Books

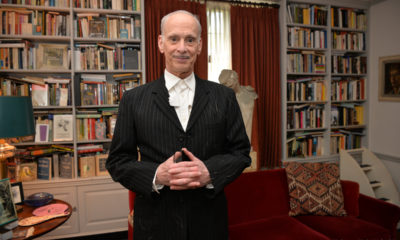

John Waters talks about his debut novel, ‘Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance’

Nationwide book tour kicks off in D.C.

John Waters has directed movies; written non-fiction; given spoken-word performances; made visual art; modeled for fashion designers, even lent his voice to a country music video. After reaching his 70s, he added a new occupation: Novelist.

The result, after three years of writing, is “Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance,” published last month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. It follows Marsha Sprinkle, a woman who steals suitcases at the airport; her mother Adora, who performs plastic surgery on pets; Marsha’s daughter Poppy, the head of a band of renegade trampoline bouncers; Marsha’s partner-in-crime, Daryl, and Daryl’s talking penis, Richard.

Set in Baltimore and points north, Liarmouth is what fans of John Waters might expect from him and yet different from anything he’s done before. As the title implies, it’s filled with stories and situations that seem hard to believe but may be just a few years away from happening, such as facelifts on pets. It also gives Waters a chance to write about sexual kinks including erotic tickling and ear masturbation.

To promote his debut novel, Waters, 76, launched a coast-to-coast book tour that began in Washington, D.C. at Politics and Prose Bookstore, where he was interviewed by Baltimore-based writer and columnist Marion Winik. The following transcript of their conversation has been condensed and edited.

Marion Winik: John, this is your debut novel, and the convention is that a debut novel is usually highly autographical, a version of the author’s coming of age. Is this true of Liarmouth?

John Waters: No. I think I am every character in it. When you write a novel, you live with those people. You become those people. I read it aloud to make sure I don’t say the same word over and over and everything.

Q: Is there one character you identify with more than the others?

A: Well, Marsha, only because I love to have villains that are the heroines in my book. I think Marsha Sprinkle would get along with Francine Fishpaw. She would get along with Serial Mom. She would get along with all of them. But she’s a loathsome person. She does terrible things. She loves to lie. Lying gives her power. It makes her feel prettier. She does even practice lies. You know, just to get in shape, like going to the gym. She’s a contemptible person, really. She only eats crackers because she never wants to defecate. She finds that repellent. She just shoots out little pellets. She doesn’t have to wipe, even.

Q:This leads to my next question. I picture a book group, for example, the book club at the Baltimore Museum of Art, which is mostly ladies from Guilford, discussing this book. And I picture them asking the question: Is poop really this funny?

A: Well, she learns to have a proper bowel movement, later, through love. She has a fudge dragon. That’s one that won’t even flush. You asked me. But anyway, this is a tiny portion of the book.

Q: Not too tiny.

A: And Anne Tyler read this book. That was my favorite. Anne’s my friend and I said to her, “Oh, you poor thing. You have to read this book.”

Q: In comparing your films to this novel, I realized that you’re in fact a magical realist much like Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Isabel Allende. And while I suppose CGI [computer generated imagery] could create a film equivalent for Richard the Talking Penis, I would argue that Richard has a life on the page that he could not have in film. Do you agree? Did you find that you could do things in fiction that you can’t do in any other medium?

A: Certainly you can. Because I don’t have to worry about the budget. If this were a movie, it would be NC-17, which would make it not get made, and it would also have a huge special effects budget, because there’s all this insane trampolining going on and bouncing and everything, and Daryl does have a talking penis. Now, there are talking penises in a lot of books. But in mine, his penis turns gay while he’s straight and it’s a battle. So could that become a movie? Sure. But somebody has to buy the rights from me to make it. That’s even funnier.

Q: Maybe Pixar. Going into the fudge dragon situation.

A: I thought I was trying to get away from that.

Q: The entire group of people is heading up to Provincetown for something called The Analingus Festival.

A: She’s giving the plot away. But it’s not so hard to imagine that in Provincetown they would have an Analingus Festival. They have Gay Pilots’ Week. They have Lesbian Crafts Week. They have Gay Family Week. They have Bear Week.They have every kind of obscure thing. So Analingus Week, maybe this book will make that happen. They could have children with face-painting, like, anuses, and Rimmer Bingo. Make it a real theme.

Q: Back to trampolines: Marsha has a daughter that’s alienated from her and has gotten involved with a movement. It’s kind of an identity, sort of like LGBTQIA+, but this one is trampolines.

A: She’s been shut down, from a trampoline accident at her Bouncy-Bouncy place.

Q: In the book, ‘trampoline’ is standing in for many, many different identities. It gets to be the occasion to make many, many woke jokes, but the woke jokes are all about trampolines.

A: They have to bounce. Their car bounces when they’re in airports. They live on waterbeds so they can bounce. They only eat food that bounces.

Q: Where did this come from? Why trampolines?

A: I don’t know. I just thought of it. I read about trampoline parks and then I went to one. I know they get shut down because of accidents and stuff, so I tried to imagine a cult where it was like a speakeasy where she opens illegally, and these [trampoline people] — they call them Tramps – hang out and there are other Tramps and they see each other around. There are all these people that are going like this all the time and they can’t keep still, or they get depressed. So they keep bouncing more and more and they get higher and then they learn to do other things, like shake sideways and roll and all different spiritual things.

But once they learn these powers, they realize that there are drawbacks. There are side effects. So I believe, in a novel, once you set up this world, no matter how crazy it is, there are rules in that world and you have to respect it, no matter how crazy it is. So even if there’s something that’s completely impossible to happen, as long as the logic of the novel that you set up follows it, it’s like having a continuity person in a movie. Copy editors do that. They go through with you and they say, ‘Well, how could this be?’ It doesn’t matter how could it be. Nobody jumps up in the air and stays up there. But still, if you believe in that happening, then there’s a certain logic that has to continue through the whole thing. Now, this book, I make fun of narrative. Like, 40 things happen in every sentence. If in four days, all this happened to any one person, they would be dead from exhaustion.

Q: But then they’d be at the Analingus Festival, so everything would be great. Back in the 1970s, Abbie Hoffman wrote Steal This Book and taught thousands of people how to make free long-distance phone calls and wring a profit from American Express travelers checks.

A: I did both of those things. You’d buy $500 worth of travelers checks. Your friend would go. They’d look the same. He’d report them stolen and I’d report them, and then we’d split it. You could cash them. One cashes the other’s.

Q: Aren’t you worried that your book is going to spawn a lookalike baggage claim theft [wave]?

A: Well, it is easy. To me, the security in airports after 9-11, it completely changed where you couldn’t do anything. Except the one thing they did was stop checking luggage tags. They used to [check tags], in every airport when you came in. Now they don’t. And it gave me the idea because I was with my friend Pat Moran once and we were leaving the airport and this man was chasing us up the escalator: “You’ve got my bag!” They do all look alike. So even if you get caught, you can say, “Oh, I’m sorry, I thought [it was mine].” And [Marsha] has a fake chauffeur with her so it even looks more real.

And there’s another thing. I know somebody that steals flight attendants’ pocketbooks when they get on a plane, because they’re always in the same place. So I do tell that. And my friend, when she did it, her friend was with her and she didn’t know and then they said, “All right. Someone took the flight attendant’s pocketbook. No one’s getting off this plane.” Like school. And she didn’t snitch, and the plane eventually took off. So I’ve heard of some of these things, but I exaggerated. I’m in a plane almost every day, touring with my shows and everything. So I’m doing research the whole time — how women always put their pocketbook in first and how you can get things when they come out of the X-ray.

An easy way to steal — the Baltimore airport has not done anything about this, but in the [bathroom] stalls, always, the hook for your coat, people reach right over and grab your bag and run. So, many airports have lowered it. Baltimore has not yet. You can still do that. When someone’s on the toilet, they just reach over and grab your coat or your bag when it’s on the hook. You’d have to pull your pants up to chase them. They’re out of there.

Q: You have to do a book-signing at BWI [airport.] As far as social commentary goes in this book, there’s plenty. It’s not just the trampolines. There’s Marsha’s mother. Tell us a little about Marsha’s mother.

A: Her mother does facelifts on pets, illegally. Then the dog has a problem and thinks he’s a cat. So he’s trapped in a cat’s body. It like species change.

Q: He’s transitioning.\

A: It’s complicated. It is. But I don’t think animal plastic surgery is too far in the future. I can imagine it in Beverly Hills, I really can, where they try to get the cat to look like Joan Rivers, that wind tunnel look. But [Adora] has her own plastic surgery. She makes her belly button an outie, not an innie, because she’s repelled by nature catching things in her. She’s obsessed by nature’s garbage can, her belly button.

Q: I feel like the whole country is full of people who can’t make a joke about anything. I mean, God forbid we would talk about a dog who wants to transition to being a cat, or the people with the trampoline not being able to express their identity. I am wondering, how are you getting to make these jokes?

A: Well, because I don’t think they’re mean. I make fun of the rules in my own community that I live in, the community I love. I’m a bleeding-heart liberal. I say I’m an Antifa sympathizer who’s too old to run from the tear gas. But we made fun of ourselves, with Abbie Hoffman and that crowd. That’s the only thing the trigger-warning crowd doesn’t [do.] They don’t make fun of themselves, and they need to a little, you know? So I’m making fun of something I love, but I don’t think I’m mean-spirited.

I did a show this week and the first question that really threw me was: How did you avoid cancer? I quit smoking. But what they really said was: How did you avoid getting cancelled?… If I fear censorship today, it would not be from the right. It would be from maybe the left. A rich kid in school. I agree with what they’re saying. I just don’t agree with the self-righteousness about it. Make fun of yourself. I made fun of everything. Johnny Depp made of himself. That’s why he was in Cry-Baby. Patty Hearst made fun of being a victim by being in a movie. Traci Lords made fun of being in porn by playing a bad girl. If you make fun of what you’re trying to do, then you can work, because humor is what works. Humor is what gets people to listen, not standing up and badgering, saying you can’t do this.

Q: I think you are cancel-proof.

A: No, I don’t think I am. And I think you have to be very careful. There is now a sensitivity editor, a word I can barely say out loud, [in publishing.] My friend Bruce Wagner’s whole book stopped because of sensitivity editors. They go through the book. We sent [Liarmouth] to a sensitivity editor and they refused to call back. Even my editor didn’t know what to do with that, so we just went on. I did read through it with my editor, my agent, and I have three really smart women who work for me who are three generations and are really good copy editors and we went through it. And if anything was touchy today, we went even further liberal the other way to make it funnier.

Q: What’s an example of that?

A: Well, in the first part, there’s this bus accident and this one couple is trapped in their seats but they were Asians. Which was fine, but then during [the writing], there was Asian violence, so we can’t have that. Marsha is proud that all of her victims are diverse. And whenever I introduce a character, I say ‘a white man,’ because I read once that all writers, if someone is white they never say that but if it’s a black person, the first time it comes up they say ‘a black person.’ So I try to put, if it’s a white person, I say that. I get that race is the most touchy thing. But I wanted to have every race in the book. The Asian couple we changed to Italian American and that wasn’t offensive. Why? Because it’s the news. So I tried to make fun of that but embracing it by trying to be even overly politically correct while making fun of it.

Q: I think it’s inspiring and leading the way, to show that we can still laugh about these things and there still can be jokes about them.

A: Racism isn’t funny. I say that in my [spoken word] show, that basically Black Lives Matter is the most effective [movement] since Martin Luther King. But I wish Jet magazine, which I used to get and love, would come back and have it be a hip kind of magazine for [black readers[ that makes fun of white reaction to it. This black friend in Baltimore told me that a guy at work said to her, what’s your tracking number, your bank? She said, “For what?” He said, “I want to send you something.” He sent her $50. She said, “What’s this for?” He said, “You know.” Slavery? No wonder there’s rage out there. Fifty bucks? Like that’s going to make up for it. I thought thatJet magazine could be like Spy magazine, only to make fun of white liberals’ reactions to Black Lives Matter.

Q: That’s a really good idea. Are you going to write another novel?

A: I hope so…The reviews so far have been good. But I don’t know yet…The best thing that could happen to this book is if the Florida governor bans it.

Question from the audience: Why a novel now, at 76?

A: Well, it’s not that big a stretch because I’ve written15 movies. They’re fiction. In Carsick, the book where I hitchhiked across the country, the first two thirds of the book I made up as the worst rides I could get and the best, like in fiction. And then I wrote about the real way it happened. That was easy. I was in it. But [why now?] To do it. To challenge myself. The same reason I hitchhiked across the country at 66, why I took LSD when I was 70, for the first time in 50 years. Just to challenge myself. I don’t know. What am I going to do when I’m 80? Turn straight? That’d be a stunt. Old chickens make good soup.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Feminist fiction fans will love ‘Bog Queen’

A wonderful tale of druids, warriors, scheming kings, and a scientist

‘Bog Queen’

By Anna North

c.2025, Bloomsbury

$28.99/288 pages

Consider: lost and found.

The first one is miserable – whatever you need or want is gone, maybe for good. The second one can be joyful, a celebration of great relief and a reminder to look in the same spot next time you need that which you first lost. Loss hurts. But as in the new novel, “Bog Queen” by Anna North, discovery isn’t always without pain.

He’d always stuck to the story.

In 1961, or so he claimed, Isabel Navarro argued with her husband, as they had many times. At one point, she stalked out. Done. Gone, but there was always doubt – and now it seemed he’d been lying for decades: when peat cutters discovered the body of a young woman near his home in northwest England, Navarro finally admitted that he’d killed Isabel and dumped her corpse into a bog.

Officials prepared to charge him.

But again, that doubt. The body, as forensic anthropologist Agnes Lundstrom discovered rather quickly, was not that of Isabel. This bog woman had nearly healed wounds and her head showed old skull fractures. Her skin glowed yellow from decaying moss that her body had steeped in. No, the corpse in the bog was not from a half-century ago.

She was roughly 2,000 years old.

But who was the woman from the bog? Knowing more about her would’ve been a nice distraction for Agnes; she’d left America to move to England, left her father and a man she might have loved once, with the hope that her life could be different. She disliked solitude but she felt awkward around people, including the environmental activists, politicians, and others surrounding the discovery of the Iron Age corpse.

Was the woman beloved? Agnes could tell that she’d obviously been well cared-for, and relatively healthy despite the injuries she’d sustained. If there were any artifacts left in the bog, Agnes would have the answers she wanted. If only Isabel’s family, the activists, and authorities could come together and grant her more time.

Fortunately, that’s what you get inside “Bog Queen”: time, spanning from the Iron Age and the story of a young, inexperienced druid who’s hoping to forge ties with a southern kingdom; to 2018, the year in which the modern portion of this book is set.

Yes, you get both.

Yes, you’ll devour them.

Taking parts of a true story, author Anna North spins a wonderful tale of druids, vengeful warriors, scheming kings, and a scientist who’s as much of a genius as she is a nerd. The tale of the two women swings back and forth between chapters and eras, mixed with female strength and twenty-first century concerns. Even better, these perfectly mixed parts are occasionally joined by a third entity that adds a delicious note of darkness, as if whatever happens can be erased in a moment.

Nah, don’t even think about resisting.

If you’re a fan of feminist fiction, science, or novels featuring kings, druids, and Celtic history, don’t wait. “Bog Queen” is your book. Look. You’ll be glad you found it.

This past year, you’ve often had to make do.

Saving money here, resources there, being inventive and innovative. It’s a talent you’ve honed, but isn’t it time to have the best? Yep, so grab these Ten Best of 2025 books for your new year pleasures.

Nonfiction

Health care is on everyone’s mind now, and “A Living: Working-Class Americans Talk to Their Doctor” by Michael D. Stein, M.D. (Melville House, $26.99) lets you peek into health care from the point of view of a doctor who treats “front-line workers” and those who experience poverty and homelessness. It’s shocking, an eye-opening book, a skinny, quick-to-read one that needs to be read now.

If you’ve been doing eldercare or caring for any loved one, then “How to Lose Your Mother: A Daughter’s Memoir” by Molly Jong-Fast (Viking, $28) needs to be in your plans for the coming year. It’s a memoir, but also a biography of Jong-Fast’s mother, Erica Jong, and the story of love, illness, and living through the chaos of serious disease with humor and grace. You’ll like this book especially if you were a fan of the author’s late mother.

Another memoir you can’t miss this year is “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: A Veteran’s Memoir” by Khadijah Queen (Legacy Lit, $30.00). It’s the story of one woman’s determination to get out of poverty and get an education, and to keep her head above water while she goes below water by joining the U.S. Navy. This is a story that will keep you glued to your seat, all the way through.

Self-improvement is something you might think about tackling in the new year, and “Replaceable You: Adventures in Human Anatomy” by Mary Roach (W.W. Norton & Company, $28.99) is a lighthearted – yet real and informative – look at the things inside and outside your body that can be replaced or changed. New nose job? Transplant, new dental work? Learn how you can become the Bionic Person in real life, and laugh while you’re doing it.

The science lover inside you will want to read “The Grave Robber: The Biggest Stolen Artifacts Case in FBI History and the Bureau’s Quest to Set Things Right” by Tim Carpenter (Harper Horizon, $29.99). A history lover will also want it, as will anyone with a craving for true crime, memoir, FBI procedural books, and travel books. It’s the story of a man who spent his life stealing objects from graves around the world, and an FBI agent’s obsession with securing the objects and returning them. It’s a fascinating read, with just a little bit of gruesome thrown in for fun.

Fiction

Speaking of a little bit of scariness, “Don’t Forget Me, Little Bessie” by James Lee Burke (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28) is the story of a girl named Bessie and her involvement with a cloven-hooved being who dogs her all her life. Set in still-wild south Texas, it’s a little bit western, part paranormal, and completely full of enjoyment.

“Evensong” by Stewart O’Nan (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28) is a layered novel of women’s friendships as they age together and support one another. The characters are warm and funny, there are a few times when your heart will sit in your throat, and you won’t be sorry you read it. It’s just plain irresistible.

If you need a dark tale for what’s left of a dark winter season, then “One of Us” by Dan Chaon (Henry Holt, $28), it it. It’s the story of twins who become orphaned when their Mama dies, ending up with a man who owns a traveling freak show, and who promises to care for them. But they can’t ever forget that a nefarious con man is looking for them; those kids can talk to one another without saying a word, and he’s going to make lots of money off them. This is a sharp, clever novel that fans of the “circus” genre shouldn’t miss.

“When the Harvest Comes” by Denne Michele Norris (Random House, $28) is a wonderful romance, a boy-meets-boy with a little spice and a lot of strife. Davis loves Everett but as their wedding day draws near, doubts begin to creep in. There’s homophobia on both sides of their families, and no small amount of racism. Beware that there’s some light explicitness in this book, but if you love a good love story, you’ll love this.

Another layered tale you’ll enjoy is “The Elements” by John Boyne (Henry Holt, $29.99), a twisty bunch of short stories that connect in a series of arcs that begin on an island near Dublin. It’s about love, death, revenge, and horror, a little like The Twilight Zone, but without the paranormal. You won’t want to put down, so be warned.

If you need more ideas, head to your local library or bookstore and ask the staff there for their favorite reads of 2025. They’ll fill your book bag and your new year with goodness.

Season’s readings!

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

This gay author sees dead people

‘Are You There Spirit? It’s Me, Travis’

By Travis Holp

c.2025, Spiegel and Grau

$28/240 pages

Your dad sent you a penny the other day, minted in his birth year.

They say pennies from heaven are a sign of some sort, and that makes sense: You’ve been thinking about him a lot lately. Some might scoff, but the idea that a lost loved one is trying to tell you he’s OK is comforting. So read the new book, “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis” by Travis Holp, and keep your eyes open.

Ever since he was a young boy growing up just outside Dayton, Ohio, Travis Holp wanted to be a writer. He also wanted to say that he was gay but his conservative parents believed his gayness was some sort of phase. That, and bullying made him hide who he was.

He also had to hide his nascent ability to communicate with people who had died, through an entity he calls “Spirit.” Eventually, though it left him with psychological scars and a drinking problem he’s since overcome, Holp was finally able to talk about his gayness and reveal his otherworldly ability.

Getting some people to believe that he speaks to the dead is still a tall order. Spirit helps naysayers, as well as Holp himself.

Spirit, he says, isn’t a person or an essence; Spirit is love. Spirit is a conduit of healing and energy, speaking through Holp in symbolic messages, feelings, and through synchronistic events. For example, Holp says coincidences are not coincidental; they’re ways for loved ones to convey messages of healing and energy.

To tap into your own healing Spirit, Holp says to trust yourself when you think you’ve received a healing message. Ignore your ego, but listen to your inner voice. Remember that Spirit won’t work on any fixed timeline, and its only purpose is to exist.

And keep in mind that “anything is possible because you are an unlimited being.”

You’re going to want very much to like “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis.” The cover photo of author Travis Holp will make you smile. Alas, what you’ll find in here is hard to read, not due to content but for lack of focus.

What’s inside this book is scattered and repetitious. Love, energy, healing, faith, and fear are words that are used often – so often, in fact, that many pages feel like they’ve been recycled, or like you’ve entered a time warp that moves you backward, page-wise. Yes, there are uplifting accounts of readings that Holp has done with clients here, and they’re exciting but there are too few of them. When you find them, you’ll love them. They may make you cry. They’re exactly what you need, if you grieve. Just not enough.

This isn’t a terrible book, but its audience might be narrow. It absolutely needs more stories, less sentiment; more tales, less transcendence and if that’s your aim, go elsewhere. But if your soul cries for comfort after loss, “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis” might still make sense.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.