Movies

A rich ‘Color Purple’

New film a musical based on the Broadway show, not a Spielberg remake

Alice Walker’s 1982 Pulitzer-winning novel “The Color Purple” never needed a Steven Spielberg film adaptation to become a cultural touchstone – it had already achieved that before the director’s 1986 movie version made it to the screen – but it didn’t hurt, either.

Making stars of Whoopi Goldberg and Oprah Winfrey in the process, Spielberg’s film – his first foray into “serious” cinema – brought Walker’s epistolatory tale of early 20th-century Black life in Georgia to the attention of new audiences. Setting aside modern attitudes about Black narratives being interpreted by white storytellers, it was undeniably a “watershed moment,” when a seminal piece of Black literature – one that “spoke truth to power” while transcending notions of race, gender, and sexuality and asserting the rich cultural heritage of Black Americans – became part of mainstream consciousness.

That all happened nearly 40 years ago, but neither Walker’s book nor the multi-Oscar-nominated film it inspired have faded from public memory – and now, the latest evolution of the material that started it all has reached movie screens, just in time to become a must-see Christmas event for families across America. However, despite the impression one might get from watching the trailers, which largely evoke key moments from the Spielberg film, it’s not a remake.

Instead, “The Color Purple,” releasing on Christmas Day to join the fray for 2023’s “awards season” race, is a new iteration of Walker’s book, a stage-to-screen adaptation of the Tony-winning 2006 Broadway musical – originally crafted by playwright Marsha Norman with score and lyrics by Brenda Russell, Allee Willis, and Stephen Bray – penned by screenwriter Marcus Gardley. Again, the impression one might get from watching the film’s trailers, which downplay the movie’s identity as a musical to the point that many audiences will be surprised when its characters start singing, doesn’t exactly convey that information to anyone who isn’t already “in the know.”

Still, it’s not the movie’s fault if Warner Brothers, true to form for big-ticket Hollywood studios since at least the early 1970s, tried to hedge its bets in promoting the latest attempt at a blockbuster movie musical, and we can hardly blame them – the success rate for such films, in terms of both critical and audience acceptance, has been hit-or-miss for decades. No matter how much talk one may hear of the genre making a comeback, it’s never really happened. For every Oscar-winner like “Chicago,” there’s an embarrassing dud like “Dear Evan Hansen,” and that’s not even counting the inevitable controversies over the merits of original musicals like “La La Land,” which are typically derided by purist fans of the genre even as they garner acclaim from critics and industry insiders. But though it excises several songs from the stage original’s playlist (while adding a few new ones, a common ploy for Hollywood adaptations angling for an Original Song Oscar, with Siedah Garrett stepping in to replace the late Willis), the film is unapologetic about being a musical from its very first frames, rising above the politics of publicity to fully inhabit the artistic space in which it was intended to exist.

In the hands of director Blitz Bazawule (aka “Blitz the Ambassador”), a Ghanaian director (“The Burial of Kojo,” Beyonce’s “Black is King”) whose artistic monikers also include author, visual artist, rapper, singer-songwriter, and record producer, “The Color Purple” is a stylistic homage that pays tribute to the nostalgic glory of classic Hollywood while remaining firmly rooted in a contemporary aesthetic. To put it more plainly, the film’s many musical set-pieces borrow heavily from iconic Golden Age movies – think choreographed flights of fancy evoking seminal creators from Busby Berkeley to Gene Kelly to Bob Fosse – yet present them in a milieu more closely related to a modern music video. The eloquent choreography (by Fatima Robinson) exists outside the film’s period setting, incorporating movement rooted as much in modern dance as in the traditional styles that might seem (for some) more fitting to the material, and the music to which it is set often feels closer in spirit and execution to present-day R&B than the old-fashioned gospel-and-blues influences we might expect.

The result is both thrilling and jarring, an inspiring example of what can happen when a traditionally white mainstream genre is appropriated and reimagined by a rich and vibrant postmodern generation of blended ethnic ties possessing the boldness and skill to make it their own – which, in the heightened sensitivity of our divided age, might be a step too far for some viewers, but seems to us a more effective path than most toward breathing fresh life into the long-lamented musical genre, if such a thing were possible.

Yet between its many musical interludes, Bazawule’s film equally invests itself in the dramatic narrative, emulating a host of “realistic” cinematic influences beyond Spielberg’s contribution. This goes a long way toward getting us invested in the story and characters, especially given the beyond-expectation performances of the cast. Reprising the role she first played on Broadway, Fantasia Barrino creates a Miss Celie that puts the stress on under-appreciated intelligence rather than indoctrinated ignorance, giving us a different but no-less-compelling take on the character than Goldberg’s iconic turn, and Danielle Brooks (“Orange is the New Black”), also returning to her stage role, commands her every moment onscreen as the iron-willed Sofia. Taraji P. Henson, as free-spirited blues singer Shug Avery, captures the indomitable self-confidence and iron will that makes her a catalyst for more than one character’s change of heart, and Colman Domingo’s Mister succeeds at humanizing his toxicity sufficiently to clear a path for our empathy; in smaller but no-less-essential roles, Corey Hawkins and R&B singer H.E.R. (Gabriella Wilson) shine brightly enough to make their presence felt among the rest of the heavy-hitters, and up-and-comer Halle Bailey scores big as the long-separated sister that serves as a lifeline throughout Celie’s struggles.

All these stellar performances, coupled with Bazawule’s solid directorial vision and the non-ambiguous queerness with which it comports itself (the romance between Celie and Shug is allowed to blossom much more fully that we are shown in the Spielberg original), gives us ample reason to recommend “The Color Purple” – but we must also add a caveat that might be more a commentary on the stage musical than on the film derived from it.

Simply expressed, one can’t help but feel that there’s a disconnect between the sparse-but-richly-imagined prose that makes Walker’s book so compelling and the florid sentimentality of its translation into the musical format. The songs, while they might ring true as appropriate within the concept, never sufficiently illuminate what we are shown by the drama; they seem, at times, disconnected from everything else, a blatant appeal to our emotions rather than an integrated part of the whole. This is a particular problem for a film clearly rooted in the intertwined music and history of the Black culture it ostensibly tries to emulate.

Even so, such scholarly nitpicking is immaterial for most of our readers; while it may not deliver the most cohesive of musical conceits, it pulls off most of what it needs to, and for anybody who loves musicals as much as we do, that’s more than enough.

Movies

‘Housekeeping for Beginners’ embraces true meaning of family

Another triumph from young filmmaker Goran Stolevski

Once upon a time in America, queer people sometimes adopted their lovers as their “children” so that they could be legally bound together as family.

That’s not a revelation, though some queer younglings may be shocked to learn this particular nugget of hidden history, nor is it a call to political awareness in an election year when millions are actively working to roll back our freedoms. We bring it up merely as a sort of context for the world that provides the setting in “Housekeeping for Beginners,” the winner of the Queer Lion prize at 2023’s Venice Film Festival, which opened in limited U.S. theaters on April 5 and expanded for a wider release last weekend.

Written and directed by Goran Stolevski – a Macedonian-born Australian filmmaker whose two previous films, “You Won’t Be Alone” and “Of An Age,” both released in 2022, each met with critical acclaim – and submitted (unsuccessfully) as the official Oscar entry for International Feature from the Republic of North Macedonia, it’s a movie about what it means to be “family,” which touches on the political while placing its focus on the personal – in other words, on lived experience rather than ideological argument – and, in the process, drives home some very important existential warnings at a time when things could go either way.

Set in the North Macedonian capital of Skopje, it centers on social worker Dita (Anamaria Marinca), a middle-aged lesbian, whose house is a safe haven for a collection of outcasts. First and foremost is her girlfriend Suada (Alina Serban), a single mother of Romani heritage, but the “chosen family” in the household also includes Suada’s daughters, teenaged Vanesa (Mia Mustafi) and precocious 5-year-old Mia (Dżada Selim); Dita’s long-term friend Toni (Vladimir Tintor), a middle-aged gay man who works night shifts at a mental hospital; Toni’s new, much-younger boyfriend Ali (Samson Selim); and Elena (Sara Klimoska), an older and more worldly schoolmate of the other girls who serves as a makeshift big sister.

It is, unsurprisingly, a chaotic environment, a sea of revolving situations that largely goes on without Dita’s direct involvement, though she occasionally asserts more authority than she either has or cares to wield. That all changes, however, when Suada is diagnosed with aggressive pancreatic cancer, leading her to extract from her lover the promise that she will be mother to her children when she’s gone.

If you want a spoiler-free experience, you should stop reading now; further discussion of “Housekeeping for Beginners” requires us to reveal that Dita is forced to make good on that promise, even though she’s never had the desire to be a mother, and it’s not just a matter of making sure the kids get all their daily meals and show up for school on time. In North Macedonia, where same-sex relationships are not illegal but are neither granted the validation of lawful protections, the adoption of children requires a woman to have a husband, which means entering into a sham marriage with Toni – who is not quite a 100% onboard, himself – and listing him as the girls’ father. More difficult, perhaps, is gaining the trust of Suada’s two daughters, neither of whom is exactly receptive to the prospect of exchanging their real mother for a half-willing replacement. It’s this challenge that proves most daunting, triggering a crisis that will put every member of this cobbled-together family group to the test if they are to have any hope of hanging on to each other and making it work – something to which Dita finds herself growing deeply committed, despite her initial reticence about taking on the role of default matriarch.

Shot in Stolevski’s accustomed milieu – an intimate, cinema verité style built on handheld camerawork and near-exclusive reliance on close-up framing to capture the awkward blend of comfort and claustrophobia that often accompanies life in a crowded household environment – and leaving most of the expository cultural details, such as the impact of ethnic “caste” and the complicated hierarchy of layers involved in negotiating a peaceful coexistence with “normal” Macedonian society when your domestic and familial structures are anything but “normal”, to be gleaned by context rather than direct explanation. It works, of course; there’s something universally recognizable about the difficulty of “blending in” that helps us bridge the gap even if we don’t quite understand all the fine points as well as we might if we, like Stolevski, had grown up having to deal with them directly.

Even so, there are times when a bit of distance might be missed by audiences in need of a wider scope; it’s hard, after all, to get a palpable sense of space and location when most of what we see onscreen are the upper thirds of whichever cast members happen to be featured in each particular scene. But in case that sounds like a criticism, it’s important to point out that this is part of the film’s magic spell – because by making its physical environment essentially synonymous with its emotional one, Stolevski’s movie delivers its human truth without the unnecessary distraction of learning the ins and outs of a foreign cultural dynamic. The things we need to grasp, we do, without question, even if we don’t quite understand the full context, and what we walk away with in the end is a universally recognizable sense of family, carved in stark relief among a group of people who find it among themselves despite the lack of blood ties or common history to bind them to each other. That makes “Household for Beginners” an unequivocal triumph in one way, at least, because by driving home that hard-to-convey understanding, it manages to underscore the injustice and inhumanity of any world in which the validity of a family is subject to the judgment of cultural bias.

That’s not to say that “Housekeeping” is an unrelenting downer of political messaging. On the contrary, it is lifted by a clear imperative to show the joys of being part of such a family; the humor, the snark, the bright spots that arise even in the darkest moments – all these are amply and aptly portrayed, making sure that we never feel like we are being fed a doom-and-gloom scenario. Rather, we’re being reminded that it’s the visceral happiness that comes from being connected with those we love that matters far more than the rules and judgments of outsiders, which makes the hoops Dita and company have to jump through feel all the more absurd.

Though Stolevski, an Aussie citizen unspooling a narrative based in his country of origin, might not have intended it as such, the message of his film strikes a particular chord in 2024 America. The hardships of Dita and her brood as they try to simply stay together are a clear and pointed warning not to take for granted the hard-won freedoms that we have.

Add to that a superb collection of performances (BAFTA-winner Marinca and first-time actor Selim are standouts among the many), and you have another triumph from a young filmmaker whose reputation only gets more stellar with each effort.

Movies

After 25 years, a forgotten queer classic reemerges in 4K glory

Screwball rom-com ‘I Think I Do’ finds new appreciation

In 2024, with queer-themed entertainment available on demand via any number of streaming services, it’s sometimes easy to forget that such content was once very hard to find.

It wasn’t all that long ago, really. Even in the post-Stonewall ‘70s and ‘80s, movies or shows – especially those in the mainstream – that dared to feature queer characters, much less tell their stories, were branded from the outset as “controversial.” It has been a difficult, winding road to bring on-screen queer storytelling into the light of day – despite the outrage and protest from bigots that, depressingly, still continues to rear its ugly head against any effort to normalize queer existence in the wider culture.

There’s still a long way to go, of course, but it’s important to acknowledge how far we’ve come – and to recognize the efforts of those who have fought against the tide to pave the way. After all, progress doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and if not for the queer artists who have hustled to bring their projects to fruition over the years, we would still be getting queer-coded characters as comedy relief or tragic victims from an industry bent on protecting its bottom line by playing to the middle, instead of the (mostly) authentic queer-friendly narratives that grace our screens today.

The list of such queer storytellers includes names that have become familiar over the years, pioneers of the “Queer New Wave” of the ‘90s like Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, Gregg Araki, or Bruce LaBruce, whose work at various levels of the indie and “underground” queer cinema movement attracted enough attention – and, inevitably, notoriety – to make them known, at least by reputation, to most audiences within the community today.

But for every “Poison” or “The Living End” or “Hustler White,” there are dozens of other not-so-well-remembered queer films from the era; mostly screened at LGBTQ film festivals like LA’s Outfest or San Francisco’s Frameline, they might have experienced a flurry of interest and the occasional accolade, or even a brief commercial release on a handful of screens, before slipping away into fading memory. In the days before streaming, the options were limited for such titles; home video distribution was a costly proposition, especially when there was no guarantee of a built-in audience, so most of them disappeared into a kind of cinematic limbo – from which, thankfully, they are beginning to be rediscovered.

Consider, for instance, “I Think I Do,” the 1998 screwball romantic comedy by writer/director Brian Sloan that was screened last week – in a newly restored 4K print undertaken by Strand Releasing – in Brooklyn as the Closing Night Selection of NewFest’s “Queering the Canon” series. It’s a film that features the late trans actor and activist Alexis Arquette in a starring, pre-transition role, as well as now-mature gay heartthrob Tuc Watkins and out queer actor Guillermo Diaz in supporting turns, but for over two decades has been considered as little more than a footnote in the filmographies of these and the other performers in its ensemble cast. It deserves to be seen as much more than that, and thanks to a resurgence of interest in the queer cinema renaissance from younger film buffs in the community, it’s finally getting that chance.

Set among a circle of friends and classmates at Washington, D.C.’s George Washington University, it’s a comedic – yet heartfelt and nuanced – story of love left unrequited and unresolved between two roommates, openly gay Bob (Arquette) and seemingly straight Brendan (Christian Maelen), whose relationship in college comes to an ugly and humiliating end at a Valentine’s Day party before graduation. A few years later, the gang is reunited for the wedding of Carol (Luna Lauren Vélez) and Matt (Jamie Harrold), who have been a couple since the old days. Bob, now a TV writer engaged to a handsome soap opera star (Watkins), is the “maid” of honor, while old gal pals Beth (Maddie Corman) and Sarah (Marianne Hagan), show up to fill out the bridal party and pursue their own romantic interests. When another old friend, Eric (Diaz), shows up with Brendan unexpectedly in tow, it sparks a behind-the-scenes scenario for the events of the wedding, in which Bob is once again thrust into his old crush’s orbit and confronted with lingering feelings that might put his current romance into question – especially since the years between appear to have led Brendan to a new understanding about his own sexuality.

In many ways, it’s a film with the unmistakable stamp of its time and provenance, a low-budget affair shot at least partly under borderline “guerilla filmmaking” conditions and marked by a certain “collegiate” sensibility that results in more than a few instances of aggressively clever dialogue and a storytelling agenda that is perhaps a bit too heavily packed. Yet at the same time, these rough edges give it a raw, DIY quality that not only makes any perceived sloppiness forgivable, but provides a kind of “outsider” vibe that it wears like a badge of honor. Add to this a collection of likable performances – including Arquette, in a winning turn that gets us easily invested in the story, and Maelen, whose DeNiro-ish looks and barely concealed sensitivity make him swoon-worthy while cementing the palpable chemistry between them – and Sloan’s 25-year-old blend of classic Hollywood rom-com and raunchy ‘90s sex farce reveals itself to be a charming, wiser-than-expected piece of entertainment, with an admirable amount of compassion and empathy for even its most stereotypical characters – like Watkins’ soap star, a walking trope of vainglorious celebrity made more fully human than appearances would suggest by the actor’s honest, emotionally intelligent performance – that leaves no doubt its heart is in the right place.

Sloan, remarking about it today, confirms that his intention was always to make a movie that was more than just frothy fluff. “While the film seems like a glossy rom-com, I always intended an underlying message about the gay couple being seen as equals to the straight couple getting married,” he says. “ And the movie is also set in Washington to underline the point.”

He also feels a sense of gratitude for what he calls an “increased interest from millennials and Gen Z in these [classic queer indie] films, many of which they are surprised to hear about from that time, especially the comedies.” Indeed, it was a pair of clips from “his film”I Think I Do” featured on Queer Cinema Archive that “garnered a lot of interest from their followers,” and “helped to convince my distributor to bring the film back” after being unavailable for almost 10 years.

Mostly, however, he says “I feel very lucky that I got to make this film at that time and be a part of that movement, which signaled a sea change in the way LGBTQ characters were portrayed on screen.”

Now, thanks to Strand’s new 4K restoration, which will be available for VOD streaming on Amazon and Apple starting April 19, his film is about to be accessible to perhaps a larger audience than ever before.

Hopefully, it will open the door for the reappearance of other iconic-but-obscure classics of its era and help make it possible for a whole new generation to discover them.

Movies

Trans filmmaker queers comic book genre with ‘People’s Joker’

Alternative ‘Batman’ universe a medium for mythologized autobiography

It might come as a shock to some comic book fans, but the idea of super heroes and super villains has always been very queer. Think about it: the dramatic skin-tight costumes, the dual identities and secret lives, the inability to fit in or connect because you are distanced from the “normal” world by your powers – all the standard tropes that define this genre of pop culture myth-making are so rich with obviously queer-coded subtext that it seems ludicrous to think anyone could miss it.

This is not to claim that all superhero stories are really parables about being queer, but, if we’re being honest some of them feel more like it than others; an obvious example is “Batman,” whose domestic life with a teenage boy as his “ward” and close companion has been raising eyebrows since 1940. The campy 1960s TV series did nothing to distance the character from such associations – probably the opposite, in fact – and Warner Brothers’ popular ‘80s-’90s series of film adaptations solidified them even more by ending with gay filmmaker Joel Schumacher’s much-maligned “Batman and Robin,” starring George Clooney and Chris O’Donnell in costumes that highlighted their nipples, which is arguably still the queerest superhero movie ever made.

Or at least it was. That title might now have to be transferred to “The People’s Joker,” which – as it emphatically and repeatedly reminds us – is a parody in no way affiliated with DC’s iconic “Batman” franchise or any of its characters, even though writer, director and star Vera Drew begins it with a dedication to “Mom and Joel Schumacher.” Parody it may be, but that doesn’t keep it from also serving up lots of food for serious thought to chew on between the laughs.

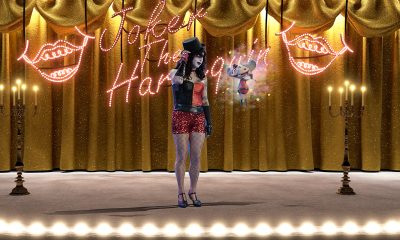

Set in a sort of comics-inspired dystopian meta-America where unsanctioned comedy is illegal, it’s the story of a young, closeted transgender comic (Drew) who leaves her small town home to travel to Gotham City and audition for “GCB” – the official government-produced sketch comedy show. Unfortunately, she’s not a very good comic, and after a rocky start she decides to leave to form a new comedy troupe (labeled “anti-comedy” to skirt legality issues) along with penguin-ish new friend Oswald Cobblepot (Nathan Faustyn). They collect an assortment of misfit would-be comedians to join them, and after branding herself as “Joker the Harlequin,” our protagonist starts to find her groove – but it will take negotiating a relationship with trans “bad boy” Mr. J (Kane Distler), a confrontation with her self-absorbed and transphobic mother (Lynn Downey), and making a choice between playing by the rules or breaking them before she can fully transition into the militant comic activist she was always meant to be.

Told as a wildly whimsical, mixed media narrative that combines live action with a quirky CGI production design and multiple styles of animation (with different animators for each sequence), “People’s Joker” is by no means the kind of big-budget blockbuster we expect from a movie about a superhero — or in this case, supervillain, though the topsy-turvy context of the story more or less reverses that distinction — but it should be obvious from the synopsis above that’s not what Drew was going for, anyway. Instead, the Emmy-nominated former editor uses her loopy vision of an alternative “Batman” universe as the medium for a kind of mythologized autobiography expressing her own real-life journey, both toward embracing her trans identity and forging a maverick career path in an industry that discourages nonconformity, while also spoofing the absurdities of modern culture. Subverting familiar tropes, yet skillfully weaving together multiple threads from the “real” DC Universe she’s appropriated with the detailed savvy of a die-hard fangirl, it’s an accomplishment likely to impress her fellow comic book fans — even if they can’t quite get behind the gender politics or her presentation of Batman himself (an animated version voiced by Phil Braun) as a closeted gay right-wing demagogue and serial sexual abuser.

These elements, of course, are meant to be deliberately provocative. Drew, like her screen alter ego, is a confrontation comic at heart, bent on shaking up the dominant paradigm at every opportunity. Yet although she takes aim at the expected targets – the patriarchy, toxic masculinity, corporate hypocrisy, etc. – she is equally adept at scoring hits against things like draconian ideals of political correctness and weaponized “cancel culture”, which are deployed with extreme prejudice from idealogues on both sides of the ideological divide. This means she might be risking the alienation of an audience which might otherwise be fully in her corner – but it also provides the ring of unbiased personal truth that keeps the movie from sliding into propaganda and elevates it, like “Barbie”, to the level of absurdist allegory.

Because ultimately, of course, the point of “People’s Joker” has little to do with the politics and social constructs it skewers along the way; at its core, it’s about the real human things that resonate with all of us, regardless of gender, sexuality, ideology, or even political parties: the need to feel loved, to feel supported, and most of all, to be fully actualized. That means the real heart of the film beats in the central thread of its troubled connection between mother and daughter, superbly rendered in both Drew and Downey’s performances, and it’s there that Joker is finally able to break free of her own self-imposed restrictions and simply “be” who she is.

Other performances deserve mention, too, such as Faustyn’s weirdly lovable “Penguin” stand-in and Outsider multi-hyphenate artist David Leibe Hart as Ra’s al Ghul – a seminal “Batman” villain here reimagined as a veteran comic that serves as a kind of Obi-Wan Kenobi figure in Joker’s quest. In the end, though, it’s Drew’s show from top to bottom, a showcase for not only her acting skills, which are enhanced by the obvious intelligence (including the emotional kind) she brings to the table, but her considerable talents as a writer, director, and editor.

For some viewers, admittedly, the low-budget vibe of this crowd-funded film might create an obstacle to appreciating the cleverness and artistic vision behind it, though Drew leans into the limitations to find remarkably creative ways to convey what she wants with the means she has at her disposal. Others, obviously, will have bigger problems with it than that. Indeed, the film, which debuted at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, was withdrawn from competition there and pulled from additional festival screenings after alleged corporate bullying (presumably from Warner Brothers, which owns the film rights to the Batman franchise) pressured Drew into holding it back. Clearly, concern over blowback from conservative fans – who would likely never see the film anyway – was enough to warrant strong arm techniques from nervous execs. Nevertheless, “The People’s Joker” made its first American appearance at LA’s Outfest in 2023, and is now receiving a rollout theatrical release that started on April 5 in New York, and continues this week in Los Angeles, with Washington DC and other cities to follow on April 12 and beyond.

If you’re in one of the places where it plays, we say it’s more than worth making the effort. If you’re not, never fear. A VOD/streaming release is sure to come soon.

-

State Department4 days ago

State Department4 days agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoCatching up with the asexuals and aromantics of D.C.

-

South America2 days ago

South America2 days agoArgentina government dismisses transgender public sector employees

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoSmithsonian staff concerned about future of LGBTQ programming amid GOP scrutiny