coordination of State policy around LGBT rights, around living conditions; not only the promotion of rights, but of public policies that modify the structure of that inequality around living conditions,” Rueda stressed.

“There are several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean that do not have a gender identity law. With equal marriage, with a trans labor quota law and what we have here is not only an experience around public policies, but the evidence that this really strengthens and prevents other types of violence,” she added. “This is basically Argentina’s contribution to Latin American cooperation.”

Finally, she stressed that “it has to do precisely with the strengthening of a line of work which is to demonstrate the evidence that the greater the rights and recognition, the better not only the quality of democracy, but also the better the living conditions of our community and the reduction of violence.”

South America

Man convicted of killing Daniel Zamudio in Chile seeks parole

Raúl López Fuentes in 2013 sentenced to 15 years in prison

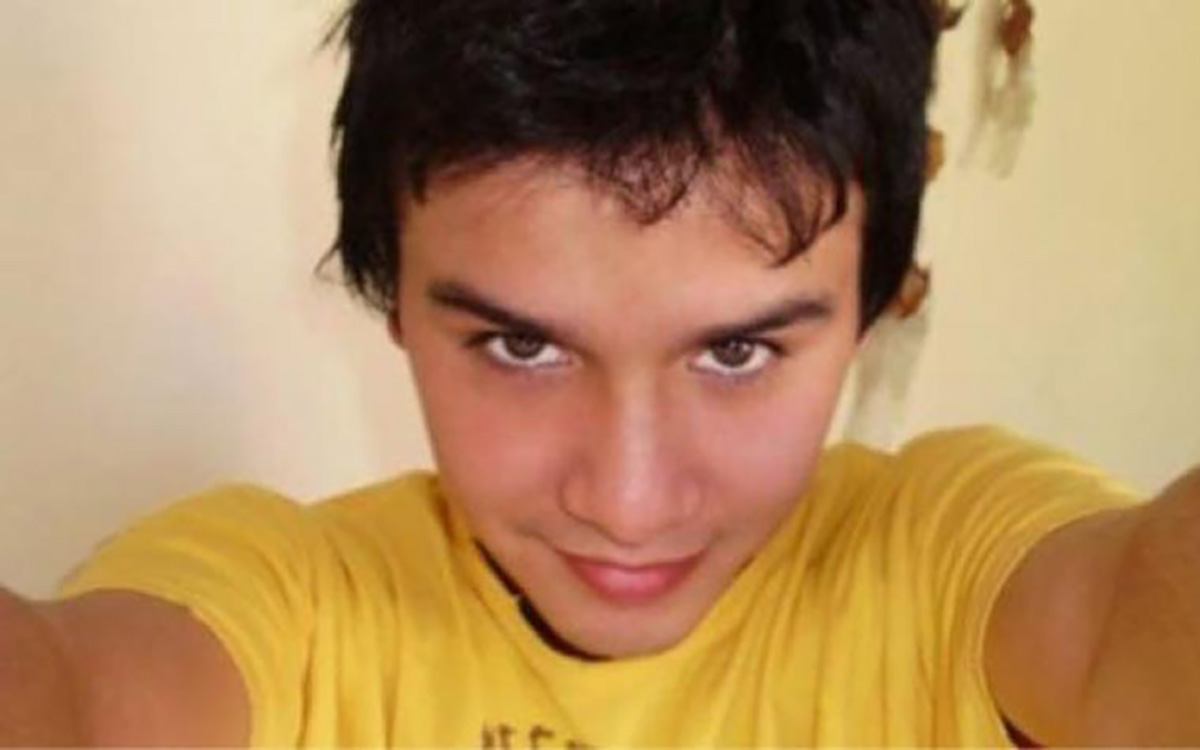

One of the four men convicted of murdering a young gay man in the Chilean capital in 2012 is seeking parole.

Raúl López Fuentes in 2013 received a 15-year prison sentence after he was convicted of killing Daniel Zamudio.

Zamudio was a young Chilean man who became a symbol of the fight against homophobic violence in his country and around the world after López and three other young men with alleged ties to a neo-Nazi group beat him for several hours in Santiago’s San Borja Park on March 2, 2012. Zamudio succumbed to his injuries a few weeks later.

The attack sparked widespread outage in Chile and prompted a debate over homophobia in the country that highlighted the absence of an anti-discrimination law. Lawmakers in the months after Zamudio’s murder passed a law that bears Zamudio’s name.

Patricio Ahumada received a life sentence, while López and Alejandro Angulo Tapia are serving 15 years in prison. Fabían Mora Mora received a 7-year prison sentence.

López has asked the Seventh Santiago Guarantee Court to serve the last three years of his sentence on parole. Zamudio’s family and Jaime Silva, their lawyer who works with the Movement for Homosexual Integration and Liberation, oppose the request.

Movilh represented Zamudio’s family after his murder.

Zamudio’s mother, Jacqueline Vera, during an exclusive interview with the Washington Blade said López’s petition “provoked all the anguish, all the commotion of his time.”

“It was very cruel because in fact two days before we were at Daniel’s grave, where it was 12 years since his death and the beating,” said Vera. “He really does not deserve it.”

“We have gone through very difficult moments,” she added.

The mother, who later created a foundation to eradicate discrimination in Chile, was emphatic in indicating that she and her family “do not accept the release of this guy because he is a danger to society and a danger to ourselves.”

“At the last hearing where they were sentenced, they told us that we are going to remember them when they get out,” said Vera. “They threatened us with death. There is a video circulating on social networks where they were in front of me and they laughed and made fun of me. They told me that I remembered that I had three more children.”

Regarding the possibility that the Chilean justice system will allow López to serve the remaining three years of his sentence on parole, Vera said “with the benefits here in Chile, which is like a revolving door where murderers come and go, it can happen.”

“In any case, I don’t pretend, I don’t accept and I don’t want (López) to get out, I don’t want (López) to get out there,” she said. “We are fighting for him not to get out there because I don’t want him to get out there. And for me it is not like that, they have to serve the sentence as it stands.”

LGBTQ Chileans have secured additional rights since the Zamudio Law took effect. These include marriage equality and protections for transgender people. Advocacy groups, however, maintain lawmakers should improve the Zamudio Law.

“We are advocating for it to be a firmer law, with more strength and more condemnation,” said Vera.

When asked by the Washington Blade about what she would like to see improved, she indicated “the law should be for all these criminals with life imprisonment.”

South America

Argentine president announces state institutions can no longer use inclusive language

Activists condemn Javier Milei’s anti-LGBTQ policies

In a move that has generated concern and criticism throughout the country, Argentine President Javier Milei has announced government institutions can no longer use inclusive language and gender-specific references in their public policies.

This decision comes on top of other controversial measures, such as the closure of the Women, Gender and Diversity Ministry, and an announcement to shutter the country’s National Institute against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism.

Former Diversity Undersecretary Alba Rueda, a transgender woman who was the country’s special envoy for LGBTQ issues under former President Alberto Fernández’s government, and gay Congressman Esteban Paulón, in exclusive interviews with the Washington Blade discussed the impact of Milei’s announcement and the impact it will have on Argentine society in terms of human rights and protections for queer people.

“The State had been using the gender perspective and inclusive language to make visible the presence of women in key roles and to recognize nonbinary identities,” Rueda said. “This measure not only erases those advances, but also excludes people who are already recognized by the State in their nonbinary gender identities.”

Rueda noted Congress more than a decade ago “passed the gender identity law, which states in its first article that the State will respect the gender identity of all persons. After changes were made in the structure of the State to be able to generate identity documents, a series of court rulings that recognize nonbinary people in their nonbinary identity arose in 2016, and this (and) that remained unresolved during the Macrista government without recognizing the identity of nonbinary people.”

She pointed out Fernández’s government in 2021 issued Decree 746, which recognized “people with nonbinary identities, gender fluid and those who avoid naming their gender before the State.”

“The State already recognizes this citizenship and here comes that the prohibition of inclusive language excludes in the way of naming people who are already recognized by the State and that effectively the recognition of their gender identity is the condition of not being binary,” said Rueda. “So, the decree is in force, the law is in force, there are nonbinary people with their documents, but who today are not being named in all state documents.”

Paulón said the prohibition of inclusive language is a gesture of violence towards LGBTQ communities.

“Inclusive language has given entity and identity to an important part of the Argentine population,” he said. “This measure represents an act of harassment and violence towards those who identify with inclusive language, including the queer and LGBTQ+ collective.”

“Language is a social and cultural construction, and in Argentina today inclusive language represents and has given entity and identity to an important segment of the population and to a series of social collectives,” added Paulón. “Therefore, something that is not created by decree can hardly be eliminated by decree.”

The congressman told the Blade that Milei’s government announcement was “something that was clearly going to happen.”

“I don’t see the government campaigning in inclusive language or celebrating diversity,” said Paulón.

Milei’s decision has generated intense debate in Argentina, with critics arguing these measures represent a step backwards in the protection of human rights and an attack on diversity and inclusion. Milei’s supporters, on the other hand, defend these measures as part of an effort to promote conservative policies and reinforce national identity.

“It is very serious because it limits the exercise of citizenship and affects the nonbinary population, women and the trans population that is not recognized within the gender binarism,” said Rueda.

She noted Milei during his presidential campaign raised these issues, and has decided to implement policies that harm women and LGBTQ people.

“This is the gravity that is lived today in Argentina, that the Argentine head of state puts in confrontation and reduction of rights to women and LGBTIQ+ people,” Rueda added.

This ban on inclusive language and gender-specific policies has been announced against the context of increased political and social polarization in Argentina. With inflation at alarming levels and an economy in crisis, Milei’s government has sought to consolidate its base by adopting controversial measures that have generated division and unrest in Argentine society.

“That is the institutional and democratic gravity today in Argentina, that the head of state attacks and creates internal enemies and that position is accompanied by the media, amplifying a negative message about our communities,” Rueda said. “Of course that translates into social networks, but it also translates into the attacks that we LGBTIQ+ people experience in the public sphere.”

South America

Argentina’s president seeks to dismantle anti-discrimination agency

Activists have sharply criticized Javier Milei’s move

Argentinian President Javier Milei’s proposed closure of his country’s National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism has sparked widespread criticism among LGBTQ activists and human rights defenders.

Alba Rueda, the former Undersecretary of Diversity Policies in the Women, Gender and Diversity Ministry who was also the country’s Special Representative on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity under Alberto Fernández’s government, and gay Congressman Esteban Paulón in exclusive interviews with the Washington Blade talked about the Feb. 22 announcement’s implications and the impact it will have on Argentine society at a time marked by an acute economic, political and social crisis.

Rueda said INADI’s closure is a serious setback in the fight against discrimination and the advancement of human rights in Argentina.

“INADI is a human rights agency that has been in force in Argentina for almost 30 years, which emerged as a response to the international attacks we suffered,” she pointed out. “This body has been fundamental in the attention of discrimination cases, including strategic litigation such as the (murder) of Diana Sacayán (a prominent transgender rights activist) in 2015.”

Paulón said INADI’s closure is part of a broader policy of harassment towards diversity and state institutions that Milei’s government has carried out.

“INADI, along with the already eliminated Women Ministry, has been fundamental in the defense of the rights of LGBTQ+ and queer people,” said Paulón.

“In practical facts, the government cannot close INADI because INADI has been created by a law and it would require another law to close it,” he added. “Therefore, it has been raised that there is going to be a restructuring of personnel, a readjustment of resources that are going to continue processing complaints, but that they are going to pass to the orbit of the Justice Ministry, where INADI already is, but let’s say, they would pass without the institutionalism and that it would remain as an empty shell until the government achieves the consensus of a law to eliminate.”

Both agreed that INADI’s closure represents a serious setback in the protection of human rights in Argentina and a threat to the most vulnerable groups in society, including LGBTQ people. They also stressed Milei’s government has used this announcement as part of a broader strategy to dismantle democratic institutions and the country’s human rights agenda.

INADI cannot be closed unilaterally, despite the announcement, because a law created it and another statute would be required to dismantle it. There are, however, concerns the government may attempt to dismantle the institution or reduce its operational capacity.

“The decision to close INADI responds to an ideological position,” said Rueda. “They believe that INADI is the policeman of this, the ideological policeman. It is a body that functions autonomously whose president is appointed by the Congress and which also has a board of directors of social organizations.”

Critics of Milei’s government argue INADI’s closure is part of a strategy to consolidate power and repress dissent. They say the government is using the economic crisis as a pretext to implement authoritarian measures that limit civil liberties and weaken democratic institutions.

Milei’s supporters, on the other hand, defend the move as part of a broader effort to reduce public spending and promote liberal economic policies. They argue INADI’s closure is necessary to eliminate waste and corruption in government, and that its impact on human rights and LGBTQ protection is overstated.

“For LGTB people in particular, the closure of INADI would leave us without a place where we could basically receive attention in the face of discrimination,” Rueda pointed out. “And another issue that INADI also did is that it generated public policy recommendations or developed public policies for the prevention and awareness of these changes that have to take place in society.”

“So, not only do we run out of spaces for denunciation, but also of where to change this culture of discrimination, culture of discrimination that are present in the labor market that Milei presents or points out to you, as a success and that this is self-regulated,” she added.

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoReenactment of first gay rights picket at White House draws interest of tourists

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoNew D.C. LGBTQ+ bar Crush set to open April 19

-

Arizona2 days ago

Arizona2 days agoAriz. governor vetoes anti-transgender, Ten Commandments bill

-

Africa4 days ago

Africa4 days agoUgandan activists appeal ruling that upheld Anti-Homosexuality Act