National

Locked up in the Land of Liberty: Part IV

Yariel Valdés González remained in ICE custody until March 4, 2020

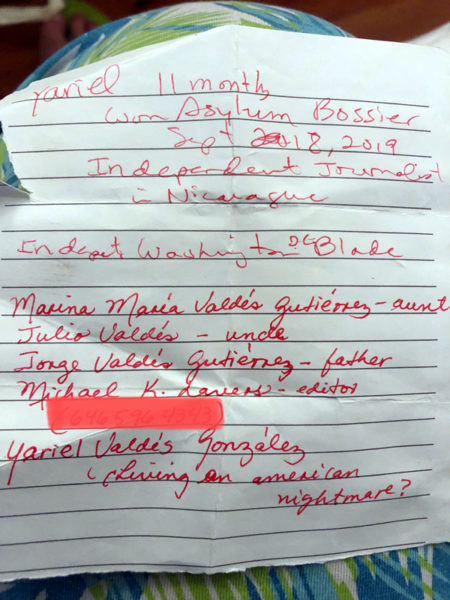

Editor’s note: Washington Blade contributor Yariel Valdés González fled his native Cuba to escape persecution because of his work as an independent journalist. He asked for asylum in the U.S. on March 27, 2019. He spent nearly a year in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody until his release on March 4, 2020.

Valdés has written about his experiences in ICE custody that the Blade has published in four parts. The Blade has already published parts I, II and III.

Bossier vs. River (Jan. 13, 2020)

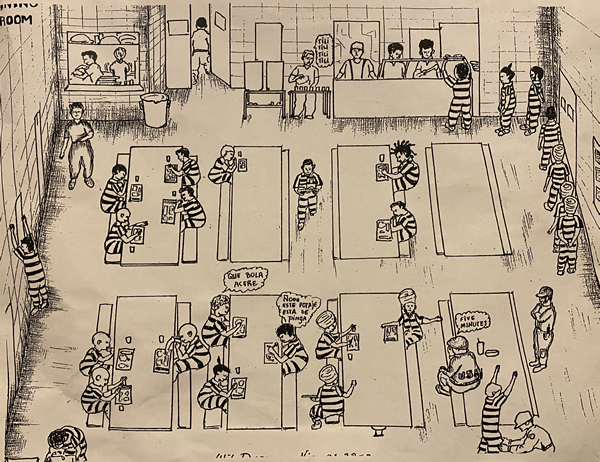

Only a few days outside Bossier confirmed my suspicions: I was being held at a military academy. The disciplinary regime and, above all, the treatment of those officers seemed more like training for a “Marine” than rules of an immigration detention center. I think that, together with many other negative aspects, precipitated our release from that prison. Previous inspections should have raised a red flag about Bossier.

My current detention center surpasses the previous one in every way. The food, for example, is much more abundant, better prepared and varied. I almost cried with joy when I saw a large quantity of chicken on my tray. At Bossier they only gave us a few shreds of chicken drowned in a dark peppery sauce.

There is also a thermos with constant soda and a cooler that never runs out. But that’s not the best thing. They gave me sneakers, socks, flip flops, gloves, pants, two blankets, a towel, a pillow, underwear, two sheets and a complete hygiene kit that includes soap, shaving cream, shampoo, toothpaste, brush and deodorant when I arrived.

My comrades here say that I can request a toiletry item whenever I want. I don’t have to go to the small window under the television through which an officer watches us 24 hours a day. What you had to buy at abusive prices at Bossier is totally free here.

They also provide us razors. To request it, you just have to hand over your ID, and they will not return it to you until you return the blade in perfect condition. The Imperial Regional Detention Facility in Calexico, the first detention center to which I was transferred, had the same rule.

It is wonderful to be able to remove unwanted hair from your face again with the ease of a razor whenever you need it. I was forced to shave with commonly used clippers for months. Laundry service is every day and commissary prices are substantially lower.

But one of these benefits in particular left me totally stunned. We can order pizza and food from restaurants, an unthinkable option in Bossier and one that I had never experienced in previous prisons.

Those who clean the pod are paid $1 a day, as are barbers. Kitchen work is reserved for common prisoners, who reside in pods outside the main building, but within the prison itself.

Living conditions are considerably better, although the pod is much smaller and a bit overcrowded. The cable television has an infinite number of channels, and some of them are even in Spanish. A curtain provides some privacy from the bedroom to shared showers, and a fragrance tablet in the urinals maintains a pleasant smell in that area.

There are three microwaves for heating or cooking food that are available from 5 a.m. until midnight. Telephones and television are available during the same hours. The only thing I miss are the tablets and the screens where I could receive video calls, text messages and photos. River, instead, offers the possibility of having visits from lawyers, family or friends, a right prohibited in Bossier that they were probably violating.

My new comrades tell me access to the yard is one hour almost everyday, unless there is some inconvenience such as bad weather or another issue. It is spacious, with basketball and volleyball courts and a covered seating area.

I went there for the first time yesterday. I jogged for several minutes while listening to radio stations in the area. The radios in River, by the way, are free with a couple of batteries. A tiny radio at Bossier cost $35 and the two batteries were not included. They had to be purchased at a cost of $2.80. Luckily, I still have my radio in good condition. It is a door to the outside world that I can open whenever I want.

The migrant population is made up of Chinese, Cameroonians, Central Americans, Armenians, Nepalese and, of course Cubans. The atmosphere so far is quite calm. I have only made a few friends in the dorm. I was placed in Alpha, the first of the dorms, however, my closest friends were placed in Charlie.

The rest of the immigrants who remained in Bossier upon our departure were also relocated here. I already sent the warden a request to change pods and he came to see me today. He was not very committed to the move, but I still hope that in the next few days it will be possible. My only company so far is loneliness.

This afternoon I joined an exercise group in a corner of the pod in the hope that I would make some new friends. I sometimes play cards with some Central Americans, but it is not the same here. I miss the bullshitting nonsense too much and the level of empathy we had built.

There is also the possibility of a new transfer. Older residents say that immigrants whose cases have been appealed are quickly sent to another detention center because this place is reserved for those who are still attending court hearings.

Many of the judges who handled the cases at Bossier have jurisdiction here as well; including the dreaded Crooks, Brent Landis, Cole (the judge who granted me asylum) and a magistrate named Angela Manson. River is Bossier’s twin for immigration processes with a low rate of asylum attained and bail granted. Parole is still denied. What does make a huge difference is the treatment of the officers. Civilians, not policemen, guard us. There is an atmosphere of respect, kindness and even humor. The officers, men and women, joke and laugh with us as if we were their friends.

Parole: Truth or myth? (Jan. 20, 2020)

This day started with an order that three ICE officers who unexpectedly killed the stillness of the morning slumber at 8 a.m. repeated. They invited us all to get up and listen to the information about parole they brought.

They gave us a notice about parole requests. They made us sign and place our right thumbprint on that document. They insisted that we all had to sign it, even those of us who were not entitled to it. They needed proof that they had informed us of the latest news concerning parole, a right they themselves had crushed.

“On Sept. 5, 2019, a federal district court ruled that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) through its Regional Office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement of New Orleans (NOLA-ICE) must ensure that all persons who are subject to that directive and who have been denied parole prior to Sept. 5, 2019, and are applying for parole are processed from according to various procedures,” the document reads.

We had already seen the same document in Bossier a few weeks before, but the situation had not changed. We viewed the announcement at the time as an institutionalized mockery of us.

The paper said we had a right to parole that a federal court had upheld, but ICE refused to release anyone under that directive. This could be another diversionary strategy to make us believe that they are following the federal court’s orders. Over the last few days, however, I have heard that several immigrants here in Louisiana have been released on parole.

The lawsuit the Southern Poverty Law Center filed against ICE is apparently bearing some fruit. According to the information, the immigrants who have been released are in the appeals process, like me. I want to be positive about this news and I hope it doesn’t fade away, like so many others that have come to raise our spirits for a few hours.

I am right now trying to contact my attorney to submit a request for redetermination of my parole, denied a few days after my “credible fear” interview in Tallahatchie last April. I have letters of support from my family in this country, from my colleagues at the Blade and from other people and institutions who will support me and ensure my well-being if I manage to get out of this confinement.

Victory in my asylum appeal is the other way for my release. Today marks two months since the transcript of my final hearing was sent. I have waited 60 days for a decision from the Virginia court (the Board of Immigration Appeals), which generally takes that long or less to send a decision.

A friend a few days ago told me the answer is positive when an order takes longer than usual to be issued. I honestly don’t know what to believe, but the tension builds in my mind every day as I try to survive pessimism. I check the phone information system every afternoon in desperate search for a phrase that would once again bring me comfort, but nothing.

“Pending,” says the metallic voice through the earpiece and my heart sinks.

An ICE officer with whom I discussed my case a few days ago gave me the same answer yesterday.

“What has your lawyer done for you?” the officer with Asian features asked me.

I replied that I have no right to bail, that parole was closed in this state and I could only wait for the appeals court’s decision.

The officer suggested that my attorney should request a determination of my parole, now that new winds are blowing. The truth is that parole is presented to me with more signs of myth than reality. I no longer know if I am living in a fantasy world or in the real world.

Hugs between brothers (Feb. 1, 2020)

Michael came to see me as soon as he found out that he could visit me in my new “home.” Bossier, my previous detention center, blocked all physical contact with family and friends during the seven months I was there. It only allowed legal visits. They told us that we had video calls when we asked about the reason for the ban. Those were our visits, as if the screen of a tablet could be comparable to physical contact. The video calls did have their advantages, but they could never replace the warm hug of someone who loves you well.

Michael arrived for the afternoon visit between 1-3 p.m. The other visitation hours are between 8-10 a.m., always from Tuesday to Sunday. I did absolutely nothing. The procedure is usually very simple and accessible. They only require an ID from the visitor and that they come on the days and times available.

An officer searched me for anything illegal, including two envelopes with documents, which I intended to give to Michael, as I left the pod. The place for visits is a fairly large room with metal tables and benches, identical to the ones we have inside the pod.

It is decorated with two paintings on the walls: A poorly done lake scene was in front of me and a rather simple reproduction of the Last Supper was to my right. There are two vending machines with candy and soft drinks, which the visitor can buy for the person who they come to see, in one corner.

The room is near one of this prison’s three courtrooms and is also used to enter and leave. Michael was waiting for me at one of the benches. He received me with open arms and his eyes clouded with sadness. I have suffered through this confinement, and he has also experienced it as his own.

We greeted each other with a hug of brothers, because that is what we have become during this time. He is the older brother I never had and our ties are getting stronger every day. The excitement over the meeting exploded in him as he hugged me. I felt his sobs on my shoulder, while at the same time his strength made me feel like we were family again.

“It’s okay, it’s okay,” I told him, and we sat down to talk.

We spoke under the protection of that complicity that has always united us and under the guise an Latina officer. I think she is Puerto Rican. She sat close enough to us to eavesdrop on the conversation. She brought a notebook and wrote observations in it.

This is only the second time we’ve met in person. The first was in Tijuana more than a year ago, when we worked together in Baja California for the Blade. I met him at the pedestrian gate on the Mexican side of the border and this time I received him in a prison on the American side. I never imagined that our friendship would take such a dramatic turn, but what I always knew was that I had added an incredible human being to my life.

He updated me on my family, our mutual friends and mine who have followed every step of my process. He held my hands tightly when my emotions got the better of me. I don’t know how, but I could feel the pounding of his heart.

“I’m here. Everything will be fine. We will win this battle soon,” he said encouragingly.

This meeting also made me smile, even though it brought tears to my eyes. Michael came ready to make me smile with his witty ideas. He told me that he had already made plans with some of his friends in Miami for after my release, including a big celebration. I really need a big party after all of this. I am, however, a realist and I don’t get too excited because disappointments can hurt more. First things first: Get out of ICE custody.

I brought him as a gift a custom-made bracelet made of black and white nylon because he came dressed in a black sweater over a white shirt. I also brought him a small handmade shoe that some comrades make here with bags of goodies. This one was specifically made with Maruchan soup wrappers of various flavors. It came out as a colorful souvenir, which he said will be an ornament on his Christmas tree.

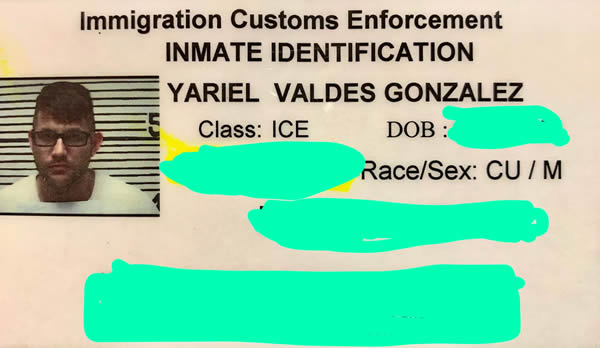

I adore every detail that I gave him, which can never be compared with all the unconditional and selfless help from him. River officials did not allow him to take with him the two envelopes with the manuscripts of these chronicles and other articles. The spy officer was extremely efficient and had already consulted with her supervisor. They luckily allowed him to keep the shoe, the bracelet and a copy of the photo that they took of me when I arrived at this prison. I half-hid it so that my family and friends could see me, although the truth is more scary than pleasant.

We talked about me getting a tattoo in reference to this period in my life. Something so profound to push me to leave a permanent mark on my skin has not happened to me before. I have always believed that tattoos should be inspired by a significant event in someone’s life. It has arrived without a doubt.

I plan to write on my body the phrase “always be free” or something similar with rainbow colors, although my terror of needles still slows me down a bit. Michael, coincidentally, told me that he too wanted to get one with a reference to “freedom.” I learned in a call two days after his visit that he had the word “libertad” or “freedom” in Spanish tattooed on one of his arms in New Orleans.

I never thought he would do it so quickly. That tattoo is yet another proof of how important I am to him. The two-hour visit was too short. Time slipped through my fingers and I very quickly saw myself saying goodbye to my brother as I received him: With a sincere, deep hug and with the hope that it would be the last visit behind bars.

Locked Up with Homophobia (Feb. 10, 2020)

Perhaps the most commonly word in my pod is “faggot,” as crude as it sounds. It was in Bossier and continues to be in the River. The word has no borders. It manages to cross languages, cultures and countries. Everyone, without distinction, learns it and uses it excessively, almost always as a “joke” between comrades.

Homophobia, however, is behind that “harmless” joke. I have personally never felt slighted for being gay in these detention centers, but the comments and conversations I hear on a daily basis are clear evidence of a less than tolerant environment.

When they say “faggot” to someone, it is with the intention of insulting them, as though being gay was the worst thing that could happen to someone. Some in here prefer to be rude, confrontational, vulgar and even a thief than a homosexual. While most say they have nothing against gays, their attitudes sometimes reveal otherwise.

There is even a Honduran in his 30s who pretends to be gay all-day long. He creates, at least for me, a completely offensive character. He uses specific phrases and imitates effeminate behaviors. It is sheer joy for the rest of them, especially when they talk about the “maricavirus,” a prison strain of the coronavirus pandemic that originated in China and is spreading everyday throughout the United States and around the world.

Someone may have been infected with the “maricavirus” if they are not “macho” enough. They say the danger of catching it inside here is high.

One can file a discrimination complaint in situations like this one. These institutions generally act by moving the aggressor to a different pod or they can take other actions, depending on the incident’s magnitude. I have made several friends who have been direct victims of homophobia, the evil from which they have been fleeing in their native countries. They find it ingrained here in some immigrants, especially those who are of Latino descent.

I have also met comrades who pretend to be gay for their asylum cases, and suffer from deep homophobia. They take advantage of the fact that they have arrived in a country where everyone’s rights — and especially where the freedoms and achievements of the LGBTQ community are respected after an intense struggle — are protected.

Just as there are people who despise us, others take advantage of our preference. Some believe that being gay means we are willing to provide “sexual favors” because of the stark isolation into which this confinement forces them. I have luckily never found myself in such a situation, but it happens. I treat everyone with great respect and receive the same from my comrades. I can only let my guard down with a few of them because we have a certain confidence with each other and joke about gay issues. One cannot always be so boring.

I lack a true friend with whom I can speak openly, although I have comrades with whom I have been for many months. I am too careful and I don’t usually expose my life or my feelings so easily.

They placed my gay friends in other pods once we arrived in River. They did not grant my request to live in the same pod with them. Most of them today are no longer in this detention center. They have been transferred as part of their deportation processes, while I feel more and more alone in this fight for my freedom that seems to never end.

A horrible possibility lurks on Monday (Feb. 24, 2020)

Nothing significantly important has happened to me during the approximately 15 days since I last wrote. My appeal remains “pending,” as does my life, frozen in this concrete cage, isolated from everything and everyone. Some things have changed over these days.

ICE granted parole to three people in this pod: A Cameroonian, a Cuban and a Mexican embraced probation to continue their process with their families, a possibility that is forbidden for me because, as my lawyer has explained to me, the cases that are on appeal always don’t qualify to obtain this benefit. It doesn’t matter that I won my case and I don’t have a deportation order.

ICE is simply not interested and will keep me here until I get a response from Virginia. I must definitely adapt to that idea. They are not going to release me when they themselves do not consider that I deserve asylum. It will not happen.

My lawyer during her visit with me on Sunday asked my permission to propose the Southern Poverty Law Center file a lawsuit against ICE because of the injustice they are committing against me and other immigrants.

ICE’s own statutes, according to Lara, state an immigrant who is entitled to asylum must be released immediately, even if the government later requests that the Board of Immigration Appeals review the case. They are violating their own policies, but I am not surprised because they had done it before with parole and they are beginning to see some results after several months of legal battles. I can’t expect a short-term result from that lawsuit and I most likely won’t benefit from it, but it can help prevent future injustices. I will not refuse to cooperate.

I certainly never thought America was like this. The champion of human rights, fighter of injustices throughout the world, closes it’s doors to those confined within its borders, all because of the hatred and xenophobia that Donald Trump’s administration has imposed against us. It is doing everything possible to expel us from here, and nothing to help us.

Another development over the last few days came via a communication with Farook Sha, a Pakistani friend who is in the same situation as me. He learned through a brief exchange of messages that a friendly correctional officer facilitated that the Virginia court denied him asylum. He must once again go before a judge for a new decision in his case. He also let me know it is possible that he is eligible for protection in this country under the U.N. Convention Against Torture or a withholding of deportation, since, as I understood him, he cannot be sent back to his country of origin.

The news obviously shattered him and further deepened the fear of failure. It has now been three months after the delivery of the arguments of my appeal and there is still no decision. This uncertainty is wearing me down every day.

I check the automatic case reporting system in the morning and in the afternoon for some consolation, but the answer remains the same. I will be in detention for 11 months in a few days. It is easy to say, but it has been one of the most terrifying experiences of my life that I do not wish on the worst of my enemies, if I have any.

Lara has prepared me for the worst possible scenario: I lose the appeal and face deportation to Cuba, where the situation is increasingly suffocating for independent journalists. She said we would have to file another appeal at the federal level in that case and we will continue the fight. She must have seen my face of horror because she immediately stopped in her tracks to say, “of course if you are willing to continue.” I didn’t know how to answer her, I still don’t know. I try not to think about that horrible possibility.

Hopelessness and hope for a weekend (Feb. 28, 2020)

The phone system for detained immigrants finally gave a different phrase today. By pressing the appeal box, the respondent informs me that “there is no information about any appeal in your case.” (She previously stated that my appeal was “pending.”) The box on the judge’s decision also says “pending.” (The phone before today indicated that the magistrate had ordered my release.)

That change set off my alarms. It made me think of thousands of possibilities. The Board of Immigration Appeals had already made its ruling, but the phone system did not specify it. The information was extremely ambiguous, yet I began to think about the possibility of my release.

I contacted Michael to find my attorney, the only one who could shed some light on the situation. I received her interpretation a few hours later. Lara said the news was not very promising. That to her meant that the Virginia court agreed with some of the arguments DHS presented in reviewing my case.

The news, through Michael’s muffled voice, completely broke me. All my hopes were shattered and I felt as though darkness took hold of me. I was shattered when I hung up and my mind once again began to betray me, thinking of the worst: A deportation order. My attorney would meet with me tonight to talk more calmly about next steps.

Lara confirmed her suspicions during our visit, but she could not assure anything with absolute certainty because she had not received the board’s letter with the final decision.

“We can’t know anything for sure without that document,” she said, trying to reassure me.

She recommended that I calm down a bit until we see the document, which should arrive early next week.

Even so, I couldn’t hold back my tears after I heard her words. My world was once again reeling and it could perhaps be the final shock that would bring about a tragic ending. But all was not lost and I clung to that hope to overcome the days ahead, although my body could not completely erase that feeling of defeat. My head threatened to explode and at times I felt my heart beating like a wild colt. I lost count of how many painkillers I ingested in my desperation to silence the pounding of my brain, which was constantly agitated.

Despite everything, I received an unexpected visitor on Sunday who managed to cheer me up a bit. An immigrant support group came to rescue me from depression. My lawyer in a previous meeting had asked me to receive them. I honestly didn’t think they were coming so quickly. A woman named Elisabeth Grant-Gibson opened her arms to me, giving me a warm welcome. Feeling that a stranger gives you their affection so spontaneously is something that I did not expect these days, much less in this place.

“I’m not a lawyer, I’m not from ICE, I’m just human,” she said when she introduced herself, a phrase that made me realize how restorative this meeting would be.

I told her about my situation, about my family, about my fears in Cuba and she was shocked by everything through which I have been. She told me about this humanitarian work that she does with many other people in order to bring us a little familiarity and understanding.

The group to which Elisabeth belongs visits detention centers to talk with immigrants, providing them with emotional support and fighting alongside with non-profit organizations that fight to make sure our rights are not trampled on.

I fell apart while talking with Elisabeth, although her visit was an injection of energy and love that I did not expect, but one for which I was crying out. I left that place with a smile on my lips and with a recommendation that she left me at farewell.

“Stay healthy from the body, but especially from here,” she said, pointing to her head, as she saw my despair.

Maybe she doesn’t know how much good she did; making me feel supported, loved and welcomed in this country. She gave me a little confidence in this nation and its people.

Justice delayed … but it comes (March 2, 2020)

A piece of mail with my name on it arrived. You have to leave the pod dressed in the green striped uniform to receive it. An officer outside opened the correspondence in front of me and I could see that it was the envelope with the Board of Immigration Appeals’ decision. My heart rate began to increase. Zero hour arrived. It was the moment of truth.

I hardly understood what I read on the first page, but the word “removed” left me in shock.

“It can’t be, it can’t be,” I told myself and moved on to the rest of the document. The second sheet is more enlightening and contains the verdict, which states the DHS appeal has been dismissed.

“We contribute and affirm the decision of the immigration judge (…) Contrary to the arguments of the DHS appeal, we conclude that the favorable credibility found by the immigration judge that the applicant (that is me) is eligible for asylum as he has established that he has suffered past persecution and has a well-founded fear of persecution.”

It was all I needed to read. My legs began to shake and my heart wanted to jump out of my chest. I asked the officer if I could sit down because I felt that my legs couldn’t hold me for much longer. I reread the document. I could not believe it. It confirmed that DHS had lost the fight in my case and there could no longer be any doubts about my asylum.

The nightmare finally came to an end after a 5-month long appeals process and a total of 11 months in unjust ICE detention. Justice takes time, but it always comes for those who deserve it. I gave my captors 150 more days, but I will not focus my energies on that. I must look forward, although it will of course be impossible to forget everything I have gone through to finally be free.

I will be eternally grateful to this nation for protecting me from the Cuban dictatorship, even if it put me through hell first. Americans are a tough breed to crack. I understand that they must be very careful with those who they allow to cross their borders, but I disagree with their methods.

My old comrades came over to congratulate me once I reached the dorm. I could see sincere joy on their faces and that this news renewed their hope in their particular cases. I began to call my aunt and uncles to give them the good news, the news for which we had waited so long, but they did not answer the phone.

I managed to speak with Michael and I could hear how the emotion overwhelmed him, how the tears of joy barely let him speak and we began to make the plans that we had postponed for so long. He will come to rescue me from this prison and take me to my family in Miami.

I was able to speak with my aunt and uncles a few hours later. It took them a bit to understand, because I had told them the opposite a few days. I felt my voice crack when I managed to understand.

“We won, we won!” I repeated to them and I imagine that everyone exploded with joy on the other end of the line.

I would let my parents know and I recommended they, like Michael, not post anything on social media until he finally saw me breathing freedom on the outside. It has been an exhausting fight, one that has been frustrating at times and one that has inflicted a few emotional wounds that I trust will heal very soon. I still have to get used to the idea that I will have won my asylum twice and that I will soon start my new life.

Epilogue of a victory (March 4, 2020)

I approached three ICE officers visiting the pods after I read to my attorney over the phone the contents of the letter from Virginia and verified that they were not my hallucinations. The officers — two men and a woman — arrived that morning and I showed the document that showed their defeat.

“What do you want me to do with this?” asked the officer, half annoyed after looking at the board’s order.

“I wanted to know when I’m getting out,” I said.

“Do you want to go?” she asked ironically.

“Of course,” I responded quickly

“Well, it seems that you have not read what the paper says in this part below,” she said

I began to get nervous. I sensed another dirty ruse to block my release. The officer said that my case had to go back to court with the judge who granted me asylum. It seemed completely absurd to me, because the Virginia court had agreed with Cole’s ruling and a change of decision was not necessary. But it is apparently the final step of my case, the closing of a long and harrowing process. ICE would prepare all the paperwork for my release with the judge’s order. One of the officers said the process could take a week or more.

I returned indignant and fearful, as is often the case every time I confront them. Those exchanges always leave me in a very bad mood. They returned a few minutes later to take my personal information: Future address, telephone numbers to contact me and to find out how I would get out of detention. I found out that the officers had, once again and this time for my benefit, lied to me.

An officer urgently asked for me while I was taking my last shower in prison. She said they were asking for me because I had a very important call. I thought it was Michael, who was on his way to pick me up, but no. They rushed me out of the pod, for I shouldn’t keep such a distinguished call waiting.

I suddenly found myself sitting in front of the immigration judge, who was in the same room where I had won asylum five months earlier. Lara, my lawyer, was on the phone and the voice in the background belonged to the government prosecutor in my case. It was like deja vu when a cyclical nightmare returns. The judge claimed to have received Virginia’s ruling, which upheld his sentence from months ago. He turned to the government attorney, who claimed not to have been notified of his defeat in the appeals court.

The DHS representative did nothing but stall until the last minute, but His Honor affirmed that everything was ready for my release. He asked if the officers had processed my exit documents and he wished me good luck before ending the hearing. I could perceive a certain feeling of joy in the judge, because his work was impeccable. I thanked him once again and breathed easy as I left the hearing.

Practically all of the belongings that I would take with me were packed when I returned to the pod. I had given things that I would not need to friends, especially those who still had a few months of anguish left. I was scheduled to leave at 2 p.m., and it happened.

Some Cuban and other friends came over to say goodbye when they came for me. It is highly unlikely that our paths will cross again. This time it was me who could see in their faces the joy intertwined with the pain of staying in confinement. They smiled, hugged me and congratulated me … it felt sincere.

It had been raining mercilessly outside from the early hours of the morning. Through the pod’s tiny windows I had seen how the grass could not soak up so much water from the storm, but nothing could darken this day, not even those clouds that turned the afternoon gray and threatened to soak me. I didn’t care!

The check-out process was easy. The officer in charge of my release gave me a laminated ID card with my personal information. The first photo they took of me when I entered this country 11 months ago was on the back. I asked about my passport, but that ID was the only thing ICE would give me with which I could travel. It would have to do! I finally shed that infamous green and white striped jumpsuit and felt human again when I adjusted my pants and long-sleeved shirt.

The clothes literally danced on my body. It was an unmistakable symptom of famine and all kinds of deprivation. I went through a door that I had never even approached and arrived at a small reception area where an officer verified my data. Everything was in order. My phone was dead, I couldn’t tell if it had survived the tragedy. The downpour outside the walls continued unabated, preventing me from running to be free for which I had so often longed.

My only option was to wait for Michael and I had to be patient. He told me during one of our telephone calls to confirm the details of my release that he had fallen in the morning. He was in the hospital with a broken arm, but insisted that nothing would stop him from rescuing me.

I hadn’t been waiting long when I saw him arrive. A giant t-shirt, which made it a bit difficult for him to walk, covered his arm.

We almost collided at the door. The storm outside had blinded him and we hugged tightly for a few seconds when he realized that I was the one who received him. We laughed and got excited. I finally crossed River’s threshold, never to return. We ran through the heavy downpour, which felt like a hurricane, until we reached the car. Michael started the car and I took a giant breath of air that tried to calm me down. I was free once and for all. I still didn’t believe it.

Federal Government

Trump-appointed EEOC leadership rescinds LGBTQ worker guidance

The EEOC voted to rescind its 2024 guidance, minimizing formally expanded protections for LGBTQ workers.

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission voted 2–1 to repeal its 2024 guidance, rolling back formally expanded protections for LGBTQ workers.

The EEOC, which is composed of five commissioners, is tasked with enforcing federal laws that make workplace discrimination illegal. Since President Donald Trump appointed two Republican commissioners last year — Andrea R. Lucas as chair in January and Brittany Panuccio in October — the commission’s majority has increasingly aligned its work with conservative priorities.

The commission updated its guidance in 2024 under then-President Joe Biden to expand protections to LGBTQ workers, particularly transgender workers — the most significant change to the agency’s harassment guidance in 25 years.

The directive, which spanned nearly 200 pages, outlined how employers may not discriminate against workers based on protected characteristics, including race, sex, religion, age, and disability as defined under federal law.

One issue of particular focus for Republicans was the guidance’s new section on gender identity and sexual orientation. Citing the 2020 U.S. Supreme Court’s Bostock v. Clayton County decision and other cases, the guidance included examples of prohibited conduct, such as the repeated and intentional use of a name or pronoun an individual no longer uses, and the denial of access to bathrooms consistent with a person’s gender identity.

Last year a federal judge in Texas had blocked that portion of the guidance, saying that finding was novel and was beyond the scope of the EEOC’s powers in issuing guidance.

The dissenting vote came from the commission’s sole Democratic member, Commissioner Kalpana Kotagal.

“There’s no reason to rescind the harassment guidance in its entirety,” Kotagal said Thursday. “Instead of adopting a thoughtful and surgical approach to excise the sections the majority disagrees with or suggest an alternative, the commission is throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Worse, it is doing so without public input.”

While this now rescinded EEOC guidance is not legally binding, it is widely considered a blueprint for how the commission will enforce anti-discrimination laws and is often cited by judges deciding novel legal issues.

Multiple members of Congress released a joint statement condemning the agency’s decision to minimize worker protections, including U.S. Reps. Teresa Leger Fernández (D-N.M.), Grace Meng (D-N.Y.), Mark Takano (D-Calif.), Adriano Espaillat (D-N.Y.), and Yvette Clarke (D-N.Y.) The rescission follows the EEOC’s failure to respond to or engage with a November letter from Democratic Caucus leaders urging the agency to retain the guidance and protect women and vulnerable workers.

“The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is supposed to protect vulnerable workers, including women, people of color, and LGBTQI+ workers, from discrimination on the job. Yet, since the start of her tenure, the EEOC chair has consistently undermined protections for women, people of color, and LGBTQI+ workers. Now, she is taking away guidance intended to protect workers from harassment on the job, including instructions on anti-harassment policies, training, and complaint processes — and doing so outside of the established rule-making process. When workers are sexually harassed, called racist slurs, or discriminated against at work, it harms our workforce and ultimately our economy. Workers can’t afford this — especially at a time of high costs, chaotic tariffs, and economic uncertainty. Women and vulnerable workers deserve so much better.”

Minnesota

Lawyer representing Renee Good’s family speaks out

Antonio Romanucci condemned White House comments over Jan. 7 shooting

A U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent shot and killed Renee Good in Minneapolis on Jan. 7 as she attempted to drive away from law enforcement during a protest.

Since Good’s killing, ICE has faced national backlash over the excessive use of deadly force, prompting the Trump-Vance administration to double down on escalating enforcement measures in cities across the country.

The Washington Blade spoke with Antonio Romanucci, the attorney representing Good’s family following her death.

Romanucci said that Jonathan Ross — the ICE agent seen on video shooting Good — acted in an antagonizing manner, escalated the encounter in violation of ICE directives, and has not been held accountable as ICE and other federal agents continue to “ramp up” operations in Minnesota.

A day before the fatal shooting, the Department of Homeland Security began what it described as the largest immigration enforcement operation ever carried out by the agency, according to DHS’s own X post.

That escalation, Romanucci said, is critical context in understanding how Good was shot and why, so far, the agent who killed her has faced no consequences for killing a queer mother as she attempted to disengage from a confrontation.

“You have to look at this in the totality of the circumstances … One of the first things we need to look at is what was the mission here to begin with — with ICE coming into Minneapolis,” Romanucci told the Blade. “We knew the mission was to get the worst of the worst, and that was defined as finding illegal immigrants who had felony convictions. When you look at what happened on Jan. 7 with Renee and Rebecca [Good, Renee’s wife], certainly that was far from their mission, wasn’t it? What they really did was they killed a good woman — someone who was a mother, a daughter, a sister, a committed companion, an animal lover.”

Romanucci said finding and charging those responsible for Good’s death is now the focus of his work with her family.

“What our mission is now is to ensure that we achieve transparency, accountability, and justice … We aim to get it in front of, hopefully, a judge or a jury one day to make that determination.”

Those are three things Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and DHS has outright rejected while smearing Good in the official record — including accusing her of being a “domestic terrorist” without evidence and standing by Ross, who Noem said acted in self-defense.

The version of events advanced by Noem and ICE has been widely contradicted by the volume of video footage of the shooting circulating online. Multiple angles show Good’s Honda Pilot parked diagonally in the street alongside other protesters attempting to block ICE agents from entering Richard E. Green Central Park Elementary School.

The videos show ICE officers approaching Good’s vehicle and ordering her to “get out of the car.” She then puts the car in reverse, backs up briefly, shifts into drive, and steers to the right — away from the officers.

The abundance of video evidence directly contradicts statements made by President Donald Trump, Noem, and other administration officials in interviews following Good’s death.

“The video shows that Renee told Jonathan Ross that ‘I’m not mad at you,’ so we know that her state of mind was one of peace,” Romanucci said. “She steered the car away from where he was standing, and we know that he was standing in front of the car. Reasonable police practices say that you do not stand in front of the car when there’s a driver behind the wheel. When you leave yourself with only the ability to use deadly force as an option to escape, that is not a reasonable police practice.”

An autopsy commissioned by Good’s family further supports that account, finding that her injuries were consistent with being shot from the direction of someone driving away.

The autopsy found three gunshot wounds: one to Good’s left forearm, one that struck her right breast without piercing major organs, and a third that entered the left side of her head near the temple and exited on the right side.

Romanucci said Ross not only placed himself directly in harm’s way, but then used deadly force after creating the conditions he claimed justified it — a move that violates DHS and ICE policy, according to former Assistant Homeland Security Secretary Juliette Kayyem.

“As a general rule, police officers and law enforcement do not shoot into moving cars, do not put themselves in front of cars, because those are things that are easily de-escalated,” Kayyem told PBS in a Jan. 8 interview.

“When he put himself in a situation of danger, the only way that he could get out of danger is by shooting her, because he felt himself in peril,” Romanucci said. “That is not a reasonable police practice when you leave yourself with only the ability to use deadly force as an option. That’s what happened here. That’s why we believe, based on what we’ve seen, that this case is unlawful and unconstitutional.”

Romanucci said he was appalled by how Trump and Noem described Good following her death.

“I will never use those words in describing our client and a loved one,” he said. “Those words, in my opinion, certainly do not apply to her, and they never should apply to her. I think the words, when they were used to describe her, were nearly slanderous … Renee Good driving her SUV at two miles per hour away from an ICE agent to move down the street is not an act of domestic terrorism at all.”

He added that his office has taken steps to preserve evidence in anticipation of potential civil litigation, even as the Justice Department has declined to open an investigation.

“We did issue a letter of preservation to the Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, and other agencies to ensure that any evidence that’s in their possession be not destroyed or altered or modified,” Romanucci said. “We’ve heard Todd Blanche say just in the last couple of days that they don’t believe that they need to investigate at all. So we’re going to be demanding that the car be returned to its rightful owner, because if there’s no investigation, then we want our property back.”

The lack of accountability for Ross — and the continued expansion of ICE operations — has fueled nationwide protests against federal law enforcement under the Trump-Vance administration.

“The response we’ve seen since Renee’s killing has been that ICE has ramped up its efforts even more,” Romanucci said. “There are now over 3,000 ICE agents in a city where there are only 600 police officers, which, in my opinion, is defined as an invasion of federal law enforcement officers into a city … When you see the government ramping up its efforts in the face of constitutional assembly, I think we need to be concerned.”

As of now, Romanucci said, there appears to be no meaningful accountability mechanism preventing ICE agents from continuing to patrol — and, in some cases, terrorize — the Minneapolis community.

“What we know is that none of these officers are getting disciplined for any of their wrongdoings,” he said. “The government is saying that none of their officers have acted in a wrongful manner, but that’s not what the courts are saying … Until they get disciplined for their wrongdoings, they will continue to act with impunity.”

When asked what the public should remember about Good, Romanucci emphasized that she was a real person — a mother, a wife, and a community member whose life was cut short. Her wife lost her partner, and three children lost a parent.

“I’d like the public to remember Renee about is the stories that Rebecca has to tell — how the two of them would share road trips together, how they loved to share home-cooked meals together, what a good mother she was, and what a community member she was trying to make herself into,” Romanucci said. “They were new to Minneapolis and were really trying to make themselves a home there because they thought they could have a better life. Given all of that, along with her personality of being one of peace and one of love and care, I think that’s what needs to be remembered about Renee.”

The White House

Trump-Vance administration ‘has dismantled’ US foreign policy infrastructure

Current White House took office on Jan. 20, 2025

Jessica Stern, the former special U.S. envoy for the promotion of LGBTQ and intersex rights, on the eve of the first anniversary of the Trump-Vance administration said its foreign policy has “hurt people” around the world.

“The changes that they are making will take a long time to overturn and recover from,” she said on Jan. 14 during a virtual press conference the Alliance for Diplomacy and Justice, a group she co-founded, co-organized.

Amnesty International USA National Director of Government Relations and Advocacy Amanda Klasing, Human Rights Watch Deputy Washington Director Nicole Widdersheim, Human Rights First President Uzra Zeya, PEN America’s Jonathan Friedman, and Center for Reproductive Rights Senior Federal Policy Council Liz McCaman Taylor also participated in the press conference.

The Trump-Vance administration took office on Jan. 20, 2025.

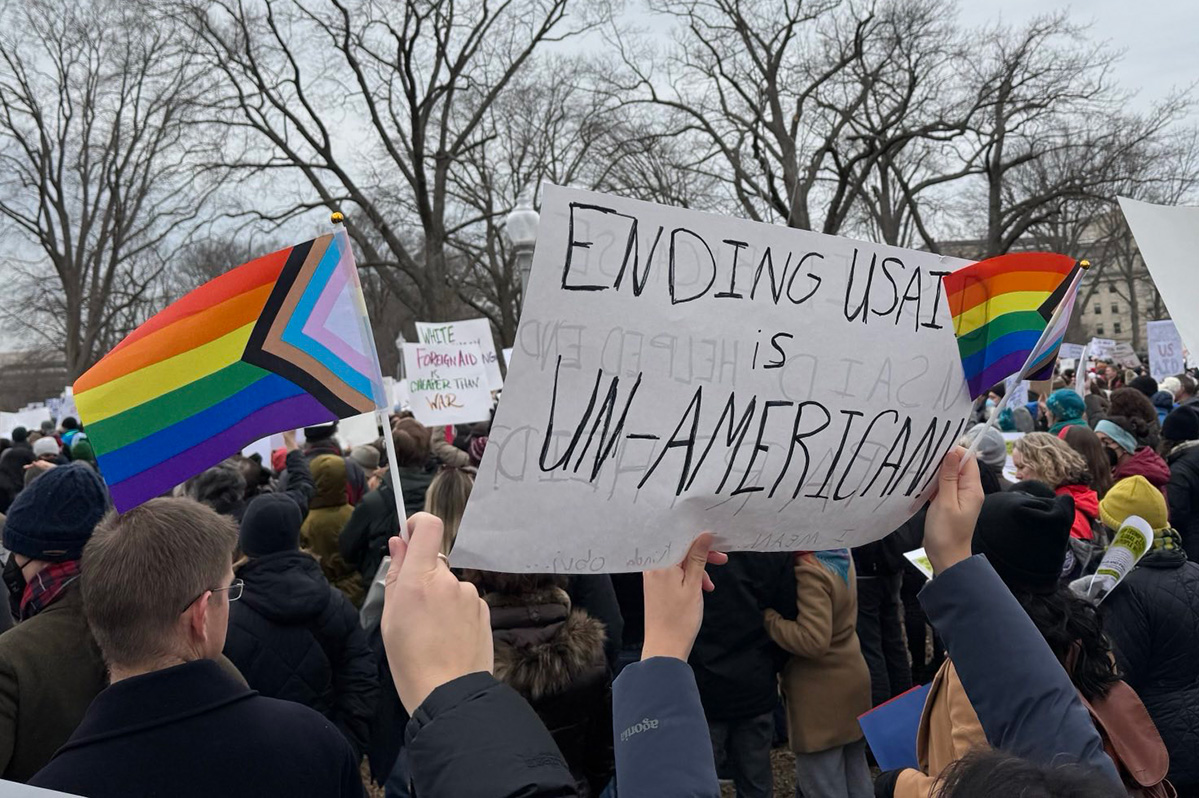

The White House proceeded to dismantle the U.S. Agency for International Development, which funded LGBTQ and intersex rights organizations around the world.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio last March announced the State Department would administer the 17 percent of USAID contracts that had not been cancelled. Rubio issued a waiver that allowed PEPFAR and other “life-saving humanitarian assistance” programs to continue to operate during the U.S. foreign aid freeze the White House announced shortly after it took office.

The global LGBTQ and intersex rights movement has lost more than an estimated $50 million in funding because of the cuts. The Washington Blade has previously reported PEPFAR-funded programs in Kenya and other African countries have been forced to suspend services and even shut down.

Stern noted the State Department “has dismantled key parts of foreign policy infrastructure that enabled the United States to support democracy and human rights abroad” and its Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor “has effectively been dismantled.” She also pointed out her former position and others — the Special Representative for Racial Equity and Justice, the Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women’s Issues, and the Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice — “have all been eliminated.”

President Donald Trump on Jan. 7 issued a memorandum that said the U.S. will withdraw from the U.N. Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and more than 60 other U.N. and international entities.

Rubio in a Jan. 10 Substack post said UN Women failed “to define what a woman is.”

“At a time when we desperately need to support women — all women — this is yet another example of the weaponization of transgender people by the Trump administration,” said Stern.

US ‘conducting enforced disappearances’

The Jan. 14 press conference took place a week after a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent killed Renee Good, a 37-year-old woman who left behind her wife and three children, in Minneapolis. American forces on Jan. 3 seized now former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, at their home in Caracas, the Venezuelan capital, during an overnight operation. Trump also continues to insist the U.S. needs to gain control of Greenland.

Widdersheim during the press conference noted the Trump-Vance administration last March sent 252 Venezuelans to El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center, a maximum-security prison known by the Spanish acronym CECOT.

One of them, Andry Hernández Romero, is a gay asylum seeker who the White House claimed was a member of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang the Trump-Vance administration has designated as an “international terrorist organization.” Hernández upon his return to Venezuela last July said he suffered physical, sexual, and psychological abuse while at CECOT.

“In 2025 … the United States is conducting enforced disappearances,” said Widdersheim.

Zeya, who was Under Secretary of State for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights from 2021-2025, in response to the Blade’s question during the press conference said her group and other advocacy organizations have “got to keep doubling down in defense of the rule of law, to hold this administration to account.”

-

The White House5 days ago

The White House5 days agoTrump-Vance administration ‘has dismantled’ US foreign policy infrastructure

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoFaith programming remains key part of Creating Change Conference

-

Virginia4 days ago

Virginia4 days agoMcPike prevails in ‘firehouse’ Dem primary for Va. House of Delegates

-

Iran4 days ago

Iran4 days agoLGBTQ Iranians join anti-government protests