Books

Graphic novel ‘Smahtguy’ offers timely bio of Barney Frank

Cartoonist Eric Orner makes policy suspenseful

When he was in high school, gay cartoonist Eric Orner, who makes his graphic novel debut with “Smahtguy: The Life and Times of Barney Frank,” didn’t like the food in the school cafeteria. “The principal was always talking about how good we had it,” Orner told the Blade in a recent interview.

“But the food was deep fried – inedible,” Orner added, “even for us [teens].”

To protest the food, Orner called it out with humor in the comic strip he drew for the school newspaper. “Having this platform to express yourself subversively and sarcastically to authority,” Orner said, “gave me a buzz.”

Like a hound born to hunt, Orner has always loved to draw. A proclivity for subverting the powers that be with humor has been etched in his veins from birth.

“Drawing is what I love to do,” said Orner, who is in his 50s, “It’s been that way since I was a kid.”

If there’s a problem, Orner will sit for an hour and draw. “I’ve been most brave – most outspoken when I’m drawing.”

Orner’s drawing and respect for outspokenness are in splendid form in his graphic novel “Smahtguy,” a biography of queer icon Barney Frank.

As the House (at this writing), repeatedly fails to elect a Speaker, nothing could be more timely than “Smahtguy.”

Frank, who came out as gay in the Boston Globe in 1987, was a Democratic member of the House of Representatives from Massachusetts from 1981 to 2013.

When you hear “bio of a queer and political icon,” you might well think: boring, musty, wonky tome. But you needn’t worry. “Smahtguy” is a page-turner about Frank, a politician who disliked politics, but loved policy. Orner, in this bio, does the nearly impossible: he makes policy suspenseful. Orner makes you want to know how Frank used wonkiness in issues from housing to banking to help people.

Equally important, Orner makes you see and care about Frank’s personal life – from his background and family, to his coming out to his periods of loneliness to his marriage to Jim, his longtime partner.

“Publishers Weekly,” in a starred review, called “Smahtguy,” “an astute, richly detailed profile” of Frank.

Orner jokes that he has “dual citizenship.” He has roots in two cities – Chicago and Boston.

He was born and grew up in Chicago. “My Dad’s family is in Chicago,” Orner said, “My Mom’s family is in Massachusetts.”

Orner, who lives now in New York and spends time with his partner in upstate New York, is acclaimed for his groundbreaking comic strip “The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green.”

The strip, first published in 1989, ran in 100 papers (gay press and about 25 alternative weeklies). “The Blade was the second paper to run it,” Orner said.

“The work of the gay press was so important to who we became as a people,” Orner said, “I’m Jewish. The Yiddish press was so important to Jewish people at the turn of the last century.”

In 1989, before “Queer as Folk,” “Modern Family,” let alone “Fire Island” or “Bros,” there was nothing like it. Except Alison Bechdel’s trailblazing comic strip “Dykes to Watch Out For,” which ran from 1983 to 2008.

Back then, you didn’t see drawings and stories about queer people in comic strips. Especially, narratives of LGBTQ people dating, being out, dealing with break-ups, coping with AIDS, working – living ordinary lives.

Ethan was a good, but not a fabulous, guy. He wasn’t a hunky athlete or movie star. Break-ups more than picture-perfect romances were his lot. You saw yourself when you read “The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green,” which was made into a movie of the same name in 2005.

Orner didn’t come out early in his life. “I knew early,” he said, “but the Midwest is a little more conservative.”

There was the Stonewall Uprising. But that wasn’t part of the culture at his high school. “My high school was so conformist,” Orner said, “it could have been the 1950s.”

After high school, Orner moved to Boston where he went to college and law school. “I’ve lived in Boston, New York, D.C., and Los Angeles,” he said, “but I’ve never lived as an adult gay person in Chicago.”

Orner’s father, now deceased, was a straight guy who revered Hugh Hefner and Sean Connery. “One of the most important cultural icons,” Orner said, “when my Dad was in his prime in the 1960s, was Playboy.”

At first, Orner’s father just couldn’t conceive of the fact that he had a gay son. “But, my Dad was a contrarian,” Orner said, “weirdly, he was the sort of person who likes to upset the apple cart.”

If there was a rule that could be broken, he’d want to break it, Orner added.

“My Dad could not get his head around my being gay,” Orner said, “until my first Ethan Green book [a collection of his Ethan Green comic strips] came out.”

One day, one of Orner’s father’s law partners saw a copy of the Ethan Green book at a bookstore at O’Hare Airport. “The straight-laced partner had a meltdown in my father’s office,” Orner said, “over how terrible it was to see my Dad’s name on the book.”

Once Orner’s nonconformist Dad saw his partner’s pearl-clutching, Orner said, “he got his head around [his son’s being gay].”

Orner’s mother was very political. Politics runs in his family, Orner said.

“The minute I came out, unbeknown to me,” Orner said, “my Mom had joined PFLAG.”

Orner has great affection for Boston. He lived there for 25 years. He’d see the Orson Welles Cinema between Harvard and Central Square as he walked toward Bay Street. The first drawing Orner sold was to the “The Phoenix,” a (now defunct) Boston alternative weekly.

He loved cartooning. But, “like most artists, I needed a day job,” Orner said.

Orner and Barney Frank crossed paths at a cocktail party. At that time, Cardinal Bernard Law (since disgraced because of his involvement in the Catholic Church sex abuse scandal) was the Archbishop of Boston.

“I was making wiseass shit about the Cardinal,” Orner said, “Barney said it was a funny cartoon – to call him if I needed a job.”

Orner took Frank up on his offer. For 20 years, on and off, he worked for Frank as staff counsel and press secretary for the House Financial Services Committee.

In between stints working for Frank, Orner worked for Disney. “Disney taught me to draw fast,” he said, “and to capture the essence of something – like a gesture – quickly.”

Frank was your classic tough boss, Orner said. “Barney was interested in policy,” he said, “he wanted government to be professional.”

Orner admires Frank, but “sometimes he makes mistakes,” he said.

“Smahtguy” isn’t an authorized biography. After working on it for three years, Orner packaged it up and sent it to Frank. “Barney had only a few, 19, I think, minor corrections,” Orner said.

One was over a drawing of a daily racing form in Frank’s mother’s purse. “Barney said I had to change that,” Orner said, “because his aunts gambled, but his Mom never gambled.”

Orner strived to convey Frank’s greatness – his political achievement and personality – warts and all. “I very much didn’t want to do hagiography,” he said.

With the news as terrible as it often is now, Orner’s art is more needed than ever.

“I never feel things are so fraught or horrible that I don’t want to draw about them,” Orner said in an email to the Blade.

“And, a lot of my work over the past 10 years has been about Israel and Palestine,” he added.

In comics, creators are able to tap into the full range of human emotions, Orner said.

“Watching the House Freedom caucus somehow convert a single clown car into an epic interstate pile up,” Orner said, “is for this longtime Capitol Hill staffer pretty funny.”

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Embracing the chaos can be part of the fun

‘Make Sure You Die Screaming’ offers many twists and turns

‘Make Sure You Die Screaming’

By Zee Carlstrom

c.2025, Random House

$28/304 pages

Sometimes, you just want to shut the door and forget what’s on the other side.

You could just wipe it from your memory, like it didn’t occur. Or create an alternate universe where bad things never happen to you and where, as in the new novel “Make Sure You Die Screaming” by Zee Carlstrom, you can pretend not to care.

Their mother called them “Holden,” but they’d stopped using that name and they hadn’t decided what to use now. What do you call an alcoholic, queer, pessimistic former ad executive who’s also “The World’s First Honest White Man,” although they no longer identify as a man? It’s a conundrum that they’ll have to figure out soon because a cop’s been following them almost since they left Chicago with Yivi, their psychic new best friend.

Until yesterday, they’d been sleeping on a futon in some lady’s basement, drinking whatever Yivi mixed, and trying not to think about Jenny. They killed Jenny, they’re sure of it. And that’s one reason why it’s prudent to freak out about the cop.

The other reason is that the car they’re driving was stolen from their ex-boyfriend who probably doesn’t know it’s gone yet.

This road trip wasn’t exactly well-planned. Their mother called, saying they were needed in Arkansas to find their father, who’d gone missing so, against their better judgment, they packed as much alcohol as Yivi could find and headed south. Their dad had always been unique, a cruel man, abusive, intractable; he suffered from PTSD, and probably another half-dozen acronyms, the doctors were never sure. They didn’t want to find him, but their mother called…

It was probably for the best; Yivi claimed that a drug dealer was chasing her, and leaving Chicago seemed like a good thing.

They wanted a drink more than anything. Except maybe not more than they wanted to escape thoughts of their old life, of Jenny and her death. And the more miles that passed, the closer they came to the end of the road.

If you think there’s a real possibility that “Make Sure You Die Screaming” might run off the rails a time or three, you’re right. It’s really out there, but not always in a bad way. Reading it, in fact, is like squatting down in a wet, stinky alley just after the trash collector has come: it’s filthy, dank, and profanity-filled. Then again, it’s also absurd and dark and philosophical, highly enjoyable but also satisfying and a little disturbing; Palahniuk-like but less metaphoric.

That’s a stew that works and author Zee Carlstrom stirs it well, with characters who are sardonic and witty while fighting the feeling that they’re unredeemable losers – which they’re not, and that becomes obvious.

You’ll see that all the way to one of the weirdest endings ever.

Readers who can withstand this book’s utter confusion by remembering that chaos is half the point will enjoy taking the road trip inside “Make Sure You Die Screaming.”

Just buckle up tight. Then shut the door, and read.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

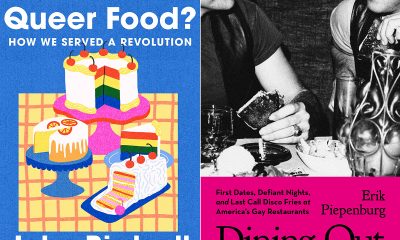

Two new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

Visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers

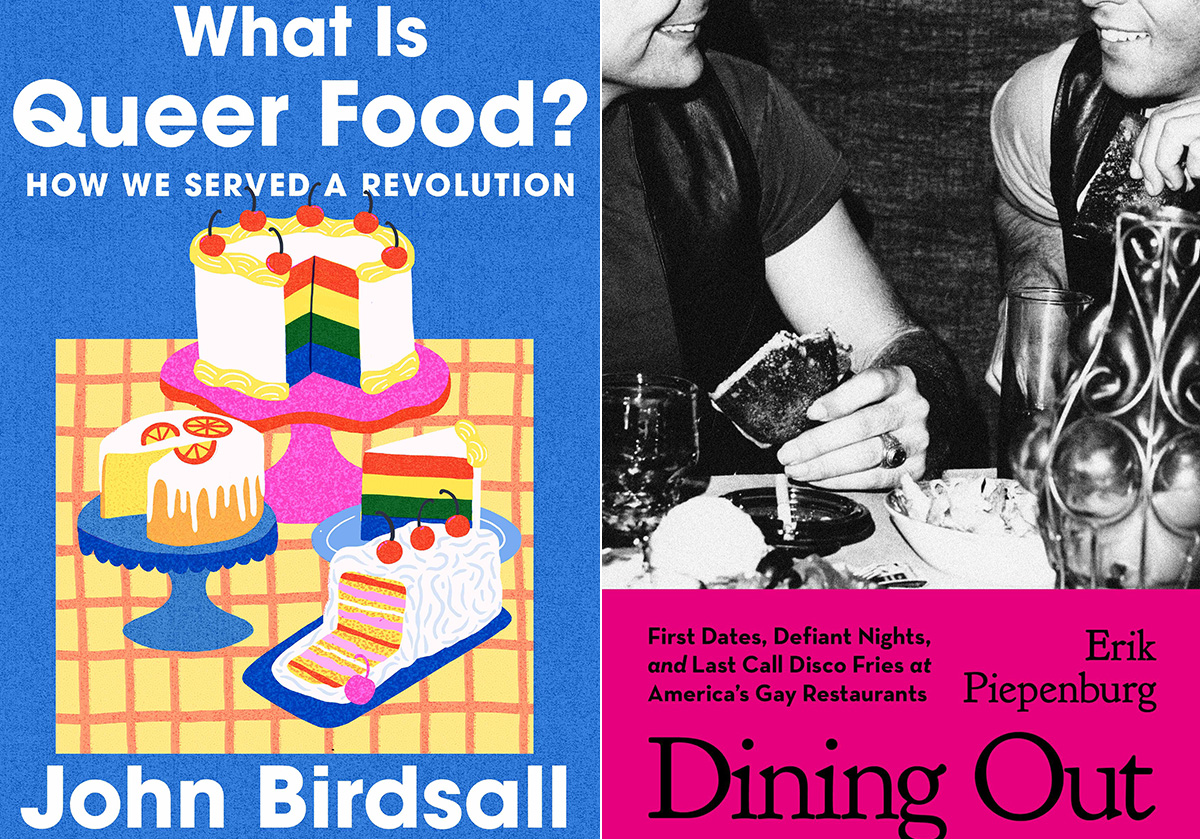

‘What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution’

By John Birdsall

c.2025, W.W. Norton

$29.99/304 pages

‘Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants’

By Erik Piepenburg

c.2025, Grand Central

$30/352 pages

You thought a long time about who sits where.

Compatibility is key for a good dinner party, so place cards were the first consideration; you have at least one left-hander on your guest list, and you figured his comfort into your seating chart. You want the conversation to flow, which is music to your ears. And you did a good job but, as you’ll see with these two great books on dining LGBTQ-style, it’s sometimes not who sits where, but whose recipes were used.

When you first pick up “What is Queer Food?” by John Birdsall, you might miss the subtitle: “How We Served a Revolution.” It’s that second part that’s important.

Starting with a basic gay and lesbian history of America, Birdsall shows how influential and (in)famous 20th century queer folk set aside the cruelty and discrimination they received, in order to live their lives. They couldn’t speak about those things, he says, but they “sat down together” and they ate.

That suggested “a queer common purpose,” says Birdsall. “This is how who we are, dahling, This is how we feed our own. This is how we stay alive.”

Readers who love to cook, bake or entertain, collect cookbooks, or use a fork will want this book. Its stories are nicely served, they’re addicting, and they may send you in search of cookbooks you didn’t know existed.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want to be stuck in the kitchen, you want someone else to bring the grub. “Dining Out” by Erik Piepenburg is an often-nostalgic, lively look at LGBTQ-friendly places to grab a meal – both now and in the past.

In his introduction, Piepenburg admits that he’s a journalist, “not a historian or an academic,” which colors this book, but not negatively. Indeed, his journeys to “gay restaurants” – even his generous and wide-ranging definitions of the term – happily influence how he presents his narrative about eateries and other establishments that have fed protesters, nourished budding romances, and offered audacious inclusion.

Here, there are modern tales of drag lunches and lesbian-friendly automats that offered “cheap food” nearly a century ago. You’ll visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers on holidays. Stepping back, you’ll read about AIDS activism at gay-friendly establishments, and mostly gay neighborhood watering holes. Go underground at a basement bar; keep tripping and meet proprietors, managers, customers and performers. Then take a peek into the future, as Piepenburg sees it.

The locales profiled in “Dining Out” may surprise you because of where they can be found; some of the hot-spots practically beg for a road trip.

After reading this book, you’ll feel welcome at any of them.

If these books don’t shed enough light on queer food, then head to your favorite bookstore or library and ask for help finding more. The booksellers and librarians there will put cookbooks and history books directly in your hands, and they’ll help you find more on the history and culture of the food you eat. Grab them and you’ll agree, they’re pretty tasty reads.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

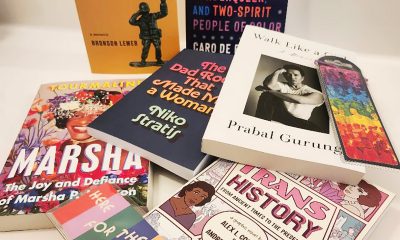

You’re going to be on your feet a lot this month.

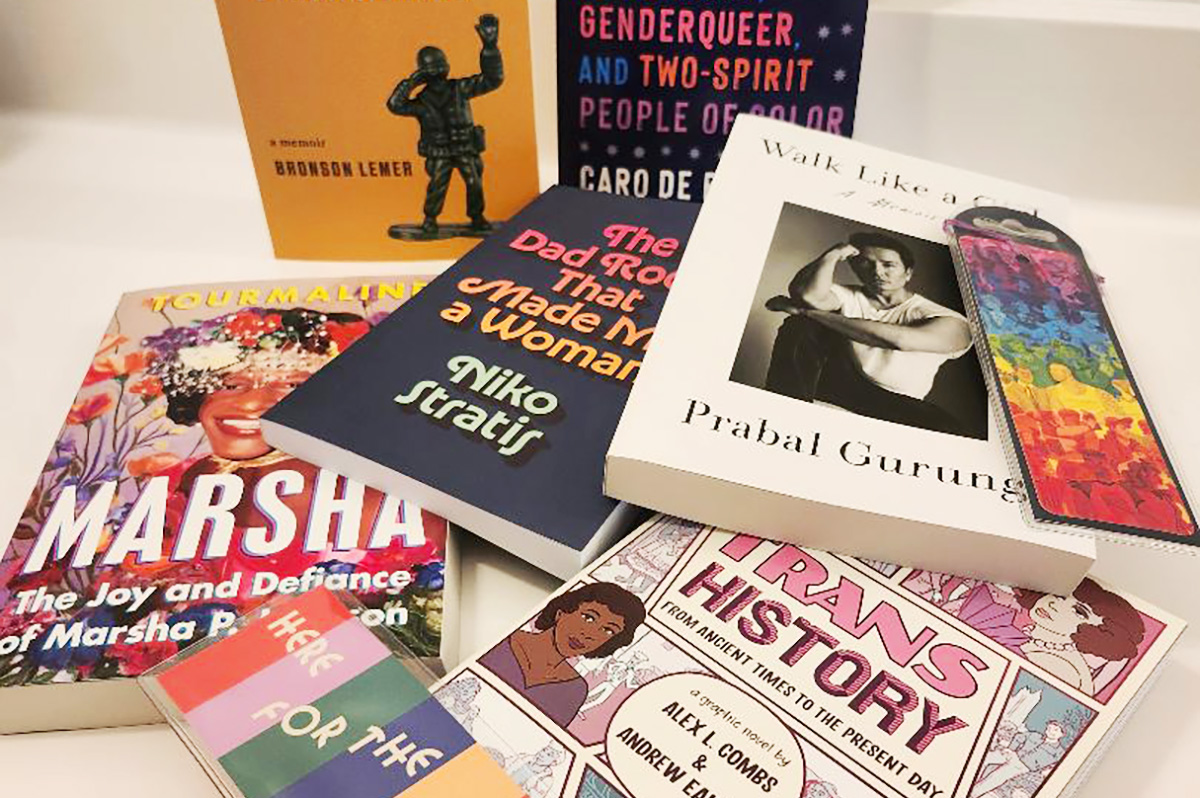

Marching in parades, dancing in the streets, standing up for people in your community. But you’re also likely to have some time to rest and reflect – and with these great new books, to read.

First, dip into a biography with “Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson” by Tourmaline (Tiny Rep Books, $30), a nice look at an icon who, rumor has it, threw the brick that started a revolution. It’s a lively tale about Marsha P. Johnson, her life, her activism before Stonewall and afterward. Reading this interesting and highly researched history is a great way to spend some time during Pride month.

For the reader who can’t live without music, try “The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman” by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press, $27.95), the story of being trans, searching for your place in the world, and finding it in a certain comfortable genre of music. Also look for “The Lonely Veteran’s Guide to Companionship” by Bronson Lemer (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95), a collection of essays that make up a memoir of this and that, of being queer, basic training, teaching overseas, influential books, and life.

If you still have room for one more memoir, try “Walk Like a Girl” by Prabal Gurung (Viking, $32.00). It’s the story of one queer boy’s childhood in India and Nepal, and the intolerance he experienced as a child, which caused him to dream of New York and the life he imagined there. As you can imagine, dreams and reality collided but nonetheless, Gurung stayed, persevered, and eventually became an award-winning fashion designer, highly sought by fashion icons and lovers of haute couture. This is an inspiring tale that you shouldn’t miss.

No Pride celebration is complete without a history book or two.

In “Trans History: From Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Alex L. Combs & Andrew Eakett ($24.99, Candlewick Press), you’ll see that being trans is something that’s as old as humanity. One nice part about this book: it’s in graphic novel form, so it’s lighter to read but still informative. Lastly, try “So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color” by Caro De Robertis (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $32.00) a collection of thoughts, observations, and truths from over a dozen people who share their stories. As an “oral history,” you’ll be glad to know that each page is full of mini-segments you can dip into anywhere, read from cover to cover, double-back and read again. It’s that kind of book.

And if these six books aren’t enough, if they don’t quite fit what you crave now, be sure to ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for help. There are literally tens of thousands of books that are perfect for Pride month and beyond. They’ll be able to determine what you’re looking for, and they’ll put it directly in your hands. So stand up. March. And then sit and read.

-

Federal Government2 days ago

Federal Government2 days agoTreasury Department has a gay secretary but LGBTQ staff are under siege

-

Virginia3 days ago

Virginia3 days agoDefying trends, new LGBTQ center opens in rural Winchester, Va.

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoGay GOP group hosts Ernst, 3 House members — all of whom oppose Equality Act

-

Opinions4 days ago

Opinions4 days agoUSAID’s demise: America’s global betrayal of trust with LGBTQ people