Arts & Entertainment

Classical closet?

Van Cliburn’s death inspires questions about how elite music treats its gay icons

Van Cliburn (Photo by David Eldan via Wikimedia Commons)

It was publicly acknowledged in obituaries in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times and at a funeral held last weekend that concert pianist Van Cliburn, one of the most famous classical musicians of the 20th century, was gay, but the references — the “g” word was not used — were as discreet and low key as the keyboard virtuoso was in his lifetime.

Cliburn, whose triumph at the 1958 International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow at age 23 was the crowning achievement of what had been a white-hot track record of competition winning and concertizing after a lauded three-year stint at the famous Juilliard School, died Feb. 27 at his home in Fort Worth, Texas, at age 78 following a battle with bone cancer. The story of his win in Moscow at the height of the Cold War when he was exalted as a symbol of overcoming the fear and paranoia of the era with great art, has been oft told, especially over the last week as his life has been remembered and celebrated. The long decades since it happened have cemented its mythic status and though Cliburn’s return to performing in the late ‘80s and ‘90s after nearly a decade-long hiatus drew mixed reviews, the fire and talent he brought to his early career is pretty much universally acknowledged by critics.

Cliburn plays Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No.1 Mvt III

“With the iconic nature of his rise to fame so to speak, he really became this symbol because what really happened there in Moscow was about so much more than the music,” says Scott Beard, a gay concert pianist and professor at West Virginia’s Shepherd University. “It wasn’t like Glenn Gould with the ‘Goldberg Variations,’ it was a highly politicized thing and to [Nikita] Khruschev’s credit, he said, ‘He’s the best, he should win.’ I think with that came a lot of pressure.”

And while one wouldn’t expect Cliburn to have been out at the time — it was, after all, only a year after gay rights pioneer Frank Kameny was fired by the U.S. government for being gay and years before Stonewall — Cliburn’s low-key handling of his homosexuality has been so understated that, at times, the references to it in mainstream media outlets are almost, one might argue, comically opaque.

The Los Angeles Times mentioned “Thomas L. Smith, his friend and manager who survives him.” The New York Times said he was “survived by [Smith], with whom he shared his home for many years.” A 2008 New York Times article commemorating the 50th anniversary of his Tchaikovsky win, mentioned “his home in Fort Worth, which he shared with a longtime friend.” (Smith spoke briefly at Cliburn’s funeral saying, “Van’s death is a crater-sized void that is felt around the world but for me, it is the loss of my soul mate, the deepest friendship …”)

A sunny 1993 biography from Chicago Tribune arts critic Howard Reich is more than 400 pages long yet includes not one mention of Cliburn’s love life. (Reich wrote in an e-mail to the Blade this week regarding Cliburn that “my area of study is really the music itself.”)

There was one episode the papers did dutifully report — a former boyfriend, Thomas Zaremba, sued Cliburn in 1996 seeking millions in palimony. The suit was eventually dismissed. Cliburn did briefly comment on the matter at the time, telling the Fort Worth Star-Telegram it was “absolutely a shocking surprise.” Cliburn said there was no way he could have exposed Zaremba to HIV, as Zaremba had claimed, as Cliburn himself was negative.

If anything, though, the lawsuit did break the ice for acknowledgement of Cliburn’s being gay in the press. Although friends and associates who knew him early in his career say he was never particularly closeted, it was not a topic ever publicly discussed. Aside from the fact that more gays were in the closet in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s than today, the near-constant presence of Cliburn’s mother, the famous Rildia Bee O’Bryan Cliburn, who had been his first piano teacher, is generally acknowledged as a factor in his low-key lifestyle.

“When I first knew him, I knew he was gay from the very beginning, but I can’t remember quite how I knew,” says Robert Croan, a former classical music critic for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette who’s gay. “His mother, whom I met many times, was sort of a grand dame type, but very down to earth. She had a great sense of humor but she watched over him very carefully. I think he had his excursions with various men but she traveled with him and was just there all the time. … She was very proprietary with him and the father was sort of invisible as far as the public really knew.” (Cliburn’s father died in 1974.)

Croan says although he and Cliburn were not close friends, they were friendly over many years and saw each other multiple times, including when Croan covered the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, a highly regarded quadrennial contest Cliburn started in the late ’60s in Fort Worth, for the Post-Gazette. Croan helped facilitate an honorary doctorate for Cliburn from Pittsburgh’s Duquesne University, where Croan previously taught.

Fans inevitably wondered to what degree — if any — Cliburn was out to his mother. Cliburn never publicly commented on the matter.

“I would say she had to have known,” Croan says. “Whether they actually discussed it, I have no way of knowing but she couldn’t have been around him all that time and not known. This was not a stupid woman. … I would guess at the very least she closed her eyes to what was going on or maybe acknowledged it privately.”

But it’s unlikely Rildia Bee, who died in 1994 at age 97, was the only factor. Cliburn spent his later years living in his native Texas (in a swanky suburb of Fort Worth), was a lifelong Baptist, member and regular attendee at Fort Worth’s large Broadway Baptist Church and was also a Republican. Former President George W. Bush, also from Texas, spoke at Cliburn’s funeral. (In 2009, Cliburn’s church severed ties with the Southern Baptist Convention in a disagreement over the church’s welcoming of LGBT members.)

And for all his musical achievements, Cliburn — at least so far as is publicly known — was not involved in LGBT advocacy work of any kind.

Philip Johnson, an 87-year-old Fort Worth gay activist who worked with Kameny and was involved in LGBT work for decades, says, “I don’t think he ever associated with the gay movement at all.”

“I used to see him sometimes at the Highland Park Cafeteria, this place where wealthy people ate that had really excellent food,” Johnson says. “But we never crossed paths at any sort of gay rights rally or anything like that.”

Darren Woods, general director of the Fort Worth Opera, agrees.

“I did not know him well outside of his attending operas occasionally and the occasional hello at a restaurant,” Woods, who’s gay, wrote in an e-mail. “He and his long-time partner, Tommy, were deeply involved with many straight married couples who were big arts patrons.”

SIDEBAR: Mono recording of Cliburn’s Moscow triumph available

The degree to which Cliburn was out at various periods of his life, while interesting enough in and of itself, also raises a bounty of other questions. Were many classical pianists of Cliburn’s day — Liberace, for the record, was considered more of a pop entertainer and was never taken seriously by the classical establishment — gay? If so, how many were out? Are the numbers any different today? How does it compare to other classical professionals such as orchestra players, conductors and composers? And did the classical world warm to out gays more quickly than pop culture? Or the world at large? Or did the blue-blooded, elderly art patron types keep gays in the closet longer? And with so much emphasis in pop culture with who’s sleeping with whom and the personal lives of celebrities, why do such questions seldom get asked of classical artists?

Nobody has numbers, but the anecdotal assessments are entertaining.

“Generally it’s thought that a lot of concert pianists were gay,” says David Patrick Stearns, a classical music critic at the Philadelphia Inquirer, who’s gay. “Nobody really knows why, but it seems to be somewhere around 50 percent. Violinists? Almost never. Again, nobody really knows why. Cellists? That’s a little up for grabs. Organists? Almost all of them. Countertenors? Most of the American ones are gay, but the non-American ones are not. … Opera is kind of a separate thing. Opera, I mean talk about queer energy, though. I’ve heard people talk about there being straight opera queens but I don’t know.”

Croan says more American composers have traditionally tended to be gay than pianists.

“(Fellow Cliburn Juilliard pianist) John Browning was out,” Croan says. “Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti, certainly a large number of American composers of the mid-20th century were gay. Aaron Copland is another. They weren’t out in the sense that there was any public announcement about it and the media wouldn’t have touched on it unless there was some sort of a scandal, but it was kind of quietly acknowledged. I met a lot of gay performers of that generation. Some got married but most didn’t. Ned Rorem was gay and was very open about it in his memoirs.”

One wonders the degree to which this was acknowledged among the musicians themselves. Was anybody hosting pool parties on Sunday afternoons the way gay director George Cukor famously did in Hollywood?

“I don’t know about pool parties, but I think there was a large degree of socializing,” Croan says. “Classical music is a pretty small world to begin with so you have a smaller pool of people. … The difference from then and Van Cliburn is they didn’t all travel with their mothers, that’s a big difference. I think he stayed a bit more to himself in that way. … And I also think these groups could be very productive. It wasn’t all just drinking and carousing. Their interactions were very artistically productive. You had a lot of interaction and influence and a lot of good artistic results, ramifications.”

Stephen Hough, a highly regarded classical concert pianist who’s released many recordings, remembers a “wonderful evening” of dinner and a recital Cliburn gave at Tanglewood, an estate and music venue in Lenox and Stockbridge, Mass., in the ‘90s.

“I didn’t know him well but I found him to be a completely charming person at dinner,” Hough, who’s gay, says. “He was very humble and modest and always interested in what other people were saying. … He was a lovely person and I wish I’d been able to meet him more.”

Hough says many factors likely contributed to Cliburn’s discretion.

“He had a huge female audience,” Hough says. “Women always found him very attractive. He was sort of the perfect bachelor everyone wanted to marry. There were older women who simply fell at his feet. There’s a story I’m told where an older female fan greeted him once and told him with tears, ‘You’ve made my life worth living.’ He took her hands in his and held her to him and said, ‘This is such a special moment in my life, you’ve touched my heart deeply.’ Back in the earlier years, I don’t think his audience would have even known what homosexuality was much less accepted it. It was a much different era.”

Hough says he’s seen the matter handled in many different ways by classical performers over the years.

“Jorge Bolet was a pianist of the same generation as Cliburn,” he says. “He had a partner for decades who traveled with him always. He was just always there but it was never really laid out clearly who this was. You could think he was a boyfriend, you could think he was a secretary, a manager or whatever you chose, but there he was. We really shouldn’t demand too much heroism in the past because it was so different.”

As to how quickly the classical world warmed to the idea of its heroes being out, many say it pretty much mirrored the rates of society at large. It was never particularly unwelcoming, insiders say, but the seriousness with which its fans and artists approach their work made it perhaps an easier topic, historically, to avoid dealing with head on.

“Yes, you had all these staid, wealthy board members but they weren’t stupid people,” Croan says. “They put a blind eye to it in some ways, but they also liked socializing with the stars, just like they do in Hollywood. I’d say it was acknowledged on Broadway long before it was in Hollywood or in the classical music world. Broadway, I think, has always been pretty gay. I think Hollywood was probably the last. It was a medium for more people, more democratic and thus perhaps more conservative. You’d have children watching movies whereas classical music was pretty much an adult group.”

‘An old-fashioned institution’

Stearns says other arenas of performing lend themselves more easily to issues of sexuality.

“Movie stars and rock stars, too, they’re presented as these sexual objects so of course the public is interested in their sex lives,” he says. “But then you have people like [late gay pianist] Vladimir Horowitz and even gay people don’t want to know what he was doing in the bedroom. It’s a completely different playing field.”

The inherent formality in classical music is also a factor, it is widely thought.

“Classical music is a more old-fashioned institution,” Hough says. “You have Rufus [Wainwright] and he’s on stage singing songs he just wrote last year. I’m playing with a whole different flavor and a much longer time frame. It’s just generally a more formal art form. Some say they’d like us to come out in torn jeans and talking to the audience, but there’s also something about that formality that provides its own kind of theater in a way. When the lights go down and the conductor or soloist comes out, it’s a very theatrical moment and I think a certain amount of mystery can be a good thing.”

Hough says he experienced no backlash after coming out several years into his career. “A couple youngsters wrote to tell me I’d encouraged them,” he says. “Otherwise nothing good or bad really.”

Patricia Racette, currently on stage in the opera “Manon Lescaut” at the Kennedy Center, writes in an e-mail (she’s saving her voice, understandably, for the stage) that the demands placed on classical musicians are also a factor. Racette is in a lesbian relationship and has been out for years.

“We now live in a world inundated by reality TV,” she writes. “And the reality for a classical musician is the demand of a continually honed skill, never-ending study, preparation and execution of all of the above in order to sustain this unrelenting art form. While so many artists are indeed fascinating in their personal lives, the emphasis on the work (in classical music) is the most relevant.”

Racette, who earned her music degree from the University of North Texas, says she can relate to the conservative nature of the state being a factor in Cliburn’s quiet life.

“I was so buried in my music and working to pay for my school that I honestly did not tap into a specific LGBT community there,” she writes. “The campus itself was quite conservative making it a bit of a scary place to come into one’s own as it were.”

Others say too much personal information is sometimes seen as a distraction in classical music.

“I think it’s just the issue of let the music speak for itself,” Beard says. “Maybe on some level it helps to be out to help you build an audience … so I don’t know if it’s taboo per se, but … I think the focus is much more on the craft which I why maybe in a marketing sense you don’t see it more often. You want the music critics to take you seriously so you can imagine them thinking, ‘OK why are you telling me this, tell me how you play Beethoven,’ or whatever. It’s just kind of this unwritten thing of, ‘OK, you’re gay, you have your life, but the focus is not on your personal life.’”

Others are delighted to see how quickly the classical world and the world at large are changing in their acceptance.

Stearns says he and others at the Inquirer were debating how to address or broach the topic of the personal life of Yannick Nezet Seguin, who’s gay and last September became music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

“We were all thinking, ‘OK, how do we handle this?’” Stearns says. “People are always curious. They want to know who the wife is but we don’t out people at the Inquirer so, the mayor was there and said, ‘We welcome Yannick and his partner,’ and it was like, ‘OK, thank you.’” … Three or four years ago, I would have said yes, there might have been some squeamishness, but nobody batted an eye. Now he’s the first conductor of one of the five biggest orchestras in the country to be out. And, you know, Philly isn’t known to be the most progressive town on the planet. I think people were just really glad to just sort of snag this really wonderful up-and-coming talent. He’s very extroverted and a real people person and people are just really drawn to him and his boyfriend.”

Charles Miller, organist and music director at Washington’s National City Christian Church, says it’s up to each public figure to decide how to handle it depending on his or her comfort level.

“I think there are some good examples even in pop culture,” Miller, who’s gay, says. “You think of someone like David Hyde Pierce. We all know now and he’s never really shied away from it, but he’s not flaunting himself or his partner or activities in every magazine. In some cases, it’s the artist sort of preserving something of their lives under wraps so that it doesn’t detract from the art form. … [With Cliburn], you wouldn’t just have expected, now it’s the 2000s we’re gonna see him come flying out of the closet and jump up on a float. It’s really the individual’s preference of how they want to live their life.”

Cliburn did eventually tire of public life and for much of the ‘70s, lived quietly. He eventually returned to public life and performing and is widely acknowledged for starting the Cliburn Competition, but even so, there was an unexpected gay side to him in addition to his many eccentricities such as staying up all night, running late for recitals, hoarding antiques, opening recitals with “The Star-Spangled Banner” and saving dead flowers.

“If you really wanted to engage him and get him talking, you brought up Cher,” Stearns says with a hearty laugh. “He absolutely loved Cher.”

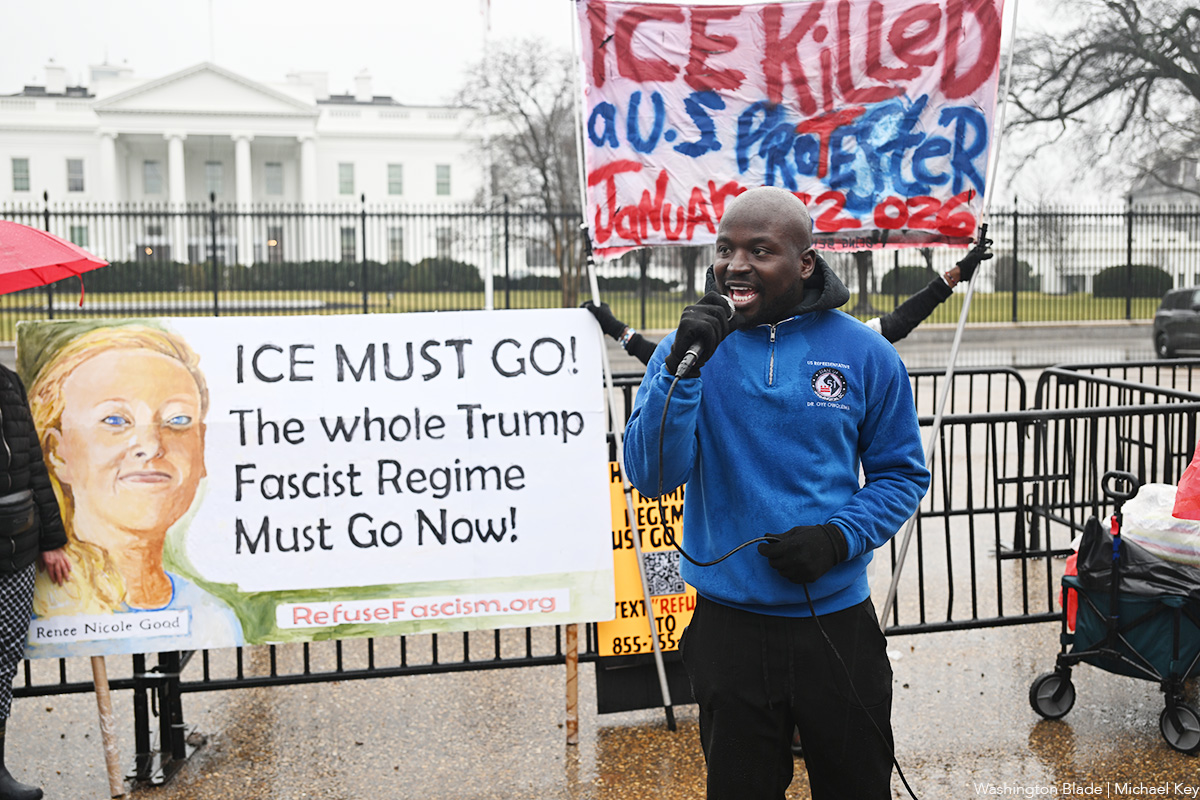

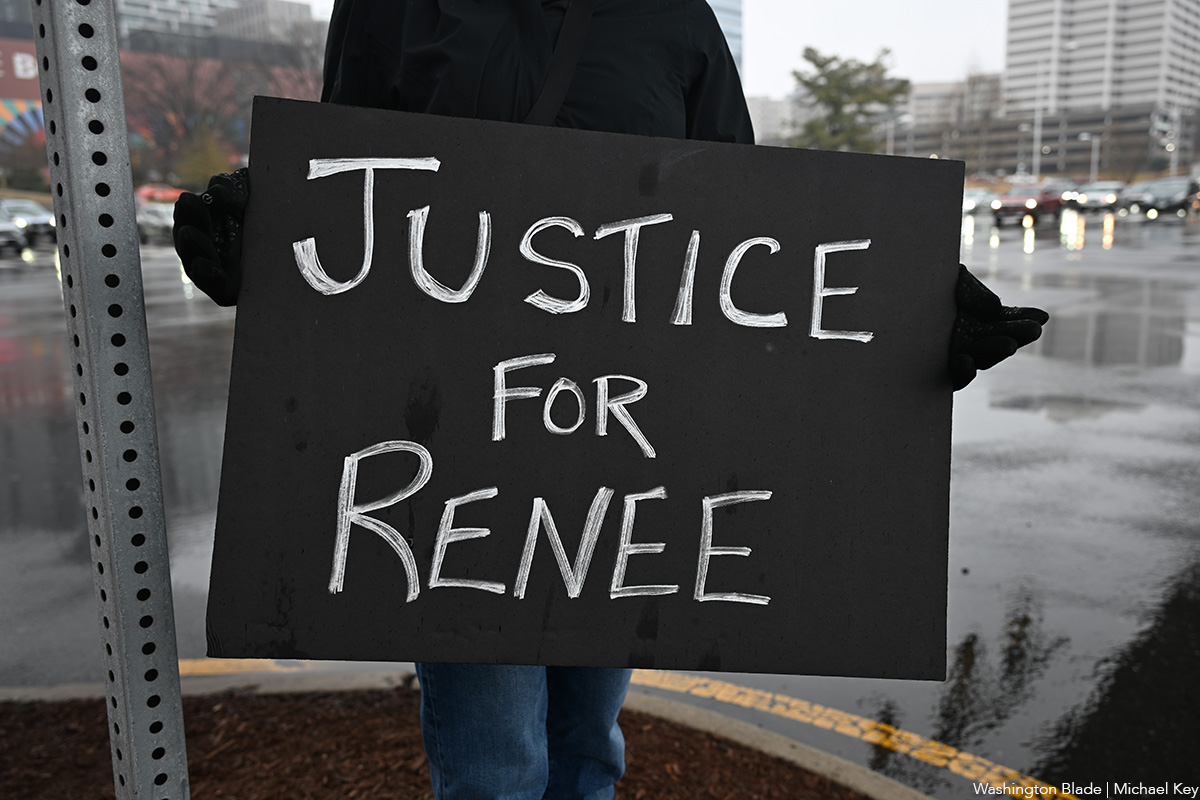

A protest was held outside of the White House on Saturday following the killing of Renee Nicole Good by a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent in Minneapolis. Across the Potomac, picketers held signs calling for “Justice for Renee” in Tysons, Va.

“ICE Out For Good” demonstrations were held in cities and towns across the country, according to multiple reports. A march was held yesterday in Washington, D.C., as the Blade reported. Further demonstrations are planned for tomorrow.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

Books

Feminist fiction fans will love ‘Bog Queen’

A wonderful tale of druids, warriors, scheming kings, and a scientist

‘Bog Queen’

By Anna North

c.2025, Bloomsbury

$28.99/288 pages

Consider: lost and found.

The first one is miserable – whatever you need or want is gone, maybe for good. The second one can be joyful, a celebration of great relief and a reminder to look in the same spot next time you need that which you first lost. Loss hurts. But as in the new novel, “Bog Queen” by Anna North, discovery isn’t always without pain.

He’d always stuck to the story.

In 1961, or so he claimed, Isabel Navarro argued with her husband, as they had many times. At one point, she stalked out. Done. Gone, but there was always doubt – and now it seemed he’d been lying for decades: when peat cutters discovered the body of a young woman near his home in northwest England, Navarro finally admitted that he’d killed Isabel and dumped her corpse into a bog.

Officials prepared to charge him.

But again, that doubt. The body, as forensic anthropologist Agnes Lundstrom discovered rather quickly, was not that of Isabel. This bog woman had nearly healed wounds and her head showed old skull fractures. Her skin glowed yellow from decaying moss that her body had steeped in. No, the corpse in the bog was not from a half-century ago.

She was roughly 2,000 years old.

But who was the woman from the bog? Knowing more about her would’ve been a nice distraction for Agnes; she’d left America to move to England, left her father and a man she might have loved once, with the hope that her life could be different. She disliked solitude but she felt awkward around people, including the environmental activists, politicians, and others surrounding the discovery of the Iron Age corpse.

Was the woman beloved? Agnes could tell that she’d obviously been well cared-for, and relatively healthy despite the injuries she’d sustained. If there were any artifacts left in the bog, Agnes would have the answers she wanted. If only Isabel’s family, the activists, and authorities could come together and grant her more time.

Fortunately, that’s what you get inside “Bog Queen”: time, spanning from the Iron Age and the story of a young, inexperienced druid who’s hoping to forge ties with a southern kingdom; to 2018, the year in which the modern portion of this book is set.

Yes, you get both.

Yes, you’ll devour them.

Taking parts of a true story, author Anna North spins a wonderful tale of druids, vengeful warriors, scheming kings, and a scientist who’s as much of a genius as she is a nerd. The tale of the two women swings back and forth between chapters and eras, mixed with female strength and twenty-first century concerns. Even better, these perfectly mixed parts are occasionally joined by a third entity that adds a delicious note of darkness, as if whatever happens can be erased in a moment.

Nah, don’t even think about resisting.

If you’re a fan of feminist fiction, science, or novels featuring kings, druids, and Celtic history, don’t wait. “Bog Queen” is your book. Look. You’ll be glad you found it.

Movies

A Shakespearean tragedy comes to life in exquisite ‘Hamnet’

Chloe Zhao’s devastating movie a touchstone for the ages

For every person who adores Shakespeare, there are probably a dozen more who wonder why.

We get it; his plays and poems, composed in a past when the predominant worldview was built around beliefs and ideologies that now feel as antiquated as the blend of poetry and prose in which he wrote them, can easily feel tied to social mores that are in direct opposition to our own, often reflecting the classist, sexist, and racist patriarchal dogma that continues to plague our world today. Why, then, should we still be so enthralled with him?

The answer to that question might be more eloquently expressed by Chloe Zhao’s “Hamnet” – now in wide release and already a winner in this year’s barely begun awards season – than through any explanation we could offer.

Adapted from the novel by Maggie O’Farrell (who co-wrote the screenplay with Zhao), it focuses its narrative on the relationship between Will Shakespeare (Paul Mescal) and his wife Agnes Hathaway (Jessie Buckley), who meet when the future playwright – working to pay off a debt for his abusive father – is still just a tutor helping the children of well-to-do families learn Latin. Enamored from afar at first sight, he woos his way into her life, and, convincing both of their families to approve the match (after she becomes pregnant with their first child), becomes her husband. More children follow – including Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe), a “surprise” twin boy to their second daughter – but, recognizing Will’s passion for writing and his frustration at being unable to follow it, Agnes encourages him to travel to London in order to immerse himself in his ambitions.

As the years go by, Agnes – aided by her mother-in-law (Emily Watson) and guided by the nature-centric pagan wisdom of her own deceased mother – raises the children while her husband, miles away, builds a successful career as the city’s most popular playwright. But when an outbreak of bubonic plague results in the death of 11-year-old Hamnet in Will’s absence, an emotional wedge is driven between them – especially when Agnes receives word that her husband’s latest play, titled “Hamlet,” an interchangeable equivalent to the name of their dead son, is about to debut on the London stage.

There is nothing, save the bare details of circumstance around the Shakespeare family, that can be called factual about the narrative told in “Hamnet.” Records of Shakespeare’s private life are sparse and short on context, largely limited to civic notations of fact – birth, marriage, and death announcements, legal documents, and other general records – that leave plenty of space in which to speculate about the personal nuance such mundane details might imply. What is known is that the Shakespeares lost their son, probably to plague, and that “Hamlet” – a play dominated by expressions of grief and existential musings about life and death – was written over the course of the next five years. Shakespearean scholars have filled in the blanks, and it’s hard to argue with their assumptions about the influence young Hamnet’s tragic death likely had over the creation of his father’s masterwork. What human being would not be haunted by such an event, and how could any artist could avoid channeling its impact into their work, not just for a time but for forever after?

In their screenplay, O’Farrell and Zhao imagine an Agnes Shakespeare (most records refer to her as “Anne” but her father’s will uses the name “Agnes”) who stands apart from the conventions of her town, born of a “wild woman” in the woods and raised in ancient traditions of mysticism and nature magic before being adopted into her well-off family, who presents a worthy match and an intellectual equal for the brilliantly passionate creator responsible for some of Western Civilization’s most enduring tales. They imagine a courtship that would have defied the customs of the time and a relationship that feels almost modern, grounded in a love and mutual respect that’s a far cry from most popular notions of what a 16th-century marriage might look like. More than that, they imagine that the devastating loss of a child – even in a time when the mortality rate for children was high – might create a rift between two parents who can only process their grief alone. And despite the fact that almost none of what O’Farrell and Zhao present to us can be seen, at best, as anything other than informed speculation, it all feels devastatingly true.

That’s the quality that “Hamnet” shares with the ever-popular Will Shakespeare; though it takes us into a past that feels as alien to us as if it took place upon a different planet, it evokes a connection to the simple experience of being human, which cuts through the differences in context. Just as the kings, heroes, and fools of Shakespeare’s plays express and embody the same emotional experiences that shape our own mundane modern lives, the film’s portrayal of these two real-life people torn apart by personal tragedy speaks directly to our own shared sense of loss – and it does so with an eloquence that, like Shakespeare’s, emerges from the story to make it feel as palpable as if their grief was our own.

Yes, the writing and direction – each bringing a powerfully feminine “voice” to the story – are key to the emotional impact of “Hamnet,” but it’s the performances of its stars that carry it to us. Mescal, once more proving himself a master at embodying the kind of vulnerable masculine tenderness that’s capable of melting our hearts, gives us an accessible Shakespeare, driven perhaps by a spark of genius yet deeply grounded in the tangible humanity that underscores the “everyman” sensibility that informs the man’s plays. But it’s Buckley’s movie, by a wide margin, and her bold, fierce, and deeply affecting performance gives voice to a powerful grief, a cry against the injustice and cruelty of what we fumblingly call “fate” that resonates deep within us and carries our own grief, over losses we’ve had and losses we know are yet to come, along with her on the journey to catharsis.

That’s the word – “catharsis” – that defines why Shakespeare (and by extension, “Hamnet”) still holds such power over the imagination of our human race all these centuries later. The circumstantial details of his stories, wrapped up in ancient ideologies that still haunt our cultural imagination, fall away in the face of the raw expression of humanity to which his characters give voice. When Hamlet asks “to be or not to be?,” he is not an old-world Danish Prince contemplating revenge against a traitor who murdered his father; he is Shakespeare himself, pondering the essential mystery of life and death, and he is us, too.

Likewise, the Agnes Shakespeare of “Hamnet” (masterfully enacted by Buckley) embodies all our own sorrows – past and future, real and imagined – and connects them to the well of human emotion from which we all must drink; it’s more powerful than we expect, and more cleansing than we imagine, and it makes Zhao’s exquisitely devastating movie into a touchstone for the ages.

We can’t presume to speak for Shakespeare, but we are pretty sure he would be pleased.

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoWhat to watch for in 2026: midterms, Supreme Court, and more

-

Colombia4 days ago

Colombia4 days agoGay Venezuelan man who fled to Colombia uncertain about homeland’s future

-

District of Columbia5 days ago

District of Columbia5 days agoImperial Court of Washington drag group has ‘dissolved’

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoKennedy Center renaming triggers backlash