World

Honduras government institutions ‘are murdering us’

Lack of opportunities, violence prompt LGBTQ people to migrate

Editor’s note: International News Editor Michael K. Lavers was on assignment for the Washington Blade in Honduras, El Salvador and Mexico from July 11-25.

LA CEIBA, Honduras — Leonela and Jerlín, her partner of 11 years, and their school-age daughter live in La Ceiba, a city on Honduras’ Caribbean coast.

Jerlín was a bus driver in San Pedro Sula, the country’s commercial capital, until gang members shot him three times in 2012 because he couldn’t pay the extortion money from which they demanded from him each month. Jerlín, Leonela and their daughter subsequently fled to La Ceiba, which is about three hours east of San Pedro Sula.

“We left,” Jerlín told the Washington Blade on July 20 during an interview at the offices of Organización Pro Unión Ceibeña (Oprouce), a La Ceiba-based advocacy group. “We fled from there.”

Jerlín migrated to Mexico in January 2019, but returned to Honduras less than a month later because Leonela was in the hospital. The couple and their daughter migrated to Mexico a year later.

Leonela asked for a Mexican humanitarian visa for her and her daughter once they arrived in Ciudad Hidalgo, a Mexican border city that is across the Suchiate River from Tecún Umán, Guatemala.

Leonela told the Blade that she planned to ask for asylum in Mexico and wanted to go to Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the capital of Mexico’s Chiapas state, to find work. Leonela said she and Jerlín instead decided to return to Honduras because they did not want their daughter to further endure the “inhumane” conditions of the migrant detention center in Tapachula, a city that is roughly 20 miles northwest of Ciudad Hidalgo, in which they were living.

“We decided it was better to allow them to deport us,” said Jerlín.

Jerlín, Leonela and their daughter returned to Honduras in May 2020. Someone shot at their house on July 10, 2020.

“They couldn’t even do what people wanted them to do, perhaps even buring us alive,” said Leonela.

Leonela and Jerlín are among the many LGBTQ Hondurans who have decided to leave Honduras in order to escape violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Vice President Kamala Harris and other Biden administration officials have acknowledged anti-LGBTQ violence is one of the “root causes” of migration from Honduras and neighboring Guatemala and El Salvador.

Title 42, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rule that closed the Southern border to most asylum seekers and migrants because of the coronavirus pandemic, remains in place. The White House has repeatedly told migrants not to travel to the U.S.

Roxsana Hernández, a trans Honduran woman with HIV, died at a New Mexico hospital on May 25, 2018, while in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody.

Natasha, another trans Honduran woman, arrived in Matamoros, a Mexican border city that is across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas, on Oct. 12, 2019. The previous administration forced her to pursue her U.S. asylum case in Mexico under its Migrant Protection Protocols. (The U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday ordered the Biden administration to reinstate MPP.)

The Blade interviewed Natasha on Feb. 27 at a Matamoros shelter that Rainbow Bridge Asylum Seekers, a program for LGBTQ asylum seekers and migrants that Resource Center Matamoros, a group that provides assistance to asylum seekers and migrants in the Mexican border city, helped create. The U.S. less than two weeks later allowed Natasha to enter the country.

Oprouce Executive Director Sasha Rodríguez, who is trans, has participated in the State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program.

She said a lack of employment and housing associated with the pandemic has prompted more Hondurans to migrate to the U.S., Mexico and Costa Rica. Rodríguez also told the Blade the U.S. and “our countries sell an American dream that doesn’t exist.”

“Why don’t these American organizations say don’t go,” she said, specifically referring to trans people who have decided to leave Honduras. “Here they see it as beautiful. They are already in the United States, but they were raped while trying to get there. They were kidnapped.”

Alexa, a 27-year-old trans woman from La Ceiba, told the Blade she has friends who live in Mexico. Alexa said she would like to leave Honduras, but she doesn’t want to leave her mother alone.

“I don’t want to leave her alone and abandon her because I have always fought for her,” Alexa told the Blade during an interview at Oprouce. “She supports me as a woman.”

Alexa said she served a nearly 3-year prison sentence for attempted murder, even though she was defending herself against a woman who was hitting her in the face with a rock. Alexa began to sob when she started to tell the Blade about the Salvadoran man who raped her in prison. She said the warden then forced her to cut her hair and guards doused her with “ice cold water” in an isolation cell.

“I was a woman,” said Alexa. “They made me a man.”

Alexa told the Blade that other prisoners tried to kill her. She said she also tried to die by suicide several times until her release on Jan. 27.

Alexa said she has not been able to find a job since she left prison. She also told the Blade that gang members continue to threaten her.

“It is sometimes very difficult to lead the lifestyle that we lead as trans women in Honduras,” she said, referring to anti-trans discrimination and a lack of employment opportunities.

Venus, a 30-year-old trans woman who is also from La Ceiba, echoed Alexa.

“To be a trans person is synonymous with teasing, harassment, violence and even death,” Venus told the Blade at Oprouce.

Venus said Honduran soldiers regularly attack trans women. She told the Blade a lack of access to health care, machismo and patriarchal attitudes are among the myriad other issues that she and other trans Hondurans face.

“We don’t have access to education, to health (care), to a job,” said Venus. “Above all we are fighting for a gender-based law that recognizes us as women and men.”

Venus added she, like Alexa, would leave Honduras “if I was given the opportunity to do so.”

Landmark ruling finds Honduras responsible for trans woman’s murder

Red Lésbica Cattrachas, a lesbian feminist human rights group based in Tegucigalpa, the Honduran capital, notes 373 LGBTQ Hondurans were reported killed in the country between 2009-2020.

Statistics indicate 119 of those murdered were trans. Red Lésbica Cattrachas also noted 18 of the LGBTQ Hondurans who were reported killed were in Atlántida department in which La Ceiba is located.

Vicky Hernández was a trans activist and sex worker with HIV who worked with Colectivo Unidad Color Rosa, a San Pedro Sula-based advocacy group.

Hernández’s body was found in a San Pedro Sula street on June 29, 2009, hours after the coup that ousted then-President Manuel Zelaya from power. Hernández and two other trans women the night before ran away from police officers who tried to arrest them because they were violating a curfew.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights in June issued a landmark ruling that found Honduras responsible for Hernández’s murder.

The ruling ordered Honduras to pay reparations to Hernández’s family and enact laws that protect LGBTQ people from violence and discrimination. The government of President Juan Orlando Hernández, whose brother, former Congressman Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, is serving a life sentence in the U.S. after a federal jury convicted him of trafficking tons of cocaine into the country, has not publicly responded to the ruling.

Rodríguez noted to the Blade that Oprouce and other advocacy groups have been fighting for a trans rights law in Honduras for more than a decade.

“We have had failure for 11 years, but I think that with what happened with the Inter-American Court, the recommendations that have come from the Vicky Hernández case could achieve something important,” said Rodríguez. “There are very good human rights recommendations for Honduras and there are good recommendations that Honduras could automatically apply to trans women.”

Rodríguez as she discussed the ruling reiterated trans Hondurans continue to face violence, discrimination and a lack of employment opportunities. Rodríguez also reiterated her sharp criticism of her country’s government and its institutions.

“Societal exclusion forces us to do sex work,” she said. “We are being harmed by our trade: Murder, persecution, hate crimes, torture, beatings.”

“I always say that it is an institutional death because state institutions are murdering us,” added Rodríguez.

‘My fight is here’

In spite of these challenges, Rodríguez said there has been progress.

Oprouce — which works on a variety of issues that include the prevention of gender-based violence and fighting HIV/AIDS — offers workshops to the Public Ministry, the Honduran Armed Forces and judges. Asociación de Prevención y Educación en Salud, Sexualidad, Sida y Derechos Humanos (Aprest), another advocacy group in Tela, a city that is about 60 miles west of La Ceiba, conducts similar trainings with local and national authorities.

Aprest Executive Director Leonel Barahona Medina told the Blade during an interview at a beachfront restaurant in Tela on July 20 that city officials have given him an office from which he and his colleagues can work. Barahona said they also supported activists who raised the Pride flag on June 27 in front of Tela City Hall.

A similar ceremony took place in a park in the center of La Ceiba.

“We have good relations with them,” said Barahona, referring to Tela officials.

Both Barahona and Rodríguez said their work will continue.

“My fight is here,” said Rodríguez. “My essence and my dreams are here.”

Abdiel Echevarría-Caban and Reportar sin Miedo contributed to this story.

Ecuador

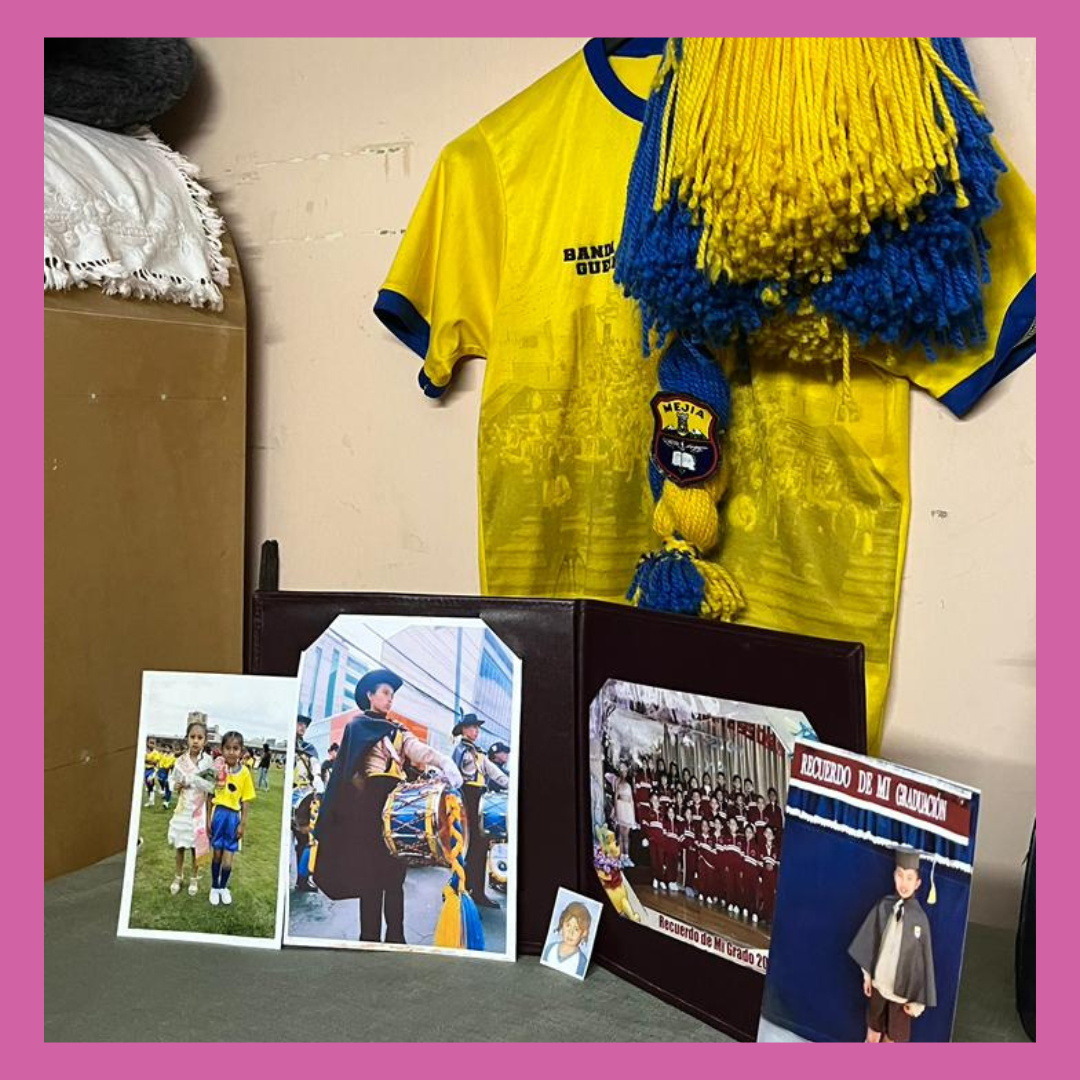

Justicia reconoce delito de odio en caso de bullying en Instituto Nacional Mejía de Ecuador

Johana B se suicidó el 11 de abril de 2023

A casi tres años del suicidio de Johana B., quien estudió en el Instituto Nacional Mejía, colegio emblemático de Quito, el Tribunal de la Corte Nacional de Justicia ratificó la condena para el alumno responsable del acoso escolar que la llevó a quitarse la vida.

Según información de la Fiscalía, el fallo de última instancia deja en firme la condena de cuatro años de internamiento en un centro para adolescentes infractores, en una audiencia de casación pedida por la defensa del agresor, tres meses antes de que prescriba el caso.

Con la sentencia, este caso es uno de los primeros en el país en reconocer actos de odio por violencia de género, delito tipificado en el artículo 177 del Código Orgánico Penal Integral (COIP).

El suicidio de Johana B. ocurrió el 11 abril de 2023 y fue consecuencia del acoso escolar por estereotipos de género que enfrentó la estudiante por parte de su agresor, quien constantemente la insultaba y agredía por su forma de vestir, llevar el cabello corto o practicar actividades que hace años se consideraban exclusivamente para hombres, como ser mando de la Banda de Paz en el Instituto Nacional Mejía.

Desde la muerte de Johana, su familia buscaba justicia. Su padre, José, en una entrevista concedida a edición cientonce para la investigación periodística Los suicidios que quedan en el clóset a causa de la omisión estatal afirmó que su hija era acosada por su compañero y otres estudiantes con apodos como “marimacha”, lo que también fue corroborado en los testimonios recogidos por la Unidad de Justicia Juvenil No. 4 de la Fiscalía.

Los resultados de la autopsia psicológica y del examen antropológico realizados tras la muerte de Johana confirmaron las versiones de sus compañeras y docentes: que su agresor la acosó de manera sistemática durante dos años. Los empujones, jalones de cabello o burlas, incluso por su situación económica, eran constantes en el aula de clase.

La violencia que recibió Johana escaló cuando su compañero le dio un codazo en la espalda ocasionándole una lesión que le imposibilitó caminar y asistir a clases.

Días después del hecho, la adolescente se quitó la vida en su casa, tras escuchar que la madre del agresor se negó a pagar la mitad del valor de una tomografía para determinar la lesión en su espalda, tal como lo había acordado previamente con sus padres y frente al personal del DECE (Departamento de Consejería Estudiantil del colegio), según versiones de su familia y la Fiscalía.

#AFONDO | Johana se suicidó el 11 de abril de 2023, tras ser víctima de acoso escolar por no cumplir con estereotipos femeninos 😢.

Dos semanas antes, uno de sus compañeros le dio un codazo en la espalda, ocasionándole una lesión que le imposibilitó caminar 🧵 pic.twitter.com/bXKUs9YYOm

— EdicionCientonce (@EdCientonce) September 3, 2025

“Era una chica linda, fuerte, alegre. Siempre nos llevamos muy bien, hemos compartido todo. Nos dejó muchos recuerdos y todos nos sentimos tristes; siempre estamos pensando en ella. Es un vacío tan grande aquí, en este lugar”, expresó José a Edición Cientonce el año pasado.

Para la fiscal del caso y de la Unidad de Justicia Juvenil de la Fiscalía, Martha Reino, el suicidio de la adolescente fue un agravante que se contempló durante la audiencia de juzgamiento de marzo de 2024, según explicó a este medio el año pasado. Desde entonces, la familia del agresor presentó un recurso de casación en la Corte Nacional de Justicia, que provocó la dilatación del proceso.

En el fallo de última instancia, el Tribunal también dispuso que el agresor pague $3.000 a la familia de Johana B. como reparación integral. Además, el adolescente deberá recibir medidas socioeducativas, de acuerdo al artículo 385 del Código Orgánico de la Niñez y Adolescencia, señala la Fiscalía.

El caso de Johana también destapó las omisiones y negligencias del personal del DECE y docentes del Instituto Nacional Mejía. En la etapa de instrucción fiscal se comprobó que no se aplicaron los protocolos respectivos para proteger a la víctima.

De hecho, la Fiscalía conoció el caso a raíz de la denuncia que presentó su padre, José, y no por el DECE, aseguró la fiscal el año pasado a Edición Cientonce.

Pese a estas omisiones presentadas en el proceso, el fallo de última instancia sólo ratificó la condena para el estudiante.

Africa

LGBTQ groups question US health agreements with African countries

Community could face further exclusion, government-sanctioned discrimination

Some queer rights organizations have expressed concern that health agreements between the U.S. and more than a dozen African countries will open the door to further exclusion and government-sanctioned discrimination.

The Trump-Vance administration since December has signed five-year agreements with Kenya, Uganda, and other nations that are worth a total of $1.6 billion.

Kenyan and Ugandan advocacy groups note the U.S. funding shift from NGO-led to a government-to-government model poses serious risks to LGBTQ people and other vulnerable populations in accessing healthcare due to existing discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Uganda Minority Shelters Consortium, Let’s Walk Uganda, the Kenya Human Rights Commission, and the Center for Minority Rights and Strategic Litigation note the agreements’ silence on vulnerable populations in accessing health care threatens their safety, privacy, and confidentiality.

“Many LGBTQ persons previously accessed HIV prevention and treatment, sexual and reproductive health services, mental health support, and psychosocial care through specialized clinics supported by NGOs and partners such as USAID (the U.S. Agency for International Development) or PEPFAR,” Let’s Walk Uganda Executive Director Edward Mutebi told Washington Blade.

He noted such specialized clinics, including the Let’s Walk Medical Center, are trusted facilities for providing stigma-free services by health workers who are sensitized to queer issues.

“Under this new model that sidelines NGOs and Drop-in Centers (DICs), there is a high-risk of these populations being forced into public health facilities where stigma, discrimination, and fear of exposure are prevalent to discourage our community members from seeking care altogether, leading to late testing and treatment,” Mutebi said. “For LGBTQ persons already living under criminalization and heightened surveillance, the loss of community-based service delivery is not just an access issue; it is a full-blown safety issue.”

Uganda Minority Shelters Consortium Coordinator John Grace said it is “deeply troubling” for the Trump-Vance administration to sideline NGOs, which he maintains have been “critical lifelines” for marginalized communities through their specialized clinics funded by donors like the Global Fund and USAID.

USAID officially shut down on July 1, 2025, after the White House dismantled it.

Grace notes the government-to-government funding framework will impact clinics that specifically serve the LGBTQ community, noting their patients will have to turn to public systems that remain inaccessible or hostile to them.

“UMSC is concerned that the Ugandan government, under this new arrangement, may lack both the political will and institutional safeguards to equitably serve these populations,” Grace said. “Without civil society participation, there is a real danger of invisibility and neglect.”

Grace also said the absence of accountability mechanisms or civil society oversight in the U.S. agreement, which Uganda signed on Dec. 10, would increase state-led discrimination in allocating health resources.

Center for Minority Rights and Strategic Litigation Legal Manager Michael Kioko notes the U.S. agreement with Kenya, signed on Dec. 4, will help sustain the country’s health sector, but it has a non-binding provision that allows Washington to withdraw or withhold the funding at any time without legal consequences. He said it could affect key health institutions’ long-term planning for specialized facilities for targeted populations whose independent operations are at stake from NGOS the new agreement sidelines.

“The agreement does not provide any assurance that so-called non-core services, such as PrEP, PEP, condoms, lubricants, targeted HIV testing, and STI prevention will be funded, especially given the Trump administration’s known opposition to funding these services for key populations,” Kioko said.

He adds the agreement’s exclusionary structure could further impact NGO-run clinics for key populations that have already closed or scaled down due to loss of the U.S. funding last year, thus reversing hard-won gains in HIV prevention and treatment.

“The socio-political implications are also dire,” Kioko said. “The agreement could be weaponized to incite discrimination and other LGBTQ-related health issues by anti-LGBTQ voices in the parliament who had called for the re-authorization of the U.S. funding (PEPFAR) funding in 2024, as a political mileage in the campaign trail.”

Even as the agreement fails to safeguard specialized facilities for key populations, the Kenya Human Rights Commission states continued access to healthcare services in public facilities will depend on the government’s commitment to maintain confidentiality, stigma-sensitive care, and targeted outreach mechanisms.

“The agreement requires compliance with applicable U.S. laws and foreign assistance policies, including restrictions such as the Helms Amendment on abortion funding,” the Kenya Human Rights Commission said in response to the Blade. “More broadly, funded activities must align with U.S. executive policy directives in force at the time. In the current U.S. context, where executive actions have narrowed gender recognition and reduced certain transgender protections, there is a foreseeable risk that funding priorities may shift.”

Just seven days after Kenya and the U.S. signed the agreement, the country’s High Court on Dec. 11 suspended its implementation after two petitioners challenged its legality on grounds that it was negotiated in secrecy, lacks proper parliamentary approval, and violates Kenyans’ data privacy when their medical information is shared with America.

The agreement the U.S. and Uganda signed has not been challenged.

European Union

European Parliament resolution backs ‘full recognition of trans women as women’

Non-binding document outlines UN Commission on the Status of Women priorities

The European Parliament on Feb. 11 adopted a transgender-inclusive resolution ahead of next month’s U.N. Commission on the Status of Women meeting.

The resolution, which details the European Union’s priorities ahead of the meeting, specifically calls for “the full recognition of trans women as women.”

“Their inclusion is essential for the effectiveness of any gender-equality and anti-violence policies; call for recognition of and equal access for trans women to protection and support services,” reads the resolution that Erin in the Morning details.

The resolution, which is non-binding, passed by a 340-141 vote margin. Sixty-eight MPs abstained.

The commission will meet in New York from March 10-21.

A sweeping executive order that President Donald Trump signed shortly after he took office for a second time on Jan. 20, 2025, said the federal government’s “official policy” is “there are only two genders, male and female.” The Trump-Vance administration has withdrawn the U.S. from the U.N. LGBTI Core Group, a group of U.N. member states that have pledged to support LGBTQ and intersex rights, and dozens of other U.N. entities.