Theater

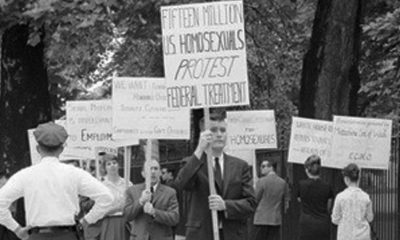

‘217 Boxes’ play recalls pivotal moment in LGBT rights

Dr. Henry Anonymous made memorable appearance at 1972 panel discussion

Derek Luci in ‘217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous.’ (Photo by Paula Court)

‘217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous’

Baryshnikov Arts Center, Jerome Robbins Theater

450 West 37th St., New York

7:30 p.m. nightly through May 11

John Fryer is not a household name, though he’s considered among the five most impactful activists for LGBT civil rights and is directly at the center of one of the biggest civil rights events in the U.S.

Under the guise of Dr. Henry Anonymous, the psychiatrist masqueraded himself in a mask and through a voice modulator appeared on a homosexuality panel with late gay rights pioneers Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings at the 1972 American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting, which helped to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder.

The events of what transpired are showcased in the new play “217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous,” written by Ain Gordon. Equality Forum is presenting the show at the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York City through May 11.

“John Fryer first came on my radar about 20 years ago, but at that point, I don’t know if I fully understood his impact,” says Malcolm Lazin, executive director of the Equality Forum. “Roughly two years ago, Ain Gordon was commissioned by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania to do a play about a figure who went unrecognized and as it turns out, that’s where the 217 boxes of John Fryer’s archives are stored.”

The playwright learned of Fryer’s story during a two-year residency at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania while he was searching for incidents about personal battles for public liberty, and specifically wanted to find something LGBT-related. He knew immediately this story was what he was looking for.

The Equality Forum was impressed with the play and decided it was something it wanted to stage it as part of the Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting, which is being held this week in New York City as well, as it’s the 45th anniversary of the declassification. Current medical director Saul Levin is the first openly gay man to head the Association.

“The reviews speak for themselves, but it’s a remarkable play about a period of time, and what’s interesting to me is that it’s also being presented in the same month that ‘Boys in the Band’ is being performed, as they are both in the same time period,” Lazin says. “One is about the impact of internal homophobia and the other is about the conditions that existed and the heroism of John Fryer in stepping forward and creating a tremendous change.”

The play is about who Fryer was and it’s answered through three different characters the playwright found in the 217 boxes.

“Ain, who happens to be a gay man, had not previously done a play around gay subject matter. He’s known for his monologues and what he decided to do was go through those 217 boxes he found to inform him who John Fryer really was,” Lazin says. “The first of the characters was Alfred Gross (played by Derek Lucci), an early Civil Rights activist, who helped gay men who had problems with the law. He interfaced with John because very few psychiatrists would come into a court of law to discuss these things.”

The second person introduced in the play is Katherine M. Luder (played by Laura Esterman), Fryer’s secretary, a spinster who worked for him from age 67-91.

“One of the remarkable things you learn from her is that John was likely one of the very first psychiatrists in the country to provide psychological counseling for HIV patients who were bereaved,” Lazin says.

The third character is Fryer’s father, Ercel (played by Ken Marks), and he’s there to explain his son’s upbringing and what led to him delivering this memorable speech. It’s learned Fryer was raised in rural Kentucky, became a graduate of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and was discharged from its residency in psychiatry when the truth about his homosexuality came out.

Learning about this man, Lazin notes, is wildly important for the future and he’s happy the play is doing so well.

“If we want to build a sustainable bridge to the future, we need to build a bridge empowered by our past, and we have that past, but we’re just not telling it,” Lazin says. “This is an opportunity to learn about that past.”

Theater

‘Octet’ explores the depths of digital addiction

Habits not easily shaken in Studio Theatre chamber musical

‘Octet’

Through Feb. 26

Studio Theatre

1501 14th Street, N.W.

Tickets start at $55

Studiotheatre.org

David Malloy’s “Octet” delves deep into the depths of digital addiction.

Featuring a person ensemble, this extraordinary a capella chamber musical explores the lives of recovering internet addicts whose lives have been devastated by digital dependency; sharing what’s happened and how things have changed.

Dressed in casual street clothes, the “Friends of Saul” trickle into a church all-purpose room, check their cell phones in a basket, put away the bingo tables, and arrange folding chairs into a circle. Some may stop by a side table offering cookies, tea, and coffee before taking a seat.

The show opens with “The Forest,” a haunting hymn harking back to the good old days of an analog existence before glowing screens, incessant pings and texts.

“The forest was beautiful/ My head was clean and clear/Alone without fear/ The forest was safe/ I danced like a beautiful fool / One time some time.”

Mimicking an actual step meeting, there’s a preamble. And then the honest sharing begins, complete with accounts of sober time and slips.

Eager to share, Jessica (Chelsea Williams) painfully recalls being cancelled after the video of her public meltdown went viral. Henry (Angelo Harrington II) is a gay gamer with a Candy Crush problem. Toby (Adrian Joyce) a nihilist who needs to stay off the internet sings “So anyway/ I’m doing good/ Mostly/ Limiting my time/ Mostly.”

The group’s unseen founder Saul is absent, per usual.

In his stead Paula, a welcoming woman played with quiet compassion by Tracy Lynn Olivera, leads. She and her husband no longer connect. They bring screens to bed. In a love-lost ballad, she explains: “We don’t sleep well/ My husband I/ Our circadian rhythms corrupted/ By the sallow blue glow of a screen/ Sucking souls and melatonin/ All of my dreams have been stolen.”

After too much time spent arguing with strangers on the internet, Marvin, a brainy young father played by David Toshiro Crane, encounters the voice of a God.

Ed (Jimmy Kieffer) deals with a porn addiction. Karly (Ana Marcu) avoids dating apps, a compulsion compared to her mother’s addiction to slot machines.

Malloy, who not only wrote the music but also the smart lyrics, book, and inventive vocal arrangements, brilliantly joins isolation with live harmony. It’s really something.

And helmed by David Muse, “Octet” is a precisely, quietly, yet powerfully staged production, featuring a topnotch cast who (when not taking their moment in the spotlight) use their voices to make sounds and act as a sort of Greek chorus. Mostly on stage throughout all of the 100-minute one act, they demonstrate impressive stamina and concentration.

An immersive production, “Octet” invites audience members to feel a part of the meeting. Studio’s Shargai Theatre is configured, for the first, in the round. And like the characters, patrons must also unplug. Everyone is required to have their phones locked in a small pouch (that only ushers are able to open and close), so be prepared for a wee bit of separation anxiety.

At the end of the meeting, the group surrenders somnambulantly. They know they are powerless against internet addiction. But group newbie Velma (Amelia Aguilar) isn’t entirely convinced. She remembers the good tech times.

In a bittersweet moment, she shares of an online friendship with “a girl in Sainte Marie / Just like me.”

Habits aren’t easily shaken.

Theater

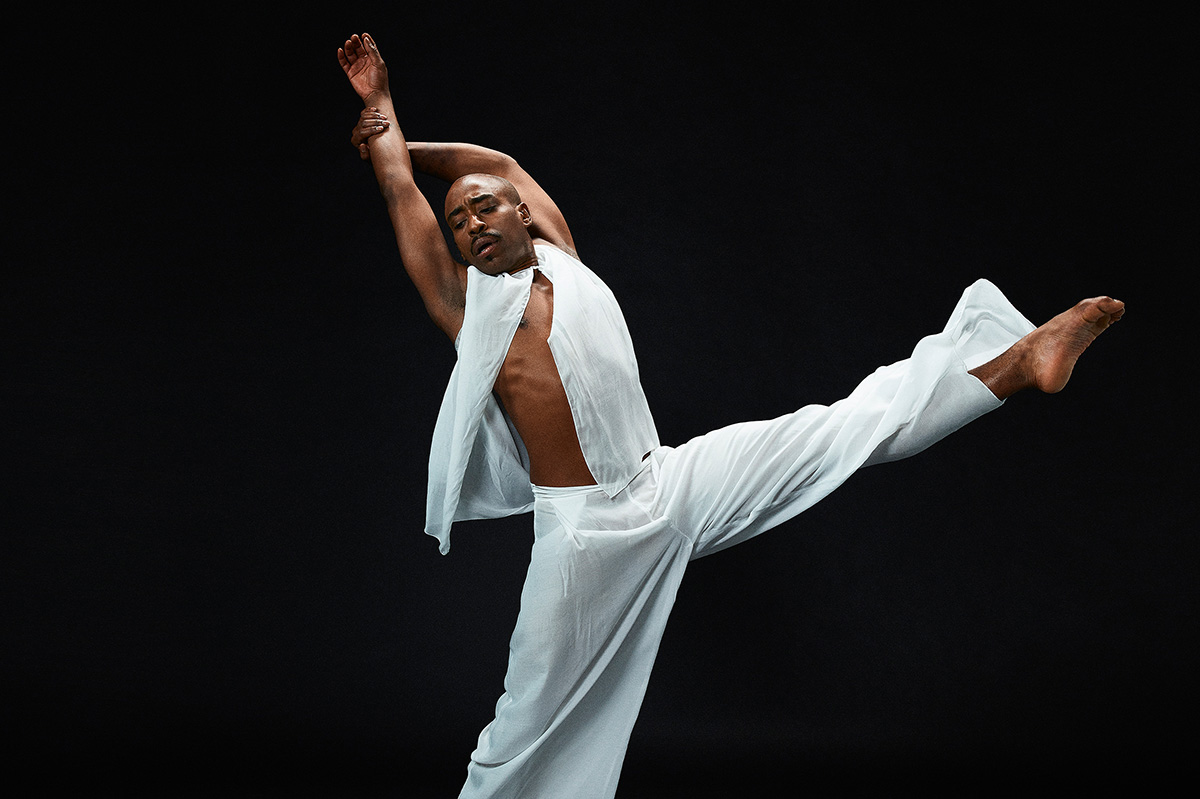

Out dancer on Alvin Ailey’s stint at Warner Theatre

10-day production marks kickoff of national tour

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Through Feb. 8

Warner Theatre

513 12th St., N.W.

Tickets start at $75

ailey.org

The legendary Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is coming to Washington’s Warner Theatre, and one of its principal veterans couldn’t be more pleased. Out dancer Renaldo Maurice is eager to be a part of the company’s 10-day stint, the kickoff of a national tour that extends through early May.

“I love the respectful D.C. crowd and they love us,” says Maurice, a member of esteemed modern dance company for 15 years. The traveling tour is made of two programs and different casting with Ailey’s masterwork “Revelations” in both programs.

Recently, we caught up with Maurice via phone. He called from one of the quiet rooms in his New York City gym where he’s getting his body ready for the long Ailey tour.

Based in North Newark, N.J., where he recently bought a house, Maurice looks forward to being on the road: “I enjoy the rigorous performance schedule, classes, shows, gym, and travel. It’s all part of carving out a lane for myself and my future and what that looks like.”

Raised by a single mother of three in Gary, Ind., Maurice, 33, first saw Alvin Ailey as a young kid in the Auditorium Theatre in downtown Chicago, the same venue where he’s performed with the company as a professional dancer.

He credits his mother with his success: “She’s a real dance mom. I would not be the man or artist I am today if it weren’t for the grooming and discipline of my mom. Support and encouragement. It’s impacted my artistry and my adulthood.”

Maurice is also part of the New York Ballroom scene, an African-American and Latin underground LGBTQ+ subculture where ball attendees “walk” in a variety of categories (like “realness,” “fashion,” and “sex siren”) for big prizes. He’s known as the Legendary Overall Father of the Haus of Alpha Omega.

WASHINGTON BLADE: Like many gay men of his era, Ailey lived a largely closeted public life before his death from AIDS-related complications in 1989.

RENALDO MAURICE Not unusual for a Black gay man born during the Depression in Rogers, Texas, who’s striving to break out in the industry to be a creative. You want to be respected and heard. Black man, and Black man who dances, and you may be same-sex gender loving too. It was a lot, especially at that time.

BLADE: Ailey has been described as intellectual, humble, and graceful. He possessed strength. He knew who he was and what stories he wanted to tell.

MAURICE: Definitely, he wanted to concentrate on sharing and telling stories. What kept him going was his art. Ailey wanted dancers to live their lives and express that experience on stage. That way people in the audience could connect with them. It’s incredibly powerful that you can touch people by moving your body.

That’s partly what’s so special about “Revelations,” his longest running ballet and a fan favorite that’s part of the upcoming tour. Choreographed by Alvin Ailey in 1960, it’s a modern dance work that honors African-American cultural heritage through themes of grief, joy, and faith.

BLADE: Is “Revelation” a meaningful piece for you?

MAURICE: It’s my favorite piece. I saw it as a kid and now perform it as a professional dance artist. I’ve grown into the role since I was 20 years old.

BLADE: How can a dancer in a prestigious company also be a ballroom house father?

MAURICE: I’ve made it work. I learned how to navigate and separate. I’m a principal dancer with Ailey. And I take that seriously. But I’m also a house father and I take that seriously as well.

I’m about positivity, unity, and hard work. In ballroom you compete and if you’re not good, you can get chopped. You got to work on your craft and come back harder. It’s the same with dance.

BLADE: Any message for queer audiences?

MAURICE: I know my queer brothers and sisters love to leave with something good. If you come to any Ailey performance you’ll be touched, your spirit will be uplifted. There’s laughter, thoughtful and tender moments. And it’s all delivered by artists who are passionate about what they do.

BLADE: Alvin Ailey has been a huge part of your life. Thoughts on that?

MAURICE: I’m a believer in it takes a village. Hard work and discipline. I take it seriously and I love what I do. Ailey has provided me with a lot: world travel, a livelihood, and working with talented people here and internationally. Alvin Ailey has been a huge part of my life from boyhood to now. It’s been great.

Theater

Swing actor Thomas Netter covers five principal parts in ‘Clue’

Unique role in National Theatre production requires lots of memorization

‘Clue: On Stage’

Jan. 27-Feb. 1

The National Theatre

1321 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

thenationaldc.com

Out actor Thomas Netter has been touring with “Clue” since it opened in Rochester, New York, in late October, and he’s soon settling into a week-long run at D.C.’s National Theatre.

Adapted by Sandy Rustin from the same-titled 1985 campy cult film, which in turn took its inspiration from the popular board game, “Clue” brings all the murder mystery mayhem to stage.

It’s 1954, the height of the Red Scare, and a half dozen shady characters are summoned to an isolated mansion by a blackmailer named Mr. Boddy where things go awry fairly fast. A fast-moving homage to the drawing room whodunit genre with lots of wordplay, slapstick, and farce, “Clue” gives the comedic actors a lot to do and the audience much to laugh at.

When Netter tells friends that he’s touring in “Clue,” they inevitably ask “Who are you playing and when can we see you in it?” His reply isn’t straightforward.

The New York-based actor explains, “In this production, I’m a swing. I never know who’ll I play or when I’ll go on. Almost at any time I can be called on to play a different part. I cover five roles, almost all of the men in the show.”

Unlike an understudy who typically learns one principal or supporting role and performs in the ensemble nightly, a swing learns any number of parts and waits quietly offstage throughout every performance just in case.

With 80 minutes of uninterrupted quick, clipped talk “Clue” can be tough for a swing. Still, Netter, 28, adds, “I’m loving it, and I’m working with a great cast. There’s no sort of “All About Eve” dynamic going on here.”

WASHINGTON BLADE: Learning multiple tracks has got to be terrifying.

THOMAS NETTER: Well, there certainly was a learning curve for me. I’ve understudied roles in musicals but I’ve never covered five principal parts in a play, and the sheer amount of memorization was daunting.

As soon as I got the script, I started learning lines character by character. I transformed my living room into the mansion’s study and hallway, and got on my feet as much as I could and began to get the parts into my body.

BLADE: During the tour, have you been called on to perform much?

NETTER: Luckily, everyone has been healthy. But I was called on in Pittsburgh where I did Wadsworth, the butler, and the following day did the cop speaking to the character that I was playing the day before.

BLADE: Do you dread getting that call?

NETTER: Can’t say I dread it, but there is that little bit of stage fright involved. Coming in, my goal was to know the tracks. After I’d done my homework and released myself from nervous energy, I could go out and perform and have fun. After all, I love to act.

“Clue” is an opportunity for me to live in the heads of five totally different archetype characters. As an actor that part is very exciting. In this comedy, depending on the part, some nights it’s kill and other nights be killed.

BLADE: Aside from the occasional nerves, would you swing again?

NETTER: Oh yeah, I feel I’m living out the dream of the little gay boy I once was. Traveling around getting a beat on different communities. If there’s a gay bar, I’m stopping by and meeting interesting and cool people.

BLADE: Speaking of that little gay boy, what drew him to theater?

NETTER: Grandma and mom were big movie musical fans, show likes “Singing in the Rain,” “Meet Me in St. Louis.” I have memories of my grandma dancing me around the house to “Shall We Dance?” from the “King and I” She put me in tap class at age four.

BLADE: What are your career highlights to date?

NETTER: Studying the Meisner techniqueat New York’sNeighborhood Playhouse for two years was definitely a highlight. Favorite parts would include the D’Ysquith family [all eight murder victims] in “A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder,” and the monstrous Miss Trunchbull in “Matilda.”

BLADE: And looking forward?

NETTER: I’d really like the chance to play Finch or Frump in Frank Loesser’s musical comedy “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.”

BLADE: In the meantime, you can find Netter backstage at the National waiting to hear those exhilarating words “You’re on!”