a&e features

Pride, activist groups, the gay press and more take form in wake of Stonewall riots

Bumps and hurdles loomed in most areas as movement came of age in ‘70s and beyond

The most impactful legacy of Stonewall isn’t what happened those few nights, but what grew out of it — annual Pride celebrations, of course, but also the gay press, a proliferation of rights groups, de-classification of homosexuality as mental illness, disco, sexual lib, AIDS and more. Whole books have been written on each of these topics, for anyone interested in further study.

THE BIRTH OF PRIDE

Some of the people who rioted starting on June 28, 1969, once things settled, started to organize and a group called the Stonewall Veterans Association, which is still in existence, formed.

In November 1969, Craig Rodwell (1940-1993), owner of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop (the country’s first gay bookstore), along with his partner Fred Sargeant, Ellen Broidy and Linda Rhodes, proposed a New York City march to commemorate the riots. He introduced a resolution at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organization (ERCHO) in Philadelphia.

“We propose that a demonstration be held annually on the last Saturday in June in New York City to commemorate the 1969 spontaneous demonstrations on Christopher Street and this demonstration be called Christopher Street Liberation Day,” the resolution said. “No dress or age regulations shall be made for this demonstration.”

The concept of Pride being held in other cities simultaneously was ingrained in the concept from the outset.

“We also propose that we contact homophile organizations throughout the country and suggest that they hold parallel demonstrations on that day. We propose a nationwide show of support,” the resolution stated.

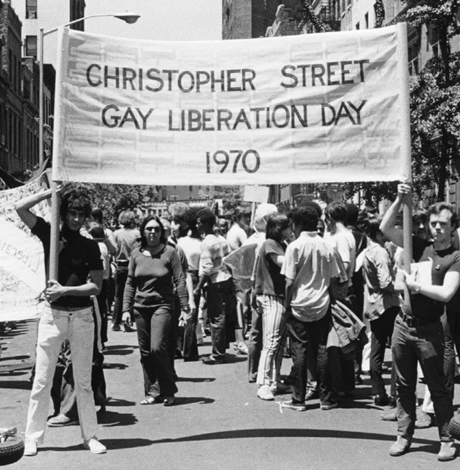

Christopher Street Liberation Day was held June 28, 1970, the first gay Pride march in the U.S. It covered 51 blocks to Central Park with a parade permit reluctantly delivered just two hours before the scheduled start time. Marches were simultaneously held in Los Angeles and Chicago. In 1971, it had spread to Boston, Dallas, Milwaukee and three European cities as well. Pride in Washington started in 1975.

Since 1984, the parade and related events in New York have been produced and organized by Heritage of Pride, a volunteer, non-partisan LGBT group.

THE GAY PRESS

The gay press didn’t begin with Stonewall. The earliest known publication had an inauspicious start. In 1947, an underworked secretary trying to look busy, typed, stapled and distributed 12 copies of Vice Versa, which she dubbed “America’s gayest magazine.” Since then, thousands have followed in her steps producing about 2,600 — at their height — publications ranging from weekly newspapers to more radical tabloids to glossy monthly magazines.

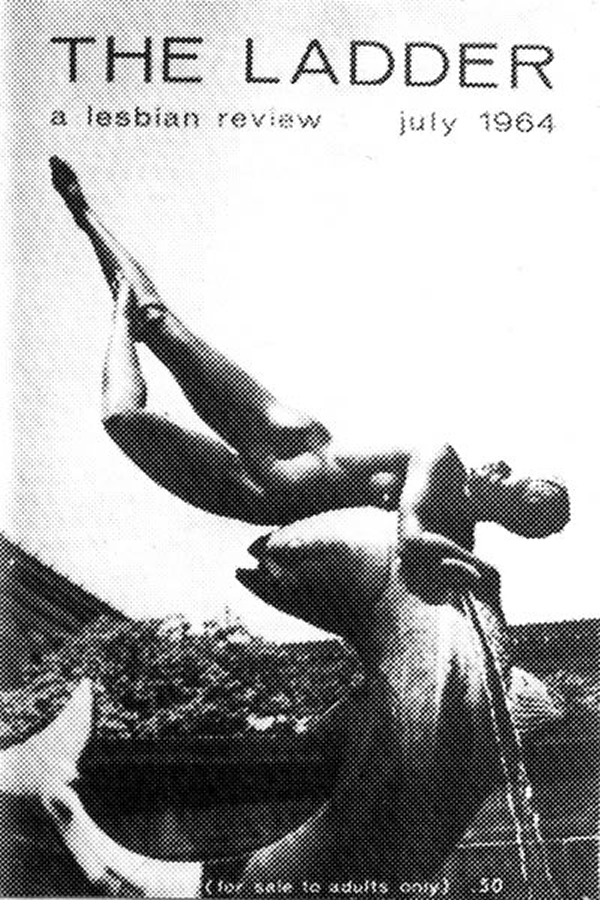

Seminal pre-Stonewall publications included Ladder, Vector and the Los Angeles Advocate.

The number of these publications exploded after Stonewall. It was seen as necessary as even the most liberal alternative press of the day — in New York, The Village Voice, refused to print the word gay. “Throughout the ‘70s, people who depended solely on mainstream media for news would hardly have been aware of the gay rights movement,” writes author/historian Eric Marcus in his 2002 book “Making Gay History.” “With a few notable exceptions, the television networks, daily newspapers and newsmagazines gave little coverage to gay issues.”

“After the apocalyptic Stonewall impulse, the press erupted in so many directions that it is impossible to document when each publication was founded, how long it existed or who edited it,” writes Rodger Streitmatter, author of “Unspeakable: the Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America.”

“Our Own Voices: A Directory of Lesbian and Gay Periodicals” listed 150 publications by 1972, Streitmatter writes.

One of the most influential was called simply GAY, started in December 1969 by gay press veterans (and partners) Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke, who’d covered Stonewall. It soon became, according to Streitmatter, the “newspaper of record for gay America.”

Veteran activist Lilli Vincenz, who wrote a lesbian column for GAY, is quoted in “Unspeakable” as having said, “It was the newspaper of the day. If you were gay and you wanted to find out what was going on in the world, you turned to GAY.”

It sold 20,000 copies of its first issue (at 40 cents per copy) and reached a monthly circulation of 25,000 by its second issue, figures that took the Advocate two years to build. Within six weeks, two other New York-based newspapers were launched — Come Out! and Gay Power. GAY continued until Clarke was murdered in 1975.

Streitmatter writes later in the book that the publications “that survived the aftershocks of Stonewall were those with a combination of calm voices and stable finances,” citing GAY in New York and The Advocate in Los Angeles as leaders.

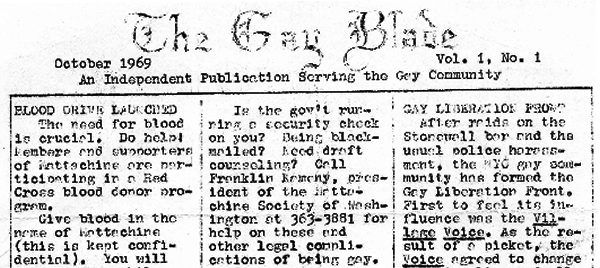

But two months before GAY was launched, in October 1969, Vincenz and a small group of men and women met in the basement of a Connecticut Avenue building to work on the first issue of the Gay Blade. The monthly, mimeographed one-sheet issued by a volunteer staff contained three columns of news, community notices and a small advertisement for someone who wanted to sell a car, writes author Edward Alwood in his 1996 book “Straight News: Gays, Lesbians and the News Media.”

“By distributing copies at the city’s gay and lesbian bars, they quickly established the Blade as a source of valuable information that was not available from any other source,” Alwood writes.

Editor Nancy Tucker told Alwood they printed “things that we thought were important to the mental health and social welfare of other people like us,” Alwood quotes her as having said. “Periodically we ran warnings of blackmailers who hung around Dupont Circle or the gay bars. We wrote about rough cops. There were plenty of military and government workers who were undergoing some type of security investigation and all of those people needed to know about their rights. These were a heavy orientation for us.”

It was the first of a new generation of gay papers that included Gay Community News in Boston, NewsWest in Los Angeles, Gay News in Pittsburgh and GayLife in Chicago, Alwood writes.

“Unlike the early homophile press, which stressed identity and cooperation, this second generation concentrated almost solely on political change and resistance,” Alwood writes.

The Gay Blade was rechristened the Washington Blade in 1980 and went to weekly publication in 1983. It’s the oldest continually operating LGBT newspaper in the country. It celebrates its 50th anniversary in October.

REGIONAL GAY RIGHTS GROUPS

Although groups like the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis had been around since the ‘50s, things became more emboldened after Stonewall. The Gay Liberation Front was the first organization to use gay in its name. Previously, all “homophile” (as they were known) groups purposefully did not.

Legendary early activists Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen were vacationing on Fire Island when they heard about Stonewall. Upon returning to the city in September, they began attending meetings of the Gay Liberation Front and encountered a much different group of people and ethos.

“They were huge meetings, it was the best theater in town,” Lahusen is quoted as having said in “Making Gay History.” “This was the heyday of radical chic … and here I was this plain Jane dinosaur from the old gay movement.”

Gittings said there was zero acknowledgement of the pre-Stonewall efforts.

“Suddenly here were all these people with absolutely no track record in the movement who were telling us, in effect, not only what we should do but what we should think,” she’s quoted as having said in “Making Gay History.” “The arrogance of it was really what upset me.”

Gittings said she and Frank Kameny were even asked at one Philadelphia meeting who they were and what they were doing there.

“For once, I think even Frank was dumbfounded,” Gittings is quoted as having said. “As if we owed them an explanation.”

Gittings said right after Stonewall, the Gay Liberation Front and the Mattachine Society, which some perceived as having been slow to respond to the riots, were the only two active groups.

“Mattacine was so stuffy and its day was over,” Lahusen said in “Making Gay History.” “These organizations seem to have a built-in life expectancy.”

“Mattachine wasn’t up to managing the lively response to the Stonewall riots and GLF came in to fill the void,” Gittings told author Marcus.

The Gay Liberation Front (a name used by multiple groups over the years), however, disbanded after just four months when members were unable to agree on operating procedure. In December 1969, some people who had attended Front meetings but left frustrated formed Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), an “orderly” group to be focused entirely on gay issues. A D.C. chapter had formed by 1971. It became the Gay & Lesbian Activist Alliance in the ‘80s, and continues to this day.

Many of the main groups with major name recognition today started later. The National Gay Task Force (now the National LGBTQ Task Force) started in 1973. Two groups merged to form the largest, Human Rights Campaign, in the early ‘80s.

Many of the state groups came much later, uniting around the marriage issue. The California Alliance for Pride and Equality was founded in 1999 and only became Equality California in 2003. The now-dissolved Empire State Pride Agenda was founded in 1990 through a merger of two earlier groups. By 2005, it was the largest state lobbying group.

AIDS

In a roundabout way, Stonewall, in time, also brought attention to the disparate health care needs of LGBT people. That’s the contention of Perry N. Halkitis, dean of Rutgers School of Public Health and author of the new book “Out in Time: From Stonewall to Queer; How Gay Men Came of Age Across the Generations.”

“The riots allowed gay people to say ‘we exist’ and create a demand for health equity,” Halkitis said in a recent interview with tapinto.net. “The civil disobedience of Stonewall served as a catalyst to the activism of the AIDS era, which in turn has contributed to the foundations of how public health today emphasizes social justice and health equity.”

Although initially about wholly separate issues, Stonewall started a movement that was eventually “catapulted” 13 years later when HIV hit, he says.

“As the riots framed the basis for the recognition of gay people as viable members of the population, the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ’90s created the circumstances by which they would come to demand that the government and society attend to their well-being,” Halkitis said in the tapinto.net interview. “Before then, gay people kept silent and were invisible to their doctors, who were unaware they were gay or did not understand the mental health and drug issues they were facing. The AIDS crisis shined a light on the fact that there was this population that needed specific health services beyond what was given to the general population.”

Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, deputy commissioner for the Division of Disease Control of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said in a New York Times interview last week that the histories of Stonewall and AIDS are inextricably linked and have affected what’s still happening today.

“It’s so critical that you had an uprising, and it became not just folks being downtrodden by their system but actually then fighting back,” Daskalakis told the Times. “I feel that the fighting spirit now is like the ACT UP experience in New York. There was a feeling that it was part of LGBTQ rights to ask for faster, better support and funding to fight HIV. … I think the legacy of activism remains powerful decades later.”

As the number of deaths soared, gay and lesbian people and gay rights organizations redirected their energies, Marcus writes in “Making Gay History.”

“Many thousands of gay people who had never participated in gay rights efforts were motivated to join the fight against AIDS,” he writes. “New organizations joined existing ones to provide care for the sick and dying, conduct AIDS education programs, lobby local and federal governments for increased funding for AIDS research, pressure medical researchers and drug companies to become more aggressive in their search for treatments and a cure and fight discrimination against people with AIDS and those infected with HIV.”

AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION

In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association removed the diagnosis of “homosexuality” from the second edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.

In the mid-20th century, some homophile activist groups accepted psychiatry’s illness model as an alternative to societal condemnation of homosexuality’s supposed “immorality” and were willing to work with professionals who sought to “treat” or “cure” them, Jack Drescher writes in his 2015 study “Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality.” Other activists, however, forcefully rejected the pathological model as a major contributor to the stigma and in the wake of the Stonewall riots, brought modern sex research theories to the attention of the APA.

Believing psychiatric theories to be a major contributor to anti-gay social stigma, activists disrupted the 1970 and 1971 annual APA meetings.

Although, Drescher writes, there were rumblings happening within the world of psychiatry that helped the gay cause, “the most significant catalyst for diagnostic change was gay activism.”

Kameny and Gittings spoke on a 1971 APA panel entitled “Gay is Good.” They returned in ’72, joined by Dr. John Fryer, who appeared anonymously as a “homosexual psychiatrist.”

APA’s Nomenclature Committee eventually recommended removing homosexuality when it determined it unique among the supposed mental disorders in that in and of itself, it did not cause distress nor was it associated with generalized impairment in social effectiveness of functioning.

It wasn’t a completely cut-and-dried affair; the psychiatric world continued grappling with the controversial decision for years, Drescher writes in his scholarly article, but it was “the beginning of the end of organized medicine’s official participation in the social stigmatization of homosexuality.”

Many people, both inside and outside the psychology profession, claimed the APA had succumbed to pressure from gay activists and while it was true that many gay men and lesbians had exerted pressure, there were also respected psychiatrists within the organization who worked to affect the change, Marcus writes in “Making Gay History.” One was Dr. Judd Marmor, a Los Angeles psychiatrist.

“We didn’t merely remove homosexuals from the category of illness. We stated that there was no reason why a priori a gay man or woman could not be just as healthy, just as effective, just as law abiding and just as capable of functioning as any heterosexual,” Marmor is quoted as having said in Marcus’s book. “Furthermore, we asserted that laws that discriminated against them in housing or in employment were unjustified. So it was a total statement.”

Shortly thereafter, the American Psychological Association and the American Bar Association came out in support of gays.

“It was an important step that we took,” Marmor said in “Making Gay History.”

DISCO

Disco music, a type of dance music and the subculture around it that emerged in the ‘70s from the U.S. urban nightlife scene, is inextricably linked to post-Stonewall gay life.

Its “four-on-the-floor” beats, syncopated basslines and shimmery instrumentation flourished in venues popular with black, Latinx and gay nightlife lovers mostly in major cities on the East Coast at the dawn of the ‘70s. The most popular disco artists were Donna Summer, Gloria Gaynor, the Bee Gees, Chic, KC and the Sunshine Band, the Village People, Thelma Houston and others. Pop acts like Diana Ross and Michael Jackson, who’d had hits in other genres, jumped on the disco bandwagon with success.

In his essay “In Defense of Disco,” gay writer Richard Dyer writes that disco gave gay men a mainstream musical genre they could embrace.

“All my life, I’ve liked the wrong music,” he writes. “I never liked Elvis and rock ’n roll; I always preferred Rosemary Clooney. And since I became a socialist, I’ve often felt virtually terrorized by the prestige of rock and folk on the left. … Disco is more than just a form of music, although certainly music is at the heart of it. Disco is also kinds of dancing, club, fashion, film — in a word, a certain sensibility.”

Thematically, Dyer (whose essay is included in the 1995 anthology “Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian and Queer Essays on Popular Culture”), writes that disco has both rhythmic and lyrical appeal to gay men.

“No wonder (Diana) Ross is (was?) so important in gay male scene culture for she both reflects what that culture takes to be an inevitable reality — that relationships don’t last — and at the same time celebrates it, validates it.”

“Our music owes so much to the gay clubs that first nurtured it, which in turn helped to create safe spaces that allowed a marginalized population the freedom to be themselves,” writes Ned Shepard in a 2016 Cuepoint essay.

He cites a comment from Barry Walters from Billboard.

“The history of dance music in America and the history of LGBT folks — particularly those of color — coming together to create a cultural utopia was and still is inseparable. Neither would have happened without the other,” Walters is quoted as having said.

SEXUAL LIBERATION

Sexual liberation in the pre-AIDS era for lesbian and gay activists was a heated topic. Gay men especially enjoyed dabbling liberally without any of the baggage sexually adventurous women — despite this being the era of Helen Gurley Brown and her landmark 1962 book “Sex and the Single Girl” — faced, but the concern that gay rights would be overly associated with a free sex narrative was contentious and variations of that argument continue to this day.

The 1980 William Friedkin (“The Exorcist”)-directed movie “Cruising” was a nadir of the conundrum.

“There was … a political and ideological split in the gay community about whether or not it was valuable or necessary to show the leather and sadomasochism aspect of the community on screen,” recalls “The Celluloid Closet” author Vito Russo in “Making Gay History.” “There were middle-of-the-road gays who found this kind of thing horrifying. Just because you’re gay doesn’t mean you were necessarily acquainted with the more far-out aspects of gay sexuality, especially in the 1970s. There were a lot of gay men, and certainly lesbians, in this country who would have been deeply shocked by the sex bars in New York. … Suddenly the issue became, ‘Do we want to present this to the world as the way gay people are?’ The public was not going to distinguish between one group of gay people and another.”

Nancy Walker (not the “Rhoda” actress) writes of her volunteer work in the early ‘70s at the Boston-based weekly Gay Community News in “Making Gay History.”

“We wanted gay liberation but what did that mean,” she writes. “Did it mean equal rights? To me, that’s all I ever wanted. On the other hand, some of them wanted to be able to fuck in the parks. Well, that’s wonderful, but if they did, I wouldn’t take my children there either. How far is sexual freedom supposed to go? Are you allowed to have intercourse on the street corner because you feel like doing it? How does that make you different from a dog? What happens to civilization when people lose all their socialization and have sex, where and with whom they please? We have to have a little bit of self control, a little discipline. I’m sorry, but I’m not interested in sexual freedom. I’m interested in being able to live.”

Ultimately things somewhat self calibrated — AIDS brought a day of reckoning writ large, it didn’t manage to kill off gay bathhouse culture and, of course, antiretroviral meds and PrEP were game changers in the AIDS war. But it’s not all gay “Pollyanna.” Entrapment of cruising gay men remains a problem. As recently as 2015 in Rehoboth Beach, Del., of all places, 12 men were arrested for public lewdness by undercover police officers.

a&e features

Transmission DC breathes new life into a storied sound space

A fresh home for boundary-pushing culture on H Street

Late last year, phoenix-style, a fresh home for boundary-pushing culture arose on the H Street corridor. Transmission DC – a queer, trans, and POC-owned, operated, and centered community-focused venue – powered on in the former home to the Rock & Roll Hotel (famously, not a hotel, but very much rock & roll). Transmission (1353 H St., N.E.) arrives secure in its mandate – or even birthright – to provide a place to celebrate creativity and music through a lens of inclusivity and respect.

Transmission’s team brings experience, but also representation. Owners/partners Kabir Khanna (who is also programming director), Katii B, Ellie McDyre, and Kelli Kerrigan together previously managed 618 productions, a venue in Chinatown, crafting “some of D.C.’s freakiest parties, raves, and mosh pits” they note.

They packed up operations last fall to a space curated specifically for D.C.’s underground music and culture scene, building their efforts in Chinatown to bring in more fans in queer and POC circles.

Transmission, Khanna points out, is built on DIY values. In the music scene, DIY means that promoters and organizers – often disconnected from the mainstream and part of marginalized communities – build shows and programs collaboratively, but independently from institutions, supporting each other as smaller, independent venues close. Here, Transmission aims to ensure that those putting together these underground inclusive shows have a more permanent and stable home, can have access to resources, and can provide more sustainable income to artists. “We’re trying to get more people to support and enjoy the music, and also give artists and organizers within the DIY community more structure and a larger cut,” says Khanna.

Khanna also notes that Transmission operates “under the principles of safety, inclusivity, and respect.” McDyre added that even at venues that claim inclusivity, that statement might not take place in practice. We’re “not just pitting up a rainbow flag,” says McDyre, but as some of the owners are trans and POC, audiences can see themselves reflected at the top.

Much like the DIY nature of the music community, the Transmission owners brought a DIY ethos to turning around their space.

In March 2020 – the height of COVID lockdowns – Rock & Roll Hotel suddenly shuttered, though not due to the pandemic; instead, the venue claimed that decreasing sales and increasing competition led to the closure. For 14 years, it was the central spot for cheap beer and lesser-known and celebrated acts. The space stood vacant for more than five years, until Transmission turned the power back on.

“When we got into the space, it was effectively abandoned for years,” says Khanna. “There was a ton of mold, and paint primer covering all surfaces. It was nearly falling apart.” Khanna noted that many music venues like this one, regardless of how well it was maintained, “get the shit kicked out of it,” given the nature of shows. The team called in mold removal contractors, ripped up most of the floorboards, and started fresh.

Transmission’s first floor is styled as a stripped-down black box: the better to take in the music. “It’s minimal on purpose to act as a canvas for set design and music,” without a specific aesthetic, says Khanna. Moving upstairs, the second floor has been opened up, removing some walls, and now has a larger dance area than the first floor. Beyond the first two performance levels, and a holdover from Rock & Roll Hotel, is the rooftop. Though without a stage, the rooftop space is filled with murals splashed across the walls, with a full bar. Transmission’s current capacity is 496, but the team is looking to grow that number. Transmission will also leverage the full kitchen that Rock & Roll Hotel operated, bringing in Third Hand Kitchen to offer a variety of food, including vegan and vegetarian options.

Khanna pointed out an upcoming show reflective of Transmission’s inclusive ethos: Black Techo Matters on Feb. 27. The event is set to be “a dynamic, collaborative night of underground electronic music celebrating Black History Month.” Khanna says that techno came from Black music origins, and this event will celebrate this genesis with a host of artists, including DJ Stingray 313, Carlos Souffront, and Femanyst.

a&e features

Meet D.C.’s Most Eligible Queer Singles

Our annual report, just in time for Valentine’s Day

Just in time for Valentine’s Day, the Blade is happy to present our annual Most Eligible Singles issue. The Singles were chosen by you, our readers, in an online nominations process.

John Marsh

Age: 35

Occupation: DJ and Drag Entertainer

How do you identify? Male

What are you looking for in a mate? I’m looking for someone who’s ready to dive into life’s adventures with me. someone independent and building their own successes, but equally open to supporting each other’s dreams along the way. I know that probably sounds simple because, honestly, who isn’t looking for that? But my life and career keep me very social and busy, so it’s important to me to build trust with someone who understands that. I want a partner who knows that even when life gets hectic or I’m getting a lot of attention through my work in the community, it doesn’t take away from my desire to build something real, intentional, and meaningful with the right person.

Biggest turn off: My biggest turnoff is arrogance or judgment toward others. I’m most drawn to people who are comfortable being themselves and who treat everyone with the same level of respect and care. I’ve worked hard for the success I’ve found, but I believe in staying humble and leading with kindness, and I’m attracted to people who live the same way. I’m also turned off by exclusionary mindsets, especially the idea that sapphic folks don’t belong in gay spaces. Our community is vibrant, diverse, and strongest when it’s shared with everyone who shows up with respect and love

Biggest turn on: I’m drawn to people who can confidently walk into new spaces and create connection. Being able to read a room and make others feel comfortable shows emotional intelligence and empathy, which I find incredibly attractive. I also come from a very social, open, and welcoming family environment, so being with someone who embraces community and enjoys bringing people together is really important to me.

Hobbies: I have a lot of hobbies and love staying creative and curious. I’m a great cook, so you’ll never have to worry about going hungry around me. In my downtime, I watch a lot of anime and I will absolutely talk your ear off about my favorites if you let me. I’m also a huge music fan and K-pop lover (listen to XG!), and I’m a musician who plays the cello. I spend a lot of time sewing as well, which is a big part of my creative expression. My hobbies can be a little all over the place, but I just genuinely love learning new skills and trying new things whenever I can.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? This year feels like a huge milestone for me. I’m getting ready to join a tour this summer and want to represent myself well while building meaningful connections in every city I perform in. I’m also focused on growing as a DJ, sharing more mixes and content online, and reaching a big creative goal of releasing original music that I’m producing.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I have a lovely Akita named Grady that I’ve had for 10 years and always want pets in my life. I’m open to kids when/if the time is right with the right person.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? Hell no. I don’t see political differences as just policy disagreements anymore – they often reflect deeper values about how we treat people and support our communities. I’m very progressive in my beliefs, and I’m looking for a partner who shares that mindset. For me, alignment in values like equity, compassion, and social responsibility is non-negotiable in a relationship. To be very clear about my beliefs, I’m outspoken about my opposition to immigration enforcement systems like ICE and believe both political parties have contributed to policies that have caused real harm to vulnerable communities. I’m also deeply disturbed by the ongoing violence in Palestine and believe we need to seriously examine our support of military actions that have resulted in the loss of countless innocent lives. These aren’t abstract political opinions for me, they are moral issues that directly inform who I am and what I stand for.

Celebrity crush: Cocona

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I used to own a catering business in college that paid for my school — I also went to a Christian college, lol.

Jackie Zais

Age: 35

Occupation: Senior director at nonprofit

How do you identify? Lesbian woman

What are you looking for in a mate? Looking for someone who’s curious about the world and the people in it — the kind of person who’s down to explore a new spot one night and stay in with takeout the next. Confident in who they are, social without being exhausting, adventurous but grounded, thoughtful but not pretentious. Someone who can be funny while still taking life (and relationships) seriously.

Biggest turn off: Doesn’t have strong opinions. I love hearing a wild hot take.

Biggest turn on: When someone can make me belly laugh.

Hobbies: Number one will always be yapping with friends over food, but I also love collecting new hobbies. Currently, I crochet (and have some dapper sweater vests as a result), listen to audiobooks on what I personally think is a normal speed (2x) and play soccer and pickleball. But I’ve tried embroidery, papier-mâché, collaging, collecting plants, scrap booking, and mosaic.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? I’ve recently started swimming and I want to look less like a flailing fish and more like someone who knows what they’re doing.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I have neither but open to kids

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? My best friend is a moderate Democrat and that’s as far right as I’m willing to go.

Celebrity crush: Tobin Heath

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I’m the daughter of Little Miss North Quincy 1967.

Kevin Schultz

Age: 39

Occupation: Product manager

How do you identify? Gay

What are you looking for in a mate? You know 2001’s hottest Janet Jackson single, “Someone to Call My Lover?” To quote Janet, “Maybe, we’ll meet at a bar, He’ll drive a funky car; Maybe, we’ll meet at a club, And fall so deeply in love.”

Realistically though, I’d love to find someone who loves to walk everywhere and who avoids the club because it’s too loud and crowded. Later in the song, our songstress opines “My, my, looking for a guy, guy, I don’t want him too shy; But he’s gotta have the qualities, That I like in a man: Strong, smart, affectionate” and I’m quite aligned there – I’m an introvert looking for someone more extroverted.

I’m looking for someone who is different from me. When the math works, one plus one should equal two. Two becoming one is more art, and my relational approach is more science, or, I guess, math.

Biggest turn off: I’m turned off by a lot of superficially small things — chewing with one’s mouth open, dirty or untrimmed fingernails, oh, and also, lack of self awareness. My personal brand of anxiety is hyper self-aware, so I’m very turned off by someone who doesn’t realize that they exist in the world with others.

Biggest turn on: Competency. Or maybe…eyes? So perhaps, you see my conundrum — I’m very engaged by people who are deeply engaged by something, but I’d be lying if I said a sharp gaze and a wink didn’t get me. And, you know, some stamina in all avenues, mental and physical doesn’t hurt either.

Hobbies: Fixing everyone’s WiFi (this did actually get me a date once), and just generally fixing everyone’s everything. If it’s got a plug, screen, or buttons I can probably help you with it. On my own, I’m really into smart home devices and automation, and just to be timely, my latest thing is setting up and tuning my own instance of OpenClaw. (No one should actually do this, which is why I’m trying.) Together, we could also explore such hobbies as visiting every Metro station, visiting and exploring a new airport, and exploring why there are so many gay transit nerds. There’s no non-fake sounding way to say this but I also just love knowledge seeking, so I’d also love to go on an adventure with you where we learn something brand new.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? My biggest goal is to arrive to 2027 just a little better than I arrived to 2026. A few gym goals, a few personal goals, a few work goals; I hope to get a few of them across the finish line. At the risk of holding myself accountable, one of those goals is to be able to flawlessly side plank for over a minute. Please don’t mistake me for a huge gym rat; I just have a questionable relationship with balance and I’m really working on it.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I’ll just be blunt: no pets. Stating this on my Hinge profile resulted in an exponential loss of matches, so it’s very fun to trot out the idea. Primarily, I’m allergic to cats and dogs so my aversion is mostly biological. I’m not, however, allergic to kids — big fan of my various nieces and nephews — but I’d really only consider kids of my own if my chosen companion and I could financially afford them without compromise, and at this age I’ve become opinionated about the life I want to live.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No. This becomes a simpler answer with each passing day, unfortunately.

Celebrity crush: If I’m being of the moment, of course, it’s going to be one of the gentlemen on “Heated Rivalry,” but if I were to really dig into the archives it would be pre-Star Trek Chris Pine. I first saw him in an absolute train wreck of a movie called “Blind Dating” where he plays a blind guy who tries to pretend to be sighted in order to date. The movie was terrible, but I found him irresistible.

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I went suddenly deaf on one side only (my left) just before my 33rd birthday. After a bit of time in the wilderness (metaphorically) I got a cochlear implant a few years later, and it really changed my life. I will talk until someone stops me about hearing, sound, and the amazing arena of hearing loss technology. A lot of people, when they see my implant, assume I was born with hearing loss, so it’s always a bit odd (obscure even!) when I tell people I lost it as an adult. But, I also got my hearing back as an adult and am an eager advocate for assistive technology and visibility for people with disabilities that are not always immediately visible. I also work with prospective adult implant candidates to determine if an implant is right for them, because losing hearing suddenly as an adult is isolating and it’s helpful to talk to someone who’s been there.

Gabriel Acevero

Age: 35

Occupation: Maryland State Delegate

How do you identify? Gay

What are you looking for in a mate? Emotional intelligence and a sense of humor.

Biggest turn off: Fetishization.

Biggest turn on: Kindness and emotional intelligence.

Hobbies: Traveling and reading (I love books).

What is your biggest goal for 2026? More self care. I love what I do but it can also be physically taxing. In 2026, I’m prioritizing more self care.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I have neither but I’m open to both.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No.

Celebrity crush: Kofi Siriboe

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I’m a Scorpio who was raised by a Scorpio and I have many Scorpios in my life.

Vida Rangel

Age: 36

Occupation: Public Servant, Community Organizer

How do you identify? I am a queer transLatina

What are you looking for in a mate? I’m looking for a partner who is caring, socially aware, and passionate about meaningfully improving some part of this world we all live in. Ideally someone playful who can match my mischievous energy, will sing and dance with me whenever joy finds us, and will meet me at protests and community meetings when the moment calls for bold collective action.

Biggest turn off: Ego. Confidence can be cute, but humility is sexy.

Biggest turn on: Drive. Seeing someone put their heart into pursuing their goals is captivating. Let’s chase our dreams together!

Hobbies: Music in all its forms (karaoke, playing guitar, concerts, musicals…), finding reasons to travel to new places, and making (Mexican) tamales for friends and coworkers.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? My biggest goal for 2026 is to organize and a celebratory kiss on election night wouldn’t hurt.

Pets, Kids or Neither? An adorable black cat named Rio (short for Misterio)

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? Ma’am? If you feel the need to ask…

Celebrity crush: Mi amor, Benito Bad Bunny. Zohran Mamdani, too. I have lots of love to give.

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I worked at Chick-fil-A when I was in high school and was fired after just three months. At the time it was still legal to fire someone for being trans, but I’m pretty sure it was because I called out to go to a Halloween party.

Em Moses

Age: 34

Occupation: Publishing

How do you identify? Queer

What are you looking for in a mate? Companionship, passion, fun. I seek a confident partner who inspires me, someone to laugh and dance with, someone with a rich internal universe of interests and experiences to build upon. A lifelong friend.

Biggest turn off: Dishonesty.

Biggest turn on: I love when someone is exactly themselves, nurturing their passions and skills and showing up uniquely in this world as only they can.

Hobbies: I love to read. I create art with my hands. When the weather is nice I’m outside, walking around the District looking at flowers and trees.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? My main goal this year is to spend more time with my nieces and nephews.

Pets, Kids or Neither? No pets or children in my life currently.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? While I consider myself quite openminded and genuinely enjoy learning from perspectives different from my own, I have clear boundaries around my morals and those pillars do not fall.

Celebrity crush: Luigi Mangione

Name one obscure fact about yourself: My first job was at a donut shop.

Nate Wong

Age: 41

Occupation: Strategy adviser to nonprofits and philanthropists to help ambitious ideas turn into meaningful, positive societal impact.

How do you identify? Gay (he/him)

What are you looking for in a mate? An additive partner: sociable, adventurous, and curious about the world. I’m drawn to warmth, openness, and people who show up fully — one-on-one and in community. If you enjoy a good dinner party, make eye contact, and actually talk to strangers (I know a D.C. no-no), we’ll get along just fine.

Biggest turn off: Not being present. Active listening matters to me; attention is a form of respect (and honestly, very attractive). And a picky food eater (how will we some day be joint food-critics?).

Biggest turn on: Curiosity, adventuresome spirit, and someone who can hold their own in a room — and still make others feel at ease. Confidence is best when it’s generous.

Hobbies: Splitting my time between the ceramics studio (District Clay), planning the next trip, and finding great food spots. I box to balance it all out, and I love curating small, adventurous gatherings that bring interesting people together — the kind where you stay later than planned.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? The last few years threw some curve balls. So 2026 is all about moving forward more freely and passionately, trusting what feels right and following it with intention (and joy).

Pets, Kids or Neither? Open to kids (in a variety of forms — already have some adorable god kids). A hypoallergenic dog would absolutely raise the cuddle quotient; cats are best admired from a respectful, allergy-safe distance.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? I value thoughtful listening and sincere debate; shared values around the honoring of everyone’s humanity, equity, and justice matter to me and aren’t up for debate.

Celebrity crush: Bad Bunny style with Jason Momoa humble confidence (harking to my Hawaiian roots) and Idris Elba charm — range matters.

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I celebrated medical clearance by going surfing in El Salvador. I’ve also nearly been arrested in Mozambique and somehow walked away unscathed (and without complying with a bribe) — happy to explain over an excursion.

Diane D’Costa

Age: 29

Occupation: Artist + Designer

How do you identify? Queer/lesbian

What are you looking for in a mate? A cuddle buddy, a fellow jet setter, a muse! Someone to light my soul on fire (in a good way).

Biggest turn off: Apathy. I care deeply about a lot of things and need someone with a similar curiosity and zest for life.

Biggest turn on: Mutuality really does it for me — a push and pull, someone who will throw it back and also catch it. I love someone who takes initiative, shows care and compassion, and expresses fluidity and confidence.

Hobbies: You can find me throwing pottery, painting, sipping natural wine, supporting local coffee shops, and most definitely tearing up a QTBIPOC dance floor.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? Producing my first solo art show. This year I’m really leaning into actualizing all my visions and dreams and putting them out into the world.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I’ve got a Black Lab named Lennox after the one and only D.C. icon, Ari Lennox. I love supporting the youth and (made a career out of it), but don’t necessarily need to have little ones of my own.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No. Values alignment is key, but if you wanna get into the nuances of how we actualize collective liberation let’s get into it.

Celebrity crush: Queen Latifah

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I’m in the “Renaissance” movie. I know, I know slight flex… but “Crazy In Love” bottom left corner for a split second and a harsh crop, but I’m in there. “You are the visuals, baby” really hit home for me.

Donna Marie Alexander

Age: 67

Occupation: Social Worker

How do you identify? Lesbian

What are you looking for in a mate? Looking for a smart, kind, emotionally grown woman who knows who she is and is ready for real companionship. Also, great discernment and a good lesbian processor. Bonus points if you’ll watch a game with me— or at least cheer when I do. Extra bonus if you already know that women’s sports matter.

Ideal first date: Out for tea or a Lemon Drop that turns into dinner, great conversation, and a few laughs. Low drama, high warmth.

Must haves: A sense of humor, curiosity about the self, curiosity about me, and curiosity about the world. An independence, and an appreciation for loyalty—on and off the field. Dealbreaker: Anyone who thinks “it’s just a game.”

Biggest turn off: Self-centered and a lack of discernment.

Biggest turn on: Great conversation and a sense of humor.

Hobbies: Watching the Commanders game

What is your biggest goal for 2026? Self-growth and meeting an amazing friend.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I have two kids and grandkids.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No

Celebrity crush: Pam Grier

Name one obscure fact about yourself: She’s way more superstitious about game-day routines than she lets on

Joe Reberkenny

Age: 24

Occupation: Journalist

How do you identify? Gay

What are you looking for in a mate? Someone who’s driven, flexible, and independent. I’m a full-time journalist so if there’s news happening, I’ve gotta be ready to cover breaking stories. I’m looking for someone who also has drive in their respective career and is always looking to the future. I need someone who gets along with my friends. My friends and community here are so important to me and I’m looking for someone who can join me in my adventures and enjoys social situations.

Biggest turn off: Insecurity and cocky men. Guys who can’t kiki with the girls. Early bedtimes.

Biggest turn on: Traits: Emotional stability and reliability. A certain sense of safety and trust. Someone organized and open to trying new things. Physical: Taller than I am (not hard to do at 5’7″) but also a preference for hairy men (lol). Someone who can cook (I am a vegetarian/occasional pescatarian and while it’s not a requirement for me in a partner it would need to be something they can accommodate).

Hobbies: Exploring D.C. — from museums to nightlife, reading (particularly interested in queer history), dancing, frolicking, playing bartender, listening to music (preferably pop), classic movie connoisseur (TCM all the way).

What is your biggest goal for 2026? Continue my work covering LGBTQ issues related to the federal government, uplift queer voices, see mother monster (Lady Gaga) in concert.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I’ve got neither but I love a pet.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No

Celebrity crush: Pedro Pascal

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I’ve been hit by multiple cars and I have a twin sister.

a&e features

Marc Shaiman reflects on musical success stories

In new memoir, Broadway composer talks ‘Fidler,’ ‘Wiz,’ and stalking Bette Midler

If you haven’t heard the name Marc Shaiman, you’ve most likely heard his music or lyrics in one of your favorite Broadway shows or movies released in the past 50 years. From composing the Broadway scores for Hairspray and Catch Me if You Can to most recently working on Only Murders in the Building, Hocus Pocus 2, and Mary Poppins Returns, the openly queer artist has had a versatile career — one that keeps him just an Oscar away from EGOT status.

The one thing the award-winning composer, lyricist, and writer credits with launching his successful career? Showing up, time and time again. Eventually, he lucked out in finding himself at the right place at the right time, meeting industry figures like Rob Reiner, Billy Crystal, and Bette Midler, who were immediately impressed with his musical instincts on the piano.

“Put my picture under the dictionary definition for being in the right place at the right time,” Shaiman says. “What I often try to say to students is, ‘Show up. Say yes to everything.’ Because you never know who is in the back of the theater that you had no idea was going to be there. Or even when you audition and don’t get the part. My book is an endless example of dreams coming true, and a lot of these came true just because I showed up. I raised my hand. I had the chutzpah!”

Recalling one example from his memoir, titled Never Mind the Happy: Showbiz Stories from a Sore Winner ( just hit bookshelves on Jan. 27), Shaiman says he heard Midler was only hiring Los Angeles-based artists for her world tour. At the young age of 20, the New York-based Shaiman took a chance and bought the cheapest flight he could find from JFK. Once landing in L.A., he called up Midler and simply asked: “Where’s rehearsal?”

“Would I do that nowadays? I don’t know,” Shaiman admits. “But when you’re young and you’re fearless … I was just obsessed, I guess you could say. Maybe I was a stalker! Luckily, I was a stalker who had the goods to be able to co-create with her and live up to my wanting to be around.”

On the occasion of Never Mind the Happy’s official release, the Bladehad the opportunity to chat with Shaiman about his decades-spanning career. He recalls the sexual freedom of his community theater days, the first time he heard someone gleefully yell profanities during a late screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and why the late Rob Reiner was instrumental to both his career and his lasting marriage to Louis Mirabal. This interview has been edited and condensed.

BLADE: Naturally, a good place to start would be your book, “Never Mind the Happy.” What prompted you to want to tell the story of your life at this point in your career?

SHAIMAN: I had a couple of years where, if there was an anniversary of a movie or a Broadway show I co-created, I’d write about it online. People were always saying to me, “Oh my God, you should write a book!” But I see them say that to everybody. Someone says, “Oh, today my kitten knocked over the tea kettle.” “You should write a book with these hysterical stories.” So I just took it with a grain of salt when people would say that to me. But then I was listening to Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ podcast, and Jane Fonda was on talking about her memoir — not that I’m comparing myself to a career like Jane Fonda’s — but she felt it was time to take a life review. That really stuck in my head. At the time, I was sulking or moping about something that had not gone as well as I wished. And I guess I kind of thought, “Let me look back at all these things that I have done.” Because I have done a lot. I’m just weeks short of my 50th year in show business, despite how youthful I look! I just sat down and started writing before anyone asked, as far as an actual publisher.

I started writing as a way to try to remind myself of the joyous, wonderful things that have happened, and for me not to always be so caught up on what didn’t go right. I’ve been telling some of these stories over the years, and it was really fun to sit down and not just be at a dinner party telling a story. There’s something about the written word and really figuring out the best way to tell the story and how to get across a certain person’s voice. I really enjoyed the writing. It was the editing that was the hard part!

BLADE: You recall experiences that made you fall in love with the world of theater and music, from the days you would skip class to go see a show or work in regional productions. What was it like returning to those early memories?

SHAIMAN: Wonderful. My few years of doing community theater included productions that were all kids, and many productions with adults, where I was this freaky little 12-year-old who could play show business piano beyond my years. It was just bizarre! Every time a director would introduce me to another cast of adults, they’d be like, “Are you kidding?” I’d go to the piano, and I would sightread the overture to Funny Girl, and everybody said, “Oh, OK!” Those were just joyous, wonderful years, making the kind of friends that are literally still my friends. You’re discovering musical theatre, you’re discovering new friends who have the same likes and dreams, and discovering sex. Oh my god! I lost my virginity at the opening night of Jesus Christ Superstar, so I’m all for community theater!

BLADE: What do you recall from your early experiences watching Broadway shows? Did that open everything up for you?

SHAIMAN: I don’t remember seeing Fiddler on the Roof when I was a kid, but I remember being really enthralled with this one woman’s picture in the souvenir folio — the smile on her face as she’s looking up in the pictures or looking to her father for approval. I always remember zooming in on her and being fascinated by this woman’s face: turns out it was Bette Midler. So my love for Bette Midler began even before I heard her solo records.

Pippin and The Wiz were the first Broadway musicals I saw as a young teenager who had started working in community theater and really wanted to be a part of it. I still remember Pippin with Ben Vereen and all those hands. At the time, I thought getting a seat in the front row was really cool — I’ve learned since that it only hurts your neck, but I remember sitting in the front row at The Wiz as Stephanie Mills sang Home. Oh my god, I can still see it right now. And then I saw Bette Midler in concert, finally, after idolizing her and being a crazed fan who did nothing but listen to her records, dreaming that someday I’d get to play for her. And it all came true even before I turned 18 years old. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time, and met one of her backup singers and became their musical director. I was brought to a Bette Midler rehearsal. I still hadn’t even turned 18, she heard me play and said, “Stick around.” And I’ve stuck around close to 55 years! She’s going to interview me in L.A. at the Academy Museum. Would I have ever thought that Bette Midler would say yes to sitting with me, interviewing me about my life and career?

BLADE: That’s amazing. Has she had a chance to read the book yet?

SHAIMAN: She read it. We just talked yesterday, and she wants to ask the right questions at the event. And she even said to me, “Marc, I wasn’t even aware of all that you’ve done.” We’ve been great friends for all these years, but sometimes months or almost years go by where you’re not completely in touch.