National

Locked up in the Land of Liberty: Part III

Yariel Valdés González was granted asylum on Sept. 18, 2019

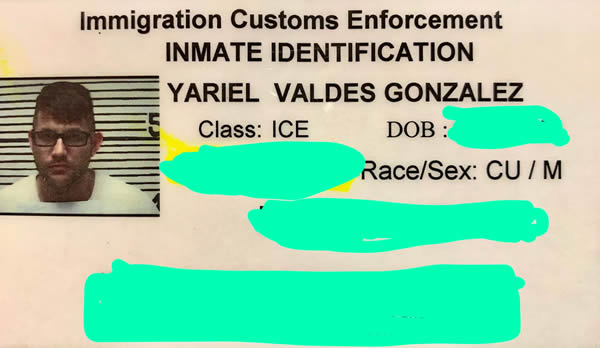

Editor’s note: Washington Blade contributor Yariel Valdés González fled his native Cuba to escape persecution because of his work as an independent journalist. He asked for asylum in the U.S. on March 27, 2019. He spent nearly a year in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody until his release on March 4, 2020.

Valdés has written about his experiences in ICE custody that the Blade is publishing in four parts. The Blade has already published parts I and II.

Doomsday (Sept. 18, 2019)

My third and final hearing finally took place on Sept. 18. It was more than three hours of questions from my lawyer and the prosecutor, of allegations and tension. A lot of tension. My fate would be decided as the sacred scriptures predict will occur one day for humanity.

Lara and I the night before spent our time reviewing my testimony, the difficult questions we could expect, and it tested my ability to react to unexpected situations. I came out of the meeting much calmer, although I would have preferred extra hours to feel totally confident when I was in front of His Honor.

My mind and senses were more focused when the time came. I was much stronger to face this defining moment in my life. Several changes in the context also contributed to this: They changed the judge a few weeks earlier. He is no longer the esteemed Grady A. Crooks, but Timothy Cole, a Miami magistrate who had already granted asylum to a few Cubans in Bossier. The possibility that my lawyer would be next to me during the hearing, the 12-day extension and the date of my final hearing were other changes that contributed to me feeling more secure on the stand.

After she took an oath before the laws of this country by standing with her right hand raised, my legal representative had one hour to present my case and offer my oral testimony. It was then when I remembered one of her recommendations, which was to always respond like a boxer’s sharp blow: Direct, concise and sure, since I was prone to ramble and sometimes veer off subject.

“The questions should be answered only with what is necessary to avoid possibilities for errors, wasting time or other questions,” recommended Lara. “Every word can and will be used against you here, that is why you have to be extremely careful when speaking.”

Lara’s part passed without many interruptions. I felt calm and sure of myself. The judge typed on his computer, reviewed papers and arranged files while I testified. He didn’t ask me any questions, so I hadn’t planted any doubts for him. It was a magnificent sign.

The only problems at that point had been with the interpreter, a middle-aged man who was probably of Cuban origin, who came up blank with words as simple as “subversion” and was nervous, like he was a rookie on his first day of work. Maybe it was. The thing with translators is that you have to cut off the oratory, mutilate the ideas to give them time to do their work. It’s like talking to someone who interrupts you all the time.

The government prosecutor had 45 minutes for cross-examination, the most feared part of the trial. I would have a high likelihood of winning if I successfully overcame his questions.

The man’s voice reached me in an accusatory tone, as if I were being tried for some heinous crime. His voice was a merciless whip on my back, seeking to whip me like a vile sinner. One by one he took the evidence from me in his attempt to discredit me, to present me to His Honor as a liar and vehemently pointed out some inconsistencies, which I clarified in due course.

As I answered his questions, at times tinged with irony, anguish enveloped my head in a balloon of pessimism and nerves. I must admit the prosecutor did his job very well. He searched and scoured the internet and looked closely at every piece of evidence I had given him.

Lara took notes on her computer during his cross-examination and made several objections when she perceived any malicious practice or intention from the Department of Homeland Security representative.

My lawyer had a second chance with me, this time to clarify some questions my indomitable opponent raised and to re-ask some questions that, at the prosecutor’s insistence, I could not answer properly. Those were fortunately my last words at the hearing and the interpreter then left the room.

His Honor ordered both parties to make their closing arguments. Lara, in my defense, stated that there was no doubt about my work as an independent journalist in Cuba or that I had been threatened and persecuted by State Security agents as part of a pattern of intimidation, orchestrated by the Cuban dictatorship to stop the work of the free press on the island.

There was enough evidence of the conditions of the country for “unofficial” reporters, considered as machines “subverted” of socialist principles and disseminators of “false news without foundation.” The evidence of the attacks against me confirmed that I had been and was still a target to be watched by the regime and that my freedom, as well as that of my family, was in danger.

The government representative, instead and specifically, signaled that I was not worthy of the protection of the United States because my asylum petition was frivolous, because I had “fabricated” evidence and my testimony had been vague and full of inconsistencies. I could hardly believe the prosecutor’s accusations against me. My poor English allowed me to understand only a limited amount of his closing argument.

I felt totally defeated. Terror moistened my stare and Lara’s hand squeezed mine, trying to calm my fears with her support. The judge briefly addressed me, but nerves had clouded my understanding and I was unable to understand anything. Lara noticed that I was totally confused and wrote to me on a piece of paper: “We won.” I looked at her in disbelief and she confirmed the victory with a nod.

The hearing was not yet over. The judge had not read his oral decision, a broad opinion that included the reasons why he granted me asylum. The respectable Judge Cole found my statement credible as well as each of the responses to the prosecutor’s accusations. His final ruling managed to revive my spirit, which had been withered minutes before.

The intense hug from my lawyer was the end of more than three hours of battle. Being the center of a hearing like this is like being in the middle of a severe storm: Some winds push you to one side, others carry you in the opposite direction, but I resisted them strongly. I could, at the end, see the sun that illuminated everything after so much storm.

A hope that fades away

My joy grew when I entered the pod. A handful of friends eagerly awaited the outcome and rushed towards me with hugs and heartfelt congratulations. They formed a circle around me to hear every detail. I was still in a state of disbelief, unable to accurately answer every question from my comrades. It was impossible for me to narrate three hours of judgment, so I said the most important thing for me to do was to go to the phone.

The first number I dialed was Michael’s. When I said, “We won!” because this victory is his too, he burst into tears like a baby.

“Oh my God! Oh my God!” he repeated, overcome by the news on the other end of the line.

My aunt and uncles in Miami filled my ears with a chorus of vibrant exclamations, and my mother could not contain her emotion. I heard her voice loud and clear.

I explained to everyone that they only had to wait a few days to find out if the government would appeal the judge’s decision, otherwise I would finally be released in about a week. Two Cubans, who also won their final hearing and anxiously counted the hours to get out of this hell, were in the same situation.

My despair grew over the next few days. I had almost no appetite; my sleep was intermittent; my brain punished me by insistently remembering the hearing and the prosecutor’s harsh voice intruded on my positive thoughts.

The document with the official result arrived the next day and little by little I saw how my countrymen who had obtained asylum were released, even one whose hearing was the same day as mine without a lawyer and without evidence.

The ghost of the appeal began to haunt my senses and every time an officer opened the door of the shelter a sharp pain shot up the left side of my chest. The automated tip line said that ICE’s deadline to appeal to a higher court for a second opinion was Oct. 18, a month after I won asylum.

A visit from my attorney confirmed my fears. She told me that the government had requested a review of my case to the Board of Immigration Appeals in Virginia, a panel with several immigration judges who will determine if there was any error by the magistrate who handled my asylum case. My hopes of getting out were reduced to zero in one fell swoop and I was once again cornered like prey before a skilled hunter.

Anguish ran through my cheeks and Lara squeezed my hands and told me that I must be strong. They are very easy words to say; but they mean extra strength, poise and a resistance that I was not sure I had. Lara couldn’t answer any of my questions. She was facing such a situation for the first time. I had to investigate how the process would go and what real chances we had to win again.

Then, in a brief retrospective of my life, I remembered that each momentous step has cost me a sea of suffering. One of my uncles tells me that I must be the son of Chango, a Santería saint, because every change has always been preceded by high doses of sacrifice and dedication.

Many might say that successes are only won after many bitter drinks. I am much stronger, especially with this one, because my freedom is at stake, not only from this place, but from the Cuban dictatorship.

Pipo and I are now the only ones who are left. Pipo is what we affectionately call a Pakistani man who also won asylum and the government has appealed his case. We talk a lot about our respective situations, because we share the same fears and anxieties. The way forward is absolutely uncertain.

Happiness is gone (Oct. 18, 2019)

Today is exactly one month since I won asylum and I am still here. A month ago, it was all hope and joy, but those days are long gone. Happiness does not last long in the poor man’s house, as my mother would say. Today, by the way, is also a month since I haven’t spoken to her, not to my father, not to my brother, not to Lester, not to my friends in Cuba.

I’m afraid of breaking down on the phone and I always try to be strong on the calls, especially for my mom. It is the least I can do. I feel like she covers herself with a blanket of strength and positivity when she responds to me. Her words inject me with comfort and reassurance to move on.

I know that she is suffering a lot with all this. If she notices me discouraged and depressed, she will be more so and I don’t want to add more worries than she already has. These days I only talk to my aunt and uncle in Miami and Michael. With them communication has become a daily habit, perhaps that is why it is less painful for me. There are days when we do not have much to talk about and the calls are filled with slightly trivial topics and about the day-to-day of our lives.

At least once a day I think about that Sept. 18. I remember the hearing that lasted more than three hours. They now seem a bit far away, but I recreate that morning full of nerves and adrenaline in my mind. The questions and “inconsistencies” the prosecutor indicated and for which he is surely appealing Timothy Cole’s decision return.

Those questions haunt me every day, at all times. Just when I think about it, there they are. I checked in the system yesterday. There is a line for immigrants call to know the status of their processes, and the appeal against me “was received” and “is pending” a decision.

The government’s appeals undoubtedly go much easier, luckily. The claims made by migrants last at least five months. They are months of waiting and uncertainty where immigrants manage to “relax” a bit. I say “relax” because the hardest part is over. The only thing left to do now is to send a form with the request for appeal and a plea of self-defense, but without appearing any more in court.

Now the decision rests with a group of judges in Virginia who make up the Board of Immigration of Appeals, who review the judge’s decision, each piece of evidence presented, the transcripts of all the hearings and how much material relates to the asylum request. Only a few of the appeals reverse the negative result.

Most of the people here try to cheer me up, telling me that it is unlikely that the higher court will order that the decision of my case be changed. It is only a sterile process, but to which the government is entitled, as we know. However, I am not so calm. I’m not so convinced. My mind cannot be entirely positive, perhaps because when it has been, it has thrown me to the ground. That’s why I hold back and run away from false hopes.

Today is also the 50th anniversary party of the Washington Blade, America’s oldest LGBTQ publication and of which I have been a contributor for a few months. Michael told me that they were thinking of me and that this anniversary was mine too. I hope I can attend the next one and get to know America’s capital and the colleagues who have supported me so much in this process. It would be a real privilege.

Today I have a little desire to exercise. I haven’t worked out for days. Depression completely shuts me down, even the desire to bathe has gone away. I see my friend Erick exercising and that’s where I plan to go. My head hurts a little. I just hope the routine eases it. Then I’ll try to call for news. I still don’t know if I will have the strength to listen to my mother’s tender voice. I do not know yet.

I hate weekends! (Oct. 20, 2019)

Saturdays and Sundays in jail are more monotonous and boring than the rest of the week, at least for me. Others prefer these two days because there is more tranquility. Officers do not arrive all the time calling for the doctor, court or the commissary and the long morning sleep is not interrupted, although they continue to wake us at 4 a.m. for breakfast.

The truth is that I am not a fan of sleep. It is difficult for me to stay in the bunk after nine, but people here sleep until lunch, which arrives at around 11. There is not much else to do. I wish I could be so lazy and sleep without the slightest noise waking me up.

I laid down again today after breakfast and managed to doze a bit and woke up totally disoriented. I had no idea what time it was. I didn’t know if I had had lunch or dinner. It was a horrible feeling and it is not the first time it has happened to me.

I also dreamed. I don’t usually do it often and I usually forget about it. Waking up today was definitely not pleasant, well it never is. Opening your eyes and seeing yourself still locked up is not particularly pleasant.

Sundays are the days for changing the sheets and today they also took the blanket to wash. The bedspread goes to the laundry once a month. It is unlikely that someone will be able to fall asleep again after being left without a sheet and without a comforter. The pod wakes up, because Sunday is also a search day.

Officers check every occupied bed and every empty bed. Today they were particularly interested in beds where no one sleeps. They know that people usually hide forbidden objects in those drawers without being able to blame them on anyone. The main objective of the searches is to collect everything that they consider “contraband,” such as leftovers of the food they provide us, medicine, bracelets, photos, clotheslines and whatever they find outside of “their law,” which is usually quite narrow.

They check under the mattresses and in each other’s drawers. As we were already waiting for this day, only a few comrades saved the food they brought us for breakfast. The only food that is allowed to remain with our belongings is that which we buy at the commissary.

The officers are merciless and wipe out any trace of cooked food. According to them, we can get sick with leftover food, which also attracts all kinds of vermin that feed on food debris.

All of this is very true, but in these conditions, where hunger abounds, the wisest thing to do is to have something to put in your mouth when the last meal has already left your stomach. I myself hid two pieces of bread and butter between my sweater and my pants. The searches, fortunately, do not include our bodies. Almost all of us hide some food, like squirrels that bury acorns in fall to have food in winter. Some don’t go to great lengths to hide their supplies under their uniforms, but I try to be discreet. They found almost nothing today because they were not very thorough in the search and confiscation of food.

They removed, however, a wrapper with pills from a Cuban and I had to go there as a translator. It is also forbidden to store medications, with the exception of those that you buy in the commissary, but those are easy to recognize because they come in their case. They were instead loose. They looked like a small drug order, highly suspicious to officers.

The countryman, scared as he was, began to hesitate, giving a different version of each question, a victim of his own nervous and improvised speech. He justified his small pharmacy by saying that they allergy medications, and that the infirmary had prescribed them for him. The officer’s facial expressions were extremely intimidating.

And it is for good reason. The punishment for storing medicines results in a visit to the hole for as many days as the officer deems appropriate, but today Pantera — that’s what we call a sheriff with a dark complexion and the sharp eyes of a wild animal — was happy and did not impose any punishment on him. He only decided to collect the pills and remind him that the storage and smuggling of medicines was prohibited. He would naturally verify his justification with the doctors.

A friend in C-2 spent four days in isolation for storing pills. Today, however, they decided to turn a blind eye. All of us, at some point or other, have saved and received pills from someone.

Those who have a daily prescription for a medication sometimes do not want to take it and give it away or simply exchange it for something more attractive to them. This is how we manage to fill the coffers with different medicines for various ailments without going to the doctor to beg for them, much less buying them at the commissary at scandalous prices.

My services as an interpreter were demanded again on this Sunday, this time in the pod out front. There was a Cuban in the hallway who had resisted giving his food to the officer. That was the Pantera version. The Cuban claimed that he was going to open the trash can himself and throw the food away, but the officer prevented him. They interpreted the gesture of pushing away the food tray as a “threat,” resisting his authority.

There can be no struggles because the immigrant will end up immobilized on the floor with his hands behind his back and a good scare that is not at all necessary. That’s how the Cuban ended up: Facing the ground and with the entire weight of the deputy on his back to immobilize him. He was now arguing with Pantera over the atrocity of that completely unjustified act. There really was no need for that. Nobody here is stupid enough to attack an officer, but they apply self-defense with the slightest doubt.

The comrade was a repeat offender. I had gone to the hole on another occasion to explain to him, also through Pantera, that he could not try to keep the food when the officer was going to throw it away. He definitely hadn’t learned his lesson and all three of us were there again, repeating the same absurd rules.

There were, fortunately, no more severe consequences and the Cuban returned to the pod. He was saved from punishment. He thus confirmed that Pantera had a good day today. A few countrymen inside the dorm yelled at an officer about how unfair the treatment of their comrade was, but it was like swimming in the sand. The Cubans shouted in Spanish, a little upset over the attack on their friend, but the officer did not take it for granted and soon closed the door in their faces.

I joked with a friendly young officer when I was returning to my dorm. I told him that he was going to start charging my services as an interpreter at $10 an hour. He laughed and told me that he could only pay me five and I accepted.

Weekends are also the time for the barber shop. The officers return the clippers, owned by some immigrants, to cut our hair and shave us. There is no barber shop in Bossier. We do it in a corner, next to the microwave, the only place in the pod where there is an electrical outlet and where hair can fly into food. The microwave is inevitably full of hairs, which fly off when cut by improvised barbers.

Yesterday, Saturday, they had already run the machine over my face to shave. I don’t have to worry about taking turns because I don’t need to cut my hair yet. The lines are usually quite long and the barber’s friends take priority. Some barbers do not charge, but others require a soup for the shave. It is their way of subsisting.

I also called my mom yesterday. We hadn’t talked in a month and it was less emotional than I thought. We talked calmly, only she and I. My brother had just left. I also called my father, who was at the home of the wife of one of his closest friends. I spoke with them and especially with her, a great Mexican woman, who had opened the doors of her home and her heart to me since I met her.

She allowed me to stay at her house for approximately a month while I was waiting to legally enter the United States. Those were days when our friendship grew closer and her kindness managed to win me over. Maybe that’s why this call was more difficult and I ended up saying goodbye to my father with a cracked voice and wet eyes.

I was determined today to spend the rest of my telephone money and so I contacted Lester. It was also a month since I last heard his voice. I noticed it was affectionate, considering the situation in which we were.

I still can’t figure out if we’re still dating. My heart has adjusted a bit to this loneliness and I no longer cry my heart out when I talk to him. I tried to take advantage of the remaining $4 on the card and update him on everything that had happened, even though he already knew from my aunt.

“I love you,” he told me at the end and I had the feeling that everything was as before.

Curtain up! The show begins (Oct. 23, 2019)

It was not yet dawn when an officer called my name. I received an envelope from Virginia after the very early morning medication delivery. The Court of Immigration Appeals notified me that they had received an appeal from the Department of Homeland Security against me on Oct. 3. They officially informed me that a higher court would review my asylum case. Although it was something that I already knew, I couldn’t help but feel a bit uneasy. I couldn’t fall asleep again, so I started my day.

Bossier has been inspected for a few days. Mysterious men in suits and ties as well as elegantly dressed women were prowling the corridors. They entered the control tower today and from there they had a panoramic view of the four dorms.

Crawford, the second commanding officer, a few minutes earlier had come to give us some coloring paper and crayons. It was the play’s first act. The audience was about to arrive and the actors had to be properly dressed, in their positions and ready to smile.

The staging was brief. The visitors decided not to get too involved and did not step out of the fish bowl that duly prepared for them in advance. Some speculated that they were from ICE, others thought DHS (Department of Homeland Security.) The truth is that we never had the security of anything, as always.

During the course of the day, several entered the dorm to inspect it: One checked the telephones, another checked the bathrooms and the microwave. A woman joined us for lunch and the last one arrived to learn the immigrants’ opinion about the prison’s conditions.

It was an inspection just for that. We still seized the opportunity. I was one of those who were chosen to answer the visitor’s questions, because I defend myself a bit in English.

He was a middle-aged man with white hair and a noble expression. He asked about razors. I told him that we shaved every weekend with a hair clipper.

“Is the same hair clipper for shaving,” asked the man.

“Yes,” I replied.

His face made a grimace of disgust and I immediately showed him the cut on my upper lip. I had been cut, unintentionally of course, with the clipper a few days ago. The rest of my companions immediately approached. One said to put on television channels in Spanish. We complained about the cold showers and the poor quality of the food.

The man pointed, as did the officer who accompanied him. I asked for a clock in the dorm and another microwave. The lines to heat food are endless when 70 people depend on just one. The rest of the dorms have two, but they keep us with one. We haven’t received a replacement since the second one broke.

The visit did not last long, 15 minutes perhaps. The officer turned away, and so did the visitor. I was once again left with the impression that nothing would improve. Maybe yes, you have to give them the benefit of the doubt.

Dinner, around 4 p.m., arrived as an omen that everything will remain the same. The menu didn’t even change on the day of the visit. At least they were sincere for that part. They weren’t fooling them with a new or improved menu. We received one of the most hated meals: A few slices of bread with a brown sauce with vegetables and a few pieces of shredded chicken. We call it “bread with vomit,” so you can imagine what it looks like and even worse how it tastes.

Lower and raise the curtain: Act II (Oct. 24, 2019)

Most of the dorm was still sleeping peacefully. I was in front of the television, hunting for some of the morning news shows. I sometimes watch “Good Morning America,” “Today” or anything else that gives me some news. And there I was, remote control in hand, when the door opened. The jail warden entered with two ICE officers and two other people who, according to what we were told, were part of the inspection to which Bossier was subjected a few days ago.

Curtain up! Act II had begun. I immediately got up from the table and went to put on my yellow uniform shirt. I wanted to get away from the officers and camouflage myself among the rest of the detainees. I did not want to be an active part of this theater, and I certainly did not want to be lied to to my face, to be once again thought of as stupid. I have not, for a long time, wanted to see the faces of those people, who solve nothing every time they come, but the strategy was the other way around.

They immediately asked for someone to help them translate into Spanish and vice versa, even though one of the officers speaks Spanish perfectly. They say he is Cuban, but I don’t know. He was there in front of everyone as part of the show, but I must clarify that I did not like it.

The barrage of questions began, especially about parole. The answers came with the usual old phrase: Each case is different and we are going to look into all your concerns. It is the perfect excuse to use without saying anything.

It was the same old speech, identical phrases and the same disappointed faces who are tired of so much false information. We asked them on several occasions about one thing and they answered with something else. It is the same scenario that I have seen since I have been here.

ICE officials never have a concrete and convincing answer to our concerns, or they just don’t give us the information if they do. They give the impression that they come to improvise before a desperate crowd that is crying out for change and action.

I managed to highlight my particular case to an officer and, of course, he could not clarify any of my doubts. I didn’t know how long the appeals process will take, let alone if I am eligible for parole. I didn’t know if I am in a better or worse position to receive parole, considering that I won asylum and I am not a flight risk, the main excuse they use to deny it. I already went to all my scheduled hearings, but nothing. Not a single answer.

We are probably left with more doubts after these visits. Disappointment and anger could be read on each one of our faces. These encounters are always very frustrating for most. Not so much for me. I’m used to the fact that nothing positive ever comes out of these exchanges. I don’t expect anything from them anymore.

Some took one of the inspectors to a corner to talk privately.

“Whenever you make a request to ICE, keep a copy to have evidence of the claims if they are not handled,” he advised us, as almost always happens.

Deportation matters are the only thing for which these officers are effective. They are agile and attentive there.

Some immigrants speculated that the inspection was also from ICE, only they never said it. We complained about all the issues that are wrong in this prison with the “inspector” with whom we managed to speak: We do not have a set recreation schedule; we cannot shave properly; the food is inedible and everything concerning personal hygiene, including the fact they sell it to us at very high prices at the commissary, among other things.

Our intermediary, a very tall and highly educated young American man, told us they would try to fix everything that was wrong, that they would find a way to pressure the prison to correct some issues that can make life a little more comfortable here. He looked at us with pity, but nothing more. Solutions to our problems were still on hold.

We received terrifying news a few days ago. A Cuban had committed suicide in Richwood, a detention center in Louisiana. He was in isolation and attempted to take his life because he found himself at a dead end. He had applied for parole three times and he had been denied twice. They were considering his case for a third time at the time of his death, but it was too late.

Many think suicide is a “cowardly solution,” an option to erase all problems and suffering in a drastic, final and selfish act. I, on the other hand, think that it takes a lot of courage to go through with a suicide.

Escaping from everything that hurts us in this way is also an understandable act, given the circumstances in which I find myself. There is, of course, a bit of disorder in a mind that carries out a hanging or any other suicide attempt.

There are a few people I know won’t dare to do so, yet many think so. I myself have reached such a point of despair that I have found myself thinking about these atrocities more than once. The very fact that my brain considers them as an option terrifies me and is indicative of how much this is affecting me. I am seriously considering the possibility of going to the psychologist. Maybe they can prescribe some pills to help me get through the tough times through which I’m continually going.

Half a year in La. (Nov. 3, 2019)

One has the feeling that the days inside here do not pass, that time is frozen because my life is frozen. I’ve been living on hiatus for seven months, stuck at a crossroads. Cuba is on one side and the United States is on the other, two antagonistic shores confronting each other, separated, but united at the same time.

It is not yet very clear which of them will be my final destination. Every day the moment to live in freedom in this country becomes more diffuse. Today marks exactly six months since I have been in Louisiana. May 5 seems so distant now, but 180 days have since passed and I still don’t see the end.

Just last night, before the lights went out, I received a copy of the transcript from my hearings as part of my asylum appeal process. It is a thick stack of sheets with the transcripts of my four immigration court appearances: The first hearing took place before Crooks on May 23, the second with the same judge on June 13; the third on July 23, also before Crooks, and the fourth and final one on Sept. 18 before Cole in the Miami.

The political asylum process usually requires only three hearings, but one more was added in my case. Crooks postponed the one that should have been the last one because some of my evidence arrived late in court and neither the judge nor the government attorney had enough time to review it.

The truth is these pages summarize my life, or at least all the horrors that I experienced in Cuba because of my work as an independent journalist. As soon as I received the envelope, I began to read some parts before going to sleep, especially the judge’s decision that is the last part of the transcript. I was straining my vision too much because the dorm was already dark, but I was still able to read. My curiosity was stronger.

My emotions from that Sept. 18 returned as I read. I was reliving it all again. When I decided to stop reading, the bustle in the pod had stopped and the sleepiness that had once permeated me had completely disappeared. Now that there was finally silence, I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t stop thinking about the trial and appeal process that I face. Worry enveloped me, taking my occasional reassurance with it.

The atmosphere in the pod minutes earlier was not very calm either. A group of Cubans began to speak louder than usual and ended up singing and dancing songs of the most vulgar Cuban reggaeton. It was really rude and disrespectful. These are those moments in which I am ashamed of my compatriots: When they reveal themselves as uneducated animals, believing the world is theirs and showing off the creepiest guapería.

Almost all the Cubans who are here are of that ilk, with a few exceptions of course. The incident caused discomfort among quite a few people, especially Papa Jellow, an African gentleman who did not conceive that a few madmen would break the dorm’s usual peace.

The atmosphere became quite heated, to the point that Papa warned the officers, but they ignored him. Papa wanted to fight. He wanted to throw himself against those Cubans who insulted him by calling him “black goat” because his skin is dark like a moonless night. Other comrades, however, managed to calm him down. Starting a fight was not worth going to the hole. That was not what they wanted.

I watched everything from my bed on the second bunk. On one side were the insensitive boisterous group and Papa was on the other side with the rest of the migrants who were outraged by the Cubans’ “moment of happiness.”

I think they talked about writing a complaint against them and having everyone who agreed sign it. It was what I managed to interpret from a distance. The officer arrived a short time later to do the final court and order us that it was time to sleep. The incident fortunately resolved itself. I hope it will not be repeated tonight.

My first Thanksgiving dinner (Nov. 28, 2019)

Television for days has been bombarding me with ads for “Black Friday,” the last Friday of every November when stores offer huge discounts and savings on products of all kinds in order to stimulate sales. It is not, however, the expected Friday of consumption for which I long.

What saddens me the most is the advertising related to Thanksgiving dinner: Huge golden turkeys, pumpkin pies, mashed potatoes and hundreds and hundreds of delicious recipes for one of the U.S.’s most traditional holidays.

I do not know the origin of this celebration well, but I know that it is a time when families get together and have dinner, very similar to Christmas. Although a roasted turkey with a glass of white wine would be a huge desire for me, I would change everything for the warmth of my family, for sharing with them just an hour and heal a little of this chronic homesickness that has already accumulated for eight months.

I give myself therapy to avoid depression. I tell myself that I have never experienced “Thanksgiving” before because this holiday does not exist in Cuba. It is a 100 percent American celebration, so I better imagine that it is a day like any other, although it is extremely difficult.

We went to the yard early in the morning. We could see from inside that it was a cloudy and cold day. It started to drizzle as soon as we stepped outside, and we had to turn around and say goodbye to the outside world. I only had time to say hello to a few friends from the other pod. We talked briefly and returned to confinement. I had arranged to make a video call with Michael and say hello to his mother a few minutes before leaving.

He is visiting his family to celebrate Thanksgiving with his mother, his sister and his two little nephews. I told him while he was on his way to New Hampshire that I would love to talk to his mother, who is always worried about my situation. There was no better opportunity to greet her and we made it happen.

By the way, I practiced my English because she only knows how to say “thank you” in Spanish. It was truly an immense pleasure to talk with Michael’s mother, a very sweet woman who managed to transfer all that tenderness and kindness to her son. I told her that she should be very proud of the child he has because he is a person like few others.

The truth is that I would not know what would have become of me without the constant help and support of Michael, who has become another brother to me, because only a brother is capable of caring as much as he has.

He is my “guardian angel,” as I tell him so many times, and an adoptive member of my family forever.

“I hope that we can soon meet in person,” I said and she laughed, with the assurance that destiny had already crossed our lives. It was really exciting talking to them.

The long-awaited “Thanksgiving” dinner arrived extremely early. It was 3:30 p.m. and we already had the same old green tray in hand. The prisoners wished us, “Happy Thanksgiving” when they gave us our dinner. I honestly didn’t expect anything out of the ordinary, but I was surprised.

The tray was fuller than usual: Two pieces of a cake with white frosting and some flowers stood out. There were also sweet potatoes, a roll, and several pieces of chicken with gravy.

The dinner also came with a kind of red jelly and some beans mixed with mayonnaise. There was a puree on the bottom of the tray that nobody was really able to identify what it was. A few of us agreed that it resembled breadcrumbs, although it had a slightly sweet taste.

The truth is that it was something different to the palate that was already used to the same simple and bland food every day that is disgusting. The most delicious parts of the meal for me and for many others were the pieces of cake the prison cooks had baked. I ate a piece and kept the other and the roll for the night. hunger takes over after 8 p.m. and it is always good to have something available to ease it.

I can already say that I had my first Thanksgiving dinner, only the prison version. Hopefully next time I can treat myself with an improved version, the one that my family in Miami makes with so much love and dedication.

The call with them today was brief, just to wish them a happy dinner. My aunt and uncle were at my cousin Blanca’s house, almost ready for the celebration. I did not want to know details and they didn’t give me many, perhaps to prevent me from feeling bad, but it was inevitable. I hung up and my eyes teared up.

The move (Dec. 18, 2019)

The two touch screens in the pod flickered blue. I went to check to see if it was a message for me. I instead verified that they were for two Cubans who are not in this pod. I wasn’t sure if perhaps they would be transferred to this pod.

There had been a rumor for several days that, with fewer people in each pod, they would regroup us to fill the empty spaces and leave the dorm for only the new arrivals. It is usually a common practice. They fix a pod a bit when it’s vacated and leave it ready for the next victims.

But my predictions were wrong. An officer came in and ordered us to pack our things, because we were all going to the C-2. We didn’t understand anything. The signs said otherwise, the mandate was clear. I collected my belongings as best I could. I realized that I have too much paperwork and I probably couldn’t do it all by myself. I, however, managed.

The good news was that we would have the same beds in C-2 that we had in C-3. It was a relief, because I sleep in one of the best places: A bed next to the wall on the second tier of a three-tier bunk. It is a slightly more private place and to which very few people come.

There were some comrades when we got to C-2, which is on the opposite side of the corridor. The bulk of them had been transferred to C-1. It was clear that they wanted to clear C-3 for maintenance.

The new residence is basically the same, but we have some improvements here. There are two microwaves, tablets (an officer a few days before had removed the ones from my previous dorm due to “night noise”) and three drinking fountains from which drinking water flows. They may seem like very simple things, but any insignificant improvement can have a great impact on our lives in here.

The whole process of moving and unpacking in another “neighborhood” gave me a pounding headache that made me sick at night. Despite this, I was able to readjust quickly and a young, Latino ICE officer suddenly appeared.

A flood of questions rained down upon him as he spoke Spanish. He prepared to answer each of them because he was less elusive than the previous officers with whom we had spoken. I generally do not bother the officers because they do not usually answer my questions and only offer me evasive answers and lies.

My friend Farook from Pakistan, whose case has also been appealed, and I approached with the hope that he could provide us with new information. The officer, however, did not communicate anything to us that we did not already know. His only answer was the same as always, “We have to wait.” The appeals process takes time and those judges have to carefully review all the documentation the government and the applicants have submitted in order to issue a fair decision.

I interpreted what he said.

My answer will not arrive in December. I’m already preparing myself psychologically for it. I am implanting into my brain the prediction that I will spend the end of the year in prison. My result should arrive in January, if I’m lucky, but luck has not been a reliable ally for me. More disappointments. The headache, meanwhile, persisted, in part because my sleep the night before hadn’t been entirely pleasant.

Michael a few hours earlier had videocalled me, and told me that he was going to contact Darwin, who recently obtained asylum and is now in freedom in Colorado with his partner, who was also deserving of this country’s protection due to the death threats they received in their country for being gay.

Michael also told me that a journalist from NPR wanted to interview me to learn about my work as a journalist behind bars. I will gladly agree to speak with him. The help of colleagues is, without a doubt, crucial in this fight and will always be welcome. Michael and I, as first and foremost journalists, believe in the power of the media. That same reporter interviewed Darwin and his boyfriend in his new life outside of ICE detention centers.

A friend offered me a sleeping pill, which should relax me and make me sleep well. Drug trafficking is frequent here. Some people do not take their prescribed medication twice a day as directed and give away the rest. I had previously taken the odd sleeping pill, but I don’t like to take them for no reason because I am afraid of developing a dependency on them and then not being able to sleep on my own. I am also afraid of them because those pills nullify me as a human being.

The last time I took one I spent the day like a lazy person and could not do anything other than lay in bed. I only took half a pill this time and gave the other to a friend. I was a “drug dealer,” a highly prohibited activity, today. No one can store or share medication. The punishment can be a few days in isolation.

I couldn’t resist the headache any more, so shortly after 10 p.m. I called everyone’s attention in the new dorm to organize the next day’s cleaning shifts. I received the responsibility shortly after a Honduran named Jimmy was here. I became the new “cleaning manager” after he was deported. I was promoted to the position basically because I can speak English and Spanish so that non-Spanish speakers can understand me.

My job, in essence, is to say who should clean the dorm the next day after breakfast. We agreed that six people would be in charge of cleaning. The other day’s task would not be easy, because the move left the dorm in a mess. There was garbage everywhere. It was an intense day, in contrast to others, where monotony is the norm. That is why I do not write everyday.

Migration processes are slow and I only want to preserve in these diaries the events that really matter. By the way, I almost forgot that today it is exactly three months since I won asylum in the United States and I am still here.

Christmas, Christmas, Merry Christmas? (Dec. 24, 2019)

Christmas Eve, waiting for Christmas, did not go unnoticed, even within this confinement. Some spent the day at the microwave preparing an improved dinner that would bring them a little closer to what they used to do at home each year. I preferred not to try so hard so that the longing did not dampen my spirits too much and not to end up with my soul rotten by depression and my eyes lost in memories.

I decided to take the day as one more, although it was impossible. When I was still drowsy in the morning, the first Christmas message arrived. It was from Michael and brought tears to my cheeks and ended up permanently erasing my drowsiness. He announced that he would video call me in the afternoon. He appeared with the classic red and white hat and with his Christmas tree in the background.

It was the spitting image of a rejuvenated Santa Claus. He had a white beard, a plump face and dozens of smiles as a gift, which brought light back to my spirit. My personal version of Santa had nothing to envy the iconic character, who did not arrive with the gift for which I asked so fervently: My freedom.

Dinner, which always arrives around 4 p.m., did not make a mockery of everyday life: We only received mashed potatoes with chopped meat and chocolate pudding. I only ate half of it because my stomach is already adjusted to a baby’s diet. The other portion would be to annihilate hunger shortly before going to sleep. The only thing that made my Christmas Eve dinner different was a soda named “Arctic Rain.”

I bought it in the morning at the commissary with the idea that it would “color” Bossier’s boring flavors a little more. I missed how the bubbles tickle my throat. It was, however, a bad investment.

That green bottle filled my mouth with a taste of medicine rather than a drink. The drink was also like a fizzy laxative that was hot, because there was no ice. I shared it with my friends Erick and Jorge, who sat next to me for dinner almost every night. They took a sip more out of curiosity than wishful thinking.

There was a whole banquet for the occasion a few steps away at the other end of the long metal table. Several Cubans worked together to cook rice with mortadella, cheese-filled tacos, and rice with beans. There were also cookies and a custard-coated chocolate pudding that had “happy” written across the top.

It was by far the biggest dinner I have seen at Bossier and it was immortalized with a photo through a video call with a family member. That is the only way to keep a photographic memory inside this prison. We can receive photos attached to text messages through tablets, but we cannot send anything. This “privilege” clashes with prison policies, which prevent the release of images from inside the facility.

Prisons in all parts of the world are an unknown world, a deep hole that the media cameras cannot fully reach. Only those who have experienced it themselves will be able to describe them with certainty.

When I thought that the day would not bring me any surprises, I received a message from my aunt asking me to make a video call. I have only seen my family on two previous occasions since I have been in the United States: Once with Michael’s help and the other with that of a cousin, who again made this longed-for reunion a reality.

My aunt and uncle appeared before me, like a Christmas miracle, dressed with loving smiles. They had already eaten. There was really no party, just a small family gathering. The real celebration, they said, would be when I was with them in Miami. It was truly a delightful moment, which led to a stroke of homesickness for not being with them.

I did not want to call Cuba, because neither my mother nor my brother deserve to be infected with the bitterness that inhabits my soul. My younger brother’s Birthday is in two days and I will take the opportunity to hear from them then. The Cubans at night began to sing loudly while hitting some drawers like percussion instruments.

Delfin, a Cuban who we call that because he has a dolphin tattooed on his ribs, climbed on a bed for a few seconds and rhythmically shook his waist.

“All the way down, all the way down!” he said, eager for the crowd to party with him.

Delfin climbed onto the bed and raised his hands in a dancing outburst, which only lasted a few seconds. It was enough for the officers to lead him to the hole. They took him away as he was, shirtless. The officers turned off the lights to drown out that “uproar” of prison order.

The next day, Christmas lunch came with a prisoner who had a nylon bag on his back. He was our Santa, but he didn’t say “ho ho ho” as he gave us the tray. He instead gave us a pair of socks and a pin, which turned out to be a fabulous treat.

“Merry Christmas,” the Santa of Bossier wished me when I passed him.

He did not come with his sleigh, nor with his reindeer and his classic wardrobe, but he brought the most important thing. I saw in his eyes a spirit of kindness that is unusual in this place and that I definitely did not expect.

Death of the old year and birth of the new one (Dec. 31, 2019 – Jan. 1, 2020)

My comrades from the very dawn of the 31st woke up in a festive spirit. There was already an enthusiastic group of pastry chefs around the microwave preparing sweets, because it takes the most time. Rice pudding and various puddings were born out of that end-of-year culinary devotion. The hustle and bustle in the pod “kitchen” continued throughout the day.

Today is commissary day and I was fortunately able to stock up on what I needed for the last dinner of 2019. My expectations were not as ambitious as those of others, but I however wanted to taste something different. I deserved it.

Two Cuban friends called my name as I was walking through the dorm. They were taking “a few drinks” from alcohol wipes used to clean wounds. They wanted me to read the case to see if they were not going to die guzzling that. I didn’t understand at first until I saw them chewing on those alcohol-soaked pieces of paper.

It was a lot of fun watching them try to extract the alcohol from those pieces of paper. I told them that nothing was going to happen to them, although they had called me over a little late because they had already become “tipsy.”

“Want one? It’s strong, it’s like a double vodka,” my friend Yosiel asked me.

I appreciated the offer, but did not drink it. I don’t have much tolerance for strong drinks. I then remembered I had a jar with fruit that I had stored in it for several months. The fruit over time ferment and give off alcohol. Chunks of pineapple, papaya and pear add a tropical flavor to the preparation. The result is a primitive wine, completely handmade, the product of prison inventiveness.

We had already tried it a few weeks before and it tasted delicious. I felt it was even half carbonated. It ran down my throat like a refreshing nectar, which also gave me a headache, because maybe I drank it like water and I haven’t had any drinks for a long time, so my tolerance for alcohol has decreased. They say that sweet and unrefined drinks are the fastest way to get drunk.

The wine was bubbly, as if it had a life of its own, when opened. The aged mixture gave off a strong smell of alcohol. I stirred it a bit and hid it again. Making this concoction is another of the many prohibitions that could take me to the hole for several days, so all precautions must be taken so they won’t find it.

Throughout the course of the day I kept memories from invading my mind, a task at which I failed miserably. Each remembrance was a merciless sting that I inflicted on myself, especially when I learned that my father had traveled to Cuba for the occasion after several years away during this time of the year. The only thing missing was me in my little family, which grew because my aunt and cousins from Havana had visited for the first time in a long time.

They would go to celebrate the new year at an uncle’s house with a roasted pig and music. My mind wanted to avoid all that, but my masochistic heart insisted on imagining that family reunion that many times I did not like at all. I missed it today without question.

The smell of burning bologna in the microwave brought me back. I prepared rice with it and added corn, pork, barbecue sauce and mayonnaise to it. That was the filling for 12 burritos that I shared with two Ecuadorian friends and a Honduran.

The New Year’s Eve concert in Times Square enlivened the dinner and a brief tag team tournament in which I was shamefully beaten followed. I consoled myself after the fiasco by saying, “Lucky in the game, unlucky in love.” That silly phrase tries to cheer up the loser’s spirit, but I then remembered I have not been very happy in love either.

We were all in our beds at 11 p.m. by order of the officer on duty, who passed the list with the intention of ruining the welcome of the new year even more.

The spoiler, however, failed to destroy the feeling of celebration. Many sang parts of current and classic Cuban musical genres at the top of their lungs while sitting on their beds. We even sang parts of Cuba’s National Anthem.

Cubans are the only ones who are capable of chasing away sadness and finding a moment of joy in such adversity. Officers made their rounds and unexpectedly went hunting for someone who was not in their place. We saw through the windows how several comrades from other dorms were on their way to the hole. They would welcome 2020 in a cold isolation cell. There is no mercy here, even on Dec. 31. Luckily no one in C-2 was taken there.

It was difficult for us to pinpoint the new year’s arrival because we did not have tablets. The few that remained were removed before the improvised singers’ insistent chorus.

Juan, a Honduran, suddenly announced it was already after midnight and we all melted into a collective hug. They turned on the lights and the deputies surprised us by shaking hands amid congratulations and excitement.

“Happy New Year,” said the officers and they immediately removed the two microwaves for “insubordination.”

Nobody cared about that and we even celebrated it with more intensity. They couldn’t take more than 70 people to the hole, so they had to punish us in some way. That tiny moment of happiness for the new year was forbidden.

A Cuban after he returned to bed dumped a glass of water on the floor, a tradition that millions of Cubans carry out when they welcome the new year with a bucket of water outside their homes. The liquid, it is believed, takes away with it all bad omens and welcomes the next 365 days “clean” of all evil.

The Muslims began their prayers at midnight. A Pakistani on one side of my bed was kneeling on his knees as he prayed to Allah amid intense sobs. His first thoughts of the new year were for his God to whom he prays with devotion several times every day.

Already lying in my “residence,” I marked with a cross on the 31st on the calendar that I have pasted on the bottom of the bed that is above mine. I took it off and put it under the mattress to archive 2019, a year that will remain forever in my memory.

I only asked my saints for freedom and the possibility of living in this country without the threats and persecution that awaits me in Cuba if I am deported.

The first day of January, on the other hand, arrived more calmly than usual. The television did not turn on, which was also part of the collective punishment for our “party” last night. Smiles nevertheless appeared on the faces of many when a video revealed that a Honduran friend had become a father.

Many quickly crowded around to admire the first images of the newborn, who knew her father through a cold and impersonal screen. She still cannot recognize him, nor will she soon feel the warmth of her father, who has already been deported to Honduras. ICE separated this young family, as it has done with thousands of others, upon his arrival in the United States. His girlfriend, who was already pregnant with her baby, received a ticket home while he was confined in Louisiana, where he did not receive bail or parole and lost his asylum case.

The father smiles proudly in front of the screen. It is impossible for him to hide his joy from her at such a time. Nothing and no one will ever be able to steal that happiness from him thinking about his daughter, even from a distance.

A new ‘home’ awaits me (Jan. 10, 2020)

An ICE official who addressed us in Spanish confirmed one of the many rumors that had been circulating in Bossier in recent days.

“Your companions are being transferred to another detention center and soon you will too, because this facility will be closed for remodeling,” the officer said in front of the few of us who were left in this dorm.

At least I received the news with joy. My 8-month stay in this prison demolished my illusions and took away a bit of my innocence. It transformed me into a much stronger human being, capable of withstanding very cruel scenarios that I did not believe I was capable of overcoming.

I guess that’s the only thing I have to thank for this experience, that layer of firmness that has taken over my spirit. Bossier’s positive side is not very extensive aside from the friends I’ve made and the books I’ve read.

The $.09 that remained in my account was reduced to zero on the night of Jan. 8. It was the definitive signal that I would be transferred to another facility together with 48 other comrades. Only a few who were left in the dorm would then follow us on that Bossier escape plan.

I was told to pack, a moment for which I had waited too long, the next morning, although I hoped it would have been different. I imagined my departure from here would mean my definitive freedom and not continued incarceration, but life would not have it. The fight continues and I must accept it.

Transfers are quite exhausting with too much paperwork that is as complex as a move in Cuba. Bureaucracy is a global evil that does not discriminate in political systems. They stripped us of this prison’s wardrobe, that horrible garish yellow uniform, and we dressed in the clothes we brought.

We also delivered the few belongings that are property of the prison: Mattress, sheets, towels, bedspread and everything that we do not want to take with us. And they then gave us our luggage.

I was ready for the last step in the process — getting my hands and feet handcuffed — when the prison warden entered the pod where we were meeting. Some had trashed the empty pod to which they had led us a few minutes earlier. He flew into a rage when he saw that, and he ordered us to clean up the mess. I thought it was fair, even though I hadn’t taken part in it. I will never forget his final words to us.

“You are animals. Go back to your countries, human shit!” he said.

The restrained and even understanding posture that he had shown me collapsed in that sentence full of hatred and racism. I could, at last, clearly see the real man who lived under that sheriff’s uniform. He no longer had to keep pretending kindness. He missed the $67 a day that ICE paid him for each of us. Anyone would be upset, but nothing justified his overbearing and boorish behavior.

The cold bite of the handcuffs, that metal that captures me like a dangerous criminal, is one of the transfer’s worst moments. They tied around my waist a chain that limits the movement of my hands and produces a high-pitched jingle that can be heard from several meters away. Walking with your hands handcuffed and feet shackled resembles ducks’ gait, slow and swaying from side to side, measuring every inch to avoid falling.

A young Bossier officer, one of the few who treated us with respect, told us the journey would take about four hours. We would go further into southern Louisiana.

“I’ll miss you all,” he told us in the hallway on the way out.

There was also Martha, a nurse of Mexican descent, who wished us good luck as we walked in front of her. I did not know whether her words were sincere or were wrapped in hypocrisy.

We were luckily transferred in a comfortable bus. A hard iron surface was the seat in the other one. There was no place for comfort. They were two white buses, which started their route just after 9 a.m.

Going out into the outside world again was like the first walk of a newborn who admires with amazement everything that is within his reach and life seems like a magical invention. Nobody wanted to miss the landscape, dotted by some small towns where the Christmas decorations still remained. Forests, however, dominated both sides of the road with bare trees, stripped of their foliage because of the mild Southern winter.

It was an unprecedented landscape before my eyes, because nature in Cuba only loses its greenness when drought devours it. The pine trees were the only ones that remained alive, like glimpses of life in the middle of a gloomy forest.

Fatigue at times overcame me and I, together with my comrades, managed to recover a bit of the morning’s lost sleep. The highway crossed two huge rivers that looked like seas, gas stations, McDonald’s, hotels, hospitals, and hundreds of billboards that bombarded me with forbidden culinary delights. I remember my time in Jena, the city where the court is, and another tiny town called Monroe.

With each minute that I advanced further into the bowels of Louisiana, the strange feeling grew within me that if we got lost no one would be able to find us. I saw a great expanse. It looked like a field for crops and I could see an installation in the distance.

A factory, I thought. To my surprise, however, it was my destination. I was again in the middle of nowhere. A blue sign identified it as the River Correctional Center, our next “home.” The handcuffs were already starting to hurt my wrists, but this would be over soon. My new home awaited me. They opened the entrance gate and the two buses cautiously entered.

The White House

Four states to ignore new Title IX rules protecting transgender students

Biden administration last Friday released final regulations

BY ERIN REED | Last Friday, the Biden administration released its final Title IX rules, which include protections for LGBTQ students by clarifying that Title IX forbids discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

The rule change could have a significant impact as it would supersede bathroom bans and other discriminatory policies that have become increasingly common in Republican states within the U.S.

As of Thursday morning, however, officials in at least four states — Oklahoma, Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina — have directed schools to ignore the regulations, potentially setting up a federal showdown that may ultimately end up in a protracted court battle in the lead-up to the 2024 elections.

Louisiana State Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley was the first to respond, decrying the fact that the new Title IX regulations could block teachers and other students from exercising what has been dubbed by some a “right to bully” transgender students by using their old names and pronouns intentionally.

Asserting that Title IX law does not protect trans and queer students, Brumley states that schools “should not alter policies or procedures at this time.” Critically, several courts have ruled that trans and queer students are protected by Title IX, including the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in a recent case in West Virginia.

In South Carolina, Schools Supt. Ellen Weaver wrote in a letter that providing protections for trans and LGBTQ students under Title IX “would rescind 50 years of progress and equality of opportunity by putting girls and women at a disadvantage in the educational arena,” apparently leaving trans kids out of her definition of those who deserve progress and equality of opportunity.

She then directed schools to ignore the new directive while waiting for court challenges. While South Carolina does not have a bathroom ban or statewide “Don’t Say Gay or Trans” law, such bills continue to be proposed in the state.

Responding to the South Carolina letter, Chase Glenn of Alliance For Full Acceptance stated, “While Supt. Weaver may not personally support the rights of LGBTQ+ students, she has the responsibility as the top school leader in our state to ensure that all students have equal rights and protections, and a safe place to learn and be themselves. The flagrant disregard shown for the Title IX rule tells me that our superintendent unfortunately does not have the best interests of all students in mind.”

Florida Education Commissioner Manny Diaz also joined in instructing schools not to implement Title IX regulations. In a letter issued to area schools, Diaz stated that the new Title IX regulations were tantamount to “gaslighting the country into believing that biological sex no longer has any meaning.”

Governor Ron DeSantis approved of the letter and stated that Florida “will not comply.” Florida has notably been the site of some of the most viciously anti-queer and anti-trans legislation in recent history, including a “Don’t Say Gay or Trans” law that was used to force a trans female teacher to go by “Mr.”

State Education Supt. Ryan Walters of Oklahoma was the latest to echo similar sentiments. Walters has recently appointed the right-wing media figure Chaya Raichik of Libs of TikTok to an advisory role “to improve school safety,” and notably, Raichik has posed proudly with papers accusing her of instigating bomb threats with her incendiary posts about LGBTQ people in classrooms.

The Title IX policies have been universally applauded by large LGBTQ rights organizations in the U.S. Lambda Legal, a key figure in fighting anti-LGBTQ legislation nationwide, said that the regulations “clearly cover LGBTQ+ students, as well as survivors and pregnant and parenting students across race and gender identity.” The Human Rights Campaign also praised the rule, stating, “rule will be life-changing for so many LGBTQ+ youth and help ensure LGBTQ+ students can receive the same educational experience as their peers: Going to dances, safely using the restroom, and writing stories that tell the truth about their own lives.”

The rule is slated to go into effect Aug. 1, pending any legal challenges.

****************************************************************************

Erin Reed is a transgender woman (she/her pronouns) and researcher who tracks anti-LGBTQ+ legislation around the world and helps people become better advocates for their queer family, friends, colleagues, and community. Reed also is a social media consultant and public speaker.

******************************************************************************************

The preceding article was first published at Erin In The Morning and is republished with permission.

Pennsylvania

Malcolm Kenyatta could become the first LGBTQ statewide elected official in Pa.

State lawmaker a prominent Biden-Harris 2024 reelection campaign surrogate

Following his win in the Democratic primary contest on Wednesday, Pennsylvania state Rep. Malcolm Kenyatta, who is running for auditor general, is positioned to potentially become the first openly LGBTQ elected official serving the commonwealth.

In a statement celebrating his victory, LGBTQ+ Victory Fund President Annise Parker said, “Pennsylvanians trust Malcolm Kenyatta to be their watchdog as auditor general because that’s exactly what he’s been as a legislator.”

“LGBTQ+ Victory Fund is all in for Malcolm, because we know he has the experience to win this race and carry on his fight for students, seniors and workers as Pennsylvania’s auditor general,” she said.

Parker added, “LGBTQ+ Americans are severely underrepresented in public office and the numbers are even worse for Black LGBTQ+ representation. I look forward to doing everything I can to mobilize LGBTQ+ Pennsylvanians and our allies to get out and vote for Malcolm this November so we can make history.”

In April 2023, Kenyatta was appointed by the White House to serve as director of the Presidential Advisory Commission on Advancing Educational Equity, Excellence and Economic Opportunity for Black Americans.

He has been an active surrogate in the Biden-Harris 2024 reelection campaign.

The White House

White House debuts action plan targeting pollutants in drinking water

Same-sex couples face higher risk from environmental hazards

Headlining an Earth Day event in Northern Virginia’s Prince William Forest on Monday, President Joe Biden announced the disbursement of $7 billion in new grants for solar projects and warned of his Republican opponent’s plans to roll back the progress his administration has made toward addressing the harms of climate change.

The administration has led more than 500 programs geared toward communities most impacted by health and safety hazards like pollution and extreme weather events.

In a statement to the Washington Blade on Wednesday, Brenda Mallory, chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality, said, “President Biden is leading the most ambitious climate, conservation, and environmental justice agenda in history — and that means working toward a future where all people can breathe clean air, drink clean water, and live in a healthy community.”

“This Earth Week, the Biden-Harris Administration announced $7 billion in solar energy projects for over 900,000 households in disadvantaged communities while creating hundreds of thousands of clean energy jobs, which are being made more accessible by the American Climate Corps,” she said. “President Biden is delivering on his promise to help protect all communities from the impacts of climate change — including the LGBTQI+ community — and that we leave no community behind as we build an equitable and inclusive clean energy economy for all.”

Recent milestones in the administration’s climate policies include the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s issuance on April 10 of legally enforceable standard for detecting and treating drinking water contaminated with polyfluoroalkyl substances.

“This rule sets health safeguards and will require public water systems to monitor and reduce the levels of PFAS in our nation’s drinking water, and notify the public of any exceedances of those levels,” according to a White House fact sheet. “The rule sets drinking water limits for five individual PFAS, including the most frequently found PFOA and PFOS.”

The move is expected to protect 100 million Americans from exposure to the “forever chemicals,” which have been linked to severe health problems including cancers, liver and heart damage, and developmental impacts in children.

An interactive dashboard from the United States Geological Survey shows the concentrations of polyfluoroalkyl substances in tapwater are highest in urban areas with dense populations, including cities like New York and Los Angeles.

During Biden’s tenure, the federal government has launched more than 500 programs that are geared toward investing in the communities most impacted by climate change, whether the harms may arise from chemical pollutants, extreme weather events, or other causes.

New research by the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law found that because LGBTQ Americans are likelier to live in coastal areas and densely populated cities, households with same-sex couples are likelier to experience the adverse effects of climate change.

The report notes that previous research, including a study that used “national Census data on same-sex households by census tract combined with data on hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) from the National Air Toxics Assessment” to model “the relationship between same-sex households and risk of cancer and respiratory illness” found “that higher prevalence of same-sex households is associated with higher risks for these diseases.”

“Climate change action plans at federal, state, and local levels, including disaster preparedness, response, and recovery plans, must be inclusive and address the specific needs and vulnerabilities facing LGBT people,” the Williams Institute wrote.

With respect to polyfluoroalkyl substances, the EPA’s adoption of new standards follows other federal actions undertaken during the Biden-Harris administration to protect firefighters and healthcare workers, test for and clean up pollution, and phase out or reduce use of the chemicals in fire suppressants, food packaging, and federal procurement.

-

State Department4 days ago

State Department4 days agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

South America2 days ago

South America2 days agoArgentina government dismisses transgender public sector employees

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoCatching up with the asexuals and aromantics of D.C.

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoSmithsonian staff concerned about future of LGBTQ programming amid GOP scrutiny