homepage news

For Buttigieg, being gay a boost on the campaign trail

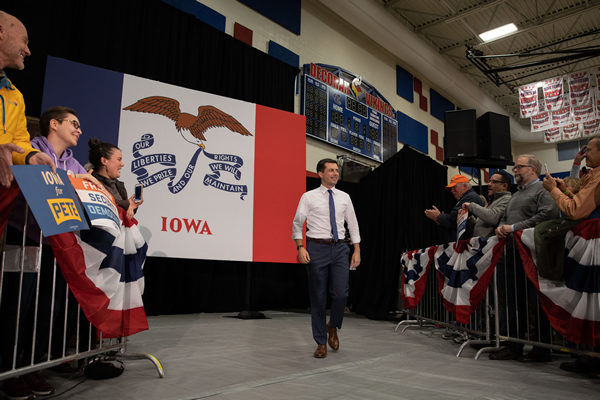

Gay candidate electrifies crowds in Iowa as new polls show him in the lead

CHARLES CITY, Iowa — He’d been going for days, fielding endless queries from voters at campaign stops on everything from health care and gun control to whether he plays Dungeons & Dragons. (He doesn’t, but plays board games like Risk.) But asked pointedly whether evangelicals would ever back a gay candidate, Pete Buttigieg didn’t miss a beat.

“I’m from Indiana, right?” he said to laughter in the crowd. “I know a little bit about what you’re talking about.”

Over the course of South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s three-day campaign bus tour across Iowa, there was no escaping the realization the 2020 presidential hopeful is gay.

But it wasn’t because Buttigieg was wearing his sexual orientation on his sleeve, or waving a rainbow Pride flag on stage at his rallies. It wasn’t because he hectored his audience to back his candidacy based on the unprecedented nature of an openly gay presidential contender in the race for the Democratic nomination.

It was because the audience kept bringing it up and cheered him on for it. Coming off his success at the Liberty & Justice Celebration for Democratic presidential candidates on Nov. 1, Buttigieg lit up crowds over the course of his campaign tour — and being an openly gay candidate was a big part of that welcome reception.

After long bus rides with views of cornfields and big Iowa skies, LGBTQ issues and the prospect of having a gay man in the White House were brought up by the audience, not by the 37-year-old presidential hopeful, in four of the five public events on Buttigieg’s tour.

At Charles City, Buttigieg recounted his story of coming out. In June 2015, as Buttigieg was running for re-election as mayor, he disclosed his sexual orientation for the first time publicly in an essay for the South Bend Tribune.

“As hard as it was for me deciding what to do when I came out — and it was an election year by the way, we didn’t know what the effect was going to be — I just knew in my life, it was time,” Buttigieg said. “And what happened was I got re-elected with 80 percent of the vote, even in Indiana when Mike Pence was governor of our state.”

The audience ate it up, responding with applause and cheers that lasted several seconds. Building off that response, Buttigieg made a joke involving Chasten Buttigieg, his now husband whom he married last year.

“He couldn’t get through the milk aisle at the grocery without hearing about potholes and all these things,” Buttigieg continued, in a seeming attempt to make his family life more relatable. “We invited people to treat us like any other couple, and 99 times out of 100, they did.”

That’s where Buttigieg made his shift. Run-of-the-mill issues like potholes, he said, are what Americans are concerned about, not the prospects of a gay couple in the White House.

“What I’m finding is the real question on voters’ minds is how their lives are going to be different when I’m president versus the one we’ve got, or one of the competitors,” he said.

Buttigieg conceded he’s “happy to tell my story and I’m proud of who I am,” but wants to focus on the bread-and-butter issues Americans are facing.

“This is part of how we break the spell of the current president: It’s not all about me, it’s not all about him, though there are many things we might point out about his deficiencies,” Buttigieg said. “But the more we’re talking about him or me the less we’re talking about you. And when we’re talking about you, we’re winning, because we’ve got the right answers for our lives.”

That answer struck a chord with attendees, who responded with cheers and applause. It also exemplifies the way Buttigieg approached the issue of being gay on his campaign tour: Wait for the audience to bring it up, acknowledge it, stand for applause then shift back to bread-and-butter issues or the main campaign message.

It would be a historic first having an openly gay president, and that’s inspiring supporters in the same way the idea of electing the first black president helped Barack Obama and the idea of sending a woman to the White House helped Hillary Clinton.

William Reinicke, a 19-year-old student at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who came to hear Buttigieg speak at a fish fry event in Cedar Rapids, said the South Bend mayor is his No. 1 choice for president because he “represents generational change,” and being openly gay is one aspect of that.

“I think that’s a plus in the sense that it shows that no matter what your background is, no matter what your orientation is, that you can make it to whatever level possible that there is in this country,” Reinicke said.

The most powerful example of this phenomenon — and perhaps the most highly publicized in the media — was the last question Buttigieg took at a rally Saturday evening in Decorah, where an audience member — through a note passed to a campaign staffer — asked how he’d deal with international leaders from countries “like Saudi Arabia and Russia, where it’s illegal to be gay.”

“So, they’re going to have to get used to it,” Buttigieg said succinctly.

A full 27 seconds of applause followed. It was the loudest and longest applause for any response that night. Other responses from the crowd of 1,000 to Buttigieg’s lines about action on guns and removing President Trump from the White House were loud, but didn’t come close.

Although Buttigieg cautioned, “we can’t intervene in every country and make them be good to their people,” he said his election as president would have an impact on LGBTQ people overseas.

“I do believe that one big step forward would be for a country like the United States to be led by somebody that people in those other countries can look to and know that they’re not alone,” Buttigieg concluded.

Buttigieg, asked by the Blade on the campaign trail whether he’s surprised being gay has energized his crowds, said he’s seen a lot of older individuals “who have a kid or maybe a niece or nephew who comes out and is gay and trans” seeking to have a better understanding of LGBTQ people.

“This campaign has helped that,” Buttigieg said. “So, it’s not only that it, I think, sends a message in particular a lot of youth that they belong and they have a place, but also for a lot of adults with relationships with LGBTQ youth, and then of course a lot of people from an older generation who are LGBTQ just never thought they’d live to see this day.”

Buttigieg added, “It has been striking to me how many people it touches in different ways.”

He’s certainly connecting with Iowans. A Quinnipiac poll published on Nov. 7 found he’s essentially tied in the state with Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) among likely Iowa caucus-goers. Warren has support from 20 percent, followed by Buttigieg at 19 percent, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) at 17 percent and former Vice President Joseph Biden at 15 percent. And a Monmouth University poll released Tuesday shows Buttigieg atop the field in Iowa with 22 percent support, followed by Biden at 19, Warren with 18 and Sanders with 13 percent.

Faith and passion

Of course, being gay isn’t the only personal attribute inspiring Buttigieg’s supporters, many of whom are also impressed with his credentials at just 37 years old. After all, Buttigieg is a Harvard-educated Rhodes scholar who’s also an Afghanistan war veteran and a former McKinsey management consultant.

For Linda Langston, a 66-year-old former member of the Lake County Board of Supervisors who attended a Cedar Rapids fish fry wearing a “Pete 2020” campaign sticker, Buttigieg’s sexual orientation is no big deal.

“It’s fine,” Langston said. “I mean, my oldest son is gay, so I get it, but that is not what to me is the defining factor, the defining factor is that he’s a really bright, articulate person who has served his country in war, and can come back and speak with hard faith and passion.”

Cindy Schubert, a 73-year-old Iowa voter who showed up on a Monday afternoon for a meet-and-greet with Buttigieg in Algona, Iowa, brought up the candidate’s youth when asked by the Blade if he’s championing any issues she supports.

“I guess I like the fact that he’s very energetic and young, you know, but at the same time, I’m leaning towards Joe because of his experience,” Schubert said. “So I’m really torn.”

Although the meet-and-greet event in Algona, hosted by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, attracted an older crowd than Buttigieg’s usual audiences, Schubert said he’s “got a lot of support in this community.”

“I think he’s got more support than anybody else,” Schubert said.

But Buttigieg’s youth cuts both ways in the Democratic primary, as evidenced by a recent New York Times article on Buttigieg indicating his gushing press and expansive donor base are riling his Democratic rivals, who say he’s inexperienced.

At a subsequent rally in Spencer, Buttigieg sought to allay concerns about his youth and inexperience in response to a question from an attendee.

“It’s true that I have not been marinating around Capitol Hill,” Buttigieg said. “I’d argue that might be a virtue at a time like this.”

Following applause, Buttigieg said he does have experience “on the ground, dealing with problems as a mayor.”

“And one of the things about being a mayor is you are on the ground getting stuff done, we deal with some of the biggest and toughest issues in the country from infrastructure, economic development, from disasters, to getting the 3 a.m. phone call, to planning for the long run racial issues all the way through to infrastructure underground,” Buttigieg said.

To laughter, Buttigieg continued, “You don’t get to call fake news if somebody says that the snow didn’t get plowed, either it did or it didn’t. People are going to know.”

At times, the connection between Buttigieg’s supporters and the gay presidential candidate was poignant, such as when the campaign tour came to Mason City.

On one hand, the city has the distinction of being the town on which “River City” in the classic musical “Music Man” is based and the site where the rock ‘n roll pioneers Big Bopper, Ritchie Valens and Buddy Holly met their end in a plane crash in 1959.

On the other hand, Mason City was also the first stop on the Buttigieg tour within the congressional district of Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa), whose notoriously anti-LGBTQ views have animated his career and whom Congress recently censured for comments in favor of white nationalism.

LGBTQ people knew about King long before he expressed white nationalism sympathies. Among other things, King in 2010 successfully led the effort to oust by referendum three judges from the Iowa Supreme Court who ruled in favor of same-sex marriage.

Nonetheless, in his stop in King’s district, an audience member presented Buttigieg with an LGBTQ question: What would he do for LGBTQ youth?

‘I was alone’

In response, Buttigieg said winning marriage equality nationwide four years ago “doesn’t mean the job is done,” pointing to the importance of passing federal LGBTQ comprehensive non-discrimination legislation known as the Equality Act.

“It’s a basic matter of fairness, it’s the right thing to do, and I will sign it when it gets to my desk,” Buttigieg added to loud hoots and applause.

Buttigieg pointed out an estimated 40 percent of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ and said LGBTQ kids are more likely to have mental health problems and commit suicide.

“We got to make sure that we wrap around young people with compassion,” Buttigieg said to applause.

His response included a personal touch.

“There were exactly zero out students at my high school,” Buttigieg said. “I was starting to realize I was different, I was alone, and you need to know you’re not alone, you’re not the only one and everybody in the name of compassion ought to support that.”

As he wrapped up in Mason City, Buttigieg said he could embrace policies to advance LGBTQ rights all day long, but emphasized the importance of belonging — a core general message of his campaign.

“It’s not just policy,” Buttigieg said. “It’s about the example we send, and the message we send. The message we send is you belong and we love you, and we want to belong.”

Buttigieg once again followed the pattern of embracing support for LGBTQ identity before moving to a more general theme, this time with an emotional, almost biblical, appeal that seemed well suited for the audience. And again, Buttigieg won resounding applause.

Among the attendees at the Mason City event was Adam Lewis, a 41-year-old social worker who’s gay and volunteers for the Buttigieg campaign.

“He just magnetic,” Lewis said, “and I wanted to make sure that as many people as I know could also hear him because I know as soon as you hear him and hear his values and what he stands for, and how he’s going to make sure that everyone belongs in this campaign, that’s all they need to hear.”

Lewis, who said the results of the 2016 election “didn’t make sense” to him, said living in King’s district makes Buttigieg a breath of fresh air simply because he’s “someone reasonable, and not racist or homophobic.”

“I think people fear change,” Lewis said. “I’m hoping that a lot has changed since the last election, and people are opening their eyes and realizing that we have to have change. It’s not something to fear, it’s something we need.”

Asked if having gay presidential candidate is important to him as a gay man, Lewis said, “it’s not that it’s not important, because who we are and who we love is a central to who we are as human beings,” but added there’s more to it.

“It’s about bringing reason and responsibility back to Washington and letting a new generation of people fix the mess that was created over the last several decades,” Lewis said.

After the Mason City event, Buttigieg told the Blade that finding a warm reception in conservative areas like King’s district is “really encouraging” and demonstrates the appeal of the Democratic Party’s views in unlikely places.

“Part of what I think is really important is to let a lot of people who maybe think they’re the only one in their community or office of family or church pew who sympathizes with Democrats to realize they’re not the only ones, to kind of build a community around these values,” Buttigieg said.

Buttigieg also said holding events in conservative areas builds off his theme of unity — a major message he’s articulated in his campaign.

“It’s not that we’re going to get everyone to agree,” Buttigieg said. “It’s that there’s a lot more room for us to grow than you would think, but you got to show up, and that’s one of the reasons why it’s important for me to campaign in an area like this.”

Trouble in the South

The idea of a gay presidential candidate might not play as well in other early states in the Democratic primary. In fact, there’s good evidence being gay could hurt him in the South, which is essential territory for any candidate to secure the Democratic nomination.

Late last month, The State, a South Carolina-based newspaper, published a memo on internal Buttigieg campaign focus groups indicating black voters in South Carolina find the candidate’s sexual orientation a barrier to supporting him. Additional stories were published in Politico and the New York Times to the same effect.

Buttigieg told the Blade he doesn’t think his sexual orientation “has to be an obstacle” for black voters, but understands “there’s clearly a life journey within a lot of church communities, and a lot of generational dynamics.”

Even though the issue isn’t going away, Buttigieg said he thinks he can deliver for black voters based on his policy positions, which include a “Douglass Plan” to rectify racial injustice.

“I think voters, and in particular black voters who have felt both abused by the Republican Party, but also taken for granted by the Democratic Party, they just want to know if there are going to be results,” Buttigieg said. “And if I can demonstrate that, then a lot of the other stuff falls away.”

Asked by the Blade whether the internal focus group published by the State was an authorized leak, Buttigieg denied it was the case. In response to another reporter’s question about whether similar focus groups were commissioned in other states, Buttigieg said he’ll “let others talk to focus group stuff.”

Alvin McEwen, a South Carolina-based blogger who’s gay and black, said black voters are more concerned about Trump than Buttigieg and would support the candidate if he were the Democratic nominee.

“This speculation about homosexuality and the black community is nothing more than a generalization about the black voter and our community in general,” McEwen added. There are nuances that people always miss. Not all black church folk oppose homosexuality. Some actually support the LGBTQ community. They are either LGBTQ or have LGBTQ relatives. They tend to be silent because the prevailing belief is that the black community is homophobic and they aren’t going to rock that boat.”

Even on the Iowa trip, there was one instance where Buttigieg’s sexual orientation — as well as his youth — ended up being the elephant in the room as opposed to energizing his candidacy.

At the Abby Finkenauer Fish Fry in Cedar Rapids, amid the pungent aroma in the air of fried food, an awkward moment ensued when the three union leaders who were moderating — three older men with a “no nonsense” vibe — asked him about infrastructure.

Confessing he’s actually surprised Trump didn’t fulfill his pledge, Buttigieg said infrastructure is important, even the “less sexy” aspects like wastewater management. Coincidentally, one of the moderators for the discussion was representing the plumbers union and said wastewater was “pretty sexy.”

Buttigieg shrugged it off with a laugh and said, “Oh yeah?” But the awkwardness continued when another moderator said he wanted to discuss the topic of bridge construction, which he said iron workers find “real sexy.”

Touring an ethanol plant

Being a gay presidential candidate straight-up wasn’t a factor in Iowa when the focus on the campaign trip was business, such as Buttigieg’s trip to an ethanol plant in Mason City.

Donned with a blue hard hat and goggles, Buttigieg inspected the facility, including the laboratory and a room with computer screens monitoring the fermenters, asking questions about best practices and economic policies that would benefit the business.

Promoting the facility, which mixes ethanol into petrol to extend its use, Golden Grain Commodity Manager Curt Strong touted exports and the plant’s enhanced environmental practices.

Asked by the Blade during the tour how Trump’s trade wars were affecting business, Strong said the important thing is for Congress to pass the United States-Mexico-Canada trade deal, or USMCA, which he said would be a “great first step.” Otherwise, Strong said tariffs in China and Brazil were problematic.

“So some of our bigger customers were penalizing us for shipping product to their countries where we could tell they wanted the product,” Strong said. “So the trade wars, it would be great to get them solved. It would be great for us to have a level playing field. But I think there’s a lot of negotiation that needs to go on there.”

Concluding the presentation, Buttigieg said biofuels like those produced at Golden Grain could be part of American’s future, but “you got to have policy that supports that” as well as policy consistency.

“And the added uncertainty that’s coming from this administration has just created more problems that really haven’t gotten folks here,” Buttigieg said. “Now you’re working around the uncertainty, you’re working through the regulation, but I got to think that it would be extraordinary to think of what could be unlocked if you had another 15 years ahead of you to innovate the way you did last 15 years without some of these things being thrown at you from Washington, D.C.”

On one occasion, Buttigieg broke his own pattern by bringing up his sexual orientation himself — during a forum on disabilities in Cedar Rapids.

Touting his newly unveiled comprehensive plan for the disabled, which includes doubling employment among disabled people by 2030, Buttigieg brought up being gay no fewer than three times.

Addressing the crowd of advocates for people with disabilities, Buttigieg said many Americans “have been put on the wrong fence of belonging” and he “felt this in one very particular way in my own life,” making an allusion to his sexual orientation without explicitly bringing it up.

Asked about the high suicide rate, Buttigieg said he was glad the question came up because he belongs to “actually a couple communities — as a gay veteran — that remind me that there are some communities in America that are disproportionately liable to die by suicide.”

Buttigieg also drew a comparison between LGBTQ people and people with disabilities, saying members of both communities cut across all demographics.

“I reflected once as a member of the LGBT community, I thought, you know, one thing that’s really special about our community is it’s a minority that is kind of evenly distributed — as far as I can guess — across every geography and race and income group and family background and profession. And then, and then it was pointed out to me that that’s not just true of that community, that’s also true of the disability community.”

As a result, Buttigieg said “at a moment when we are frighteningly fractured as a country,” the disabled community — like the LGBTQ community — is “an exceptionally diverse, internally diverse community” that can use its political forces to hold public officials accountable to its needs.

“And I hope you find that the opportunity to provide some of that crucial, knitting back together the social fabric of this country, that I, as I hopefully become president will be relying on the American people to do as we pick up the pieces that first day after the Trump presidency has come to an end,” Buttigieg said.

Another exception was during a rally in Waverly, Iowa, when Buttigieg brought up his coming out story in response to a question from a young girl who asked him to name a time in his life he did something that was the right thing to do, but unexpected.

It was also a time when Buttigieg most poignantly described his feelings behind his decision to come out in 2015. Initially, Buttigieg responded to the question by saying it was consistent with his expectation for candidates pursuing office, offering an idealistic vision for the values they should uphold.

“That’s a really important quality for somebody running for office because that’s part of how you earn your paycheck when you’re in office,” Buttigieg said. “It’s to know — look, when you run for office, you want to win, but if you don’t know what matters more to you than winning, then you should not be in office.”

After talking about signing on in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook shooting in 2015 to Mayors Against Illegal Guns, Buttigieg shifted to coming out as he was pursuing re-election as South Bend mayor.

“The decision to come out, I guess was not expected, it wasn’t you know a battle of right versus wrong, but it felt like a battle inside me because I didn’t know what was going to happen,” he said.

There was extended applause and cheers of approval.

Back on the bus, Buttigieg was asked by the Blade how and when he makes the decision to bring up being gay as opposed to letting his audience do it. The South Bend mayor said the planning is “not always super-intentional, right?”

“It comes out just over the course of me talking about my life, and certain things remind me of it,” Buttigieg said. “So with the disability community, it reminds me of it because you have this really interesting phenomenon both with the disability and with the LGBTQ world of this minority, if you will, that cuts through every other group.”

Buttigieg concluded by acknowledging that being gay will likely come up one way or the other on the campaign trail.

“As you know, no two of my stumps are kind of alike because I just kind of go with it, but if I don’t raise it, somebody usually will, so one way or the other, I know it’s part of what we will talk about,” Buttigieg said. “It doesn’t define those appearances, but it’s also something I’m happy to talk about.”

Although being a gay presidential candidate was a major component of the Iowa trip, Buttigieg’s spouse, Chasten Buttigieg, was only present for half of it and no part of the official bus tour. According to the Buttigieg campaign, Chasten was at the pre-event rally and attended the Liberty & Justice Dinner with Buttigieg, then went to Nevada as a campaign surrogate.

On trans healthcare

At his final rally in Spencer, Iowa, Buttigieg again was asked about LGBTQ issues: What would he do as president for LGBTQ youth, especially those who are transgender in medical care?

The question was the last one at the rally, and the last one for his bus tour. It was a fitting end to a bus tour where having an openly gay presidential candidate was a major theme.

“This is obviously an issue of personal importance to me, having grown up, not knowing if I would ever fit in because I was different,” Buttigieg said. “I didn’t know if my own community would have a place for me, and some great things have happened, some great steps forward with that in this country.”

Embracing the U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2015 in favor of same-sex marriage, Buttigieg continued, “I don’t think I would have guessed at the beginning of the same decade that we’re living in that it would be possible for me to stand in front of you a married man running for president of the United States.”

He name-checked the Equality Act, then pointed out the questioner asked specifically about transition-related care for transgender youth. Transgender Americans, Buttigieg said, are “facing a lot of obstacles.”

“We got to make sure that health care is equitable, that everybody can get the care that they need, including gender-affirming care,” Buttigieg said. “That’s part of what it means to be healthy.”

With respect to kids in schools, Buttigieg said, “High school is hard enough if you’re not transgender to navigate. If you are we need to make sure that we’re tearing down the obstacles to belong and be able to get through your day.”

Finally, recognizing Iowa was in 2009 among the first states in the country to legalize same-sex marriage, Buttigieg concluded by thanking Iowans to another round of applause. It was the last line of his remarks before he announced his departure.

“I know the progress that is possible, again, because of things that have become possible in this country that I never would have guessed,” Buttigieg said. “And by the way, thank you Iowa for what you did to help blaze the trail for marriage equality.”

That line may be key to understanding the excitement behind his candidacy. Iowans believe their state has led the way for civil rights, paving the way for LGBTQ rights in 2009, when the Iowa Supreme Court legalized marriage equality, and the election of the first black president the year before, when Barack Obama emerged as the victor in the Iowa caucuses.

For Iowans, Buttigieg’s candidacy represents the opportunity to marry the two. Time will tell if that happens when the Iowa primary caucuses take place on Feb. 3.

Courtney Reyes, executive director of the LGBT group One Iowa, affirmed Buttigieg’s potential to make history as a gay presidential candidate fits in well with the state’s progressive past.

“For many LGBTQ Iowans and allies, even those who plan to caucus for a different candidate, Buttigieg’s candidacy and positive reception is a sign that our state’s progressive history on LGBTQ rights can’t be erased entirely by recent setbacks,” Reyes said. “We Iowans take our ‘first in the nation’ status very seriously, and the caucuses represent a galvanizing opportunity to advance equality for all. No matter what specific candidate they support, LGBTQ Iowans and allies are mobilizing to defend our community during the caucuses and beyond.”

Buttigieg ended his three-day tour by interacting with the crowd in Spencer along the rope line before the stage, shaking hands and taking selfies. After shaking hands with two children in the crowd, before posing with them and their parents for a picture, Buttigieg made his last act for his tour waving to the crowd as he made his exit.

The campaign tour in Iowa had come to an end, and just as Buttigieg credited the state with blazing a trail for LGBTQ rights, Buttigieg’s ability to blaze a trail as a gay presidential hopeful was all the more evident.

homepage news

Honoring the legacy of New Orleans’ 1973 UpStairs Lounge fire

Why the arson attack that killed 32 gay men still resonates 50 years later

On June 23 of last year, I held the microphone as a gay man in the New Orleans City Council Chamber and related a lost piece of queer history to the seven council members. I told this story to disabuse all New Orleanians of the notion that silence and accommodation, in the face of institutional and official failures, are a path to healing.

The story I related to them began on a typical Sunday night at a second-story bar on the fringe of New Orleans’ French Quarter in 1973, where working-class men would gather around a white baby grand piano and belt out the lyrics to a song that was the anthem of their hidden community, “United We Stand” by the Brotherhood of Man.

“United we stand,” the men would sing together, “divided we fall” — the words epitomizing the ethos of their beloved UpStairs Lounge bar, an egalitarian free space that served as a forerunner to today’s queer safe havens.

Around that piano in the 1970s Deep South, gays and lesbians, white and Black queens, Christians and non-Christians, and even early gender minorities could cast aside the racism, sexism, and homophobia of the times to find acceptance and companionship for a moment.

For regulars, the UpStairs Lounge was a miracle, a small pocket of acceptance in a broader world where their very identities were illegal.

On the Sunday night of June 24, 1973, their voices were silenced in a murderous act of arson that claimed 32 lives and still stands as the deadliest fire in New Orleans history — and the worst mass killing of gays in 20th century America.

As 13 fire companies struggled to douse the inferno, police refused to question the chief suspect, even though gay witnesses identified and brought the soot-covered man to officers idly standing by. This suspect, an internally conflicted gay-for-pay sex worker named Rodger Dale Nunez, had been ejected from the UpStairs Lounge screaming the word “burn” minutes before, but New Orleans police rebuffed the testimony of fire survivors on the street and allowed Nunez to disappear.

As the fire raged, police denigrated the deceased to reporters on the street: “Some thieves hung out there, and you know this was a queer bar.”

For days afterward, the carnage met with official silence. With no local gay political leaders willing to step forward, national Gay Liberation-era figures like Rev. Troy Perry of the Metropolitan Community Church flew in to “help our bereaved brothers and sisters” — and shatter officialdom’s code of silence.

Perry broke local taboos by holding a press conference as an openly gay man. “It’s high time that you people, in New Orleans, Louisiana, got the message and joined the rest of the Union,” Perry said.

Two days later, on June 26, 1973, as families hesitated to step forward to identify their kin in the morgue, UpStairs Lounge owner Phil Esteve stood in his badly charred bar, the air still foul with death. He rebuffed attempts by Perry to turn the fire into a call for visibility and progress for homosexuals.

“This fire had very little to do with the gay movement or with anything gay,” Esteve told a reporter from The Philadelphia Inquirer. “I do not want my bar or this tragedy to be used to further any of their causes.”

Conspicuously, no photos of Esteve appeared in coverage of the UpStairs Lounge fire or its aftermath — and the bar owner also remained silent as he witnessed police looting the ashes of his business.

“Phil said the cash register, juke box, cigarette machine and some wallets had money removed,” recounted Esteve’s friend Bob McAnear, a former U.S. Customs officer. “Phil wouldn’t report it because, if he did, police would never allow him to operate a bar in New Orleans again.”

The next day, gay bar owners, incensed at declining gay bar traffic amid an atmosphere of anxiety, confronted Perry at a clandestine meeting. “How dare you hold your damn news conferences!” one business owner shouted.

Ignoring calls for gay self-censorship, Perry held a 250-person memorial for the fire victims the following Sunday, July 1, culminating in mourners defiantly marching out the front door of a French Quarter church into waiting news cameras. “Reverend Troy Perry awoke several sleeping giants, me being one of them,” recalled Charlene Schneider, a lesbian activist who walked out of that front door with Perry.

Esteve doubted the UpStairs Lounge story’s capacity to rouse gay political fervor. As the coroner buried four of his former patrons anonymously on the edge of town, Esteve quietly collected at least $25,000 in fire insurance proceeds. Less than a year later, he used the money to open another gay bar called the Post Office, where patrons of the UpStairs Lounge — some with visible burn scars — gathered but were discouraged from singing “United We Stand.”

New Orleans cops neglected to question the chief arson suspect and closed the investigation without answers in late August 1973. Gay elites in the city’s power structure began gaslighting the mourners who marched with Perry into the news cameras, casting suspicion on their memories and re-characterizing their moment of liberation as a stunt.

When a local gay journalist asked in April 1977, “Where are the gay activists in New Orleans?,” Esteve responded that there were none, because none were needed. “We don’t feel we’re discriminated against,” Esteve said. “New Orleans gays are different from gays anywhere else… Perhaps there is some correlation between the amount of gay activism in other cities and the degree of police harassment.”

An attitude of nihilism and disavowal descended upon the memory of the UpStairs Lounge victims, goaded by Esteve and fellow gay entrepreneurs who earned their keep via gay patrons drowning their sorrows each night instead of protesting the injustices that kept them drinking.

Into the 1980s, the story of the UpStairs Lounge all but vanished from conversation — with the exception of a few sanctuaries for gay political debate such as the local lesbian bar Charlene’s, run by the activist Charlene Schneider.

By 1988, the 15th anniversary of the fire, the UpStairs Lounge narrative comprised little more than a call for better fire codes and indoor sprinklers. UpStairs Lounge survivor Stewart Butler summed it up: “A tragedy that, as far as I know, no good came of.”

Finally, in 1991, at Stewart Butler and Charlene Schneider’s nudging, the UpStairs Lounge story became aligned with the crusade of liberated gays and lesbians seeking equal rights in Louisiana. The halls of power responded with intermittent progress. The New Orleans City Council, horrified by the story but not yet ready to take its look in the mirror, enacted an anti-discrimination ordinance protecting gays and lesbians in housing, employment, and public accommodations that Dec. 12 — more than 18 years after the fire.

“I believe the fire was the catalyst for the anger to bring us all to the table,” Schneider told The Times-Picayune, a tacit rebuke to Esteve’s strategy of silent accommodation. Even Esteve seemed to change his stance with time, granting a full interview with the first UpStairs Lounge scholar Johnny Townsend sometime around 1989.

Most of the figures in this historic tale are now deceased. What’s left is an enduring story that refused to go gently. The story now echoes around the world — a musical about the UpStairs Lounge fire recently played in Tokyo, translating the gay underworld of the 1973 French Quarter for Japanese audiences.

When I finished my presentation to the City Council last June, I looked up to see the seven council members in tears. Unanimously, they approved a resolution acknowledging the historic failures of city leaders in the wake of the UpStairs Lounge fire.

Council members personally apologized to UpStairs Lounge families and survivors seated in the chamber in a symbolic act that, though it could not bring back those who died, still mattered greatly to those whose pain had been denied, leaving them to grieve alone. At long last, official silence and indifference gave way to heartfelt words of healing.

The way Americans remember the past is an active, ongoing process. Our collective memory is malleable, but it matters because it speaks volumes about our maturity as a people, how we acknowledge the past’s influence in our lives, and how it shapes the examples we set for our youth. Do we grapple with difficult truths, or do we duck accountability by defaulting to nostalgia and bluster? Or worse, do we simply ignore the past until it fades into a black hole of ignorance and indifference?

I believe that a factual retelling of the UpStairs Lounge tragedy — and how, 50 years onward, it became known internationally — resonates beyond our current divides. It reminds queer and non-queer Americans that ignoring the past holds back the present, and that silence is no cure for what ails a participatory nation.

Silence isolates. Silence gaslights and shrouds. It preserves the power structures that scapegoat the disempowered.

Solidarity, on the other hand, unites. Solidarity illuminates a path forward together. Above all, solidarity transforms the downtrodden into a resounding chorus of citizens — in the spirit of voices who once gathered ‘round a white baby grand piano and sang, joyfully and loudly, “United We Stand.”

Robert W. Fieseler is a New Orleans-based journalist and the author of “Tinderbox: the Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation.”

homepage news

New Supreme Court term includes critical LGBTQ case with ‘terrifying’ consequences

Business owner seeks to decline services for same-sex weddings

The U.S. Supreme Court, after a decision overturning Roe v. Wade that still leaves many reeling, is starting a new term with justices slated to revisit the issue of LGBTQ rights.

In 303 Creative v. Elenis, the court will return to the issue of whether or not providers of custom-made goods can refuse service to LGBTQ customers on First Amendment grounds. In this case, the business owner is Lorie Smith, a website designer in Colorado who wants to opt out of providing her graphic design services for same-sex weddings despite the civil rights law in her state.

Jennifer Pizer, acting chief legal officer of Lambda Legal, said in an interview with the Blade, “it’s not too much to say an immeasurably huge amount is at stake” for LGBTQ people depending on the outcome of the case.

“This contrived idea that making custom goods, or offering a custom service, somehow tacitly conveys an endorsement of the person — if that were to be accepted, that would be a profound change in the law,” Pizer said. “And the stakes are very high because there are no practical, obvious, principled ways to limit that kind of an exception, and if the law isn’t clear in this regard, then the people who are at risk of experiencing discrimination have no security, no effective protection by having a non-discrimination laws, because at any moment, as one makes their way through the commercial marketplace, you don’t know whether a particular business person is going to refuse to serve you.”

The upcoming arguments and decision in the 303 Creative case mark a return to LGBTQ rights for the Supreme Court, which had no lawsuit to directly address the issue in its previous term, although many argued the Dobbs decision put LGBTQ rights in peril and threatened access to abortion for LGBTQ people.

And yet, the 303 Creative case is similar to other cases the Supreme Court has previously heard on the providers of services seeking the right to deny services based on First Amendment grounds, such as Masterpiece Cakeshop and Fulton v. City of Philadelphia. In both of those cases, however, the court issued narrow rulings on the facts of litigation, declining to issue sweeping rulings either upholding non-discrimination principles or First Amendment exemptions.

Pizer, who signed one of the friend-of-the-court briefs in opposition to 303 Creative, said the case is “similar in the goals” of the Masterpiece Cakeshop litigation on the basis they both seek exemptions to the same non-discrimination law that governs their business, the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act, or CADA, and seek “to further the social and political argument that they should be free to refuse same-sex couples or LGBTQ people in particular.”

“So there’s the legal goal, and it connects to the social and political goals and in that sense, it’s the same as Masterpiece,” Pizer said. “And so there are multiple problems with it again, as a legal matter, but also as a social matter, because as with the religion argument, it flows from the idea that having something to do with us is endorsing us.”

One difference: the Masterpiece Cakeshop litigation stemmed from an act of refusal of service after owner, Jack Phillips, declined to make a custom-made wedding cake for a same-sex couple for their upcoming wedding. No act of discrimination in the past, however, is present in the 303 Creative case. The owner seeks to put on her website a disclaimer she won’t provide services for same-sex weddings, signaling an intent to discriminate against same-sex couples rather than having done so.

As such, expect issues of standing — whether or not either party is personally aggrieved and able bring to a lawsuit — to be hashed out in arguments as well as whether the litigation is ripe for review as justices consider the case. It’s not hard to see U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts, who has sought to lead the court to reach less sweeping decisions (sometimes successfully, and sometimes in the Dobbs case not successfully) to push for a decision along these lines.

Another key difference: The 303 Creative case hinges on the argument of freedom of speech as opposed to the two-fold argument of freedom of speech and freedom of religious exercise in the Masterpiece Cakeshop litigation. Although 303 Creative requested in its petition to the Supreme Court review of both issues of speech and religion, justices elected only to take up the issue of free speech in granting a writ of certiorari (or agreement to take up a case). Justices also declined to accept another question in the petition request of review of the 1990 precedent in Smith v. Employment Division, which concluded states can enforce neutral generally applicable laws on citizens with religious objections without violating the First Amendment.

Representing 303 Creative in the lawsuit is Alliance Defending Freedom, a law firm that has sought to undermine civil rights laws for LGBTQ people with litigation seeking exemptions based on the First Amendment, such as the Masterpiece Cakeshop case.

Kristen Waggoner, president of Alliance Defending Freedom, wrote in a Sept. 12 legal brief signed by her and other attorneys that a decision in favor of 303 Creative boils down to a clear-cut violation of the First Amendment.

“Colorado and the United States still contend that CADA only regulates sales transactions,” the brief says. “But their cases do not apply because they involve non-expressive activities: selling BBQ, firing employees, restricting school attendance, limiting club memberships, and providing room access. Colorado’s own cases agree that the government may not use public-accommodation laws to affect a commercial actor’s speech.”

Pizer, however, pushed back strongly on the idea a decision in favor of 303 Creative would be as focused as Alliance Defending Freedom purports it would be, arguing it could open the door to widespread discrimination against LGBTQ people.

“One way to put it is art tends to be in the eye of the beholder,” Pizer said. “Is something of a craft, or is it art? I feel like I’m channeling Lily Tomlin. Remember ‘soup and art’? We have had an understanding that whether something is beautiful or not is not the determining factor about whether something is protected as artistic expression. There’s a legal test that recognizes if this is speech, whose speech is it, whose message is it? Would anyone who was hearing the speech or seeing the message understand it to be the message of the customer or of the merchants or craftsmen or business person?”

Despite the implications in the case for LGBTQ rights, 303 Creative may have supporters among LGBTQ people who consider themselves proponents of free speech.

One joint friend-of-the-court brief before the Supreme Court, written by Dale Carpenter, a law professor at Southern Methodist University who’s written in favor of LGBTQ rights, and Eugene Volokh, a First Amendment legal scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles, argues the case is an opportunity to affirm the First Amendment applies to goods and services that are uniquely expressive.

“Distinguishing expressive from non-expressive products in some contexts might be hard, but the Tenth Circuit agreed that Smith’s product does not present a hard case,” the brief says. “Yet that court (and Colorado) declined to recognize any exemption for products constituting speech. The Tenth Circuit has effectively recognized a state interest in subjecting the creation of speech itself to antidiscrimination laws.”

Oral arguments in the case aren’t yet set, but may be announced soon. Set to defend the state of Colorado and enforcement of its non-discrimination law in the case is Colorado Solicitor General Eric Reuel Olson. Just this week, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would grant the request to the U.S. solicitor general to present arguments before the justices on behalf of the Biden administration.

With a 6-3 conservative majority on the court that has recently scrapped the super-precedent guaranteeing the right to abortion, supporters of LGBTQ rights may think the outcome of the case is all but lost, especially amid widespread fears same-sex marriage would be next on the chopping block. After the U.S. Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against 303 Creative in the lawsuit, the simple action by the Supreme Court to grant review in the lawsuit suggests they are primed to issue a reversal and rule in favor of the company.

Pizer, acknowledging the call to action issued by LGBTQ groups in the aftermath of the Dobbs decision, conceded the current Supreme Court issuing the ruling in this case is “a terrifying prospect,” but cautioned the issue isn’t so much the makeup of the court but whether or not justices will continue down the path of abolishing case law.

“I think the question that we’re facing with respect to all of the cases or at least many of the cases that are in front of the court right now, is whether this court is going to continue on this radical sort of wrecking ball to the edifice of settled law and seemingly a goal of setting up whole new structures of what our basic legal principles are going to be. Are we going to have another term of that?” Pizer said. “And if so, that’s terrifying.”

homepage news

Kelley Robinson, a Black, queer woman, named president of Human Rights Campaign

Progressive activist a veteran of Planned Parenthood Action Fund

Kelley Robinson, a Black, queer woman and veteran of Planned Parenthood Action Fund, is to become the next president of the Human Rights Campaign, the nation’s leading LGBTQ group announced on Tuesday.

Robinson is set to become the ninth president of the Human Rights Campaign after having served as executive director of Planned Parenthood Action Fund and more than 12 years of experience as a leader in the progressive movement. She’ll be the first Black, queer woman to serve in that role.

“I’m honored and ready to lead HRC — and our more than three million member-advocates — as we continue working to achieve equality and liberation for all Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer people,” Robinson said. “This is a pivotal moment in our movement for equality for LGBTQ+ people. We, particularly our trans and BIPOC communities, are quite literally in the fight for our lives and facing unprecedented threats that seek to destroy us.”

The next Human Rights Campaign president is named as Democrats are performing well in polls in the mid-term elections after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, leaving an opening for the LGBTQ group to play a key role amid fears LGBTQ rights are next on the chopping block.

“The overturning of Roe v. Wade reminds us we are just one Supreme Court decision away from losing fundamental freedoms including the freedom to marry, voting rights, and privacy,” Robinson said. “We are facing a generational opportunity to rise to these challenges and create real, sustainable change. I believe that working together this change is possible right now. This next chapter of the Human Rights Campaign is about getting to freedom and liberation without any exceptions — and today I am making a promise and commitment to carry this work forward.”

The Human Rights Campaign announces its next president after a nearly year-long search process after the board of directors terminated its former president Alphonso David when he was ensnared in the sexual misconduct scandal that led former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo to resign. David has denied wrongdoing and filed a lawsuit against the LGBTQ group alleging racial discrimination.

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoCatching up with the asexuals and aromantics of D.C.

-

South America4 days ago

South America4 days agoArgentina government dismisses transgender public sector employees

-

Maine5 days ago

Maine5 days agoMaine governor signs transgender, abortion sanctuary bill into law

-

Mexico3 days ago

Mexico3 days agoMexican Senate approves bill to ban conversion therapy