Movies

Miyazaki caps career with masterful ‘Boy and the Heron’

A treatise on the need for harmony between man and nature

If anyone can be said to rival the impact of Walt Disney on the field of animated films, it’s Hayao Miyazaki. Co-founder of Studio Ghibli, his work in Japan’s anime genre is legendary, with films like “My Neighbor Totoro,” “Kiki’s Delivery Service,” “Howl’s Moving Castle,” and the Oscar-winning “Spirited Away” – which held the record as the highest-grossing film in Japanese history for 19 years – expanding his popularity and helping to build a global entertainment empire that, like Disney’s, includes merchandise, licensing, and even a theme park.

Millions of fans worldwide – many of them queer – have grown up loving his movies not just for their unique blend of the fanciful, the poignant, and the profound but for the sublime visual artistry and masterful storytelling with which they are rendered.

Now 83, the revered animator announced his retirement from making feature films in 2013 – only to start work, three years later, on another one. Seven years afterward, that project reached fruition with “The Boy and the Heron,” released in its native Japan last summer. And if any proof is needed to stand as testament to Miyazaki’s popularity, it can be found in the fact that, in spite of a deliberately minimal promotion strategy (the film was released with no teasers, trailers, or fanfare besides a single poster image), it had the biggest opening weekend of any Studio Ghibli film to date, going on to become the first original anime film (and the first film by Miyazaki) to achieve number one status at the box office in both Canada and the U.S.

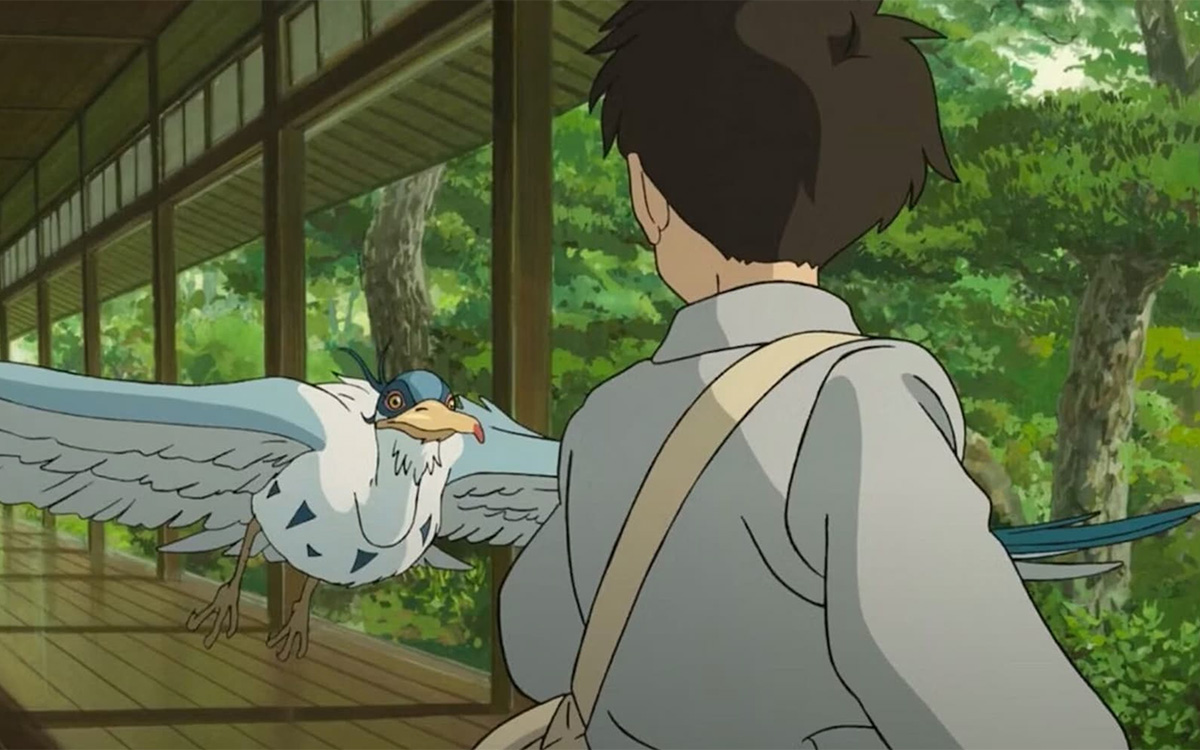

Initially released in the latter country on Dec. 8, and still in theaters in the wake of its Golden Globe win and Oscar nomination as Best Animated Film of 2023, “Heron” – written and directed by Miyazaki and inspired by (though otherwise unrelated to) Genzaburō Yoshino’s 1937 novel “How Do You Live?” – is an autobiographically leaning story centered on young Mahito (Soma Santoki / Luca Padovan in the English dubbed version), a boy growing up in Tokyo during World War II. Following the death of his mother in a hospital fire, his industrialist father (Takuya Kimura / Christian Bale) soon remarries, with his late wife’s younger sister (Yoshino Kimura / Gemma Chan) as his new bride, and Mahito finds himself living at her family’s estate in the rural countryside. There, a mysterious – and persistent – heron (Masaki Suda / Robert Pattinson) seems to take interest in him, and he begins to feel taunted by its attentions – but when his new stepmother disappears into the surrounding forest, the bird leads him into an overgrown tower, where a seemingly all-powerful lord (Shōhei Hino / Mark Hamill) rules over a hidden underworld, and he embarks on an epic quest through its mystical landscape to rescue her, helped along the way by a swashbuckling fisherwoman (Ko Shibasaki / Florence Pugh) and a guardian fire spirit (Aimyon / Karen Fukuhara) – discovering the secrets of a magical family history stretching back across generations as he goes.

Considering its unmistakable parallels to Miyazaki’s real-life childhood (his father, like Mahito’s, was an industrialist working for a company that manufactured war planes, allowing him an affluent and somewhat sheltered upbringing in a devastated Japan), it’s impossible not to see his latest movie as a “swan song.” Indeed, it was widely branded as such by journalists ahead of its release, and the director himself declared it his “last,” though that has since been recanted by Studio Ghibli with the announcement that he is working on another. Still, while it may not be his final manifesto, it would certainly be a worthy one.

Infused with the filmmaker’s signature recurring themes – the need for harmony between man and nature, the paradoxical absurdities of technology, the value of traditional lifestyles and the importance of craft and artistry, the conflict between pacifist ideals and violence that dominates human affairs – and weaving a mythic tale that postulates a deeper reality where life and death are forever intertwined in a realm of impermanent permanence, “Heron” feels as much like a statement of belief as it does a fantasy. One might even sense that there’s an insistence that it can be both, and that life itself is a sort of fantasy, capable of being shaped by things that exist only within our imaginations, and that, of course, is the source of its power.

Such cosmic speculations aside, however, Miyazaki’s movie hooks us not with its esoteric metaphysics, but with its meditations on loss, grief, and the challenge of finding peace in a world that often seems dominated by chaos and indiscriminate destruction. Artfully framed to suggest that the “fantasy” elements of its plot either might or might not exist only within its youthful protagonist’s delirious, wounded mind, it touches us to the heart with the harsh realities of Mahito’s young life; the opening sequence, depicting the fire that kills his mother, is horrific, leaving its shadow on the rest of the film even as it does on Mahito’s soul, and his grief, compounded and left unreconciled by his loving-but-ham-handed father’s seeming refusal to address or even acknowledge it, resonates on a universal wavelength simply because it is so fundamentally human. It’s in grappling with these elements of life – the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” to which Shakespeare refers in “Hamlet,” a play which is, perhaps not coincidentally, echoed in an inverted form within the structure of Miyazaki’s narrative – that the movie brings a sense of truth to the magical realism it embraces. The comforts it offers do not feel like hollow platitudes; rather, they point us toward wisdom, much in the way of a riddle told by a Zen Master, and a way of looking at the world that is comfort enough in itself.

Yet “The Boy and the Heron” is not made of the kind of late-career introspection that robs it of its sense of fun. Full of adventure, action, and the filmmaker’s signature blend of gorgeously animated realism with adorable absurdity inspired by Kawaii (Japanese “cute culture”), it offers as much spirited adventure and comedic flair as expected from a Miyazaki film– and it’s populated with just as many whimsically grotesque creatures and characters, to boot.

Needless to say, perhaps, it’s also a stunning film to behold, evoking a classic Japanese woodcut brought to life and infused with a powerful spirit of its own; though enhanced and aided by modern technology, the animation – as with all of Miyazaki’s work – is hand-drawn, making its visual perfection even more breathtaking. Add to all this the beautiful score by longtime friend and collaborator Joe Hisaishi, and the result is irresistible.

Given that “The Boy in the Heron” is likely a top contender for the win at this year’s Oscars, it’s likely to be accessible on the big screen – in some markets, at least – for a while before it becomes available for streaming. Whether or not you can see it now, keep it on your radar – we don’t use the word “masterpiece” lightly, but we suggest this one might qualify, and you owe it to yourself to watch it so that you can decide for yourself.

We’re pretty sure you’ll agree.

Movies

‘Housekeeping for Beginners’ embraces true meaning of family

Another triumph from young filmmaker Goran Stolevski

Once upon a time in America, queer people sometimes adopted their lovers as their “children” so that they could be legally bound together as family.

That’s not a revelation, though some queer younglings may be shocked to learn this particular nugget of hidden history, nor is it a call to political awareness in an election year when millions are actively working to roll back our freedoms. We bring it up merely as a sort of context for the world that provides the setting in “Housekeeping for Beginners,” the winner of the Queer Lion prize at 2023’s Venice Film Festival, which opened in limited U.S. theaters on April 5 and expanded for a wider release last weekend.

Written and directed by Goran Stolevski – a Macedonian-born Australian filmmaker whose two previous films, “You Won’t Be Alone” and “Of An Age,” both released in 2022, each met with critical acclaim – and submitted (unsuccessfully) as the official Oscar entry for International Feature from the Republic of North Macedonia, it’s a movie about what it means to be “family,” which touches on the political while placing its focus on the personal – in other words, on lived experience rather than ideological argument – and, in the process, drives home some very important existential warnings at a time when things could go either way.

Set in the North Macedonian capital of Skopje, it centers on social worker Dita (Anamaria Marinca), a middle-aged lesbian, whose house is a safe haven for a collection of outcasts. First and foremost is her girlfriend Suada (Alina Serban), a single mother of Romani heritage, but the “chosen family” in the household also includes Suada’s daughters, teenaged Vanesa (Mia Mustafi) and precocious 5-year-old Mia (Dżada Selim); Dita’s long-term friend Toni (Vladimir Tintor), a middle-aged gay man who works night shifts at a mental hospital; Toni’s new, much-younger boyfriend Ali (Samson Selim); and Elena (Sara Klimoska), an older and more worldly schoolmate of the other girls who serves as a makeshift big sister.

It is, unsurprisingly, a chaotic environment, a sea of revolving situations that largely goes on without Dita’s direct involvement, though she occasionally asserts more authority than she either has or cares to wield. That all changes, however, when Suada is diagnosed with aggressive pancreatic cancer, leading her to extract from her lover the promise that she will be mother to her children when she’s gone.

If you want a spoiler-free experience, you should stop reading now; further discussion of “Housekeeping for Beginners” requires us to reveal that Dita is forced to make good on that promise, even though she’s never had the desire to be a mother, and it’s not just a matter of making sure the kids get all their daily meals and show up for school on time. In North Macedonia, where same-sex relationships are not illegal but are neither granted the validation of lawful protections, the adoption of children requires a woman to have a husband, which means entering into a sham marriage with Toni – who is not quite a 100% onboard, himself – and listing him as the girls’ father. More difficult, perhaps, is gaining the trust of Suada’s two daughters, neither of whom is exactly receptive to the prospect of exchanging their real mother for a half-willing replacement. It’s this challenge that proves most daunting, triggering a crisis that will put every member of this cobbled-together family group to the test if they are to have any hope of hanging on to each other and making it work – something to which Dita finds herself growing deeply committed, despite her initial reticence about taking on the role of default matriarch.

Shot in Stolevski’s accustomed milieu – an intimate, cinema verité style built on handheld camerawork and near-exclusive reliance on close-up framing to capture the awkward blend of comfort and claustrophobia that often accompanies life in a crowded household environment – and leaving most of the expository cultural details, such as the impact of ethnic “caste” and the complicated hierarchy of layers involved in negotiating a peaceful coexistence with “normal” Macedonian society when your domestic and familial structures are anything but “normal”, to be gleaned by context rather than direct explanation. It works, of course; there’s something universally recognizable about the difficulty of “blending in” that helps us bridge the gap even if we don’t quite understand all the fine points as well as we might if we, like Stolevski, had grown up having to deal with them directly.

Even so, there are times when a bit of distance might be missed by audiences in need of a wider scope; it’s hard, after all, to get a palpable sense of space and location when most of what we see onscreen are the upper thirds of whichever cast members happen to be featured in each particular scene. But in case that sounds like a criticism, it’s important to point out that this is part of the film’s magic spell – because by making its physical environment essentially synonymous with its emotional one, Stolevski’s movie delivers its human truth without the unnecessary distraction of learning the ins and outs of a foreign cultural dynamic. The things we need to grasp, we do, without question, even if we don’t quite understand the full context, and what we walk away with in the end is a universally recognizable sense of family, carved in stark relief among a group of people who find it among themselves despite the lack of blood ties or common history to bind them to each other. That makes “Household for Beginners” an unequivocal triumph in one way, at least, because by driving home that hard-to-convey understanding, it manages to underscore the injustice and inhumanity of any world in which the validity of a family is subject to the judgment of cultural bias.

That’s not to say that “Housekeeping” is an unrelenting downer of political messaging. On the contrary, it is lifted by a clear imperative to show the joys of being part of such a family; the humor, the snark, the bright spots that arise even in the darkest moments – all these are amply and aptly portrayed, making sure that we never feel like we are being fed a doom-and-gloom scenario. Rather, we’re being reminded that it’s the visceral happiness that comes from being connected with those we love that matters far more than the rules and judgments of outsiders, which makes the hoops Dita and company have to jump through feel all the more absurd.

Though Stolevski, an Aussie citizen unspooling a narrative based in his country of origin, might not have intended it as such, the message of his film strikes a particular chord in 2024 America. The hardships of Dita and her brood as they try to simply stay together are a clear and pointed warning not to take for granted the hard-won freedoms that we have.

Add to that a superb collection of performances (BAFTA-winner Marinca and first-time actor Selim are standouts among the many), and you have another triumph from a young filmmaker whose reputation only gets more stellar with each effort.

Movies

After 25 years, a forgotten queer classic reemerges in 4K glory

Screwball rom-com ‘I Think I Do’ finds new appreciation

In 2024, with queer-themed entertainment available on demand via any number of streaming services, it’s sometimes easy to forget that such content was once very hard to find.

It wasn’t all that long ago, really. Even in the post-Stonewall ‘70s and ‘80s, movies or shows – especially those in the mainstream – that dared to feature queer characters, much less tell their stories, were branded from the outset as “controversial.” It has been a difficult, winding road to bring on-screen queer storytelling into the light of day – despite the outrage and protest from bigots that, depressingly, still continues to rear its ugly head against any effort to normalize queer existence in the wider culture.

There’s still a long way to go, of course, but it’s important to acknowledge how far we’ve come – and to recognize the efforts of those who have fought against the tide to pave the way. After all, progress doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and if not for the queer artists who have hustled to bring their projects to fruition over the years, we would still be getting queer-coded characters as comedy relief or tragic victims from an industry bent on protecting its bottom line by playing to the middle, instead of the (mostly) authentic queer-friendly narratives that grace our screens today.

The list of such queer storytellers includes names that have become familiar over the years, pioneers of the “Queer New Wave” of the ‘90s like Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, Gregg Araki, or Bruce LaBruce, whose work at various levels of the indie and “underground” queer cinema movement attracted enough attention – and, inevitably, notoriety – to make them known, at least by reputation, to most audiences within the community today.

But for every “Poison” or “The Living End” or “Hustler White,” there are dozens of other not-so-well-remembered queer films from the era; mostly screened at LGBTQ film festivals like LA’s Outfest or San Francisco’s Frameline, they might have experienced a flurry of interest and the occasional accolade, or even a brief commercial release on a handful of screens, before slipping away into fading memory. In the days before streaming, the options were limited for such titles; home video distribution was a costly proposition, especially when there was no guarantee of a built-in audience, so most of them disappeared into a kind of cinematic limbo – from which, thankfully, they are beginning to be rediscovered.

Consider, for instance, “I Think I Do,” the 1998 screwball romantic comedy by writer/director Brian Sloan that was screened last week – in a newly restored 4K print undertaken by Strand Releasing – in Brooklyn as the Closing Night Selection of NewFest’s “Queering the Canon” series. It’s a film that features the late trans actor and activist Alexis Arquette in a starring, pre-transition role, as well as now-mature gay heartthrob Tuc Watkins and out queer actor Guillermo Diaz in supporting turns, but for over two decades has been considered as little more than a footnote in the filmographies of these and the other performers in its ensemble cast. It deserves to be seen as much more than that, and thanks to a resurgence of interest in the queer cinema renaissance from younger film buffs in the community, it’s finally getting that chance.

Set among a circle of friends and classmates at Washington, D.C.’s George Washington University, it’s a comedic – yet heartfelt and nuanced – story of love left unrequited and unresolved between two roommates, openly gay Bob (Arquette) and seemingly straight Brendan (Christian Maelen), whose relationship in college comes to an ugly and humiliating end at a Valentine’s Day party before graduation. A few years later, the gang is reunited for the wedding of Carol (Luna Lauren Vélez) and Matt (Jamie Harrold), who have been a couple since the old days. Bob, now a TV writer engaged to a handsome soap opera star (Watkins), is the “maid” of honor, while old gal pals Beth (Maddie Corman) and Sarah (Marianne Hagan), show up to fill out the bridal party and pursue their own romantic interests. When another old friend, Eric (Diaz), shows up with Brendan unexpectedly in tow, it sparks a behind-the-scenes scenario for the events of the wedding, in which Bob is once again thrust into his old crush’s orbit and confronted with lingering feelings that might put his current romance into question – especially since the years between appear to have led Brendan to a new understanding about his own sexuality.

In many ways, it’s a film with the unmistakable stamp of its time and provenance, a low-budget affair shot at least partly under borderline “guerilla filmmaking” conditions and marked by a certain “collegiate” sensibility that results in more than a few instances of aggressively clever dialogue and a storytelling agenda that is perhaps a bit too heavily packed. Yet at the same time, these rough edges give it a raw, DIY quality that not only makes any perceived sloppiness forgivable, but provides a kind of “outsider” vibe that it wears like a badge of honor. Add to this a collection of likable performances – including Arquette, in a winning turn that gets us easily invested in the story, and Maelen, whose DeNiro-ish looks and barely concealed sensitivity make him swoon-worthy while cementing the palpable chemistry between them – and Sloan’s 25-year-old blend of classic Hollywood rom-com and raunchy ‘90s sex farce reveals itself to be a charming, wiser-than-expected piece of entertainment, with an admirable amount of compassion and empathy for even its most stereotypical characters – like Watkins’ soap star, a walking trope of vainglorious celebrity made more fully human than appearances would suggest by the actor’s honest, emotionally intelligent performance – that leaves no doubt its heart is in the right place.

Sloan, remarking about it today, confirms that his intention was always to make a movie that was more than just frothy fluff. “While the film seems like a glossy rom-com, I always intended an underlying message about the gay couple being seen as equals to the straight couple getting married,” he says. “ And the movie is also set in Washington to underline the point.”

He also feels a sense of gratitude for what he calls an “increased interest from millennials and Gen Z in these [classic queer indie] films, many of which they are surprised to hear about from that time, especially the comedies.” Indeed, it was a pair of clips from “his film”I Think I Do” featured on Queer Cinema Archive that “garnered a lot of interest from their followers,” and “helped to convince my distributor to bring the film back” after being unavailable for almost 10 years.

Mostly, however, he says “I feel very lucky that I got to make this film at that time and be a part of that movement, which signaled a sea change in the way LGBTQ characters were portrayed on screen.”

Now, thanks to Strand’s new 4K restoration, which will be available for VOD streaming on Amazon and Apple starting April 19, his film is about to be accessible to perhaps a larger audience than ever before.

Hopefully, it will open the door for the reappearance of other iconic-but-obscure classics of its era and help make it possible for a whole new generation to discover them.

Movies

Trans filmmaker queers comic book genre with ‘People’s Joker’

Alternative ‘Batman’ universe a medium for mythologized autobiography

It might come as a shock to some comic book fans, but the idea of super heroes and super villains has always been very queer. Think about it: the dramatic skin-tight costumes, the dual identities and secret lives, the inability to fit in or connect because you are distanced from the “normal” world by your powers – all the standard tropes that define this genre of pop culture myth-making are so rich with obviously queer-coded subtext that it seems ludicrous to think anyone could miss it.

This is not to claim that all superhero stories are really parables about being queer, but, if we’re being honest some of them feel more like it than others; an obvious example is “Batman,” whose domestic life with a teenage boy as his “ward” and close companion has been raising eyebrows since 1940. The campy 1960s TV series did nothing to distance the character from such associations – probably the opposite, in fact – and Warner Brothers’ popular ‘80s-’90s series of film adaptations solidified them even more by ending with gay filmmaker Joel Schumacher’s much-maligned “Batman and Robin,” starring George Clooney and Chris O’Donnell in costumes that highlighted their nipples, which is arguably still the queerest superhero movie ever made.

Or at least it was. That title might now have to be transferred to “The People’s Joker,” which – as it emphatically and repeatedly reminds us – is a parody in no way affiliated with DC’s iconic “Batman” franchise or any of its characters, even though writer, director and star Vera Drew begins it with a dedication to “Mom and Joel Schumacher.” Parody it may be, but that doesn’t keep it from also serving up lots of food for serious thought to chew on between the laughs.

Set in a sort of comics-inspired dystopian meta-America where unsanctioned comedy is illegal, it’s the story of a young, closeted transgender comic (Drew) who leaves her small town home to travel to Gotham City and audition for “GCB” – the official government-produced sketch comedy show. Unfortunately, she’s not a very good comic, and after a rocky start she decides to leave to form a new comedy troupe (labeled “anti-comedy” to skirt legality issues) along with penguin-ish new friend Oswald Cobblepot (Nathan Faustyn). They collect an assortment of misfit would-be comedians to join them, and after branding herself as “Joker the Harlequin,” our protagonist starts to find her groove – but it will take negotiating a relationship with trans “bad boy” Mr. J (Kane Distler), a confrontation with her self-absorbed and transphobic mother (Lynn Downey), and making a choice between playing by the rules or breaking them before she can fully transition into the militant comic activist she was always meant to be.

Told as a wildly whimsical, mixed media narrative that combines live action with a quirky CGI production design and multiple styles of animation (with different animators for each sequence), “People’s Joker” is by no means the kind of big-budget blockbuster we expect from a movie about a superhero — or in this case, supervillain, though the topsy-turvy context of the story more or less reverses that distinction — but it should be obvious from the synopsis above that’s not what Drew was going for, anyway. Instead, the Emmy-nominated former editor uses her loopy vision of an alternative “Batman” universe as the medium for a kind of mythologized autobiography expressing her own real-life journey, both toward embracing her trans identity and forging a maverick career path in an industry that discourages nonconformity, while also spoofing the absurdities of modern culture. Subverting familiar tropes, yet skillfully weaving together multiple threads from the “real” DC Universe she’s appropriated with the detailed savvy of a die-hard fangirl, it’s an accomplishment likely to impress her fellow comic book fans — even if they can’t quite get behind the gender politics or her presentation of Batman himself (an animated version voiced by Phil Braun) as a closeted gay right-wing demagogue and serial sexual abuser.

These elements, of course, are meant to be deliberately provocative. Drew, like her screen alter ego, is a confrontation comic at heart, bent on shaking up the dominant paradigm at every opportunity. Yet although she takes aim at the expected targets – the patriarchy, toxic masculinity, corporate hypocrisy, etc. – she is equally adept at scoring hits against things like draconian ideals of political correctness and weaponized “cancel culture”, which are deployed with extreme prejudice from idealogues on both sides of the ideological divide. This means she might be risking the alienation of an audience which might otherwise be fully in her corner – but it also provides the ring of unbiased personal truth that keeps the movie from sliding into propaganda and elevates it, like “Barbie”, to the level of absurdist allegory.

Because ultimately, of course, the point of “People’s Joker” has little to do with the politics and social constructs it skewers along the way; at its core, it’s about the real human things that resonate with all of us, regardless of gender, sexuality, ideology, or even political parties: the need to feel loved, to feel supported, and most of all, to be fully actualized. That means the real heart of the film beats in the central thread of its troubled connection between mother and daughter, superbly rendered in both Drew and Downey’s performances, and it’s there that Joker is finally able to break free of her own self-imposed restrictions and simply “be” who she is.

Other performances deserve mention, too, such as Faustyn’s weirdly lovable “Penguin” stand-in and Outsider multi-hyphenate artist David Leibe Hart as Ra’s al Ghul – a seminal “Batman” villain here reimagined as a veteran comic that serves as a kind of Obi-Wan Kenobi figure in Joker’s quest. In the end, though, it’s Drew’s show from top to bottom, a showcase for not only her acting skills, which are enhanced by the obvious intelligence (including the emotional kind) she brings to the table, but her considerable talents as a writer, director, and editor.

For some viewers, admittedly, the low-budget vibe of this crowd-funded film might create an obstacle to appreciating the cleverness and artistic vision behind it, though Drew leans into the limitations to find remarkably creative ways to convey what she wants with the means she has at her disposal. Others, obviously, will have bigger problems with it than that. Indeed, the film, which debuted at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, was withdrawn from competition there and pulled from additional festival screenings after alleged corporate bullying (presumably from Warner Brothers, which owns the film rights to the Batman franchise) pressured Drew into holding it back. Clearly, concern over blowback from conservative fans – who would likely never see the film anyway – was enough to warrant strong arm techniques from nervous execs. Nevertheless, “The People’s Joker” made its first American appearance at LA’s Outfest in 2023, and is now receiving a rollout theatrical release that started on April 5 in New York, and continues this week in Los Angeles, with Washington DC and other cities to follow on April 12 and beyond.

If you’re in one of the places where it plays, we say it’s more than worth making the effort. If you’re not, never fear. A VOD/streaming release is sure to come soon.

-

District of Columbia3 days ago

District of Columbia3 days agoCatching up with the asexuals and aromantics of D.C.

-

State Department5 days ago

State Department5 days agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

South America3 days ago

South America3 days agoArgentina government dismisses transgender public sector employees

-

Maine4 days ago

Maine4 days agoMaine governor signs transgender, abortion sanctuary bill into law