Arts & Entertainment

LGBTQ youth inspired to action by “Cured” documentary and country’s homophobic past

“Cured” documentary a revelation for LGBTQ youth

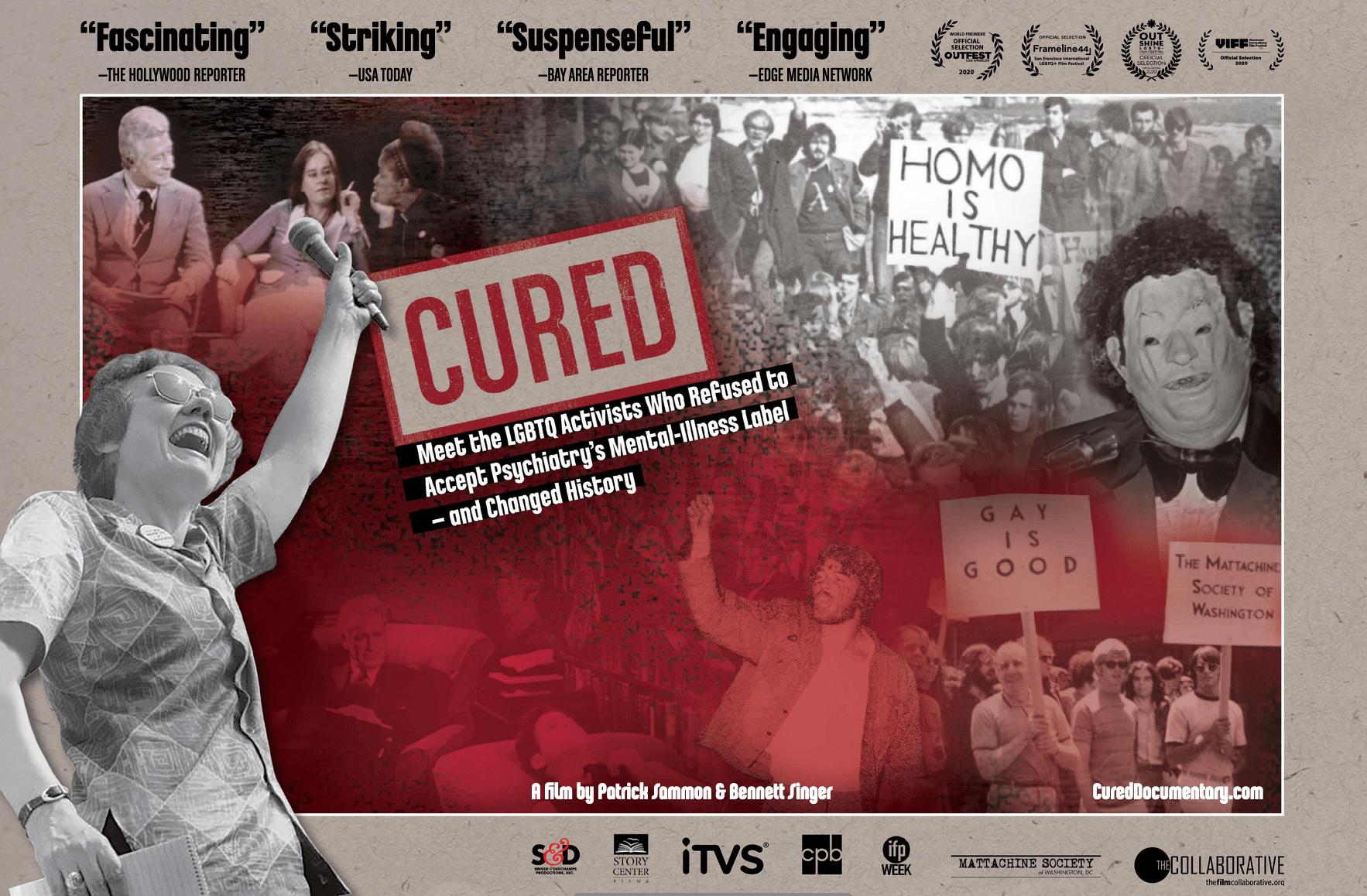

A new documentary’s archival footage of the country’s homophobic past opened the eyes of four young members of the LGBTQ+ community who were only dimly aware of the events the film describes.

“Cured,” which aired on PBS’ Independent Lens on October 11, was a revelation to the youth– who work with the D.C.-based Urban Health Media Project on multimedia health journalism.

Some of the scenes that made an impression:

- At a 1966 South Florida high school assembly on the evils of homosexuality, an official warns students that “if we catch you … the rest of your life will be a living hell.’’

- A gay psychiatrist, appearing on a 1972 American Psychiatric Association panel, is identified only as “Dr. Henry Anonymous.” He’s so afraid of reprisals that he must protect his identity by wearing a Halloween face mask and a fright wig and using a distortion mic.

- A series of sober, eminent psychiatrists – leaders of the profession – insist in forum after forum that homosexuality is a sickness.

For two decades, that assumption was reflected in the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM),” the American psychiatric profession’s official compendium of mental and brain diseases and disorders.

“Cured” tells the story of how a relatively small number of courageous gay activists got the “gays are sick” notion struck from the manual –a pivotal moment in the gay liberation movement.

“Being gay and trans myself,’’ said Hermes Falcon, “this film meant a lot to me, because it exposed me to people that I didn’t even know were part of the movement.’’

Those people included Barbara Gittings and Frank Kameny, who in the mid-1960s – when most Americans still said they feared or hated homosexuals — organized some of the first public protests against employment discrimination against gays. One depicted in “Cured”took place outside the White House.

Another early activist was Dr. John Fryer, the psychiatrist who, it later turned out, was “Dr. Anonymous.’’

Falcon, a college freshman, also noted the tension at the heart of the story told by “Cured”: “How working together makes a big difference, but also how one person can make a big change.’’

Falcon cited the example of Fryer, who testified at the APA convention in Dallas in 1972 that anti-gay bias was hurting psychiatrists, too. At that point, the DSM’s entry 302.0, which termed homosexuality “a mental disorder,” was two decades old. Within two years of Fryer’s testimony, it had been abolished.

Another young member of the LGBTQ+ community, Adrian Gibbons, an assistant video editor at UHMP and recent college graduate, also was struck by the example of Fryer, “a real person who was risking his job to stand up for himself and the LGBTQ community.’’ His example, Gibbons said, “inspires me to fight for myself and my community, no matter the risks.’’

Gibbons noted that some trailblazers faced a harsh backlash from colleagues or family members. But he said their sacrifice was worth it, considering that “their efforts brought justice to LGBTQ people who had been injured or abused in mental institutions, and saved countless people from being put through that same torture in the future.’’

Torture is probably not too strong a word; “Cured” shows how electroshock and even lobotomy were used as elements of “conversion therapy’’ to make gay people straight.

The early activists’ sheer courage also inspired Dillon Livingston, a high school student. The film shows, he said, that “it is imperative to remain true to yourself, even if everyone around you does not like the things that make you who you are.’’

Even though they faced intense discrimination and disdain, he added, the gay rights pioneers “were proud about their sexuality.’’

The four young LGBTQ+ viewers agreed that “Cured”made them more appreciative of the efforts of those who went before them, and more eager to emulate their example in the future.

As Livingston put it, “I must speak more about the queer community to inform heterosexuals about the problem we face.’’

Jojo Brew, an aspiring filmmaker, agreed: “All those people in the sixties and seventies fought for our rights, so it’s only fair that we continue to fight for the next generation’s rights.’’

“Cured” airs locally at 9 p.m. Oct. 21 on WHUT. After its broadcast premiere Oct. 11, the film will be available to stream for free on the PBS app and website for 30 days. The documentary will be rebroadcast a few more times over the next three years and eventually released on streaming platforms.

Arts & Entertainment

2026 Most Eligible LGBTQ Singles nominations

We are looking for the most eligible LGBTQ singles in the Washington, D.C. region.

Are you or a friend looking to find a little love in 2026? We are looking for the most eligible LGBTQ singles in the Washington, D.C. region. Nominate you or your friends until January 23rd using the form below or by clicking HERE.

Our most eligible singles will be announced online in February. View our 2025 singles HERE.

The Freddie’s Follies drag show was held at Freddie’s Beach Bar in Arlington, Va. on Saturday, Jan. 3. Performers included Monet Dupree, Michelle Livigne, Shirley Naytch, Gigi Paris Couture and Shenandoah.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

a&e features

Queer highlights of the 2026 Critics Choice Awards: Aunt Gladys, that ‘Heated Rivalry’ shoutout and more

Amy Madigan’s win in the supporting actress category puts her in serious contention to win the Oscar for ‘Weapons’

From Chelsea Handler shouting out Heated Rivalry in her opening monologue to Amy Madigan proving that horror performances can (and should) be taken seriously, the Critics Choice Awards provided plenty of iconic moments for queer movie fans to celebrate on the long road to Oscar night.

Handler kicked off the ceremony by recapping the biggest moments in pop culture last year, from Wicked: For Good to Sinners. She also made room to joke about the surprise hit TV sensation on everyone’s minds: “Shoutout to Heated Rivalry. Everyone loves it! Gay men love it, women love it, straight men who say they aren’t gay but work out at Equinox love it!”

The back-to-back wins for Jacob Elordi in Frankenstein and Amy Madigan in Weapons are notable, given the horror bias that awards voters typically have. Aunt Gladys instantly became a pop culture phenomenon within the LGBTQ+ community when Zach Cregger’s hit horror comedy released in August, but the thought that Madigan could be a serious awards contender for such a fun, out-there performance seemed improbable to most months ago. Now, considering the sheer amount of critics’ attention she’s received over the past month, there’s no denying she’s in the running for the Oscar.

“I really wasn’t expecting all of this because I thought people would like the movie, and I thought people would dig Gladys, but you love Gladys! I mean, it’s crazy,” Madigan said during her acceptance speech. “I get [sent] makeup tutorials and paintings. I even got one weird thing about how she’s a sex icon also, which I didn’t go too deep into that one.”

Over on the TV side, Rhea Seehorn won in the incredibly competitive best actress in a drama series category for her acclaimed performance as Carol in Pluribus, beating out the likes of Emmy winner Britt Lower for Severance, Carrie Coon for The White Lotus, and Bella Ramsey for The Last of Us. Pluribus, which was created by Breaking Bad’s showrunner Vince Gilligan, has been celebrated by audiences for its rich exploration of queer trauma and conversion therapy.

Jean Smart was Hack’s only win of the night, as Hannah Einbinder couldn’t repeat her Emmy victory in the supporting actress in a comedy series category against Janelle James, who nabbed a trophy for Abbott Elementary. Hacks lost the best comedy series award to The Studio, as it did at the Emmys in September. And in the limited series category, Erin Doherty repeated her Emmy success in supporting actress, joining in yet another Adolescence awards sweep.

As Oscar fans speculate on what these Critics Choice wins mean for future ceremonies, we have next week’s Golden Globes ceremony to look forward to on Jan. 11.

-

Photos4 days ago

Photos4 days agoThe year in photos

-

Sponsored3 days ago

Sponsored3 days agoSafer Ways to Pay for Online Performances and Queer Events

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoTwo pioneering gay journalists to speak at Thursday event

-

a&e features2 days ago

a&e features2 days agoQueer highlights of the 2026 Critics Choice Awards: Aunt Gladys, that ‘Heated Rivalry’ shoutout and more