Movies

Intensive ‘Riefenstahl’ doc dives deep into a life of denial

German filmmaker spent decades trying to rehab her image

She was an exceptional woman of the early 20th century, an ambitious powerhouse with beauty, intelligence, and a bold creative vision, along with a determination for success that helped her become a pioneering female artist. She rose to prominence as a dancer, actress, photographer, and filmmaker who helped to define the aesthetic of an era, and reached the top of her profession in a male-controlled industry. Her career was relatively short, but her life was long enough to see her movies held up as cinema masterworks, studied by filmmakers and scholars for their blend of technical prowess and poetic vision, before eventually dying at the impressive age of 101 in 2003.

Yet today, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone eager to celebrate her legacy with anything more than carefully calculated appreciation.

That’s because her name was Leni Riefenstahl, and her filmmaking career ended prematurely not in retirement, nor from illness, nor even because of some scandalous gossip-column tale of adultery or sexual deviance. It ended because she built it in Germany, collaborating with Hitler and hob-nobbing with a who’s-who of infamous Nazis while enthusiastically creating spectacular documentaries that implicitly promoted a romanticized vision of the Third Reich. Her celebrated films were tarnished at the end of the war, their artistic merit eclipsed by the circumstances under which she had made them, and she spent much of the rest of her life as a relative pariah.

Indeed, as the cinema buffs out there probably already know, her name became practically synonymous with the idea of an artist whose work cannot be separated from their “problematic” ethical choices or political views; and while she would resurface when her films found muted-but-sincere appreciation from a new generation of critics, participating in interviews or appearing on the occasional talk show, she would spend the rest of her long life trying desperately to rehabilitate her image and her reputation in the public eye. Yet however often she repeated her claims – that she had never believed in the ideals of the Nazi movement, that she was never aware of the atrocities that took place under Hitler’s reign, that she had always only been motivated by “art” – most of the world seemed to never quite believe them.

Now, with an exceptionally comprehensive documentary from director Andres Veiel, Riefenstahl’s culpability in the Holocaust is up for examination again, and the timing couldn’t be any more perfect.

Granted unlimited access to Riefenstahl’s personal archives by her estate, Veiel draws deeply from the rich collection of imagery, writings, and artifacts contained there to assemble a measured and methodical portrait that is largely drawn from her own words and the pictographic record she chose to keep as part of her official legacy. Tracing her from her upbringing as the child of a stern authoritarian father and a mother who pushed her aggressively to succeed, it follows her rise in the German movie industry, where she gained fame as an actress before making her own first film as a director – “The Blue Light” (1932), a successful debut that caught the attention of Germany’s future führer, eventually leading to her first commission as a filmmaker for the Nazi government.

It goes on to examine the records of her associations with the Nazis during the wartime years, including an implied affair with Joseph Goebbels and an eventual marriage to a leading Wehrmacht officer, as well as a friendship with Nazi architect Albert Speers that would endure beyond his 20-year post-war prison sentence. Even more provocative, it explores her participation in the filming of location scenes for a propaganda film that used child inmates from a nearby concentration camp as extras – something that casts her claimed ignorance of the Nazi agenda in an even less convincing light.

It also utilizes the copious material that documents her lesser-known history after the war, during which she undertook the writing of her memoirs and returned – briefly – to the limelight with an extensive photographic study of the Nuba tribes of Sudan. But it’s her frustrated attempts to escape the stain of her past that provides the recurring theme for this portion of her life, punctuated by footage of her confrontations with interviewers, talk show hosts, and documentarians who asked her the questions she didn’t want to answer. In these moments, we can witness her unfiltered; we take note of her imperious manner and her quick temper, of the vanity which shows through her demands over lighting and makeup, and of the tongue-slips that inadvertently offer a glimpse at something we suspect she’d rather we didn’t see.

Veiel organizes all this information in a sort of kaleidoscopic narrative in which the various periods of his subject’s life bleed across and into each other, forming recognizable patterns which acknowledge and revel in her singular artistic vision, yet come to form an inescapably damning assessment of her long-held denials; though there’s no “smoking gun” that proves her unequivocally to be a liar, there are far too many of those “tongue-slips” to ignore. In the end, it leaves us with the inescapable conclusion that Leni Riefenstahl, whether she believed in the party agenda or not, was willing – at best – to overlook Hitler’s monstrous crimes against humanity for the sake of her own ambitions; even more, it suggests that the only thing she regretted afterward was the loss of her career and the stigma that was steeped upon her. In the end, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that she, like so many Germans of the Nazi era, wanted to simply pretend they didn’t know what was happening, when they were tacitly condoning it every step of the way.

With its leisurely pace and its brooding, minimalistic score by Freya Arde, “Riefenstahl” weaves a hypnotic effect that makes its two-hour runtime drift by like a dream, but there’s a meticulous logic and a rigorous empiricism to it all – marked by a sparseness of narration from its director, who merely supplies essential context to material he allows to speak for itself – that crystalizes the facts in way that’s entirely rational, and leaves us with an ominous feeling of familiarity with the world in which its controversial subject made her contribution to cinematic history; it’s this which renders Veiel’s documentary with such a profound sense of relevance, an ominous feeling of déjà vu that might be best illuminated through Riefenstahl’s own words from the final recorded conversation included in the film, in which she predicts that it will take “one or two generations” for Germany to reawaken to the “morality, decency, and virtue” to which its people are “predestined.”

Doing the math, her calculations feel chillingly accurate, though perhaps the spirit that has reawakened has more to do with a particular worldview than a specific national identity.

“Riefenstahl” premiered at the Venice film festival in 2024, with an American debut at Telluride earlier this year. Released in New York and screening at venues across the U.S. and Canada this fall, it’s a movie to watch for. Set your radar accordingly.

Movies

Radical reframing highlights the ‘Wuthering’ highs and lows of a classic

Emerald Fennell’s cinematic vision elicits strong reactions

If you’re a fan of “Wuthering Heights” — Emily Brontë’s oft-filmed 1847 novel about a doomed romance on the Yorkshire moors — it’s a given you’re going to have opinions about any new adaptation that comes along, but in the case of filmmaker Emerald Fennell’s new cinematic vision of this venerable classic, they’re probably going to be strong ones.

It’s nothing new, really. Brontë’s book has elicited controversy since its first publication, when it sparked outrage among Victorian readers over its tragic tale of thwarted lovers locked into an obsessive quest for revenge against each other, and has continued to shock generations of readers with its depictions of emotional cruelty and violent abuse, its dysfunctional relationships, and its grim portrait of a deeply-embedded class structure which perpetuates misery at every level of the social hierarchy.

It’s no wonder, then, that Fennell’s adaptation — a true “fangirl” appreciation project distinguished by the radical sensibilities which the third-time director brings to the mix — has become a flash point for social commentators whose main exposure to the tale has been flavored by decades of watered-down, romanticized “reinventions,” almost all of which omit large portions of the novel to selectively shape what’s left into a period tearjerker about star-crossed love, often distancing themselves from the raw emotional core of the story by adhering to generic tropes of “gothic romance” and rarely doing justice to the complexity of its characters — or, for that matter, its author’s deeper intentions.

Fennell’s version doesn’t exactly break that pattern; she, too, elides much of the novel’s sprawling plot to focus on the twisted entanglement between Catherine Earnshaw (Margot Robbie), daughter of the now-impoverished master of the titular estate (Martin Clunes), and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi), a lowborn child of unknown background origin that has been “adopted” by her father as a servant in the household. Both subjected to the whims of the elder Earnshaw’s violent temper, they form a bond of mutual support in childhood which evolves, as they come of age, into something more; yet regardless of her feelings for him, Cathy — whose future status and security are at risk — chooses to marry Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif), the financially secure new owner of a neighboring estate. Heathcliff, devastated by her betrayal, leaves for parts unknown, only to return a few years later with a mysteriously-obtained fortune. Imposing himself into Cathy’s comfortable-but-joyless matrimony, he rekindles their now-forbidden passion and they become entwined in a torrid affair — even as he openly courts Linton’s naive ward Isabella (Alison Oliver) and plots to destroy the entire household from within. One might almost say that these two are the poster couple for the phrase “it’s complicated.” and it’s probably needless to say things don’t go well for anybody involved.

While there is more than enough material in “Wuthering Heights” that might easily be labeled as “problematic” in our contemporary judgments — like the fact that it’s a love story between two childhood friends, essentially raised as siblings, which becomes codependent and poisons every other relationship in their lives — the controversy over Fennell’s version has coalesced less around the content than her casting choices. When the project was announced, she drew criticism over the decision to cast Robbie (who also produced the film) opposite the younger Elordi. In the end, the casting works — though the age gap might be mildly distracting for some, both actors deliver superb performances, and the chemistry they exude soon renders it irrelevant.

Another controversy, however, is less easily dispelled. Though we never learn his true ethnic background, Brontë’s original text describes Heathcliff as having the appearance of “a dark-skinned gipsy” with “black fire” in his eyes; the character has typically been played by distinctly “Anglo” men, and consequently, many modern observers have expressed disappointment (and in some cases, full-blown outrage) over Fennel’s choice to use Elordi instead of putting an actor of color for the part, especially given the contemporary filter which she clearly chose for her interpretation for the novel.

In fact, it’s that modernized perspective — a view of history informed by social criticism, economic politics, feminist insight, and a sexual candor that would have shocked the prim Victorian readers of Brontë’s novel — that turns Fennell’s visually striking adaptation into more than just a comfortably romanticized period costume drama. From her very opening scene — a public hanging in the village where the death throes of the dangling body elicit lurid glee from the eagerly-gathered crowd — she makes it oppressively clear that the 18th-century was not a pleasant time to live; the brutality of the era is a primal force in her vision of the story, from the harrowing abuse that forges its lovers’ codependent bond, to the rigidly maintained class structure that compels even those in the higher echelons — especially women — into a kind of slavery to the system, to the inequities that fuel disloyalty among the vulnerable simply to preserve their own tenuous place in the hierarchy. It’s a battle for survival, if not of the fittest then of the most ruthless.

At the same time, she applies a distinctly 21st-century attitude of “sex-positivity” to evoke the appeal of carnality, not just for its own sake but as a taste of freedom; she even uses it to reframe Heathcliff’s cruel torment of Isabella by implying a consensual dom/sub relationship between them, offering a fragment of agency to a character typically relegated to the role of victim. Most crucially, of course, it permits Fennell to openly depict the sexuality of Cathy and Heathcliff as an experience of transgressive joy — albeit a tormented one — made perhaps even more irresistible (for them and for us) by the sense of rebellion that comes along with it.

Finally, while this “Wuthering Heights” may not have been the one to finally allow Heathcliff’s ambiguous racial identity to come to the forefront, Fennell does employ some “color-blind” casting — Latif is mixed-race (white and Pakistani) and Hong Chau, understated but profound in the crucial role of Nelly, Cathy’s longtime “paid companion,” is of Vietnamese descent — to illuminate the added pressures of being an “other” in a world weighted in favor of sameness.

Does all this contemporary hindsight into the fabric of Brontë’s epic novel make for a quintessential “Wuthering Heights?” Even allowing that such a thing were possible, probably not. While it presents a stylishly crafted and thrillingly cinematic take on this complex classic, richly enhanced by a superb and adventurous cast, it’s not likely to satisfy anyone looking for a faithful rendition, nor does it reveal a new angle from which the “romance” at its center looks anything other than toxic — indeed, it almost fetishizes the dysfunction. Even without the thorny debate around Heathcliff’s racial identity, there’s plenty here to prompt purists and revisionists alike to find fault with Fennell’s approach.

Yet for those looking for a new window into to this perennial classic, and who are comfortable with the radical flourish for which Fennell is already known, it’s an engrossing and intellectually stimulating exploration of this iconic story in a way that exchanges comfortable familiarity for unpredictable chaos — and for cinema fans, that’s more than enough reason to give “Wuthering Heights” a chance.

Movies

As Oscars approach, it’s time to embrace ‘KPop Demon Hunters’

If you’ve resisted it, now’s the time to give in

If you’re one of the 500 million people who made “KPop Demon Hunters” into the most-watched original Netflix title in the streaming platform’s history, this article isn’t for you.

If, however, you’re one of the millions who skipped the party when the Maggie Kang-created animated musical fantasy debuted last summer, you might be wondering why this particular piece of pop youth culture is riding high in an awards season that seems all but certain to end with it winning an Oscar or two; and if that’s the case, by all means, keep reading.

We get it. If you’re not a young teen (or you don’t have one), it might have escaped your radar. If you don’t like KPop, or the fantasy genre just isn’t your thing, there would be no reason for that title to pique your interest – on the contrary, you would assume it’s just a movie that wasn’t made for you and leave it at that.

It’s now more than half a year later, though, and “KPop Demon Hunters” has yet to fade into pop culture memory, in spite of the “new, now, next” pace with which our social media world keeps scrolling by. It might feel like there’s been a resurgence of interest since the film’s ongoing sweep of major awards in the Best Animated Film and Best Song categories has led it close to Oscar gold, but in reality, the interest never really flagged. Millions of fans were still streaming the soundtrack album on a loop, all along.

It wasn’t just the music that they embraced, though that was definitely a big factor – after all, the film’s signature song, “Golden,” has now landed a Grammy to display alongside all of its film industry accolades. But Kang’s anime-influenced urban fantasy taps into something more substantial than the catchiness of its songs; through the filter of her experience as a South Korean immigrant growing up in Canada, she draws on the traditions and mythology of her native culture while blending them seamlessly into an infectiously contemporary and decidedly Western-flavored “girl power” adventure about an internationally popular KPop girl band – Huntrix, made up of lead singer Rumi (Arden Cho), lead dancer Mira (May Hong), and rapper/lyricist Zoey (Ji-young Yoo) – who also happen to be warriors, charged with protecting humankind from the influence of Gwi-Ma (Lee Byung-hun), king of the demon world, which is kept from infiltrating our own by the power of their music and their voices. Oh, and also by their ability to kick demon ass.

In an effort to defeat the girls at their own game, Gwi-Ma sends a demonic boy band led by handsome human-turned-demon Jinu (Ahn Hyo-seop) to steal their fans, creating a rivalry that (naturally) becomes complicated by the spark that ignites between Rumi and Jinu, and that forces Rumi to confront the half-demon heritage she has managed to keep secret – even from her bandmates – but now threatens to destroy Huntrix from within, just when their powers are needed most.

It’s a bubble-gum flavored fever-dream of an experience, for the most part, which never takes itself too seriously. Loaded with outrageous kid-friendly humor and pop culture parody, it might almost feel as if it were making fun of itself if not for the obvious sincerity it brings to its celebration of all things K-Pop, and the tangible weight it brings along for the ride through its central conflict – which is ultimately not between the human and demon worlds but between the long-held prejudices of the past and the promise of a future without them.

That’s the hook that has given “KPop Demon Hunters” such a wide-ranging and diverse collection of fans, and that makes it feel like a well-timed message to the real world of the here and now. In her struggle to come to terms with her part-demon nature – or rather, the shame and stigma she feels because of it – Rumi becomes a point of connection for any viewer who has known what it’s like to hide their full selves or risk judgment (or worse) from a world that has been taught to hate them for their differences, and maybe what it’s like to be taught to hate themselves for their differences, too.

For obvious reasons, that focus adds a strong layer of personal relevance for queer audiences; indeed, Kane has said she wanted the film to mirror a “coming out” story, drawing on parallels not just with the LGBTQ community, but with people marginalized through race, gender, trauma, neurodivergence – anything that can lead people to feel like an “other” through cultural prejudices and force them to deal with the pressure of hiding an essential part of their identity in order to blend in with the “normal” community. It plays like a direct message to all who have felt “demonized” for something that’s part of their nature, something over which they have no choice and no control, and it positions that deeply personal struggle as the key to saving the world.

Of course, “KPop Demon Hunters” doesn’t lean so hard into its pro-diversity messaging that it skimps on the action, fun, and fantasy that is always going to be the real reason for experiencing a genre film where action, fun, and fantasy are the whole point in the first place. You don’t have to feel like an “other” to enjoy the ride, or even to get the message – indeed, while it’s nice to feel “seen,” it’s arguably much more satisfying to know that the rest of the world might be learning how to “see” you, too. By the time it reaches its fittingly epic finale, Kane’s movie (which she co-directed with Chris Appelhans, and co-wrote with Appelhans, Danya Jimenez, and Hannah McMechan) has firmly made its point that, in a community threatened by hatred over perceived differences, the real enemy is our hate – NOT our differences.

Sure, there are plenty of other reasons to enjoy it. Visually, it’s an imaginative treat, building an immersive world that overlays an ancient mythic cosmology onto a recognizably contemporary setting to create a kind of whimsical “metaverse” that feels almost more real than reality (the hallmark of great mythmaking, really); yet it still allows for “Looney Toons” style cartoon slapstick, intricately choreographed dance and battle sequences that defy the laws of physics, slick satirical commentary on the juggernaut of pop music and the publicity machine that drives it, not to mention plenty of glittery K-Pop earworms that will take you back to the thrill of being a hormonal 13-year-old on a sugar high; but what makes it stand out above so many similar generic offerings is its unapologetic celebration of the idea that our strength is in our differences, and its open invitation to shed the shame and bring your differences into the light.

So, yes, you might think “KPop Demon Hunters” would be a movie that’s exactly what it sounds like it will be – and you’d be right – but it’s also much, much more. If you’ve resisted it, now’s the time to give in.

At the very least, it will give you something else to root for on Oscar night.

Movies

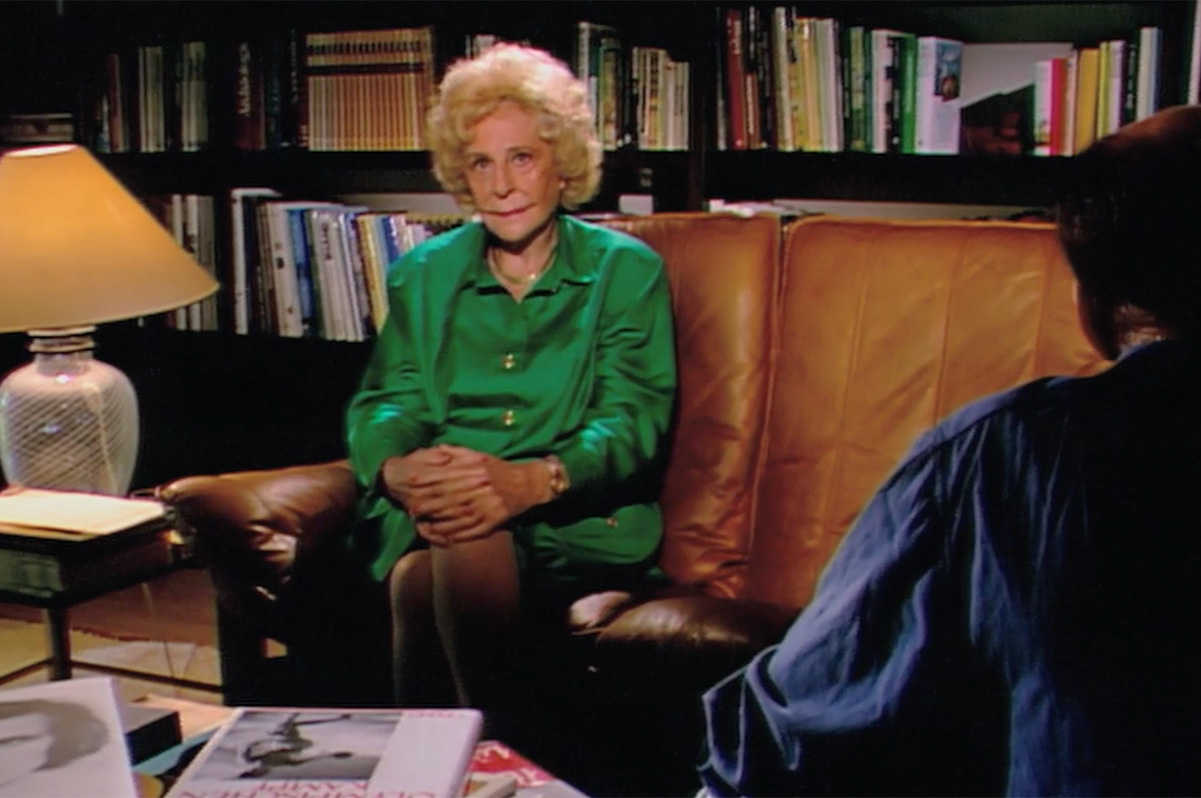

50 years later, it’s still worth a return trip to ‘Grey Gardens’

Documentary remains entertaining despite its darkness

If we were forced to declare why “Grey Gardens” became a cult classic among gay men, it would be all the juicy quotes that have become part of the queer lexicon.

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of its theatrical release this month, the landmark documentary profiles two eccentrics: Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale and her daughter, Edith Bouvier Beale (known as “Big” and “Little” Edie, respectively), the aunt and cousin of former first lady Jaqueline Kennedy Onassis and socialite Lee Radziwell. Once moving within an elite circle of American aristocrats, they had fallen into poverty and were living in isolation at their run-down estate (the Grey Gardens of the title) in East Hampton, Long Island; they re-entered the public eye in 1972 after local authorities threatened eviction and demolition of their mansion over health code violations, prompting their famous relatives to swoop in and pay for the necessary repairs to avoid further family scandal.

At the time, Radziwell had enlisted filmmaking brothers David and Albert Maysles to take footage for a later-abandoned project of her own, bringing them along when she went to put in an appearance at the Grey Gardens clean-up efforts. It was their first encounter with the Beales; the second came two years later, when they returned with their cameras (but without Radziwell) and proceeded to make documentary history, turning the two Edies into unlikely cultural icons in the process.

On paper, it reads like something painful: two embittered former socialites, a mother and daughter living among a legion of cats and raccoons in the literal ruins of their former life, where they dwell on old memories, rehash old conflicts, and take out their resentments on each other, attempting to keep up appearances while surviving on a diet that may or may not include cat food. Truthfully, it is sometimes difficult to watch, which is why it’s easier to approach from surface level, focusing on the “wacky” eccentricities and seeing the Beales as objects for ridicule.

Yet to do so is to miss the true brilliance of a movie that is irresistible, unforgettable, and fascinating to the point of being hypnotic, and that’s because of the Beales themselves, who are far too richly human to be dismissed on the basis of conventional judgments.

First is Little Edie, in her endless array of headscarves (to cover her hair loss from alopecia) and her ever-changing wardrobe of DIY “revolutionary costumes,” a one-time model and might-have-been showgirl who is obviously thrilled at having an audience and rises giddily to the occasion like a pro. Flamboyant, candid, and smarter than we think, she’s also fearlessly vulnerable; she gives us access to an emotional landscape shaped by the heartbreaks of a past that’s gradually revealed as the movie goes on, and it’s her ability to pull herself together and come back fighting that wins us over. By the time she launches into her monologue about being a “S-T-A-U-N-C-H” woman, we have no doubt that it’s true.

Then there’s Big Edie, who comes across as an odd mix of imperious dowager and down-to-earth grandma. She gets her own chance to shine for the camera, especially in the scenes where she reminisces about her early days as a “successful” amateur vocalist, singing along to records of songs she used to perform as glimpses emerge of the beauty and talent she commanded in her prime. She’s more than capable of taking on her daughter in their endless squabbles, and savvy enough to score serious points in the conflict, like stirring up jealousy with her attentions to beefy young handyman Jerry – whom the younger Edie has dubbed “the Marble Faun” – when he comes around to share a feast of boiled corn-on-the-cob with them. “Jerry likes the way I do my corn,” she deadpans to the camera, even though we know it’s meant for Little Edie.

It’s not just that their eccentricities verge on camp; that’s certainly an undeniable part of the appeal, but it falls away quickly as you begin to recognize that even if these women are putting on a show for the camera, they’re still being completely themselves – and they are spectacular.

Yes, their verbal sparring is often shrill and palpably toxic – in particular, Big Edie has no qualms about belittling and shaming her daughter in an obviously calculated effort to undermine her self-esteem and discourage her from making good on her repeated threats to leave Grey Gardens. We know she is acting from fear of abandonment, but it’s cruel, all the same.

These are the moments that disturb us more than any of the dereliction we see in their physical existence; fed by nostalgia and forged in a deep codependence that neither wants to acknowledge, their dynamic reflects years of social isolation that has made them into living ghosts, going through the habitual motions of a long-lost life, ruminating on ancient resentments, and mulling endlessly over memories of the things that led them to their outcast state. As Little Edie says early on, “It’s very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present. Do you know what I mean?”

That pithy observation, spoken conspiratorially to the Maysles’ camera, sets the tone for the entirety of “Grey Gardens,” perhaps even suggesting an appropriate point of meditation through which to contemplate everything that follows. It’s a prime example of the quotability that has helped this odd little movie endure as a fixture in queer culture; for many LGBTQ people, both Edies – born headstrong, ambitious, and independent into a social strata that only wanted its women to be well-behaved – became touchstones of frustrated longing, of living out one’s own fabulousness in isolated secrecy. Add to that shared inner experience Little Edie’s knack for turning scraps into kitschy fashion (and the goofy-but-joyous flag dance she performs as a sort of climactic topper near the end), and it should be obvious why the Maysles Brothers’ little project still resonates with the community five decades later.

Indeed, watching it in today’s cultural climate, it strikes chords that resonate through an even wider spectrum, touching on feminist themes through these two “problematic” women who have been effectively banished for refusing to fit into a mold, and on the larger issue of social and economic inequality that keeps them trapped, ultimately turning them against each other in their powerlessness.

With that in mind, it’s clear these women were never filmed to be objects of ridicule. They’re survivors in a world in which even their unimaginably wealthy relatives would rather look away, offering a bare minimum of help only when their plight becomes a matter of public family embarrassment, and the resilience they show in the face of tremendous adversity makes them worthy of celebration, instead.

That’s why “Grey Gardens” still hits close to home, why it entertains despite its darkness, and why we remember it as something bittersweet but beautiful. By the end of it, we recognize that the two Edies could be any of us, which means they are ALL of us – and if they can face their challenges with that much “revolutionary” spirit, then maybe we can be “staunch” against our adversities, too.