Arts & Entertainment

Roadwork reflects on its herstory to plan its future

Social justice coalition makes room for the next generation of artist activists

In 1978, amid the second wave of feminism in the aftermath of Roe v. Wade, Roadwork – a multiracial coalition – put women’s art, particularly that of women of color, on the road. Building the roads where they didn’t already exist, Roadwork created an intersection of opportunity and social change, wherein artists from diverse backgrounds shared their voices while advancing an array of social justice movements.

Forty-five years later, the coalition remains firm in its vision to support artists while connecting them to women’s cultural contributions that are absent from white feminist history. However, today, the organization is reflecting on women’s history more than ever to gauge how Roadwork will best support women and queer artists in the future.

“The beautiful thing about movements over time is that we keep growing and learning,” Roadwork co-founder Amy Horowitz said. “[For] Roadwork, it’s like a dream come true that younger artists activists are envisioning a new way forward.”

Horowitz and Bernice Johnson Reagon founded Roadwork when the very word “woman” was radicalized, Horowitz said. As activists in their 20s and early 30s, Horowitz and Reagon developed the organization as they went along, producing shows while supporting civil rights, women’s rights and gay rights movements in Washington, D.C.

In addressing how racist or misogynistic ideologies exist not only systemically but also within individuals and women’s movements, Roadwork created events where activists could focus on building coalitions across differences to take a congregational approach to fight regressive social forces like racism, sexism, and homophobia.

One manifestation of this vision was the Sisterfire Festival. Started in 1982 as a one-day fundraising festival to amplify the work of grassroots artists in response to arts funding cuts, the event welcomed all genders, races, and sexualities to support women’s voices. The festival then evolved into an annual celebration that required year-round booking, production, and coalition building.

“Sisterfire does not exist in a vacuum, it is in the voice of the song, it is in the pictures we draw, it is in the leap of the dance, and it is in the shout of the poem that we send forth, beyond the battle, our vision of the way the world should be,” a host of the first Sisterfire Festival said on stage.

The Sisterfire Festival ran until 1989, two years after two white lesbian separatists refused to let two gay Black Sisterfire volunteers into their booth during the festival.

“The festival went on for a few years after that, but we, at that point, couldn’t recover from that attack that we received from the radical lesbian separatist movement,” Horowitz said.

But the end of the Sisterfire Festival didn’t overshadow Roadwork’s vision. Horowitz founded the Jerusalem Project in 1991 with the help of the Smithsonian Institution for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, strengthening what is now a longstanding relationship between Roadwork and the Smithsonian Institute.

Roadwork even collaborated with the Smithsonian Folklife Festival and the Kennedy Center Millennium Stage in 2018 for the coalition’s 40th-anniversary celebration – a Sisterfire reunion festival.

After packing an audience into the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage, the Kennedy Center invited Roadwork back for a Sisterfire showcase every year since the reunion.

“It just really seemed like an awesome thing to do, to localize that, kind of, official space and grassrootsify it,” Horowitz said. “They support us doing what we want to do.”

As Roadwork prepared for this year’s annual Sisterfire showcase on March 4, the coalition takes time to reflect on where they’ve been to find direction in where to move forward, according to Roadwork Interim Director Lehuanani DeFranco.

During Sisterfire’s hiatus, Roadwork prioritized gathering archival information. After a storage facility sold and emptied one of Roadwork’s storage units that held archives, the challenge to recover the past came with a time limit.

“In this day and age where people are getting older and the stories are sort of getting lost, it’s really important to be able to collect any of that information, whether from the different types of programs or letters that would come in, to videos and archival footage that we’d be taking from interviews with people,” DeFranco said.

Collecting the oral and documented histories of Roadwork holds the coalition accountable as community builders reacting to change, DeFranco added. Aside from looking back to see how Roadwork previously dealt with challenges or considering how the coalition needs to evolve, collecting archives may also enable Roadwork to share these diverse historical perspectives with museums and universities for the next generation.

Beyond connecting the next generation of artists activists to this history, the coalition is entrusting the next generation of Roadwork leaders with finding the communities and organizations that need support in their fight for social change.

“I’m really wanting to hand over the reins, in a way, of the type of artists that we are putting on stage and the type of artists that others think should be elevated in their community,” DeFranco said.

Supporting artists also means granting them the freedom and trust to share their art in the way they want. While Roadwork offers its resources and connections to advance other projects, its fiscal sponsorship doesn’t change the vision of the project and instead operates as more of a “big sister relationship,” DeFranco explained.

Roadwork currently is involved in nine projects, including three educational initiatives, three documentary projects and three sponsored projects supporting archival work, artist housing, and Indigenous music curation aimed at reimagining Western music genres.

Team DC, the umbrella organization for LGBTQ-friendly sports teams and leagues in the D.C. area, held its annual Night of Champions Awards Gala on Saturday, April 20 at the Hilton National Mall. The organization gave out scholarships to area LGBTQ student athletes as well as awards to the Different Drummers, Kelly Laczko of Duplex Diner, Stacy Smith of the Edmund Burke School, Bryan Frank of Triout, JC Adams of DCG Basketball and the DC Gay Flag Football League.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

The 2024 National Cannabis Festival was held at the Fields at RFK Stadium on April 19-20.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

Covering the @NatlCannaFest at RFK Stadium for @WashBlade . Stop by the LGBTQ+ booth and pick up a paper if you are here. pic.twitter.com/is7hnsaPns

— Michael Patrick Key (@MichaelKeyWB) April 20, 2024

Theater

‘Amm(i)gone’ explores family, queerness, and faith

A ‘fully autobiographical’ work from out artist Adil Mansoor

‘Amm(i)gone’

Thorough May 12

Woolly Mammoth Theatre

641 D St., N.W.

$60-$70

Woollymammoth.net

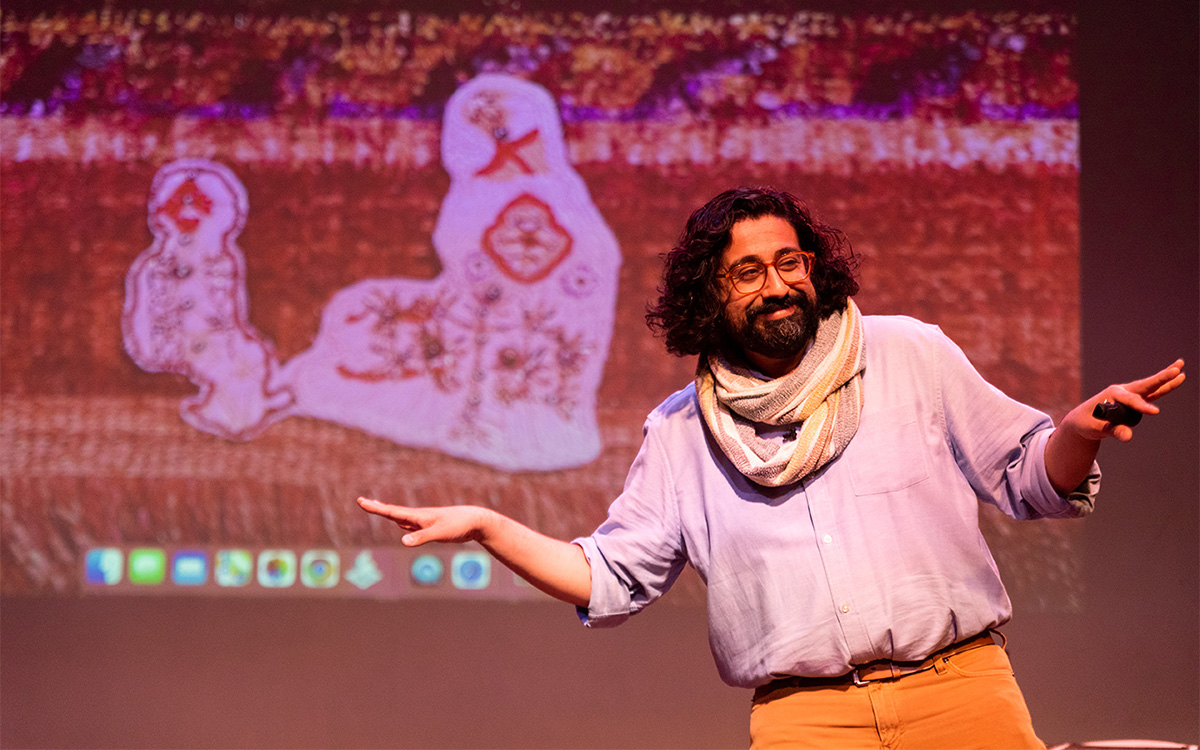

“Fully and utterly autobiographical.” That’s how Adil Mansoor describes “Amm(i)gone,” his one-man work currently playing at Woolly Mammoth Theatre.

Both created and performed by out artist Mansoor, it’s his story about inviting his Pakistani mother to translate Sophocles’s Greek tragedy “Antigone” into Urdu. Throughout the journey, there’s an exploration of family, queerness, and faith,as well as references to teachings from the Quran, and audio conversations with his Muslim mother.

Mansoor, 38, grew up in the suburbs of Chicago and is now based in Pittsburgh where he’s a busy theater maker. He’s also the founding member of Pittsburgh’s Hatch Arts Collective and the former artistic director of Dreams of Hope, an LGBTQ youth arts organization.

WASHINGTON BLADE: What spurred you to create “Amm(i)gone”?

ADIL MANSOOR: I was reading a translation of “Antigone” a few years back and found myself emotionally overwhelmed. A Theban princess buries her brother knowing it will cost her, her own life. It’s about a person for whom all aspirations are in the afterlife. And what does that do to the living when all of your hopes and dreams have to be reserved for the afterlife?

I found grant funding to pay my mom to do the translation. I wanted to engage in learning. I wanted to share theater but especially this ancient tragedy. My mother appreciated the characters were struggling between loving one another and their beliefs.

BLADE: Are you more director than actor?

MANSOOR: I’m primarily a director with an MFA in directing from Carnegie Mellon. I wrote, directed, and performed in this show, and had been working on it for four years. I’ve done different versions including Zoom. Woolly’s is a new production with the same team who’ve been involved since the beginning.

I love solo performance. I’ve produced and now teach solo performance and believe in its power. And I definitely lean toward “performance” and I haven’t “acted” since I was in college. I feel good on stage. I was a tour guide and do a lot of public speaking. I enjoy the attention.

BLADE: Describe your mom.

MANSOOR: My mom is a wonderfully devout Muslim, single mother, social worker who discovered my queerness on Google. And she prays for me.

She and I are similar, the way we look at things, the way we laugh. But different too. And those are among the questions I ask in this show. Our relationship is both beautiful and complicated.

BLADE: So, you weren’t exactly hiding your sexuality?

MANSOOR: In my mid-20s, I took time to talk with friends about our being queer with relation to our careers. My sexuality is essential to the work. As the artistic director at Dreams of Hope, part of the work was to model what it means to be public. If I’m in a room with queer and trans teenagers, part of what I’m doing is modeling queer adulthood. The way they see me in the world is part of what I’m putting out there. And I want that to be expansive and full.

So much of my work involves fundraising and being a face in schools. Being out is about making safe space for queer young folks.

BLADE: Have you encountered much Islamophobia?

MANSOOR: When 9/11 happened, I was a sophomore in high school, so yes. I faced a lot then and now. I’ve been egged on the street in the last four months. I see it in the classroom. It shows up in all sorts of ways.

BLADE: What prompted you to lead your creative life in Pittsburgh?

MANSOOR: I’ve been here for 14 years. I breathe with ease in Pittsburgh. The hills and the valleys and the rust of the city do something to me. It’s beautiful, it’ affordable, and there is support for local artists. There’s a lot of opportunity.

Still, the plan was to move to New York in September of 2020 but that was cancelled. Then the pandemic showed me that I could live in Pittsburgh and still have a nationally viable career.

BLADE: What are you trying to achieve with “Amm(i)gone”?

MANSOOR: What I’m sharing in the show is so very specific but I hear people from other backgrounds say I totally see my mom in that. My partner is Catholic and we share so much in relation to this.

I hope the work is embracing the fullness of queerness and how means so many things. And I hope the show makes audiences want to call their parents or squeeze their partners.

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoNew D.C. LGBTQ+ bar Crush set to open April 19

-

District of Columbia5 days ago

District of Columbia5 days agoReenactment of first gay rights picket at White House draws interest of tourists

-

Arizona5 days ago

Arizona5 days agoAriz. governor vetoes anti-transgender, Ten Commandments bill

-

South America3 days ago

South America3 days agoDaniel Zamudio murderer’s parole request denied