District of Columbia

Recovery at the Triangle Club

Coming together as a group to fight a common addiction

On Sunday, between the Dupont Italian Kitchen, where the tables are filled with the boozy brunches of the kickball gays, and Mikko, where a young couple is celebrating their anniversary with some Champagne, the door to a row-house opens, and all at once, a crowd pours forth onto the stairs. Only the stairs keep on filling. These folks aren’t leaving. They’ve only left the building to come to the stairs, just to chat. It’s as though 100 people all decided to go for a smoke out front, all at the same time. But if you ask them why they’re there, you’ll get only the vaguest of answers. “We’re just coming from a meeting,” one will say. “It’s a clubhouse,” says another.

There are good reasons for this vagueness. The Triangle Club is a center for queer folk to attend recovery meetings: Overeaters Anonymous, Alcoholics Anonymous, Crystal Meth Anonymous, Sexual Compulsives Anonymous. It’s part of the very mission of these groups to protect the privacy of their members. But these groups also want those in the queer community who need the support to know that they’re there. And so the folks at the Triangle Club were kind enough to welcome the Blade into their space for a few meetings, to see how things worked and shed some light on what they’re all about.

The Club had its kickoff meeting in 1988, during the AIDS crisis. Churches weren’t particularly enthusiastic about hosting gay recovery meetings in their back rooms. And so the Club sought to provide a safe place for those meetings to take place. At the time of the club’s founding, it was estimated that gays and lesbians were twice as likely to report problems with alcohol abuse than heterosexuals. One would hope that things might have changed in the intervening years. But according to a government report released this summer, that figure has barely improved. (The government report did not collect any statistics on transgender people.)

Of course there is no single reason queer people develop problems with drugs and alcohol. But one in particular struck me, especially as a reason I heard coming from a lot of the younger folk at the Triangle Club. “I thought meth was a prerequisite for going out,” said one. “I thought that’s what you did.” Another said, “I drank to find community. And then I drank to numb myself when I didn’t find it in the gay community.” Again and again, I heard stories about turning to drugs and alcohol as a way of finding connection, and as a way of coping with the failure to find connection.

And so while I heard a lot of gratitude for the role the meetings at the Triangle Club played in people’s recovery, I also heard a lot of gratitude for the community of the Triangle Club itself. It wasn’t just that the Club helped people turn away from an unhealthy way of solving their problems. It’s that it gave them what they were really looking for in the first place: a community they could call their own.

Improbably, as I left a meeting of Crystal Meth Anonymous, I found myself wishing to be an addict in recovery. To have a place to share things that would go unsaid among friends and family, let alone therapists. To take part, week after week, in one another’s mission for a more fulfilling life. To be present for the absolute raucousness, as when one gentleman described living on meth as “wearing a fur coat into a swimming pool,” and then “turning the wave-machine on.” To hear the applause that only someone four days sober could receive. But what kind of destructive, life-threatening wish was I making? I couldn’t possibly be serious.

Many of us in the queer community are exhausted by drinking, if not drugging, our way into it. That exhaustion might not rise to the level of addiction, but this has the perverse consequence of not driving us to seek alternative forms of belonging. One of the men I interviewed kept talking of the “sober community,” and my ears perked up. Perhaps there was a broader community of folks, of which those in recovery were only a part, that wasn’t centered around substance use.

“The sober community absolutely extends beyond the Triangle Club,” he told me. “There are a bunch of other gay meetings that go on.” This wasn’t exactly what I hoped to hear. What a sorry state we’re in, I couldn’t help but feel that to be part of the sober community was to be in recovery. As though the community of substance use were so mandatory that it had to drive you to your own personal edge in order for you to find community in sobriety.

The Triangle Club should not be overly romanticized, and they’d be the first to tell you. People talked of trying to find fellowship at the club in the past, and not necessarily succeeding. Being one of two Black people in the room, only for the other to drop out of the program. Or of the demands of service, dragging yourself out late Friday night to chair a meeting, or sponsoring someone for the first time and being scared that you aren’t the right one to advise them. But I think it’s a testament to the space that these things could be said in the space. The meetings aren’t a place of mandatory optimism, but honest experience. And what good is a meeting for sharing honest experience if you can’t share your negative experiences too?

I had hoped, as part of this feature, to attend a meeting of Sexual Compulsives Anonymous. The two meetings I appealed to were kind enough to hold a vote on whether they would open their doors—but in the end they opted to remain private. One gentleman from the meetings volunteered to share a little of what these meetings were all about. Recovery meetings in general depend on coming together as a group to fight a common addiction. But “S” meetings, as the gentleman described them, can’t take “coming together” lightly, nor a “common addiction” lightly.

To begin with, sexual addiction is not as straightforwardly defined as addiction to drugs or alcohol. What sobriety is for one person is not what sobriety is for another. One person might be trying to curtail a masturbation habit. But for others? “That simply isn’t an option,” the gentleman said. And unlike recovery meetings for substances, which can ban substances from the room, the same can’t as easily be said for “S” meetings. We’re sexual beings, and so inevitably, to bring yourself into a room is to bring sexuality along with it. The recovery meetings at the Triangle Club usually end with the group joining hands to say the serenity prayer. But this can’t be a given at “S” meetings, where joining hands might be violating someone’s boundary.

With the pandemic waning, most recovery meetings have slowly started to transition away from video format back to in-person. But “S” meetings have been more reluctant to do so, and most have stuck with a hybrid format. One veteran of Al-Anon voiced his relief at coming back to the rooms. “You can’t hug a square!” I suspect that’s the very reason “S” meetings have been slow to return.

Part of my disappointment in not attending the “S” meetings was how central they seemed to be to a queer recovery organization. Substance abuse might disproportionately affect the queer community, but it is the addicts who are queer, not the addictions. If the addiction is to love or sex, however, the addiction itself is inextricably queer. Aren’t the “S” meetings the heart, in a sense, of the Triangle Club? But a conversation with a gentleman from Alcoholics Anonymous had me rethinking this. “[Accepting you’re an alcoholic,] it’s similar to coming out as gay,” he said. “There are people out there who view it as a moral failing, but it’s just part of who I am.”

The experience of coming out is so central to being queer. How could coming out as an addict have nothing whatsoever to do with it? The same story of a newfound, authentic life was as common to the folks at the Triangle Club as it would be to anyone who comes out as queer.

(CJ Higgins is a postdoctoral fellow with the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute at Johns Hopkins University.)

District of Columbia

Gay ANC member announces candidacy for Ward 1 D.C. Council seat

Community leader Brian Footer seeking seat held by Brianne Nadeau

Gay Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner Brian Footer, a community activist who has been involved for many years in local and national government affairs, has announced his candidacy for the Ward 1 D.C. Council seat up for election in 2026.

Footer, a Democrat, will be running in the city’s June 2, 2026, Democratic primary for the Ward 1 Council seat, but it is uncertain whether he will be running against incumbent Ward 1 Council member Brianne Nadeau (D). Nadeau has not yet announced if she plans to run for re-election for a fourth term following her 12 years on the Council.

Nadeau has been a longtime vocal supporter of the LGBTQ community.

If Footer were to win the primary and the November 2026 general election, he would become the Council’s second openly gay member. Ward 5 Council member Zachary Parker (D) is currently the 13-member Council’s only gay member.

Footer is a three-term ANC commissioner who currently serves as Chair of ANC 1E, which represents the city’s Adams Morgan neighborhood.

“Brian has worked at every level of government — federal, state, and local — building a career rooted in public service, aging policy, and inclusive urban planning,” a statement on his campaign website says.

“I’m running for Council because too many people in Ward 1 are doing everything right and still feel ignored by the city they call home,” Footer states on his website.

“I’m running because we can do better,” his statement continues. “That means making housing more affordable, addressing homelessness with real solutions, and keeping our neighborhoods safe with smart, community focused strategies.”

When contacted by the Washington Blade for comment, Nadeau said she was not ready at this time to discuss her plans about running again or about Footer’s candidacy.

“The primary is a ways away, and I’m very focused right now on the budget and the stadium deal and all the work that we’re doing at the Council,” she told the Blade. “So, I really haven’t had time to turn to my plans. So, as a result, I’m also not going to be commenting on anybody else who is determined that they’re running at this time.”

She first won election to the Council in 2014 after she defeated four-term gay Ward 1 Council member Jim Graham in the Democratic primary after Graham became embroiled in an ethics controversy.

In the 2022 Democratic primary Nadeau defeated gay challenger Salah Czapary in a three-candidate race, by a margin of 48.5% of the vote compared to Czapary’s 30.9%.

With the third candidate, Sabel Harris, receiving 20.4%, the outcome showed that the two challengers had a combined total vote count higher than Nadeau.

Further details of Footer’s candidacy can be accessed from his campaign website, brianfooterdc.com.

District of Columbia

Gay GOP group hosts Ernst, 3 House members — all of whom oppose Equality Act

Log Cabin, congressional guest speakers mum on June 25 event

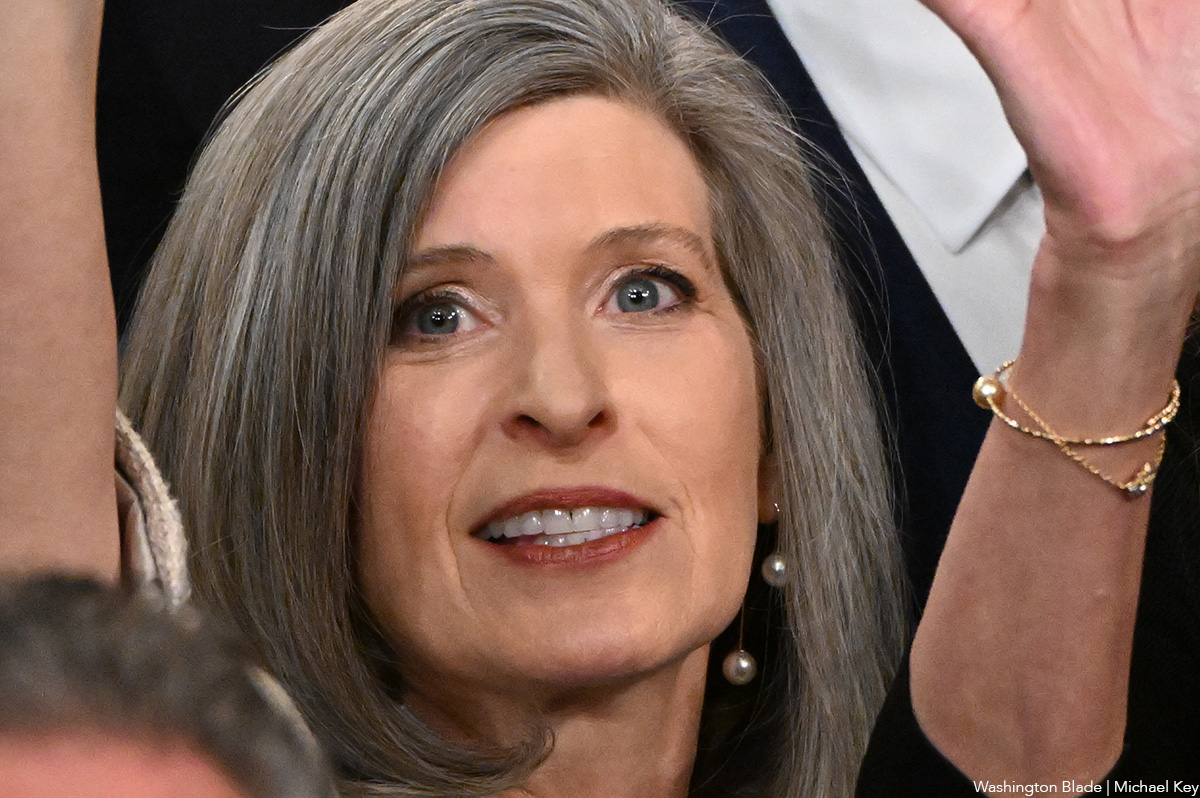

U.S. Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) and three women Republican members of the U.S. House appeared as guest speakers at the June 25 meeting of Log Cabin Republicans of D.C., the local chapter of the national LGBTQ Republican group with that same name.

The U.S. House members who joined Ernst as guest speakers at the Log Cabin meeting were Celeste Maloy (R-Utah), Kat Cammack (R-Fla.), and Julia Letlow (R-La.).

Neither D.C. Log Cabin Republicans President Andrew Minik nor spokespersons for Ernst or the three congresswomen immediately responded to a request by the Washington Blade for comment on the GOP lawmakers’ appearance at an LGBTQ GOP group’s meeting.

“Please join us for an inspiring evening as we celebrate and recognize the bold leadership and accomplishments of Republican women in Congress,” a D.C Log Cabin announcement sent to its members states.

“This month’s meeting will highlight the efforts of the Republican Women’s Caucus and explore key issues such as the Protection of Women and Girls In Sports Act and the broader fight to preserve women’s spaces in society,” the message says.

It was referring to legislation pending in Congress calling for banning transgender women from participating in women’s sports events.

According to media reports, Ernst and the three congresswomen have expressed opposition to the Equality Act, the longstanding bill pending in Congress calling for prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in the areas of employment, housing, and public accommodations.

The Log Cabin announcement says the meeting was scheduled to take place at the Royal Sands Social Club, which is a restaurant and bar at 26 N St., S.E. in the city’s Navy Yard area.

D.C. Log Cabin member Stuart West, who attended the meeting, confirmed that Ernst and the three congresswomen showed up and spoke at the event.

“It was a good turnout,” he said. “I would definitely say probably 30 or 40 people attended.” West added, “Four women came to talk to a group of mostly gay men. That’s something you don’t see very often.”

District of Columbia

D.C. police seek public’s help in July 5 murder of trans woman

Relative disputes initial decision not to list case as hate crime

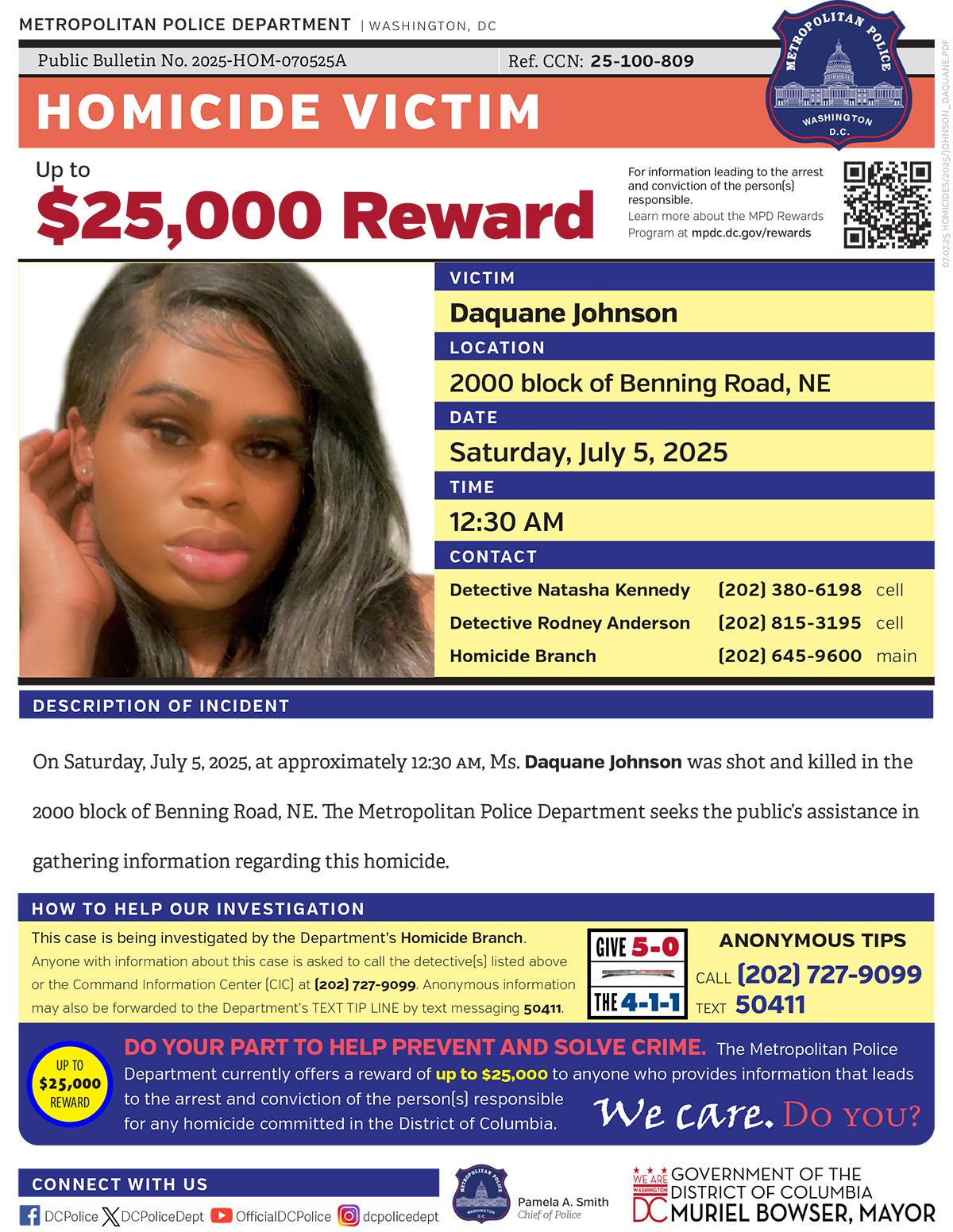

D.C. police are seeking help from the public in their investigation into the murder of a transgender woman who they say was shot to death at about 12:30 a.m. on Saturday, July 5, on the 2000 block of Benning Road, N.E.

But the police announcement of the fatal shooting and a police report obtained by the Washington Blade do not identify the victim, 28-year-old Daquane ‘Dream’ Johnson of Northeast D.C., as transgender. And the police report says the shooting is not currently listed as a suspected hate crime.

It was local transgender activists and one of Johnson’s family members, her aunt, who confirmed she was transgender and said information they obtained indicates the killing could have been a hate crime.

“On Saturday, July 5, at approximately 12:51 a.m., Sixth District officers were flagged down in the 2000 block of Benning Road, Northeast, for an unconscious female,” a July 5 D.C. police statement says. “Upon arrival, officers located an adult female victim suffering from gunshot wounds,” it says.

“D.C. Fire and EMS responded to the scene and transported the victim to a local hospital where after all lifesaving efforts failed and the victim was pronounced dead,” the statement says.

A separate police flyer with a photo of Johnson announces an award of $25,000 was being offered for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the person or persons responsible for the murder.

The flyer identifies D.C. police Homicide Detective Natasha Kennedy as being the lead investigator in the case and says anyone with information about the case should contact her at 202-380-6198.

Longtime D.C. transgender rights advocate Earline Budd told the Blade that one of the police investigators contacted her about the case and that she also spoke to Detective Kennedy. Budd said police confirmed to her that Johnson was a transgender woman.

One of Johnson’s family members, Vanna Terrell, who identified herself as Johnson’s aunt, told the Blade that Johnson used the first name of Dream and had planned to legally adopt that name instead of Daquane but had not gotten around to doing so.

Terrell said she and other family members learned more about the incident when one of two teenage high school students who knew Johnson’s brother contacted a friend and told the friend that they recognized Johnson as they witnessed the shooting. Terrell said the friend then called her to tell her what the friend learned from the two witnesses.

According to Terrell, the witnesses reportedly saw three men approach Johnson as Johnson walked along Benning Road and one of them called Johnson a derogatory name, leading Terrell to believe the men recognized Johnson as a transgender woman.

Terrell said one of the witnesses told the friend, who spoke to Terrell, that the man who shot Johnson kept shooting her until all of the bullets were fired. Budd, who said she spoke to Terrell, who also told her what the witnesses reported, said she believed the multiple shots fired by the shooter was an “overkill” that appears to have been a hate crime. Terrell said she too believes the murder was a hate crime.

In response to an inquiry from the Blade, Officer Ebony Major, a D.C. police spokesperson, stated in an email, “At this point there is nothing in the investigation that indicates the offense was motivated by hate or bias.”

Terrell said a memorial gathering to honor Johnson’s life was scheduled to be held Saturday, July 12, at River Terrace Park, which is located at 500 36th St., N.E. not far from where the shooting occurred.

-

Federal Government2 days ago

Federal Government2 days agoTreasury Department has a gay secretary but LGBTQ staff are under siege

-

Virginia3 days ago

Virginia3 days agoDefying trends, new LGBTQ center opens in rural Winchester, Va.

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoGay GOP group hosts Ernst, 3 House members — all of whom oppose Equality Act

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoD.C. police seek public’s help in July 5 murder of trans woman