Books

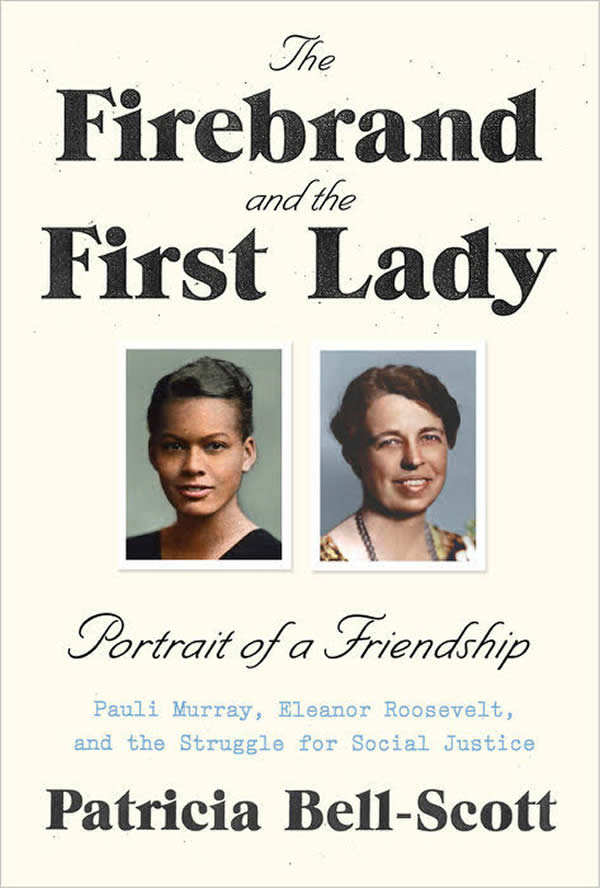

The friendship between a first lady and a ‘Firebrand’

Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt bonded during civil rights movement

Patricia Bell-Scott explores the friendship between Eleanor Roosevelt and Pauli Murray in her new book.

Most of us would be proud to have earned a degree, written an acclaimed book of poetry or memoir, worked tirelessly for civil rights and have been part of a friendship that fostered human rights.

Pauli Murray, the groundbreaking African-American activist, lawyer, writer and priest, who lived from 1910-1985 and was attracted to women, did all this and much more. For nearly 25 years, Murray the granddaughter of a mixed-race slave, was a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, whose privileged background entitled her to belong to the Daughters of the American Revolution. (Roosevelt resigned from the DAR in 1939 when the group prohibited the renowned African-American singer Marian Anderson from performing at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C.)

In her compelling new book “The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice,” Patricia Bell-Scott, editor of the anthology “All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave,” tells the story of this extraordinary relationship. Bell-Scott is professor emerita of women’s studies and human development and family science at the University of Georgia. Her previous books include: “Life Notes: Personal Writings by Contemporary Black Women” and “Double Stitch: Black Women Write about Mothers and Daughters,” which won the Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Book Prize.

From 1938-1962, their friendship was sustained by some 300 postcards and letters as well as personal visits. The relationship began when Murray, 27, working for the WPA, a New Deal agency, sent Eleanor Roosevelt a letter protesting a speech Franklin Delano Roosevelt had made at the University of North Carolina. (The university had refused to admit Murray as a student because she was black.) The friendship continued until Roosevelt, 26 years older than Murray, died in 1962.

Murray earned three law degrees, organized sit-ins in the 1940s while a student at Howard University against eateries that discriminated against people of color, participated in bus boycotts 15 years before Rosa Parks and created the legal strategy that ensured that sex discrimination was included in the Civil Rights Act.

A co-founder of the National Organization for Women, Murray wrote the memoir “Proud Shoes,” the well-regarded poetry collection “Dark Testament” as well as numerous essays and books. In 1977, she became one of the first women to be ordained as a priest by the Episcopal Church. Though Murray hadn’t been involved in writing it, in 1971 Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in an homage to Murray’s work, listed her as a co-author in her first brief before the Supreme Court.

Born in Baltimore, Murray didn’t use her given name “Anna Pauline.” Her father was a teacher and her mother was a nurse. At age three, after her mother died, Murray went to Durham, N.C., where she lived with her grandparents and two of her aunts, one of whom became her adoptive mother. In her childhood, Murray’s father, after contracting what was thought to be encephalitis, suffered from “unpredictable attacks of depression and violent moods.” Murray wasn’t ashamed of her sexual orientation and was in a long-term relationship with Irene, “Renee” Barlow. Yet, because of homophobia and her race, she was often denied employment in the government and the private sector.

It’s no wonder that it took Bell-Scott 20 years to write “Firebrand.” Recently, she talked with the Blade about the book and the friendship between Murray and the woman, who Murray called “Mrs. R.”

“This was not something I intended to do,” Bell-Scott said of “Firebrand.” “I was working on another project at the time.”

Then in 1983, Bell-Scott asked Murray to serve as a consulting editor to “SAGE: A Scholarly Journal of Black Women,” of which she was a co-founding editor. Though Murray couldn’t do SAGE, she wrote a letter of “encouragement” to Bell-Scott. “Pauli wanted to work on her autobiography,” she said.

In a follow-up to this letter, Murray wrote to Bell-Scott, “You need to know some of the veterans of the battle whose shoulders you now stand on.”

She didn’t say, “know me better,” Bell-Scott said, “but she did say she took great pride in her work as a member of the subcommittee on legal rights of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women. (President John F. Kennedy appointed Eleanor Roosevelt chair of the commission.)

Bell-Scott made notes of what she wanted to talk about with Murray when her writing project was finished. “But I didn’t get the chance —18 months later, she died of pancreatic cancer,” she said. “Her letter haunted me. Quite a few years later, I decided I was still so haunted by her comment about knowing the veterans on whose shoulders you’re standing on.”

After examining the collection of Murray’s letters at the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University and the collection of Roosevelt’s letters at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Bell-Scott said, she “immediately recognized that their relationship deserved attention.” Their friendship is mentioned only briefly by historians and biographers.

Despite the fact that Murray and Roosevelt came from very different backgrounds, they had a lot in common, Bell-Scott said. “To begin with, Anna was the given name for both of them and they never used it,” she said. “They both lost their parents before their teens and were sent to live with elderly kin.”

They were sensitive kids who grew up to be compassionate women with a thirst for justice, Bell-Scott said. “Even though she was first lady, people made fun of Eleanor’s appearance and ridiculed her teeth,” she added. “Pauli was boyish looking. People poked fun at how she looked.”

Murray and Roosevelt loved their fathers who suffered from mood disorders and alcoholism respectively. Though they were outspoken and highly energetic in their quest for social justice, “people were often surprised to learn that Pauli and Eleanor were both shy,” Bell-Scott said. “It took them tremendous psychic energy to overcome their shyness.”

Both were voracious readers and avid writers. Though she was a committed social justice activist, lawyer and priest, writing was what was closest to Murray’s heart, Bell-Scott said. “Pauli couldn’t turn away from activism,” she said, “but if there were any regrets – she would have liked to have written more.”

Roosevelt, too, was committed to her writing, Bell-Scott said. “Eleanor wrote her ‘My Day’ column even when she was first lady,” she said. “After FDR’s death, she reported on Russia and pursued other writing projects.”

Their sense of well being was dependent on having meaningful work and exercise, Bell-Scott said. “They had a talent for friendship. And they loved dogs. Eleanor liked Scotties and Pauli liked mutts and strays.”

Murray would work herself into exhaustion and crash, Bell-Scott said. “She suffered from mood swings which weren’t properly diagnosed as a thyroid disorder until Pauli was in her 40s,” she said. “Eleanor suffered episodes of depression.”

Their friendship was the context that allowed Murray and Roosevelt to grow into the “transformative leaders that we know them as,” Bell-Scott said. “When they first met, Pauli was an impatient young radical … Eleanor felt it was important to always consider taking social justice action with great caution – to always follow the muted action on civil rights of the Roosevelt administration.” (FDR never publicly pushed Congress to speak out against lynching, Bell-Scott said.)

Later in their lives, Bell-Scott said, Murray had moved from radical left to left of center – voting for Lyndon Johnson as a registered Democrat after decades of voting for Socialist candidates. By the 1960s, Roosevelt had put her life on the line at civil rights workshops and demonstrations.

“When I look at the issue of Pauli’s sexuality, I think of the social context of the time. Here is a woman coming to adulthood in the 1920s, 30s and 40s,” she said. “Homosexuality is defined as a mental disorder until the 1970s. Pauli, a very bright woman, reads the scientific literature.”

Added to this, Bell-Scott said, was the homophobia of McCarthyism, which considered LGBT people to be a security threat. “Pauli was a black woman lawyer,” she said, “ that’s an unconventional career for a woman. There are rumors about her sexuality and her mental health. She is living with discrimination on so many fronts.”

But Murray wasn’t ashamed of who she was, Bell-Scott said. “She was raised as a child by elder kin with Victorian values. You didn’t talk about sexuality.”

From reading Murray’s letters and sermons from later in her life, “it seems to me that Pauli began to publicly embrace herself,” Bell-Scott said.

Books

New book offers observations on race, beauty, love

‘How to Live Free in a Dangerous World’ is a journey of discovery

‘How to Live Free in a Dangerous World: A Decolonial Memoir’

By Shayla Lawson

c.2024, Tiny Reparations Books

$29/320 pages

Do you really need three pairs of shoes?

The answer is probably yes: you can’t dance in hikers, you can’t shop in stilettos, you can’t hike in clogs. So what else do you overpack on this long-awaited trip? Extra shorts, extra tees, you can’t have enough things to wear. And in the new book “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” by Shayla Lawson, you’ll need to bring your curiosity.

Minneapolis has always been one of their favorite cities, perhaps because Shayla Lawson was at one of Prince’s first concerts. They weren’t born yet; they were there in their mother’s womb and it was the first of many concerts.

In all their travels, Lawson has noticed that “being a Black American” has its benefits. People in other countries seem to hold Black Americans in higher esteem than do people in America. Still, there’s racism – for instance, their husband’s family celebrates Christmas in blackface.

Yes, Lawson was married to a Dutch man they met in Harlem. “Not Haarlem,” Lawson is quick to point out, and after the wedding, they became a housewife, learned the language of their husband, and fell in love with his grandmother. Alas, he cheated on them and the marriage didn’t last. He gave them a dog, which loved them more than the man ever did.

They’ve been to Spain, and saw a tagline in which a dark-skinned Earth Mother was created. Said Lawson, “I find it ironic, to be ordained a deity when it’s been a … journey to be treated like a person.”

They’ve fallen in love with “middle-American drag: it’s the glitteriest because our mothers are the prettiest.” They changed their pronouns after a struggle “to define my identity,” pointing out that in many languages, pronouns are “genderless.” They looked upon Frida Kahlo in Mexico, and thought about their own disability. And they wish you a good trip, wherever you’re going.

“No matter where you are,” says Lawson, “may you always be certain who you are. And when you are, get everything you deserve.”

Crack open the front cover of “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” and you might wonder what the heck you just got yourself into. The first chapter is artsy, painted with watercolors, and difficult to peg. Stick around, though. It gets better.

Past that opening, author Shayna Lawson takes readers on a not-so-little trip, both world-wide and with observant eyes – although it seems, at times, that the former is secondary to that which Lawson sees. Readers won’t mind that so much; the observations on race, beauty, love, the attitudes of others toward America, and finding one’s best life are really what takes the wheel in this memoir anyhow. Reading this book, therefore, is not so much a vacation as it is a journey of discovery and joy.

Just be willing to keep reading, that’s all you need to know to get the most out of this book. Stick around and “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” is what to pack.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Story of paralysis and survival features queer characters

‘Unswerving: A Novel’ opens your eyes and makes you think

‘Unswerving: A Novel’

By Barbara Ridley

c.2024, University of Wisconsin Press

$19.95 / 227 pages

It happened in a heartbeat.

A split-second, a half a breath, that’s all it took. It was so quick, so sharp-edged that you can almost draw a line between before and after, between then and now. Will anything ever be the same again? Perhaps, but maybe not. As in the new book “Unswerving” by Barbara Ridley, things change, and so might you.

She could remember lines, hypnotizing yellow ones spaced on a road, and her partner, Les, asleep in the seat beside her. It was all so hazy. Everything Tave Greenwich could recall before she woke up in a hospital bed felt like a dream.

It was as though she’d lost a month of her life.

“Life,” if you even wanted to call it that, which she didn’t. Tave’s hands resembled claws bent at the wrist. Before the accident, she was a talented softball catcher but now she could barely get her arms to raise above her shoulders. She could hear her stomach gurgle, but she couldn’t feel it. Paralyzed from the chest down, Tave had to have help with even the most basic care.

She was told that she could learn some skills again, if she worked hard. She was told that she’d leave rehab some day soon. What nobody told her was how Les, Leslie, her partner, girlfriend, love, was doing after the accident.

Physical therapist Beth Farringdon was reminded time and again not to get over-involved with her patients, but she saw something in Tave that she couldn’t ignore. Beth was on the board of directors of a group that sponsored sporting events for disabled athletes; she knew people who could serve as role models for Tave, and she knew that all this could ease Tave’s adjustment into her new life. It was probably not entirely in her job description, but Beth couldn’t stop thinking of ways to help Tave who, at 23, was practically a baby.

She could, for instance, take Tave on outings or help find Les – even though it made Beth’s own girlfriend, Katy, jealous.

So, here’s a little something to know before you start reading “Unswerving”: author Barbara Ridley is a former nurse-practitioner who used to care for patients with spinal cord injuries. That should give readers a comfortable sense of satisfaction, knowing that her experiences give this novel an authenticity that feels right and rings true, no faking.

But that’s not the only appeal of this book: while there are a few minor things that might have readers shaking their heads (HIPAA, anyone?), Ridley’s characters are mostly lifelike and mostly likable. Even the nasties are well done and the mysterious character that’s there-not-there boosts the appeal. Put everyone together, twist a little bit to the left, give them some plotlines that can’t ruined by early guessing, and you’ve got a quick-read novel that you can enjoy and feel good about sharing.

And share you will because this is a book that may also open a few eyes and make readers think. Start “Unswerving” and you’ll (heart) it.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Examining importance of queer places in history of arts and culture

‘Nothing Ever Just Disappears’ shines with grace and lyrical prose

‘Nothing Ever Just Disappears: Seven Hidden Queer Histories’

By Diarmuid Hester

c.2024, Pegasus Books

$29.95/358 pages

Go to your spot.

Where that is comes to mind immediately: a palatial home with soaring windows, or a humble cabin in a glen, a ramshackle treehouse, a window seat, a coffeehouse table, or just a bed with a special blanket. It’s the place where your mind unspools and creativity surges, where you relax, process, and think. It’s the spot where, as in the new book “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” by Diarmuid Hester, you belong.

Clinging “to a spit of land on the south-east coast of England” is Prospect Cottage, where artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman lived until he died of AIDS in 1994. It’s a simple four-room place, but it was important to him. Not long ago, Hester visited Prospect Cottage to “examine the importance of queer places in the history of arts and culture.”

So many “queer spaces” are disappearing. Still, we can talk about those that aren’t.

In his classic book, “Maurice,” writer E.M. Forster imagined the lives of two men who loved one another but could never be together, and their romantic meeting near a second-floor window. The novel, when finished, “proved too radical even for Forster himself.” He didn’t “allow” its publication until after he was dead.

“Patriarchal power,” says Hester, largely controlled who was able to occupy certain spots in London at the turn of the last century. Still, “queer suffragettes” there managed to leave their mark: women like Vera Holme, chauffeur to suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst; writer Virginia Woolf; newspaperwoman Edith Craig, and others who “made enormous contributions to the cause.”

Josephine Baker grew up in poverty, learning to dance to keep warm, but she had Paris, the city that “made her into a star.” Artist and “transgender icon” Claude Cahun loved Jersey, the place where she worked to “show just how much gender is masquerade.” Writer James Baldwin felt most at home in a small town in France. B-filmmaker Jack Smith embraced New York – and vice versa. And on a personal journey, Hester mourns his friend, artist Kevin Killian, who lived and died in his beloved San Francisco.

Juxtaposing place and person, “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” features an interesting way of presenting the idea that both are intertwined deeper than it may seem at first glance. The point is made with grace and lyrical prose, in a storyteller’s manner that offers back story and history as author Diarmuid Hester bemoans the loss of “queer spaces.” This is really a lovely, meaningful book – though readers may argue the points made as they pass through the places included here. Landscapes change with history all the time; don’t modern “queer spaces” count?

That’s a fair question to ask, one that could bring these “hidden” histories full-circle: We often preserve important monuments from history. In memorializing the actions of the queer artists who’ve worked for the future, the places that inspired them are worth enshrining, too.

Reading this book may be the most relaxing, soothing thing you’ll do this month. Try “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” because it really hits the spot.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

State Department3 days ago

State Department3 days agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoJoe Vogel campaign holds ‘Big Gay Canvass Kickoff’

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoSmithsonian staff concerned about future of LGBTQ programming amid GOP scrutiny

-

District of Columbia1 day ago

District of Columbia1 day agoCatching up with the asexuals and aromantics of D.C.