Arts & Entertainment

Remembering the queer voices and allies we lost in 2019

Authors, artists and others who changed the world

Many acclaimed LGBTQ people and allies died in 2019. They include:

Carol Channing, the legendary Broadway actress, died on Jan. 15 at age 97 in Rancho Mirage, Calif. She was best know for her performances as Lorelei Lee in “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” and Dolly Gallagher Levi in “Hello Dolly!”

Mary Oliver, a lesbian poet, died on Jan. 17 at her Florida home at age 83. Her collection “American Primitive, won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize.

Harris Wofford, a Democratic senator and civil rights crusader, died on Jan. 21 at age 92. After his wife died, Wofford fell in love with Matthew Charlton. They married in 2018.

Barbra Siperstein, a transgender rights crusader died on Feb. 3 at age 76 from cancer at a New Brunswick, N.J. hospital. A New Jersey law bears her name. It permits people in New Jersey to change their gender on their birth certificates without having to prove they’ve had surgery.

Patricia Nell Warren, author of the 1974 novel “The Front Runner” died on Feb. 9 at age 82 in Santa Monica, Calif. from lung cancer. The iconic book was one of the first to feature an open same-sex male relationship.

Hilde Zadek, a Vienna State Opera mainstay, died on Feb. 21 at 101 in Karlsruhe, Germany. She debuted in the title role of in Verdi’s “Aida” in 1947. She retired in 1971.

Jackie Shane, a black transgender soul singer who received a 2018 Grammy nomination for best historical album for her album “Any Other Way,” died at age 78 in Nashville. Her body was found at her home on Feb. 21.

Gillian Freeman, the British novelist who wrote the 1961 novel “The Leather Boys” died on Feb. 23 at age 89 in London. The book was one of the first to portray working-class gay characters.

Carrie Ann Lucas, a queer lawyer and disability rights advocate, died on Feb. 24 at age 47 in Loveland, Colo. She championed the rights of disabled parents.

John Richardson, an art historian renowned for his four-volume biography of Pablo Picasso, died at age 95 on March 12 at his Manhattan home.

Barbara Hammer, a lesbian filmmaker, died at age 79 from ovarian cancer at her partner Florrie Burke’s home in Manhattan on March 16. Hammer celebrated lesbian sexuality in “Dyketactics” and other films.

Dr. Richard Green, a psychiatrist, died at age 82 on April 6 at his London home. He was one of the first to critique the idea that being queer is a psychiatric disorder.

Michael Fesco, the nightclub owner who provided open spaces (Ice Palace, Flamingo and other venues) for gay men to dance when LGBTQ people couldn’t be out, died on April 12 at age 84 in Palm Springs, Calif.

Lyra McKee, a 29-year-old, queer Northern Ireland journalist, died on April 18. She was killed while covering violence in Londonderry.

Giuliano Bugialli, a gay culinary historian and three-time James Beard Award winner, died at age 88 on April 26 in Viareggio, Italy.

Doris Day, queer icon, actress and singer best known for her romantic comedies with Rock Hudson, died at age 97 on May 13 at her Carmel Valley, Calif. home from pneumonia.

Binyavanga Wainaina, a Kenyan author, founder of the magazine “Kwani?” and one of the first prominent African writers to come out as gay, died at age 48 on May 21 in a Nairobi hospital.

Charles A. Reich, author of the 1970 counter-culture manifesto “The Greening of America,” died on June 15 at age 91 in San Francisco.

Douglas Crimp, an art critic and AIDS activist, died on July 5 at age 74 at his Manhattan home from multiple myeloma. He wrote many articles for journals. Yet he also attended meetings of the AIDS group ACT UP.

Elka Gilmore, a queer chef known for her fusion cuisine, died at age 59 on July 6 in San Francisco. The New York Times Magazine called her “the enfant terrible of the modern California kitchen.”

George Hodgman, a gay editor, died on July 19 at age 60 at his Manhattan home. The cause was thought to be suicide. Hodgman’s memoir “Bettyville” is his story of staying in Paris, Mo. with his widowed mother who had dementia.

Lee Bennett Hopkins, a gay poet who wrote and edited many books for children, died on Aug. 8 at age 81 in Cape Coral, Fla. In 2018, he edited “World Make Way: New Poems Inspired by Art from The Metropolitan Museum.”

Sally Floyd, one of the inventors of Random Early Detection (RED), a widely used internet algorithm, died at age 69 on Aug. 25 at her Berkeley, Calif. home from cancer. She is survived by her wife Carole Leita.

Valerie Harper, the actress best known as Rhoda Morgenstern on “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” died on Aug. 30 at age 80 from cancer. Harper was D.C.’s 2009 Capital Pride Parade grand marshal.

Rip Taylor, a gay comedian known as The King of Confetti, died on Oct. 6 at age 88 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

John Giorno, a gay artist, died on Oct. 11 at his home in Manhattan at age 82. In 1969, he founded Dial-A-Poem, a communications system enabling people to hear Allen Ginsberg and other poets read their poems.

Gillian Jagger, an artist whose work (installations of animal carcasses and tree trunks) wasn’t aligned with any one movement, died on Oct. 21 in Ellenville, N.Y. at age 88. “I felt that nature held the truth I wanted,” she told the U.K’s Public Monuments and Sculpture Association magazine. She is survived by her wife Connie Mander.

Howard Cruse, a gay cartoonist whose comic strip “Wendel” ran in The Advocate for several years, died on Nov. 26 at age 75 in Pittsfield, Mass. from lymphoma. His graphic novel “Stuck Rubber Baby” and other work influenced other queer cartoonists. He is survived by his husband Ed Sedarbaum.

Michael Howard, a gay military historian and decorated combat veteran and pioneer of the “English school” of strategic studies, died on Nov. 30 in Swindon, England at age 97.

Shelley Morrison, who played Rosario on “Will and Grace” from 1999 to 2006, died on Dec. 1 in Los Angeles at age 83 from heart failure.

William Luce, who wrote the acclaimed plays “The Belle of Amherst” about Emily Dickinson and “Barrymore” about John Barrymore, died on Dec. 9 at a memory-care facility in Green Valley, Ariz. at age 88. Ray Lewis, his partner of 50 years, died in 2001.

Books

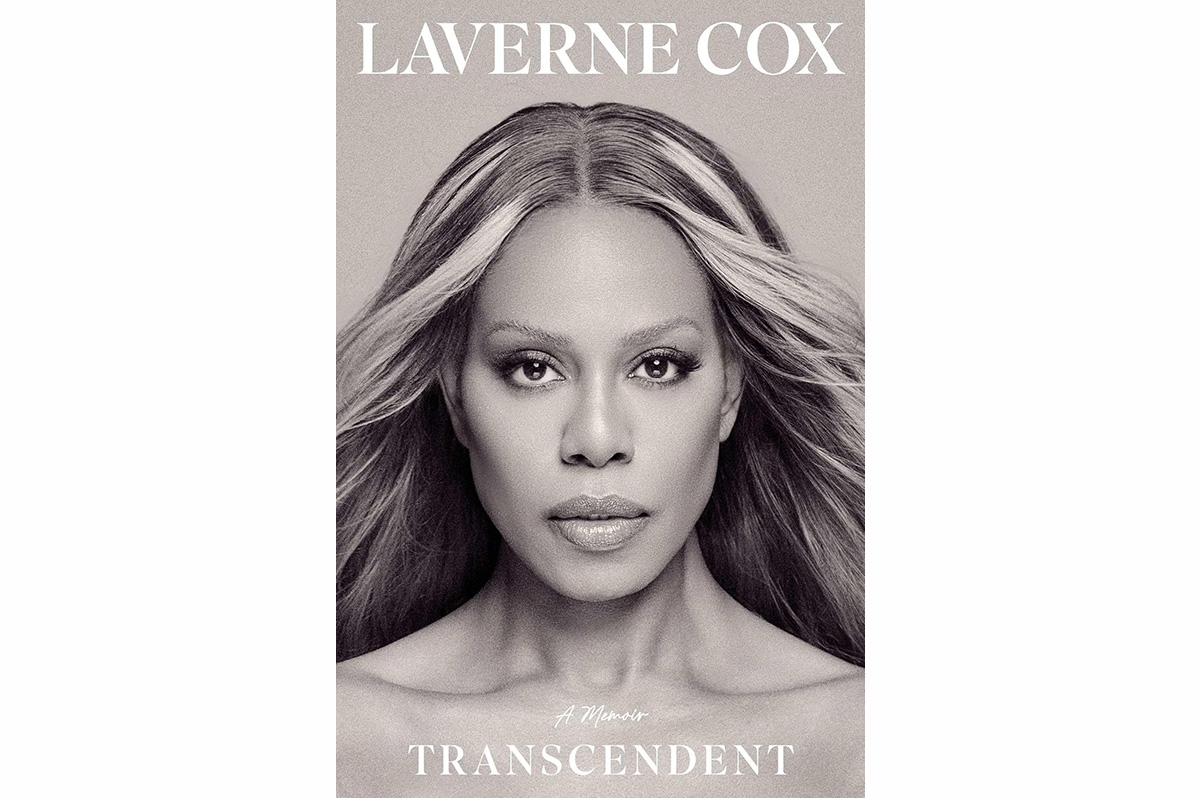

Laverne Cox, Liza Minnelli among authors with new books

A tome for every taste this reading season

Spring is a great time to think about vacations, spring break, lunch on the patio, or an afternoon in the park. You’ll want to bring one (or all!) of these great new books.

So let’s start here: What are you up for? How about a great new novel?

If you’re a mystery fan, you’ll want to make reservations to visit “Disaster Gay Detective Agency” by Lev AC Rosen (Poisoned Pen Press, June 2). It’s a whodunit featuring a group of gay roommates, one of whom is a swoony romantic. Add a mysterious man who disappears and a murder, of course, and you’ve got the novel you need for the beach.

Don’t discount young adult books, if you want something light to read this spring. “What Happened to Those Girls” by Carlyn Greenwald (Sourcebooks Fire, June 30) is a thriller about mean girls and a camping trip that goes terribly, bloodily wrong. Meant for teens ages 14 and up, young adult books are breezier and lighter fare for the busy grown-up reader.

If you loved “Boyfriend Material” and “Husband Material,” you’ll be eager for the next installment from author Alexis Hall. “Father Material” (Sourcebooks Casablanca, June 2) takes Luc and Oliver to the next step. First was dating. Then was marriage. Is it time for the sound of pitter-patter on the kitchen floor?

Maybe something even lighter? Then how about a book of essays – like “The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Gay” bycomedian and writer Eliot Glazer (Gallery Books, Aug. 11). It’s a book of essays on being gay today, the irritations, the joys, and fitting in. Be aware that these essays may contain a bit of spice – but isn’t that what you want for your reading pleasure anyhow, hmmm?

But okay, let’s say you want something with a little more heft to it. How about a biography?

Look for “Transcendant” by Laverne Cox (Gallery Books, June 9), or “Kids, Wait Till You Hear This” by Liza Minnelli (Grand Central Publishing, March 10), and “Every Inch a Lady” by Audrey Smaltz with Alina Mitchell (Amistad, July 14). Keep your eyes open for “Without Prejudice: My Life as a Gay Judge” by Harvey Brownstone (ECW Press, May 26) or “The Double Dutch Fuss” by Phill Branch (Amistad, June 2).

Then again, maybe you want some history, or something different.

So here: look for “Queer Saints: A Radical Guide to Magic, Miracles, and Modern Intercession” by Antonio Pagliarulo (Weiser, June 1) for a little bit of faith-based gay. Music lovers will want “Mighty Real: A History of LGBTQ Music, 1969-2000” by Barry Walters (Viking, May 12). Activists will want “In the Arms of Mountains: A Memoir of Land, Love, and Queer Resistance in Red America” byformer Idaho state Sen. Cole Nicole LeFavour (Beacon Press, May 26).

And if these books aren’t enough, then be sure to check with your favorite bookseller or librarian. They’ll have exactly what you’re in the mood to read. They’ll find what you need for that patio, beach towel, or easy chair.

Music & Concerts

Gaga, Cardi B, and more to grace D.C. stages this spring

Shake off your winter doldrums at a local concert

D.C. shakes off its winter blues this spring as the music scene pops off. We all know the big star is coming: Lady Gaga will perform at Capital One Arena on March 23. But plenty of other stars, big and small, will grace D.C. stages, including many LGBTQ and ally artists.

March

3/15, 9:30 Club, St. Lucia – Indie electronic music project known for its synth-pop sound, which blends ‘80s influences with electronic and indie rock elements.

3/31, Lincoln Theatre, Perfume Genius – Indie/pop singer/songwriter Mike Hadreas, also known as Perfume Genius, has toured with a full band, but he is stripping things back for this tour.

April

4/8, Capital One, Cardi B. Cardi B, from New York, unapologetic and proud, is the first solo female artist to win the Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. This year, she’s on her Little Miss Drama Tour, in support of her second studio album, “Am I the Drama?”

4/13, Lincoln Theatre, The Naked Magicians. Australia’s The Naked Magicians are two performers who deliver live magic and laughs while wearing nothing but a top hat and a smile.

4/18, Capital One, Florence and the Machine. Longstanding indie rock back from Great Britain, much-loved for lead singer Florence’s powerful vocals. On their Everybody Scream Tour.

4/16, Capital One, Demi Lovato. Singer/songwriter from Texas, who came out as nonbinary, is traveling on her “It’s Not That Deep Tour.”

4/21, The Anthem, Calum Scott. Platinum-selling gay singer/songwriter Calum Scott released his latest project, Avenoir, last year. Scott rose to fame in 2015 after competing on Britain’s Got Talent, where he performed a cover of Robyn’s hit “Dancing on My Own“.

4/26, Atlantis, Caroline Kingsbury. American queer pop musician from Los Angeles. She released her debut album in 2021, and has two additional EPs. She’s played Lollapalooza 2025 and All Things Go 2025, as well as gone on a co-headlining U.S. tour with MARIS. Shock Treatment is her latest EP.

4/26, Anthem, Raye. This bisexual artist, known for her current chart-topping “”Where Is My Husband!” single, blends pop, jazz, R&B, and more.

4/30, Union Stage, Daya. This bisexual singer/songwriter is on her “Til Every Petal Drops Tour,” touring the album of the same name that was released last year.

May

5/1, The Anthem, Joost Klein. Eurovision comes to D.C. in Joost Klein: Originally a Youtuber, he was selected to represent the Netherlands at Eurovision in 2024 with his song “Europapa.” He released a new album on New Year’s Day.

5/1, Fillmore, MIKA. MIKA is on his Spinning Out Tour. Born in Beirut and raised in both Paris and London, MIKA sings in multiple languages and has co-hosted Eurovision.

5/7, 9:30 Club, COBRAH. Clara Christensen, is a Swedish singer, songwriter, record producer, and club queen, making electronic dance music.

5/19, Atlantis, Grace Ives. New York-born singer/songwriter, known for her high-energy synth/electronic, bedroom-pop-style music.

June

6/2, The Anthem, James Blake. English crooner got big from his self-titled debut album in 2011. He won two Grammys and just released his 7th album,Trying Times, in March.

It’s surely a sign of the times that this year’s spring preview of upcoming screen entertainment doesn’t hold nearly as much boldly out-and-proud queer content as we would like – but then again, there are only a small handful of noteworthy titles overall – especially on the big screen, where, just like any year, the top-grade content is being saved for summer.

Even so, we’ve managed to put together a list of the movies and shows on the horizon that offer a much-needed taste of the rainbow; a mix that includes returning favorites, “don’t-miss” events, and a few promising big screen crowd-pleasers, it should keep you occupied until the summer season brings a fresh new crop of (hopeful) blockbusters with it.

Scarpetta (Prime Video, March 11). Proving once again that she’s on a quest to accumulate more screen appearances than any other actor in history, Nicole Kidman returns for another star turn by way of this true-crime-ish mystery series, adapted from the bestselling “Kay Scarpetta” novels by lesbian author Patrica Cornwell, as a “brilliant and beautiful” forensic pathologist who uses her knowledge to solve murders. If that’s not enough to draw you in, her co-stars include fellow Oscar-winners Jamie Lee Curtis (as her feisty older sister) and Ariana DuBose (as her nosy lesbian niece), as well as Bobby Cannavale and Simon Baker.

It’s Dorothy! (Peacock, March 13). Filmmaker Jeffrey McHale first won our attention with his fun and insightful “Showgirls” documentary, and now he’s back with a look at perhaps the ultimate queer icon in popular culture: none other than Dorothy Gale, that Kansas farm girl who taught us all that “there’s no place like home” in L. Frank Baum’s classic novel “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” and its sequels – and of course, in a certain movie adaptation starring Judy Garland. Charting the journey of the fictional heroine across a century of cultural reiterations – on the page, the stage, the screen, and beyond – with a mix of archival material, artistic interpretations, and commentary from queer and queer-friendly voices such as John Waters, Rufus Wainwright, and Lena Waithe, it’s sure to be required viewing for every “Friend of Dorothy” – and all of their friends, too.

The 37th Annual GLAAD Media Awards (Hulu, March 21). Sure, it’s already happened and you already knew (or can find out with a few quick taps of your phone screen) who and what the winners were – but, hey, we already know that the Oscars aren’t going to offer much in the way of queer victories (since there are only a small handful of queer nominees), so why not plan to watch the GLAAD ceremony (recorded live on March 5 for later streaming)?

The Comeback: Season 3 (HBO Max, March 22). Another returning gem is this inventive “mockumentary” style sitcom-about-a-sitcom, starring Lisa Kudrow as a “B-list” television star trying to revive her own faltering career. Slow to catch on in its first season (which originally aired in 2005), it won acclaim (and new fans) when it was rebooted in 2014 by Kudrow and collaborator/co-creator Michael Patrick King (former executive producer of “Sex in the City,” and now returns after a 12-year hiatus for another installment, which tracks “never-was” has-been Valerie Cherish through yet another attempt to make stardom happen. If you like cynical, sharp-edged satire, especially when it’s aimed at the behind-the-scenes world of show-biz, then you’ve probably already discovered this one – but if you haven’t, now’s your chance to jump on board.

Heartbreak High: Season 3 (Netflix, March 25). Fans of this imported Australian teen “dramedy” series – itself the “soft reboot” of another popular Australian series from the ‘90s – will be thrilled for the arrival of its third and final installment, which picks up where it left off in the lives (and sex lives) of the students and teachers of a suburban high school. As always, it can be expected to push the envelope (and some buttons) with its irreverent treatment of issues of class, race, and sexuality – and to deliver another season’s worth of the colorful and striking costume designs that have been acclaimed as a highlight of the show. And yes, it includes a refreshingly significant number of variously queer characters, so if you’re not already on board with his hidden gem of a streamer, we suggest you should give it a shot – you can probably even catch up on the first two seasons before this one drops.

Pretty Lethal (Prime Video, March 25). Fresh from a March 13 debut at the SXSW Film and TV Festival, this girl-power fueled action thriller from director Vicky Jewson and writer Kate Freund centers on a troupe of ballerinas who, while en route to a prestigious ballet competition, are stranded by a bus breakdown and must take shelter at a remote roadside inn run by Uma Thurman as a ruthless crime boss. Needless to say, the girls are forced to adapt their dance prowess into combat skills before the night is over. With a cast that includes Maddie Ziegler, Lana Condor, Avantika, Millicent Simonds, and Michael Culkin, our bet is that it’s sure to be campy fun with a feminist twist.

Forbidden Fruits (Theaters, March 27). Adapted from the play “Of the woman came the beginning of sin, and through her we all die” by Lily Houghton (who co-wrote the screenplay with director Meredith Alloway), this comedy/horror film about a group of young witches who operate a “femme cult” out of the basement of a mall store called “Free Eden” looks like another campy treat, full of witchy wiles and bitchy rivalries, but something about its theatrical pedigree tells us it will also be more than that. Even if we’re wrong, though, we’ll be perfectly happy; why would anyone say no to a delicious piece of camp, especially when it has a cast led by Lili Reinhart, Lola Tung, Victoria Pedretti, and Alexandra Shipp, with creator/influencer Emma Chamberlain in her film debut and heavyweight talent Gabrielle Union thrown in for good measure? We’re ready to join the coven.

Club Cumming (WOW Presents Plus, March 30). Queer icon Alan Cumming (currently riding high as host of “The Traitors”) takes us inside his NYC East Village gay bar, nightclub, and showplace for a behind-the-scenes reality series that spotlights the talent, fashion, and fabulously queer vibe that makes the establishment one of queer New York’s most iconic nightspots. Cabaret singer Daphne Always, go-go dancer and drag performer Michelle Wynters, Drag queen Brini Maxwell, Drag king Cunning Stunt, and Comedian Jake Cornell are among the many reasons why this little slice of the queer New York scene is reason enough alone to become a subscriber to World of Wonder’s streaming platform – though if you’re a “Drag Race” superfan, chances are good you already are.

The Boys: Season 5 (Prime Video, April 8). Amazon’s violent superhero satire, complete with its divisive and deliciously challenging emphasis on queer storylines and its in-your-face caricature of contemporary American “culture war” politics, returns for its fifth and final season, along with all the thorny issues of racism, nationalism, and xenophobia it has showcased all along, and an ensemble cast that includes Karl Urban, Jack Quaid, Antony Starr, Erin Moriarty, and the rest of the usual players. A decidedly queer-informed game-changer in the mainstream fan culture, it’s a show that will be sorely missed – but with several spin-offs already in existence (including the even-queerer “Gen V”) and another (“Vought Rising”) on the way, we can take comfort in knowing that its influence will live on.

Euphoria: Season 3 (HBO Max, April 12). The controversial Sam Levinson-created drama that is HBO’s fourth most-watched series of all time is back after a lengthy hiatus, rejoining the lives of its dysfunctional characters – queer struggling addict Rue (Zendaya), trans teen Jules (Hunter Schafer), abusive sexually insecure football star Nate (Jacob Elordi), and the rest – a full five years later, away from the social traumas of high school and settled into what we can only assume is an equally-dysfunctional life as young adults. Renowned for its cinematic visual styling and its no-holds-barred treatment of “triggering” subject matter, this long-awaited return is likely to be at or near the top of a lot of watchlists – and ours is no exception.

Mother Mary (Theaters, April 17). One of the most promising (and queerest) offerings of the season is this psychological thriller set in the world of pop music, helmed by acclaimed filmmaker David Lowery (“A Ghost Story,” “The Green Knight”) and starring Anne Hathaway (“The Devil Wears Prada,” “Les Misérables”) as a pop singer who becomes entwined in a twisted affair with fashion designer Michaela Cole (“I May Destroy You,” “Black Earth Rising”). Besides its two queer-fan-fave stars, it features trans actress Hunter Schafer (“Euphoria”), FKA Twigs, and Jessica Brown Findlay (“Downton Abbey”) in supporting roles, and to top it all off, it includes a soundtrack full of original songs. With a celebrated director behind it and an award-winning pair of leading ladies, this one has all the potential of a future classic.

The Devil Wears Prada 2 (Theaters, May 1). Meryl Streep is back as Miranda Priestley, need we say more? We know the answer to that is “no,” but we still need to remind you that Anne Hathaway, Emily Blunt, and Stanley Tucci are all part of the deal, too, as this hotly anticipated sequel hits the screen just ahead of the summer rush. Along for the ride are Kenneth Branagh, Justin Theroux, Lucy Liu, B.J. Novak, Conrad Ricamora, Sydney Sweeney, Rachel Bloom, Donatella Versace, and Lady Gaga herself. We trust that will be sufficient to ensure that you will show up on opening day – dressed accordingly, of course.

The Sheep Detectives (Theaters, May 8) Rounding out our roundup with a fun-for-the-family treat that blends live action with animation for an inter-species “whodunnit” with an all-star array of talent, this adaptation of Leonie Swann’s 2005 novel “Three Bags Full” centers on a flock of sheep as they attempt to solve the murder of their beloved shepherd. Boasting onscreen performances from Hugh Jackman, Emma Thompson, Nicholas Braun, Nicholas Galitzine, and Molly Gordon, along with character voices provided by Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Bryan Cranston, Chris O’Dowd, Regina Hall, Patrick Stewart, Bella Ramsey, Brett Goldstein, and Rhys Darby, this one might be just the kind of lightweight entertainment we all need as we move deeper into the confounding year of 2026.

And if not, stay hopeful – the films and shows of summer will be here soon enough.

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoToo afraid to leave home: ICE’s toll on Latino HIV care

-

Movies5 days ago

Movies5 days agoIntense doc offers transcendent treatment of queer fetish pioneer

-

Colombia4 days ago

Colombia4 days agoClaudia López wins primary in Colombian presidential race

-

The White House3 days ago

The White House3 days agoTrump will refuse to sign voting bill without anti-trans provisions