Books

Tori Amos memoir ‘Resistance’ both profound and opaque

Singer/songwriter writes movingly of LGBT issues, family death while keeping the curtain closed on some aspects of her life and passions

‘Resistance: a Songwriter’s Story of Hope, Change and Courage’

By Tori Amos

Atria Books

Released May 5

272 pages

$26

A somewhat common — but far from universal — observation in Tori Amos fan circles is that her newer albums just aren’t as good as her definitive ‘90s masterpieces.

This isn’t unique to Amos. Some artists only have one or two good albums in them total (Alanis Morissette, Jewel) but keep issuing new albums that feel creatively spent. Some, like Lauryn Hill, don’t even bother to try. How many artists can keep a decade-long, white hot streak going indefinitely? And continue blowing the minds of fans who just get more jaded and less easy to impress as they, like the artist, age?

But even Amos herself has seemed curiously uninvested in later albums like “Native Invader” (2017) and “Unrepentant Geraladines” (2014). Her last tour was dubbed the “Native Invader Tour,” yet at her last area appearance in 2017, she played only two songs from the “Native Invader” album (and one was a bonus track at that!). That was typical of her shows that year. This is drastically reduced from her earlier practices. There are always a few standout tracks on each, but the overall impact has felt curiously clinical, musically bloodless. (If you want a super deep dive on this topic, Matthew Barton wrote a brilliant essay this week for The Quietus.)

What has become almost more interesting, though, is what she’s had to say, not sing. She’s always game to do a bounty of press — print and video/TV — with each new cycle (radio, of course, hasn’t played her for ages and never did much anyway) and the Amos we’ve gotten to know in these exchanges (a 2017 Vulture chat is especially good) is wise, illuminating, kooky and engaging.

Thankfully, a lot of that translates into her new memoir “Resistance: a Songwriter’s Story of Hope, Change and Courage,” out this month from Atria Books. It follows her 2005 memoir “Piece by Piece.” Its main thesis — that artists have a social responsibility to combat mercenary forces both political and systemic — is reasonably supported but far from what’s most interesting about it.

Although Amos has always had queer sensibility (she’s straight), what’s pleasantly surprising about the book is how much queer content it contains. In Amos’ mind, sexism — she argues convincingly it’s rampant in the music industry — and homophobia are twin sins and that’s linked her cozily with gay men since her early days playing at Mr. Henry’s a gay bar in Georgetown where Amos got her start at age 13, an experience the daughter of a United Methodist pastor describes in religious terms.

“Perhaps because it was gay men who took me under their wing when I was 13 and taught me how to survive — even at times through a large dose of reality, spelling out how a teenage girl in Washington could be manipulated — well, that’s its own song and those rivers run deep. Those fairy godfathers trying to teach me a drop of grace can go a long way, a lesson that my inner lioness needs reminding of a lot, but they gave and gave and gave and did not give up on me. Praise Jesus. So they led me, baptized in the barroom, to strength, to visibly blossom.”

She also writes of a 2014 concert she gave in Moscow on a stage at Crocus Arena where Putin was to appear the following day. Outraged by a 2013 “gay propaganda” law Putin had signed that made it illegal to tell LGBT Russian youth they were normal and give them reliable information on sexual orientation and gender identity, Amos tailored her set list to reflect her inner protest.

“The persecution of the LGBTQ community was — and is — real and terrifying,” she writes. “My set list in Moscow would speak loud and clear.”

Amos also writes briefly of a similar experience at at 2014 concert she gave in Istanbul.

Throughout the book, Amos-penned songs are shared that dovetail the various topics she covers. “Ophelia” closes a section about the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in 2018 and “Cornflake Girl” is placed with a painful essay on female genital mutilation (it’s way more common in parts of the world than you’d guess).

Things lag a bit in a lengthy passage about the 1979-1981 Iran hostage crisis in which 52 Americans were held hostage for 444 days during a diplomatic standoff. Amos, still a D.C. piano bar regular at the time, writes of the change in the air when Reagan took office. Then Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill even joined her once at the piano to sing “Bye Bye Blackbird,” which she writes of fondly. Although always interesting to hear about, it at times feels like Amos is trying to play up her inside-the-Beltway locale to be of more import than it likely was. She writes of observing Hill movers and shakers conducting business over cocktails but how much could she really have overheard belting away at the ivories?

For me, the most gripping passages were the ones from Amos’ own life such as the initial rejection of her debut solo album “Little Earthquakes” by Atlantic Records in 1991, her experience being in New York City on 9-11 and her mom’s 2019 death following a debilitating stroke.

Other standout passages include fresh perspectives on Amos’ fraught relationship with Baltimore’s Peabody Conservatory (she was kicked out as a teen but invited back in 2019 to give a commencement address) and descriptions of her artistic process where she’s at times ethereal (she speaks often of the muses that bring her inspiration) and practical describing the often painstaking process of culling her musical noodlings and fragments into usable sonic wheat.

Her observations are at times profound. She writes of what she believes is the fallowness of the notion of artistic barrenness: “People who are addicted to power … can weaponize the thought of being creatively barren in order to debilitate the artist. They target artists specifically because they know that artists have the ability to reach the public in ways no one else can.” Ever worked with a narcissist? Those words ring true.

There are handfuls of “Gold Dust” (to use one of Amos’s songs) scattered piquantly throughout “Resistance.”

Despite the sometimes heavy topics, the essays are fairly short and tight. It feels like a nice, long visit with a trusted ally but she’s sharing not just off the top of her head, but on topics she’s in many cases spent a lifetime pondering — grief, honoring one’s instrument and inspiration, the price of selling out, how to stay in the game when the straight, white old boys’ club hold all the good cards and so on.

My quibbles are that I was hoping her husband and musical partner Mark Hawley — an artistic enigma who seems to not just enjoy but practically demand staying in the background — had emerged as a more fully formed figure. So little is known about him, yet so heavy has his influence been on Amos’s career, that he looms like a specter over the Amos universe.

It’s also highly odd that Amos mentions the death of her sole brother only in passing (were they simply not close? If so, why?) and that former boyfriend Eric Rosse is mentioned just once. He was the co-producer of her career-defining first two solo albums; their breakup, which Amos has never said much about, in part inspired her masterwork “Boys for Pele” (1996). They’ve been apart long enough now, surely she can assess his contributions to her formative works more unemotionally now, one presumes. So why does she barely acknowledge him?

And while Amos does write movingly of how mortifying the Y Kant Tori Read (her first band, which bombed with one 1988 album) era was, she’s frustratingly scant on details — did she feel musical kinship with her bandmates? How did they form? When did they officially disband? Did they provide any solace in the failure or accept any of the responsibility? Where are they now? And perhaps, more metaphysically, could there have ever been a “Little Earthquakes” if Y Kant Tori Read hadn’t happened? Amos blames herself for sinning against her art and her instrument and selling out but without sin there’s no redemption, artistic or otherwise.

That, perhaps, is what’s missing from Amos’ later work. Even with the usual struggles life eventually brings us all — the death of a parent most pronouncedly — Amos is almost too wise, too mature, too stable, too grounded to conjure up the woozy heat of earlier songs like “Bliss,” “Spark” or “Blood Roses.” It’s unfair, one must acknowledge, to expect her to maintain the kind of white-hot streak she had going ’til about “To Venus and Back” (1999). What would a 2020 Kurt Cobain album sound like had he lived?

Still it’s a bittersweet aftertaste “Resistance” leaves — as warmly as it goes down — that these are considerations a long-time fan can’t help but ponder.

Books

New book offers observations on race, beauty, love

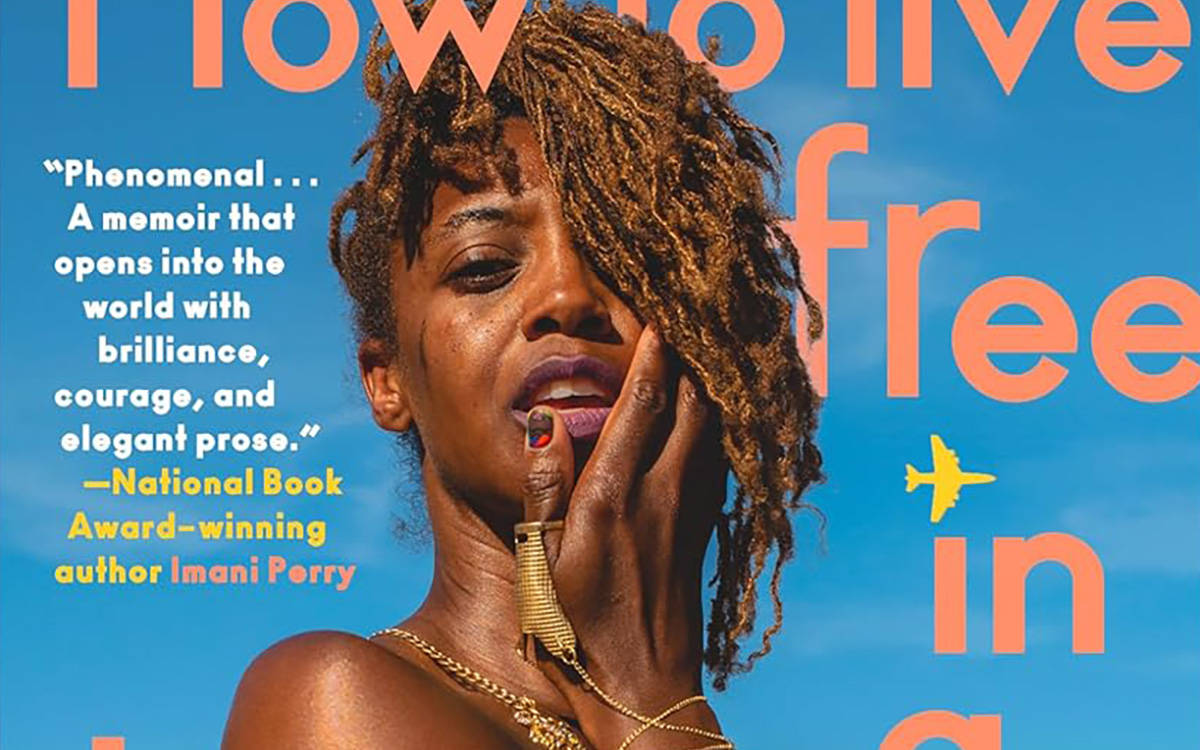

‘How to Live Free in a Dangerous World’ is a journey of discovery

‘How to Live Free in a Dangerous World: A Decolonial Memoir’

By Shayla Lawson

c.2024, Tiny Reparations Books

$29/320 pages

Do you really need three pairs of shoes?

The answer is probably yes: you can’t dance in hikers, you can’t shop in stilettos, you can’t hike in clogs. So what else do you overpack on this long-awaited trip? Extra shorts, extra tees, you can’t have enough things to wear. And in the new book “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” by Shayla Lawson, you’ll need to bring your curiosity.

Minneapolis has always been one of their favorite cities, perhaps because Shayla Lawson was at one of Prince’s first concerts. They weren’t born yet; they were there in their mother’s womb and it was the first of many concerts.

In all their travels, Lawson has noticed that “being a Black American” has its benefits. People in other countries seem to hold Black Americans in higher esteem than do people in America. Still, there’s racism – for instance, their husband’s family celebrates Christmas in blackface.

Yes, Lawson was married to a Dutch man they met in Harlem. “Not Haarlem,” Lawson is quick to point out, and after the wedding, they became a housewife, learned the language of their husband, and fell in love with his grandmother. Alas, he cheated on them and the marriage didn’t last. He gave them a dog, which loved them more than the man ever did.

They’ve been to Spain, and saw a tagline in which a dark-skinned Earth Mother was created. Said Lawson, “I find it ironic, to be ordained a deity when it’s been a … journey to be treated like a person.”

They’ve fallen in love with “middle-American drag: it’s the glitteriest because our mothers are the prettiest.” They changed their pronouns after a struggle “to define my identity,” pointing out that in many languages, pronouns are “genderless.” They looked upon Frida Kahlo in Mexico, and thought about their own disability. And they wish you a good trip, wherever you’re going.

“No matter where you are,” says Lawson, “may you always be certain who you are. And when you are, get everything you deserve.”

Crack open the front cover of “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” and you might wonder what the heck you just got yourself into. The first chapter is artsy, painted with watercolors, and difficult to peg. Stick around, though. It gets better.

Past that opening, author Shayna Lawson takes readers on a not-so-little trip, both world-wide and with observant eyes – although it seems, at times, that the former is secondary to that which Lawson sees. Readers won’t mind that so much; the observations on race, beauty, love, the attitudes of others toward America, and finding one’s best life are really what takes the wheel in this memoir anyhow. Reading this book, therefore, is not so much a vacation as it is a journey of discovery and joy.

Just be willing to keep reading, that’s all you need to know to get the most out of this book. Stick around and “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” is what to pack.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Story of paralysis and survival features queer characters

‘Unswerving: A Novel’ opens your eyes and makes you think

‘Unswerving: A Novel’

By Barbara Ridley

c.2024, University of Wisconsin Press

$19.95 / 227 pages

It happened in a heartbeat.

A split-second, a half a breath, that’s all it took. It was so quick, so sharp-edged that you can almost draw a line between before and after, between then and now. Will anything ever be the same again? Perhaps, but maybe not. As in the new book “Unswerving” by Barbara Ridley, things change, and so might you.

She could remember lines, hypnotizing yellow ones spaced on a road, and her partner, Les, asleep in the seat beside her. It was all so hazy. Everything Tave Greenwich could recall before she woke up in a hospital bed felt like a dream.

It was as though she’d lost a month of her life.

“Life,” if you even wanted to call it that, which she didn’t. Tave’s hands resembled claws bent at the wrist. Before the accident, she was a talented softball catcher but now she could barely get her arms to raise above her shoulders. She could hear her stomach gurgle, but she couldn’t feel it. Paralyzed from the chest down, Tave had to have help with even the most basic care.

She was told that she could learn some skills again, if she worked hard. She was told that she’d leave rehab some day soon. What nobody told her was how Les, Leslie, her partner, girlfriend, love, was doing after the accident.

Physical therapist Beth Farringdon was reminded time and again not to get over-involved with her patients, but she saw something in Tave that she couldn’t ignore. Beth was on the board of directors of a group that sponsored sporting events for disabled athletes; she knew people who could serve as role models for Tave, and she knew that all this could ease Tave’s adjustment into her new life. It was probably not entirely in her job description, but Beth couldn’t stop thinking of ways to help Tave who, at 23, was practically a baby.

She could, for instance, take Tave on outings or help find Les – even though it made Beth’s own girlfriend, Katy, jealous.

So, here’s a little something to know before you start reading “Unswerving”: author Barbara Ridley is a former nurse-practitioner who used to care for patients with spinal cord injuries. That should give readers a comfortable sense of satisfaction, knowing that her experiences give this novel an authenticity that feels right and rings true, no faking.

But that’s not the only appeal of this book: while there are a few minor things that might have readers shaking their heads (HIPAA, anyone?), Ridley’s characters are mostly lifelike and mostly likable. Even the nasties are well done and the mysterious character that’s there-not-there boosts the appeal. Put everyone together, twist a little bit to the left, give them some plotlines that can’t ruined by early guessing, and you’ve got a quick-read novel that you can enjoy and feel good about sharing.

And share you will because this is a book that may also open a few eyes and make readers think. Start “Unswerving” and you’ll (heart) it.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Examining importance of queer places in history of arts and culture

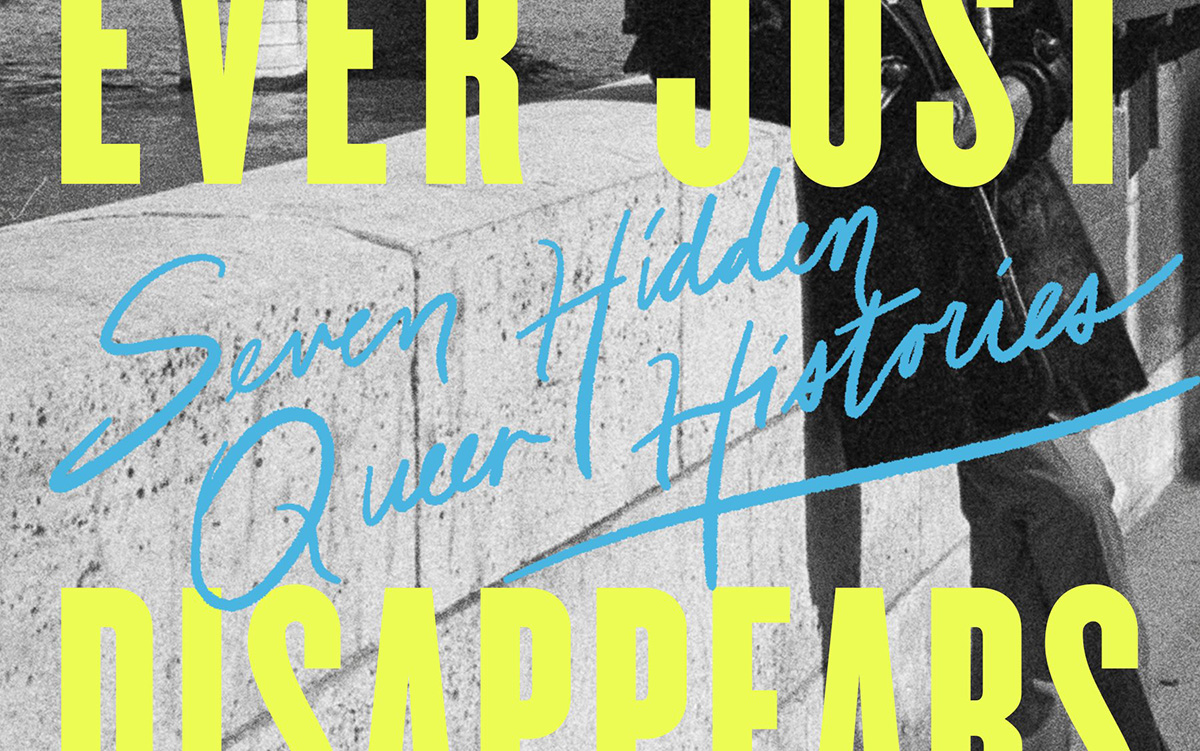

‘Nothing Ever Just Disappears’ shines with grace and lyrical prose

‘Nothing Ever Just Disappears: Seven Hidden Queer Histories’

By Diarmuid Hester

c.2024, Pegasus Books

$29.95/358 pages

Go to your spot.

Where that is comes to mind immediately: a palatial home with soaring windows, or a humble cabin in a glen, a ramshackle treehouse, a window seat, a coffeehouse table, or just a bed with a special blanket. It’s the place where your mind unspools and creativity surges, where you relax, process, and think. It’s the spot where, as in the new book “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” by Diarmuid Hester, you belong.

Clinging “to a spit of land on the south-east coast of England” is Prospect Cottage, where artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman lived until he died of AIDS in 1994. It’s a simple four-room place, but it was important to him. Not long ago, Hester visited Prospect Cottage to “examine the importance of queer places in the history of arts and culture.”

So many “queer spaces” are disappearing. Still, we can talk about those that aren’t.

In his classic book, “Maurice,” writer E.M. Forster imagined the lives of two men who loved one another but could never be together, and their romantic meeting near a second-floor window. The novel, when finished, “proved too radical even for Forster himself.” He didn’t “allow” its publication until after he was dead.

“Patriarchal power,” says Hester, largely controlled who was able to occupy certain spots in London at the turn of the last century. Still, “queer suffragettes” there managed to leave their mark: women like Vera Holme, chauffeur to suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst; writer Virginia Woolf; newspaperwoman Edith Craig, and others who “made enormous contributions to the cause.”

Josephine Baker grew up in poverty, learning to dance to keep warm, but she had Paris, the city that “made her into a star.” Artist and “transgender icon” Claude Cahun loved Jersey, the place where she worked to “show just how much gender is masquerade.” Writer James Baldwin felt most at home in a small town in France. B-filmmaker Jack Smith embraced New York – and vice versa. And on a personal journey, Hester mourns his friend, artist Kevin Killian, who lived and died in his beloved San Francisco.

Juxtaposing place and person, “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” features an interesting way of presenting the idea that both are intertwined deeper than it may seem at first glance. The point is made with grace and lyrical prose, in a storyteller’s manner that offers back story and history as author Diarmuid Hester bemoans the loss of “queer spaces.” This is really a lovely, meaningful book – though readers may argue the points made as they pass through the places included here. Landscapes change with history all the time; don’t modern “queer spaces” count?

That’s a fair question to ask, one that could bring these “hidden” histories full-circle: We often preserve important monuments from history. In memorializing the actions of the queer artists who’ve worked for the future, the places that inspired them are worth enshrining, too.

Reading this book may be the most relaxing, soothing thing you’ll do this month. Try “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” because it really hits the spot.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

State Department4 days ago

State Department4 days agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

District of Columbia3 days ago

District of Columbia3 days agoCatching up with the asexuals and aromantics of D.C.

-

South America2 days ago

South America2 days agoArgentina government dismisses transgender public sector employees

-

Maine3 days ago

Maine3 days agoMaine governor signs transgender, abortion sanctuary bill into law