Books

Politics, sex, activism highlight memoir on AIDS survival

POZ magazine founder Strub recounts journey from Capitol Hill to HIV fight

Sean Strub’s new memoir revisits closeted Washington in the ‘70s and the AIDS fight in New York. (Photo courtesy Public Impact Media Consultants)

Sean Strub’s newly published book Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics, Sex, AIDS, and Survival provides a vivid, first-hand account of how his own struggle with AIDS intersected with his role as an AIDS activist during the tumultuous early years of the epidemic in New York City.

But Strub, 55, also reveals a part of his life that those who know him as founder of the influential AIDS publication POZ magazine may not have known – his political and personal coming out following his move to Washington, D.C., from his home state of Iowa in 1976 at the age of 17.

After delaying his start at Georgetown University for a year to work on political campaigns in Iowa and through help from then-Sen. Dick Clark (D-Iowa), Strub landed a patronage job as an elevator operator at the U.S. Capitol in March of 1976.

“I couldn’t imagine anything more exciting for an ambitious political junkie than employment literally a few steps away from the Senate chamber,” he writes in his book.

Strub is scheduled to read from his book and take questions from listeners Tuesday night, Jan. 28, at D.C.’s Politics and Prose bookstore at 5015 Connecticut Ave., N.W., from 7-9 p.m.

As Strub tells it, over the next three years (from 1976-1979) he cautiously came to terms with his status as a gay man after having struggled with self-denial in his younger years. His gradual evolution toward self-acceptance, he writes, came in part through the help of closeted gay men in influential political positions in Washington and later in New York who became his mentors.

Like them, Strub writes, he became comfortable with his own sexual orientation but remained deep in the closet, fearing that public disclosure of his “hidden” life would destroy his long-held aspirations to become involved in politics and public policy making. His earlier dream of one day getting elected to public office would no longer be possible due to his sexual orientation, he concluded during the years from the late 1970s to early 1980s.

Before going on to chronicle his early career operating a direct mail fundraising business while helping to raise money for AIDS-related causes, Strub provides a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the closeted gay scene in the nation’s capital in the late 1970s.

Gay men of the Baby Boom generation who lived in D.C. at that time will likely relate to Strub’s stories about meeting and befriending Capitol Hill staffers and others involved in politics at the Lost and Found, the then highly popular gay disco located in a hidden warehouse district in Southeast D.C. less than a mile from the Capitol.

“Going to the Lost and Found marked my first appearance in a public gay venue, and that felt irreversible, crossing a threshold from which I could not return,” he writes.

“I learned that meeting gay men in a gay context – whether at a bar, private party or other circumstance – invoked an unspoken omerta-like agreement not to share the secret life with others, even if it meant pretending we didn’t know each other,” he says in the book.

Among those who became his mentor was Washington political operative turned journalist Alan Baron, publisher of the widely read Baron Report on Washington politics. Others – both gay and straight – gave him what he called the equivalent of a Harvard MBA in the field of fundraising through direct mail and telemarketing techniques.

Still others introduced him to the world of gay sex and gay male cruising spots both in D.C. and during his first few years in New York. It was at a time just before AIDS burst on the scene that epidemiologists later described as a “perfect storm” for the sexual transmission of HIV between men who have sex with men.

Through a friend he met at the D.C. gay bar Rascals, Strub says he was invited to a dinner party in 1978 at the home of D.C. gay businessman Bob Alfondre and his partner Carroll Sledz. Strub says it was there that he met and became friends with famed playwright Tennessee Williams, a guest of honor at the dinner party, who later invited Strub to visit him at his home in Key West, Fla.

Other VIPs with whom Strub met and befriended in subsequent years included Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Gore Vidal and Larry Kramer.

In what his activist friends considered a major coup, Strub tells of how he mustered all of his courage and salesmanship in 1982 to persuade Tennessee Williams to sign his name to a fundraising letter for the Human Rights Campaign Fund, an arm of the then Gay Rights National Lobby that became the forerunner to today’s Human Rights Campaign.

The letter was written by Baron at the request of Steve Endean, the executive director of GRNL and whose idea it was to create the HRCF. Among other things, the letter urged potential donors to give money to HRCF, a political action committee or PAC, to help prevent anti-gay candidates backed by the Rev. Jerry Falwell from getting elected to Congress.

“I emphasized how influential the new PAC would be and how critical his signature on the letter would be to its success,” Strub wrote in describing his pitch to Williams at a hotel room in New York City where Williams was staying at the time. When Strub entered the hotel room Williams was dressed in pajamas and a bathrobe and had a glass of wine in his hand.

“I said he could set a powerful example to others,” Strub wrote. “Getting him to sign the letter, I declared, would be the most important thing I had ever done in my life.”

Over the next 90 minutes or more Williams talked about his plans for a new play and all kinds of things unrelated to the letter. At one point the then 24-year-old Strub nearly froze when Williams asked him what he would do to persuade him to sign the letter, thinking Williams might be making a pass at him, Strub writes.

“Almost anything, but I hope I don’t have to,” Strub says he replied.

Finally, thinking Williams was politely indicating he wouldn’t sign the letter, Strub got up from where he was sitting and put on his coat and walked toward the door. “Wait a minute, baby, what about your letter?” Strub quotes Williams as shouting.

The famous playwright signed the letter, which, according to Strub, became the most successful gay rights fundraising appeal to date, generating over 10,000 new donors to the gay rights cause and paving the way for the future HRC to become the nation’s leading LGBT rights organization.

Strub’s success in getting Tennessee Williams to sign the fundraising letter came after he moved to New York in 1979 to continue his studies at Columbia University. A short time later Strub and various partners established a direct mail fundraising businesses that did work for gay rights and other progressive causes as well as for Democratic Party candidates running for public office.

By the mid-1980s, around the time he discovered he was HIV positive, he helped raise money for AIDS advocacy groups, including New York’s pioneering Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the American Foundation for AIDS Research (AmfAR), and ACT UP.

NIH official Fauci disputes claim he was ‘uncooperative’

By 1987, Strub says he became further disillusioned over the federal government’s response to AIDS when fellow activist Michael Callen told him about a tense meeting in May of that year between Callen and several other AIDS activists and Dr. Anthony Fauci, who headed AIDS research programs at the National Institutes of Health.

Callen and the other activists urged Fauci to arrange for the NIH to issue guidelines recommending that doctors treating AIDS patients prescribe the drug Bactrim as a prophylaxis to prevent the onset of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, the opportunistic infection that killed most people with AIDS at the time. Strub notes that Callen cited promising results in New York and other places where AIDS doctors, especially New York physician and researcher Joseph Sonnabend, reported Bactrim was succeeding in preventing patients from contracting the deadly pneumonia.

“Fauci was uncooperative,” Strub reports in his book. “He dismissed previous research, saying he wanted data proving that prophylaxis [Bactrim] helped prevent PCP specifically in patients with HIV.”

Strub noted that NIH ultimately issued the guidelines two years later after confirming through a drug trial that Bactrim did, indeed, effectively prevent PCP. But during the two years prior to the release of the guidelines, Callen estimated that nearly 17,000 people with AIDS died of PCP, Strub says in his book. He says Callen expressed outrage that many of them might have survived if their doctors were informed of the effectiveness of Bactrim as a preventive measure.

When contacted by the Blade last week, Fauci disputed Callen’s account of what happened, saying he made it clear to Callen during their 1987 meeting that he did not have the authority to issue guidelines on prescription drugs.

“So what actually happened is that Michael came to me and said you know there is this preliminary activity and some small trials that Bactrim works,” Fauci said. “Would you come out and make a guideline to say it should be used by everybody. And I said ‘Michael I can’t do that but what I can do is help design and make sure that the grantees that we fund do a clinical trial in Bactrim to prove or not that it was safe and effective,’” he said.

“So I did exactly what I promised Michael,” Fauci said. “It took obviously longer than he would have wished. But I didn’t blow him off and say I don’t want to issue guidelines. The fact is that’s neither within my purview nor within the responsibility or authority I have to issue guidelines.”

In 1990, Strub ran for Congress in a district just north of New York City where he had been living while operating a fundraising business. Although he lost in the Democratic primary, many familiar with his race said he broke new ground by becoming the first openly HIV-positive candidate to run for a federal office.

Four years later, in 1994, he founded POZ magazine, a first-of-its-kind upscale publication reporting on the experiences of people with HIV and the trials and tribulations they faced – including Strub himself – in struggling to stay alive.

By that time Strub was out publicly, was a veteran of AIDS protests, and had experienced several years earlier the death of his first partner from AIDS.

In keeping with the belief at the time that nearly everyone with AIDS would die, Strub raised the bulk of the capital needed to launch POZ by selling two life insurance policies he had to a “viatical” investment company for $345,000.

The company expected to yield $75,000 in profit by cashing in the $450,000 combined value of the two policies when Strub died.

Although Strub survived, he tells in great detail how during the years immediately following the launching of POZ, he struggled with Kaposi’s sarcoma and pneumocystis pneumonia. His says his decision to discontinue treatment with the harsh drug AZT, which had side effects that caused fellow patients to become sick and weak, most likely kept him alive long enough to be saved by the new generation of protease inhibitor drugs.

In 2004 Strub sold POZ and began spending more time at his home in the small town of Milford, Penn., while retaining his home in Manhattan.

Following are excerpts of the Blade’s interview with Strub.

Washington Blade: What prompted you to write the book at this time?

Sean Strub: I had thought about it over the years and I kind of resisted it in the years after I left POZ. Then about five years ago enough time had passed from the very worst days that I thought I was getting more perspective on it. I felt more of a sense of wanting to remember people and I think most importantly to document a history that had not been well documented.

And there are fewer and fewer people who are around to tell the story firsthand who were really on the front lines over such a long period of time.

Blade: You describe in a moving way in your book how sick you were in the middle 1990s. You wrote that you expected to die. Why do you feel you survived long enough to benefit from the new generation of effective drugs such as protease inhibitors when others did not?

Strub: I think that is the question thousands of people who survived that time ask themselves often. I thought of it once as a sort of survivor’s guilt. But today it just seems like an existential question. It’s a question I don’t think I will ever answer but also one I don’t think I should ever stop asking.

The quality of care a person received is probably the most important factor, but there are others. When [the late New York AIDS activist] Michael Callen wrote “Surviving AIDS” in 1990 he recognized three shared traits amongst people with HIV at that time that were surviving. This was before combination treatment, of course. The three were, one, a belief that some people would survive; two, they could identify a reason to survive — raising a child, loving a partner, running a business, completing school, etc.; and, three, when asked how they treated their illness, they could list many different strategies. It wasn’t so much which strategy they pursued, but it was the length of the list that mattered because that indicated they were people who were seeking to survive. I think that is apt for me. I sought to survive…

Survival for me was a path, not a place. The bullet I narrowly missed was AZT mono-therapy. My doctor recommended it to me. Michael Callen constantly harangued me against it. I took it for a few weeks then stopped it. I believe if I had continued on AZT mono-therapy, I wouldn’t have survived to benefit from protease therapy.

Blade: To jump ahead a bit, what are you doing these days?

Strub: I’m the executive director of the Sero Project, which is a network of people and their allies fighting for freedom from stigma and injustice. And that’s our tagline. And we are particularly focused on HIV criminalization. So we have been engaged with a lot of the decriminalization advocates across the country.

Blade: You go into that in the last chapter of your book, saying in no uncertain terms that laws making it a crime for someone who is HIV positive to have sex with another person without telling them they are positive should be repealed.

Strub: You can see SeroProject.com. If you go to that website there is a little short film. It’s the trailer to a documentary I’ve been working on called HIV is Not a Crime. It really explains our work.

Blade: Wasn’t there a bill introduced in Maryland to increase the penalties for so-called intentional HIV transmission?

Strub: A couple of years ago – I think it was State Sen. [Norman R.] Stone [D-Baltimore County] who wanted to increase the maximum penalty from three years to 35 years. And that was beaten back. And then last year Del. Shirley Nathan Pulliam [D-Baltimore County] introduced a bill to get rid of the statute entirely.

In Maryland like every other state they have assault statutes and someone who maliciously intends to harm someone else they can prosecute, whether they use a gun or a baseball bat…And the HIV specific statute doesn’t contribute anything to public safety or public health. It hurts public health and it’s profoundly stigmatizing. So she introduced that bill last year. It’s been withdrawn.

Blade: Is it mostly states that have these statutes? Is there a federal statute?

Strub: There is not a federal statute. So it’s state by state. About two thirds of the states have these HIV specific statutes; although in every state they can use someone’s HIV-positive status inappropriately in some criminal prosecutions in heightened charges. In Texas and New York, for example, they don’t have HIV-specific statutes.

But there is a guy in Texas spending 35 years for spitting at a cop and a guy in New York who just got out of jail after serving six and a half years for spitting when a New York appeals court ruled that in New York State saliva cannot be considered a deadly weapon. So the specific statutes are in about two thirds of the states.

At the federal level we did just get through Congress recently an amendment to the Armed Services Appropriations bill to have the Secretary of Defense have a review of the Uniform Code of Military Justice and how it relates to HIV to make sure that their policies and procedures are consistent with contemporary science and not inappropriately stigmatizing people. So that’s our only legislative victory so far on this. There will be more to come. We’re organizing in individual states and I hope there will be some pretty good action in a couple of them this year.

Blade: So is this your main activity at this point?

Strub: That’s correct – that and here in Milford [Pa.] I also co-own a historic hotel-restaurant called the Hotel Fauchere. So that’s my sort of business here. But I spend most of my time on the advocacy work.

Blade: Are you in Milford, Pennsylvania right now?

Strub: I’m in Milford at the moment. I live in Milford and also in Manhattan. But lately, for a year or so, I’ve been much more in Milford than in New York.

Blade: That seems to be the type of thing you have done throughout your professional career – a combination of activism and as you called it entrepreneurial activity. Would that be correct?

Strub: That’s correct.

Blade: Do you have any interest in going back into the direct mail and fundraising field?

Strub: Not really – I’m always, I’m frequently giving pro-bono counsel to the efforts I support around fundraising. But I’ve really been much more focused on the advocacy work, particularly recreating a grass roots network of people with HIV engaged in advocacy on the state and local level, which we had in the ‘80s and even in the early ‘90s and then it kind of dissipated through the ‘90s. And now it’s enjoying a bit of a revival. We are recreating these networks of people with HIV.

Blade: What is your assessment of the status of the national AIDS advocacy organizations right now? Some people have referred to them as AIDS incorporated. Some people say they have overlapping functions and maybe there is duplication of efforts and there should be more consolidation.

Strub: Well, this AIDS, Inc. phrase is often used in a pejorative way. But it’s also just descriptive. It’s a big industry now. Careers are made – institutions – it isn’t the epidemic of 30 years ago by any means – and thank goodness. But in terms of the advocacy organizations, I don’t really see the advocacy organizations at the federal level…

HRC was pretty consistent in terms of advocating for the Ryan White program in some of the big funding streams. But the other issues outside of funding for service providers, for example, the issues involving privacy, confidentiality, stigma, patient autonomy, criminalization and the whole range of human rights approaches to the epidemic became an orphan in Washington and no one was really working on those.

Now what has happened in the last several years…there is sort of a growing pressure on the national LGBT groups to re-engage in the epidemic. After combination therapy came out – first of all, a lot of advocates left AIDS work because a lot of them were personally concerned about – their engagement and advocacy was due to their own fear, right? And their AIDS activism was a singular effort. It wasn’t connected to any broader social justice movement. And so a lot of those people kind of left after combination therapy came out.

And a lot of the LGBT groups turned to other opportunities and exciting things – ‘Don’t ask, Don’t Tell’ repeal and marriage equality and so on. And all of these human rights-related issues kind of got neglected. And so then we end up with things like criminalization.

Now, that is a growing and scary phenomenon that leaves every person with HIV in the country just one disgruntled, ex-partner away from being in a courtroom.

And yet the survey work has shown that gay men overwhelmingly support having it be a criminal act for someone with HIV not to disclose that fact prior to being intimate, independent of whether there is any risk involved and independent of whether there is any HIV transmission involved.

So we’re kind of playing catch up in the gay community on these issues. There are good things happening. I think HRC is certain to focus on this. They’ve been quite receptive toward us and some other groups. So I think we’re going to see more advocacy from gay groups.

Blade: What about the issue of prevention and what is possible? The issue of sex is always with us. Frank Kameny, the veteran gay rights pioneer, said back when the epidemic began and we learned the virus was sexually transmitted that you can never change the sex urge.

Strub: Well, even in the worst years when people were presumably the most frightened we never got much more than half of gay men to consistently use condoms. So there definitely is a limit on how far that will go. But I’m also not a fan of just relying on the biomedical approaches.

I think in terms of prevention the things we need to do – first we need to target prevention funding. Two-thirds of the new cases are among gay men. Only a small percentage of federal prevention funds are targeted to men who have sex with men…

That’s one thing. Second, there still is a reluctance to talk honestly about how gay men have sex. And this goes back to the first days of the epidemic. I write about that in New York – the conflict between the AIDS establishment and [AIDS activists] Michael Callen, Richard Berkowitz and [AIDS doctor and researcher] Joe Sonnabend. Too much of the prevention messaging is either fear based, which is sort of relying on what might have been effective in the epidemic 25 years ago. But the truth is the consequences of HIV infection today are very different than they were 25 years ago. And you can’t use tactics and strategies that worked for that epidemic and expect them to work for this epidemic. You need to deal with the epidemic we have today and the realities of that today…

The New York City Health Department has this one ad that centers on HIV and the next minute you’ve got a brain fog and anal cancer and your bones are snapping. And all of those things can be side effects of the treatments. And I’m not saying they don’t happen. They do happen. I’ve said a lot about the side effects. But they aren’t happening to everybody. And to gay men they know this is a wild exaggeration. I compare it to the anti-drug campaign that sort of implies that if you smoke a joint and two weeks later you’re going to be starting heroin. People know better than that.

And we’re not focusing on getting people real practical information for them to integrate into their own risk reduction analysis, which is what I think most gay men and most people do before they have sex with someone they don’t know a lot about.

We need to give people the information so that they are doing that risk analysis. We need prevention campaigns that are fact based, that are non-judgmental, and that are supportive of gay male sexuality.

You know, Joe Sonnabend said early in the epidemic and I quoted him in the book, he said we’ll never defeat AIDS until we treat the anus as a sex organ with the same respect given to the vagina or the penis. And that remains true today.

Blade: You mentioned that Dr. Anthony Fauci appeared to be an impediment to the use of the drug Bactrim back in 1987 as a prophylaxis to prevent pneumocystis pneumonia for people with AIDS.

Strub: Absolutely.

Blade: Did he have what he might consider legitimate reasons for needing more time to promote this drug?

Strub: Well I don’t know what he would say. It was written about at the time. Michael Callen referred to it as one of the most egregious examples of federal indifference to the lives of gay men. At the time Michael met with him in 1987 and begged him to support publicizing and making this a recommendation because Bactrim… was around a long time and was very effective. It has been used in immune compromised patients before. There were even clinical trials done in transplant patients. So there was a fair amount of literature on its use by immune compromised patients to prevent PCP [pneumocystis carinii pneumonia].

So Callen went and met with Fauci and Fauci was doubtful. He wanted clinical trials done to prove it…So when the trial results were in that’s when the feds came out with the recommendation around Bactrim. And in that intervening period – I have the number in there — something like 12 or 14 or 16,000 people with AIDS died of pneumocystis, which is a horrible death. You probably know people who died of it. They suffocate to death.

And if they had been on this treatment the majority of them would not have died of pneumocystis. They may or may not have lived until combination therapy came up. Who knows? Some of them surely would have. You know I don’t get into personally bashing Fauci. But this is kind of an example indicative of the federal response then and to a certain extent today and how all sorts of bureaucracy and funding get in the way of what is effective and needed.

Blade: Going back to your years in Washington you name certain members of Congress as being gay. Do you ‘out’ some of these people or were they known publicly to be gay?

Strub: The people I talk about I knew before they were outed. I talked about [former Rep.] Gerry Studds [D-Mass.]. I talked about [former Rep.] Barney [Frank (D-Mass)]. I think I referenced [former Rep.] Peter Kostmayer [D-Penn.]. I talked about the Bob Bauman scandal [former Rep. Robert Bauman (R-Md.)]. I referenced [former Rep.] Stuart McKinney [(R-Conn.)]. I don’t think I’m outing any current or former member of Congress that isn’t already known to be gay.

Blade: You appear to be more than a little critical of the Clinton administration on the AIDS front.

Strub: I thought I went easy on him.

Blade: Richard Socarides, Clinton’s White House liaison to the LGBT community, may disagree with some of the things you say in the book about Clinton.

Strub: Well, Richard Socarides – there are a lot of people who will disagree with Richard Socarides’ version of that history. I tried not to take things personally because there is always another side. But the indifference and the opportunism and the manipulation of the issue for political purposes are something I and a lot of other people saw really clearly – really visibly. And there is no question about it. The needle exchange stuff. You know, that’s a sin right up there with Fauci on the Bactrim. That is something that was so immediate, so clear.

One of the biggest reasons that the heterosexual transmission in New York has declined so precipitously is because of needle exchange.

Blade: Would the Clinton people argue that they didn’t have the political support in Congress and elsewhere to fund and promote needle exchange?

Strub: That’s always the argument – that’s always the argument. But you know that’s also a decision. The other way of saying it is they weren’t willing to expend the political capital to do that. And that becomes a little chicken and egg-ish, right? They could have done it. They could have gotten it done. There would have been some price they would have had to pay. Maybe it would have screwed up the rest of their legislative agenda. I don’t know. And I suppose they could have tried and ended up failing. But I think if the president had shown the leadership on it I think it would have happened because the science was so clear.

Blade: Didn’t at some point Congress enact into law a funding ban on needle exchange programs?

Strub: Sure. But that isn’t a reason for the Clinton administration not to have sought to change it. There are many different strategies. The problem was they decided to roll over on it. They were not going to go out on a limb on this issue and to bring about a change was not that important to them. You can say they had other priorities. Everyone in office only has so much political capital and they have to use it on what’s important to them. And we learned that this was not something that was important to them.

Blade: What can you say about the status of your marriage to a woman friend Doris O’Donnell that you tell about in the book? You said the marriage, among other things, would have allowed her to obtain your disability benefits and pass them on to your life partner Xavier Morales in the event of your death. Are you still married to her?

Strub: No. We got married. And then when my health came back and she had qualified for Medicare and Social Security we then got divorced because for tax reasons it made sense. She subsequently has died.

Blade: I’m sorry to hear that.

Strub: She was quite elderly. She used to joke that when we got married the only good reason to get married was for money. Her parents were both journalists. Her father was the Washington bureau chief for the Daily News for decades – John O’Donnell. And her mother was Doris Fleeson, who was the first female political columnist who was syndicated and was very close friends with Eleanor Roosevelt. I think her columns started in the 1940s and went right up into the 1960s. She was in a hundred and some papers. Mary McGrory was her protégé. So that’s just an aside but she grew up in that Washington media political world.

Blade: You mention in the book that your partner Xavier was not all that pleased about your decision to get married to a woman. Is he still part of your life now?

Strub: He’s roasting a chicken in the other room. After my health came back – there was a real stress on my relationship as this is for a lot of people. For most of the time we were together – it was usually unspoken – but the assumption was I was going to die and he would go on with his life. And he had moved in with me and then I got sick. And after my health got better there were stresses on the relationship and we broke up for a while and a number of years ago we got back together. We’re now [together] 22 years believe it or not.

Books

New book offers observations on race, beauty, love

‘How to Live Free in a Dangerous World’ is a journey of discovery

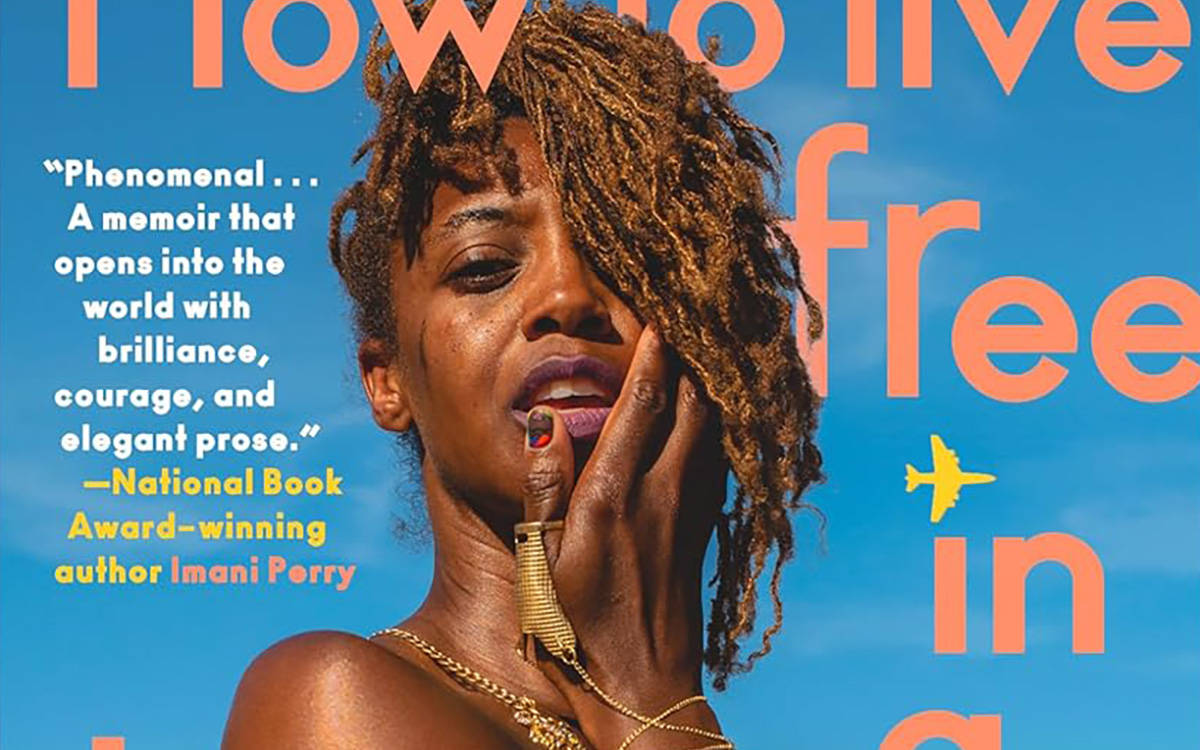

‘How to Live Free in a Dangerous World: A Decolonial Memoir’

By Shayla Lawson

c.2024, Tiny Reparations Books

$29/320 pages

Do you really need three pairs of shoes?

The answer is probably yes: you can’t dance in hikers, you can’t shop in stilettos, you can’t hike in clogs. So what else do you overpack on this long-awaited trip? Extra shorts, extra tees, you can’t have enough things to wear. And in the new book “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” by Shayla Lawson, you’ll need to bring your curiosity.

Minneapolis has always been one of their favorite cities, perhaps because Shayla Lawson was at one of Prince’s first concerts. They weren’t born yet; they were there in their mother’s womb and it was the first of many concerts.

In all their travels, Lawson has noticed that “being a Black American” has its benefits. People in other countries seem to hold Black Americans in higher esteem than do people in America. Still, there’s racism – for instance, their husband’s family celebrates Christmas in blackface.

Yes, Lawson was married to a Dutch man they met in Harlem. “Not Haarlem,” Lawson is quick to point out, and after the wedding, they became a housewife, learned the language of their husband, and fell in love with his grandmother. Alas, he cheated on them and the marriage didn’t last. He gave them a dog, which loved them more than the man ever did.

They’ve been to Spain, and saw a tagline in which a dark-skinned Earth Mother was created. Said Lawson, “I find it ironic, to be ordained a deity when it’s been a … journey to be treated like a person.”

They’ve fallen in love with “middle-American drag: it’s the glitteriest because our mothers are the prettiest.” They changed their pronouns after a struggle “to define my identity,” pointing out that in many languages, pronouns are “genderless.” They looked upon Frida Kahlo in Mexico, and thought about their own disability. And they wish you a good trip, wherever you’re going.

“No matter where you are,” says Lawson, “may you always be certain who you are. And when you are, get everything you deserve.”

Crack open the front cover of “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” and you might wonder what the heck you just got yourself into. The first chapter is artsy, painted with watercolors, and difficult to peg. Stick around, though. It gets better.

Past that opening, author Shayna Lawson takes readers on a not-so-little trip, both world-wide and with observant eyes – although it seems, at times, that the former is secondary to that which Lawson sees. Readers won’t mind that so much; the observations on race, beauty, love, the attitudes of others toward America, and finding one’s best life are really what takes the wheel in this memoir anyhow. Reading this book, therefore, is not so much a vacation as it is a journey of discovery and joy.

Just be willing to keep reading, that’s all you need to know to get the most out of this book. Stick around and “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” is what to pack.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Story of paralysis and survival features queer characters

‘Unswerving: A Novel’ opens your eyes and makes you think

‘Unswerving: A Novel’

By Barbara Ridley

c.2024, University of Wisconsin Press

$19.95 / 227 pages

It happened in a heartbeat.

A split-second, a half a breath, that’s all it took. It was so quick, so sharp-edged that you can almost draw a line between before and after, between then and now. Will anything ever be the same again? Perhaps, but maybe not. As in the new book “Unswerving” by Barbara Ridley, things change, and so might you.

She could remember lines, hypnotizing yellow ones spaced on a road, and her partner, Les, asleep in the seat beside her. It was all so hazy. Everything Tave Greenwich could recall before she woke up in a hospital bed felt like a dream.

It was as though she’d lost a month of her life.

“Life,” if you even wanted to call it that, which she didn’t. Tave’s hands resembled claws bent at the wrist. Before the accident, she was a talented softball catcher but now she could barely get her arms to raise above her shoulders. She could hear her stomach gurgle, but she couldn’t feel it. Paralyzed from the chest down, Tave had to have help with even the most basic care.

She was told that she could learn some skills again, if she worked hard. She was told that she’d leave rehab some day soon. What nobody told her was how Les, Leslie, her partner, girlfriend, love, was doing after the accident.

Physical therapist Beth Farringdon was reminded time and again not to get over-involved with her patients, but she saw something in Tave that she couldn’t ignore. Beth was on the board of directors of a group that sponsored sporting events for disabled athletes; she knew people who could serve as role models for Tave, and she knew that all this could ease Tave’s adjustment into her new life. It was probably not entirely in her job description, but Beth couldn’t stop thinking of ways to help Tave who, at 23, was practically a baby.

She could, for instance, take Tave on outings or help find Les – even though it made Beth’s own girlfriend, Katy, jealous.

So, here’s a little something to know before you start reading “Unswerving”: author Barbara Ridley is a former nurse-practitioner who used to care for patients with spinal cord injuries. That should give readers a comfortable sense of satisfaction, knowing that her experiences give this novel an authenticity that feels right and rings true, no faking.

But that’s not the only appeal of this book: while there are a few minor things that might have readers shaking their heads (HIPAA, anyone?), Ridley’s characters are mostly lifelike and mostly likable. Even the nasties are well done and the mysterious character that’s there-not-there boosts the appeal. Put everyone together, twist a little bit to the left, give them some plotlines that can’t ruined by early guessing, and you’ve got a quick-read novel that you can enjoy and feel good about sharing.

And share you will because this is a book that may also open a few eyes and make readers think. Start “Unswerving” and you’ll (heart) it.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Examining importance of queer places in history of arts and culture

‘Nothing Ever Just Disappears’ shines with grace and lyrical prose

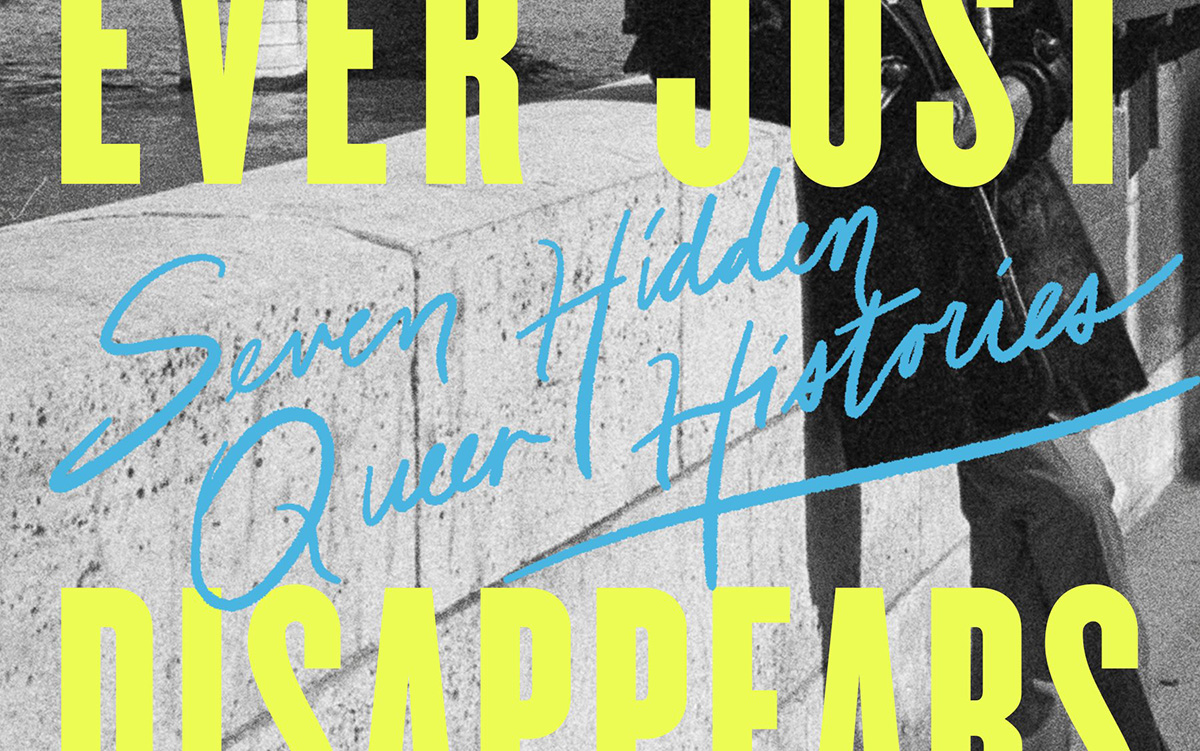

‘Nothing Ever Just Disappears: Seven Hidden Queer Histories’

By Diarmuid Hester

c.2024, Pegasus Books

$29.95/358 pages

Go to your spot.

Where that is comes to mind immediately: a palatial home with soaring windows, or a humble cabin in a glen, a ramshackle treehouse, a window seat, a coffeehouse table, or just a bed with a special blanket. It’s the place where your mind unspools and creativity surges, where you relax, process, and think. It’s the spot where, as in the new book “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” by Diarmuid Hester, you belong.

Clinging “to a spit of land on the south-east coast of England” is Prospect Cottage, where artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman lived until he died of AIDS in 1994. It’s a simple four-room place, but it was important to him. Not long ago, Hester visited Prospect Cottage to “examine the importance of queer places in the history of arts and culture.”

So many “queer spaces” are disappearing. Still, we can talk about those that aren’t.

In his classic book, “Maurice,” writer E.M. Forster imagined the lives of two men who loved one another but could never be together, and their romantic meeting near a second-floor window. The novel, when finished, “proved too radical even for Forster himself.” He didn’t “allow” its publication until after he was dead.

“Patriarchal power,” says Hester, largely controlled who was able to occupy certain spots in London at the turn of the last century. Still, “queer suffragettes” there managed to leave their mark: women like Vera Holme, chauffeur to suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst; writer Virginia Woolf; newspaperwoman Edith Craig, and others who “made enormous contributions to the cause.”

Josephine Baker grew up in poverty, learning to dance to keep warm, but she had Paris, the city that “made her into a star.” Artist and “transgender icon” Claude Cahun loved Jersey, the place where she worked to “show just how much gender is masquerade.” Writer James Baldwin felt most at home in a small town in France. B-filmmaker Jack Smith embraced New York – and vice versa. And on a personal journey, Hester mourns his friend, artist Kevin Killian, who lived and died in his beloved San Francisco.

Juxtaposing place and person, “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” features an interesting way of presenting the idea that both are intertwined deeper than it may seem at first glance. The point is made with grace and lyrical prose, in a storyteller’s manner that offers back story and history as author Diarmuid Hester bemoans the loss of “queer spaces.” This is really a lovely, meaningful book – though readers may argue the points made as they pass through the places included here. Landscapes change with history all the time; don’t modern “queer spaces” count?

That’s a fair question to ask, one that could bring these “hidden” histories full-circle: We often preserve important monuments from history. In memorializing the actions of the queer artists who’ve worked for the future, the places that inspired them are worth enshrining, too.

Reading this book may be the most relaxing, soothing thing you’ll do this month. Try “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” because it really hits the spot.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

Africa5 days ago

Africa5 days agoCongolese lawmaker introduces anti-homosexuality bill

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoReenactment of first gay rights picket at White House draws interest of tourists

-

District of Columbia1 day ago

District of Columbia1 day agoNew D.C. LGBTQ+ bar Crush set to open April 19

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoOut in the World: LGBTQ news from Europe and Asia