Commentary

One non-binary person’s perspective on how to transition thoughtfully and safely

Q and A: Transitioning and its long-term impact

Miami and Baltimore– Urban Health Media Project reporter Vanessa Falcon, a high school student in Miami, interviewed Arin Jayes, 30, of Baltimore, about his gender identity journey and experience transitioning to a non-binary trans man. Jayes, a behavioral health therapist, is also an urban farmer and embroidery artist.

Q: How was your transitioning process? Was it overall very difficult? Why? How long did it last?

A: As a non binary person, I have a flexible view of how individuals develop their gender identity. It’s something that may evolve throughout a person’s lifetime, based on experiences; changes in personal values and relationships; bodily changes; and other factors. Gender identity also intersects and interacts with many other identities, such as race, ethnicity, physical ability or disability, sexual orientation and class.

For many trans folks, the gender transition process is lifelong and never-ending! Pronouns can change multiple times (hence the “pronoun check” posts we see on Facebook). Similarly, physical changes or adjustments may happen over years, instead of all at once. I mention this before bringing up my own story because it is important to normalize the idea of flexible, changing genders. After all, gender is a social construct designed to categorize people. When we view gender on a continuum, we can recognize a galaxy of gender journeys that a person can take.

My own transition is a prime example. I came out as genderqueer in 2012, and used “they/them” pronouns exclusively. In 2015, after further introspection, I realized that I wanted to live in a more masculine body. I came out to my family and friends as a non-binary trans man, using “he” pronouns and physically transitioning. I made this decision with the understanding that I wasn’t transitioning because I identified as a “man” per se, but that I felt more comfortable in a body that had more masculine characteristics. Since physically transitioning seven years ago, I’ve passed as male about 90% of the time. (Masks can sometimes make passing complicated for trans folks!) When people ask me nowadays what my gender is, I just say “non-binary,” and that my pronouns are “he or they — either as fine.” I am leaning into presenting as femme or as masc as I want on any given day, and being as gay as I want. It can be tempting to present in a way that is more conventionally masculine or feminine, because sometimes it is just easier (fewer questions, comments, or worse). But if COVID-19 has taught me anything, it is that time is not guaranteed, and we must consider what makes life worth living, and embrace it. Every time Pride Month rolls around, I recommit to my true self. But this year it feels all the more important.

Q: Throughout the transitioning journey, many clients are informed of possible negative side effects. Despite hearing about them, you still decided to transition. Why?

A: Deciding to transition was one of the most important and difficult decisions I have ever made. Like many trans people, I didn’t initially know what being transgender meant. I had to do a lot of research, introspection and support group work before I realized that being transgender described how I felt. When deciding whether to physically transition, a person can do research about the changes that they may experience, talk to other people that have gone through similar changes, and seek individual or group therapy for support. I decided to physically transition after weighing my options based on the information that I gathered, the changes that I wanted, and my financial budget.

Luckily, there is a lot of information and help available. Trans folks are resourceful, and do a lot to support and inform our communities. For example, there are numerous databases developed by trans people for trans people that allow you to review different surgeons or healthcare providers; compare photos or results of surgeries; and share resources and educational information about physically transitioning. Many community mental health centers have legal clinics that help people navigate the name and gender marker change process.

One side effect that I didn’t entirely understand until after I transitioned was the significant impact that being transgender has on how we navigate the world. It affects where we go to school and receive healthcare, even which streets we choose to walk down late at night. On a job interview, we often feel the need to consider, “Will people here be accepting of me? Will there be a restroom that I can safely use?” As a white and masculine-adjacent person, my navigation of the world is privileged based on systems of white supremacy. I will not for a second forget the trans women of color who paved the way for us to demand justice; their leadership — and that of their successors in our movements — must be recognized.

Q: Did you have, or do you currently have, any regrets about transitioning?

A: What I think this question is getting at is, “How do you know you’re sure?” This was a question that I asked myself many times as I considered making irreversible (or at least, not easily reversible) changes to my body. My answer to that is: I didn’t truly know it was right until after I did it. That may seem radical or scary. One may ask, “Why on earth would you do something so permanent if you weren’t sure?” But It took a leap of faith. And, as someone who has been there, I can say that if it doesn’t feel right, you know. It is important to trust yourself and your bodily autonomy. Also, if you decide to stop your physical transition, you don’t need to think of it as “de-transitioning.” The path of your gender journey is unique to you. You call the shots.

Q: How has transitioning helped you and your image of yourself? How has it affected your self-esteem and mental health?

A: Much of what is written about trans people focuses on the challenges of being trans. While I said that deciding to transition was one of the most important and difficult decisions I ever made, it was also one of the best ones I ever made. I love being trans! Trans people are unique, creative, and resilient. Trans culture is rooted in grassroots community organizing. It is humbling to think of all the amazing thinkers, writers, and artists who walked this journey. I have had the privilege to meet a lot of amazing trans people who remind me of the power of our community.

Q: What advice would you give to other people who want to follow the path you did?

A: Despite what society tells you about bodies and gender, there are no rules! You don’t have to justify or explain to anyone your decision to transition. You’re in the driver’s seat. Your body belongs to you and no one else. You will live in your body for the rest of your life. Therefore, you get to decide on what terms you will occupy it.

This article is part of our 2021 Youth Pride Issue in partnership with Urban Health Media.

Commentary

Asian American and LGBTQ: A Heritage of Pride

May is Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (APIs) are the nation’s fastest growing racial minority group by 2040, one in 10 Americans will be of Asian ancestry. And, while many Americans think that anti-Asian hate and racism towards Asian Americans has disappeared, the community disagrees.

The Asian American Foundation which found that Asian Americans are continually subjected to hate, violence, and discrimination, baldly reveals that disparity.

- 33 percent of Americans think hate towards Asian Americans has increased in the past year, compared to 61 percent of Asian Americans themselves.

- In the past year, 32 percent of Asian Americans across the country reported being called a racial slur; 29 percent said they were verbally harassed or verbally abused.

- Southeast Asian Americans report even higher incidences of being subject to racial slurs (40 percent), verbal harassment or abuse (38 percent), and threats of physical assault (22 percent).

- Many Asian Americans live in a state of fear and anxiety with 41 percent of Asian American/ Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (AANHPI) believing they will likely be the victims of a physical attack due to their race, ethnicity, or religion. These numbers are disturbing.

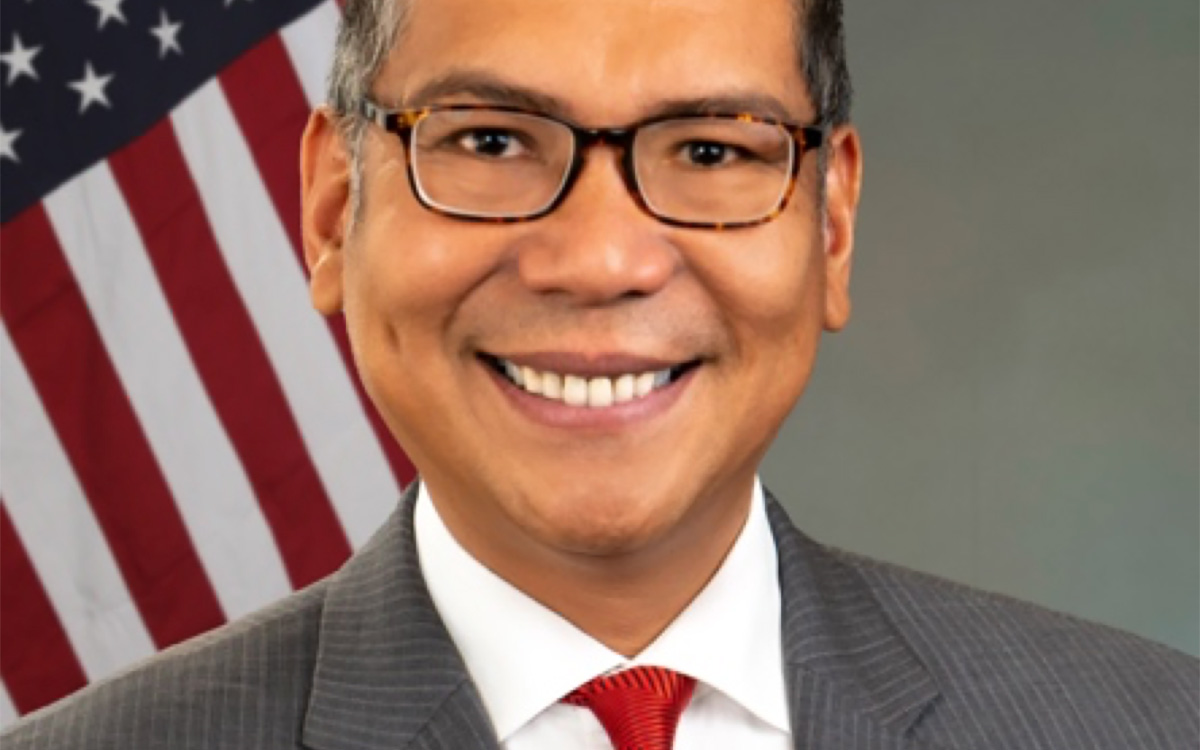

I serve as the only Asian American Pacific Islander member on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. And, I am the first and only queer AAPI on the U.S. commission. I am deeply honored to both serve my country and represent my Asian Americans and Pacific Islander community.

Last year, the commission investigated the Federal Response to Anti-Asian Racism in the United States. With congressional authorization, the report documented the experiences of AANHPIs in the U.S. since the dubbing of COVID-19 as the “China Virus” infecting people with the “Kung Flu” by government leadership. Words matter, as this report shows.

This report has a deep personal connection for me. I am the survivor of a hate crime of 25 years ago for being gay, and the victim of a hate crime for being Asian 25 months ago

The Stop AAPI Hate Coalition reported that bias incidents against individuals who are Asian and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ) were most prominent between 2019 and 2022, highlighting the intersectional nature of these incidents. For example, two transgender Asian women stated:

“I was with my new boyfriend at a restaurant. When we walked in the server started calling me names … a b—h, ch—k, tra—i.e. … He said I have a big fat p—s, and told me to go back to China. Then my boyfriend proceeded to walk in the restaurant and when I took a step forward, the server hit me, so I left.”

“Left a restaurant with friends in the Asian district of town. A man began to follow me calling out ‘Hey you f—got c—k!’ and ‘Come here you virus!’ I began to walk fast towards a crowd until he stopped following me.”

To address these and other equally appalling experiences, I helped shepherd the bipartisan Commission on Civil Rights recommendations to the president, Congress, and the nation that:

- Prosecutors and law enforcement should vigorously investigate and prosecute hate crimes and harassment against Asian Americans, as well as Asian Americans who are LGBTQ.

- First responders should be trained to understand what exactly constitutes a hate crime in their jurisdiction, including the protections of LGBTQ people.

- Federal, state, and local law enforcement and victim services should identify deficiencies in their programs for individuals with limited English proficiency.

Greater language access will make an enormous impact for the Asian American community as one in five Asian individuals speak a language other than English at home. A third (34 percent) is limited English proficient. The most frequently spoken languages are Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Tagalog, Thai, Khmer, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, and Punjabi.

For me, this report comes full circle. Since 1988, I’ve lobbied for passage of LGBTQ-inclusive federal and state laws to prevent hate crimes. Since 2001, I’ve supported South Asian and Muslim victims of post 9/11 violence. In response to the shootings at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla, in 2016; Atlanta Spa in Georgia in 2021; and Club Q in Colorado Springs, Colo., in 2022, I‘ve trained over 3,000 lawyers, law students, and community leaders on hate crimes law.

And yet, our work is not yet done.

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. June is LGBTQ Pride Month. Despite these challenges, we are resilient. Let us join together in celebrating our Heritage of Pride

Glenn D. Magpantay, Esq., is a long-time civil rights attorney, professor of law and Asian American Studies, and LGBTQ rights activist. Glenn is a founder and former Executive Director of the National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance (NQAPIA). He is principal at Magpantay & Associates: A nonprofit consulting and legal services firm. In 2023, the U.S. Senate (majority) appointed Glenn to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights to advise Congress and the White House on the enforcement of civil rights laws and development of national civil rights policy.

Commentary

Journalists are not the enemy

Wednesday marks five years since Blade reporter detained in Cuba

Wednesday marked five years since the Cuban government detained me at Havana’s José Marti International Airport.

I had tried to enter the country in order to continue the Washington Blade’s coverage of LGBTQ and intersex Cubans. I found myself instead unable to leave the customs hall until an airport employee escorted me onto an American Airlines flight back to Miami.

This unfortunate encounter with the Cuban regime made national news. The State Department also noted it in its 2020 human rights report.

Press freedom and a journalist’s ability to do their job without persecution have always been important to me. They became even more personal to me on May 8, 2019, when the Cuban government for whatever reason decided not to allow me into the country.

‘A free press matters now more than ever’

Journalists in the U.S. and around the world on May 3 marked World Press Freedom Day.

Reporters without Borders in its 2024 World Press Freedom Index notes that in Cuba “arrests, arbitrary detentions, threats of imprisonment, persecution and harassment, illegal raids on homes, confiscation, and destruction of equipment — all this awaits journalists who do not toe the Cuban Communist Party line.”

“The authorities also control foreign journalists’ coverage by granting accreditation selectively, and by expelling those considered ‘too negative’ about the government,” adds Reporters without Borders.

Cuba is certainly not the only country in which journalists face persecution or even death while doing their jobs.

• Reporters without Borders notes “more than 100 Palestinian reporters have been killed by the Israel Defense Forces, including at least 22 in the course of their work” in the Gaza Strip since Hamas launched its surprise attack against Israel on Oct. 7, 2023. Media groups have also criticized the Israeli government’s decision earlier this month to close Al Jazeera’s offices in the country.

• Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, Washington Post contributor and Russian opposition figure Vladimir Kara-Murza and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Alsu Kurmasheva remain in Russian custody. Austin Tice, a freelance journalist who contributes to the Post, was kidnapped in Syria in August 2012.

• Reporters without Borders indicates nearly 150 journalists have been murdered in Mexico since 2000, and 28 others have disappeared.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken in his World Press Freedom Day notes more journalists were killed in 2023 “than in any year in recent memory.”

“Authoritarian governments and non-state actors continue to use disinformation and propaganda to undermine social discourse and impede journalists’ efforts to inform the public, hold governments accountable, and bring the truth to light,” he said. “Governments that fear truthful reporting have proved willing to target individual journalists, including through the misuse of commercial spyware and other surveillance technologies.”

U.S. Agency for International Development Administrator Samantha Power, who is a former journalist, in her World Press Freedom Day statement noted journalists “are more essential than ever to safeguarding democratic values.”

“From those employed by international media organizations to those working for local newspapers, courageous journalists all over the world help shine a light on corruption, encourage civic engagement, and hold governments accountable,” she said.

President Joe Biden echoed these points when he spoke at the White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner here in D.C. on April. 27.

“There are some who call you the ‘enemy of the people,'” he said. “That’s wrong, and it’s dangerous. You literally risk your lives doing your job.”

I wrote in last year’s World Press Freedom Day op-ed that the “rhetoric — ‘fake news’ and journalists are the ‘enemy of the people’ — that the previous president and his followers continue to use in order to advance an agenda based on transphobia, homophobia, misogyny, islamophobia, and white supremacy has placed American journalists at increased risk.” I also wrote the “current reality in which we media professionals are working should not be the case in a country that has enshrined a free press in its constitution.”

“A free press matters now more than ever,” I concluded.

That sentiment is even more important today.

Commentary

A reporter’s observations on the Brazilian, U.S. elections

Polls in both countries proved inaccurate

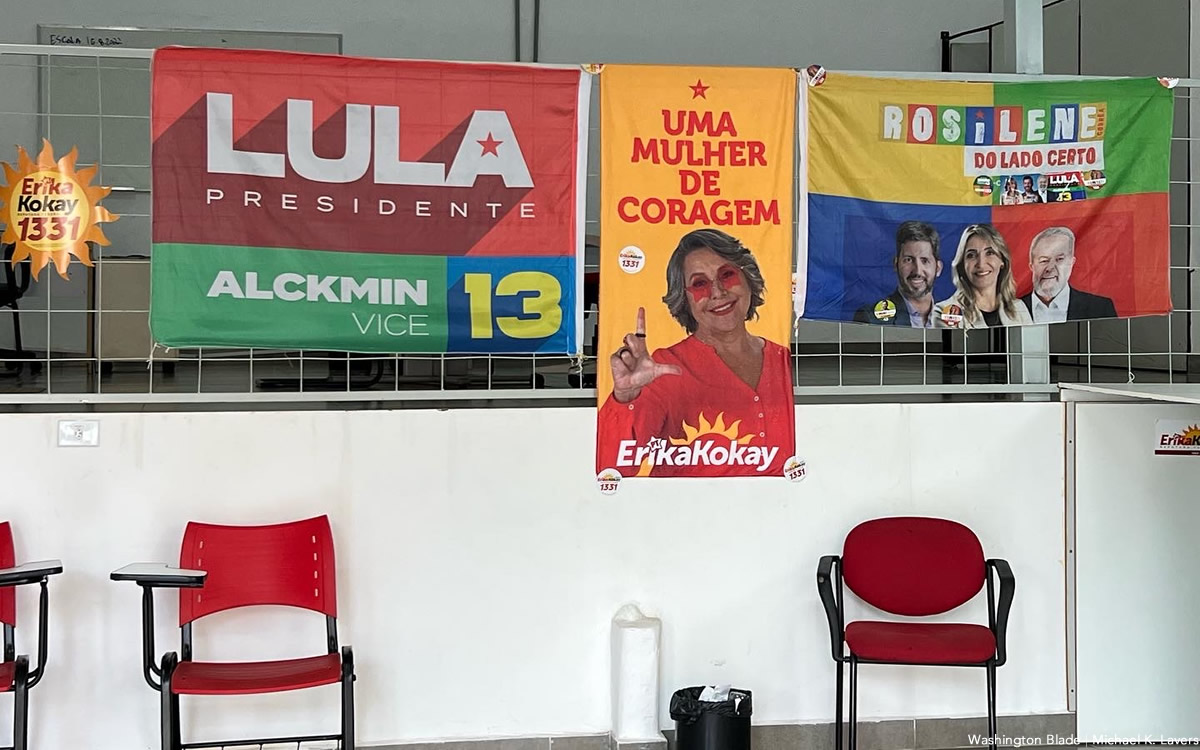

BRASÍLIA, Brazil / STEVENSVILLE, Md. — I was sitting in my hotel room in Brasília, the Brazilian capital, at 5 p.m. on Oct. 2 when the polls closed. The area around my hotel was quiet as the Supreme Electoral Tribunal began to post the election results on their website. Brazilian television stations continued their live coverage of the election that largely focused on whether former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva would defeat incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro. I was nibbling on KIND Dark Chocolate Whole Grain Clusters that I had bought at Dulles two days earlier before I flew to Brazil and sipping a glass of Brahma beer that I had poured for myself while refreshing the Supreme Electoral Tribunal’s website and listening to the reporters talk about the results. I was nervous because Bolsonaro was ahead.

I left my room at around 7 p.m. to get some dinner at a nearby mall. I ordered sushi from a restaurant in the food court. Bolsonaro was still ahead of Da Silva when I returned to my room at around 7:45 p.m., but the margin between the two men had narrowed. Da Silva soon took the lead, but it soon became clear that he and Bolsonaro would face each other in a runoff because neither of them had received at least 50 percent of the vote.

Da Silva defeated Bolsonaro in the second round of the presidential election that took place on Oct. 30. The U.S. midterm elections took place nine days later.

I arrived at Heather Mizeur’s election night party at the Kent Island Resort in Stevensville, Md., shortly before polls in Maryland closed at 8 p.m. Mizeur less than three hours later told her supporters that her bid to unseat Republican Congressman Andy Harris had come up short. The so-called red wave that so many pundits and polls predicted would elect Republicans across the country also failed to materialize.

Each country is different and the way they conduct their elections is difficult. I cannot, however, help but compare the Brazilian election and the U.S. midterms. Here are a few observations from a reporter who covered them both.

• Polls ahead of the first round of Brazil’s presidential election predicted Da Silva would defeat Bolsonaro in the first round. Polls and pundits ahead of the U.S. midterms, as previously noted, predicted Republicans would defeat Democrats across the country. Both scenarios did not happen.

• Bolsonaro ahead of Brazil’s presidential election sought to discredit the country’s electoral system. Bolsonaro did not concede to Da Silva after he lost. Former President Donald Trump continues to insist he won the 2020 presidential election. Trump also instigated the deadly Jan. 6 insurrection that took place as lawmakers were beginning to certify the Electoral College results.

• Cláudio Nascimento, president of Grupo Arco-Íris de Cidadania LGBT, an LGBTQ and intersex rights group in Rio de Janeiro, on Oct. 9 told me during an interview at his office that Bolsonaro would “destroy democracy”in Brazil if he were reelected. Mizeur in July described Harris as a “traitor to our nation” after the Jan. 6 committee disclosed he attended a meeting with Trump that focused on how he could remain in office after he lost to now President Joe Biden.

• Voters in São Paulo and Belo Horizonte on Oct. 2 elected two transgender women — Erika Hilton and Duda Salabert respectively — to the Brazilian Congress. Openly gay Rio Grande do Sul Gov. Eduardo Leite on Oct. 30 won re-election when he defeated former Bolsonaro Chief-of-Staff Onyx Lorenzoni in a runoff. LGBTQ Victory Fund President Annise Parker in a Nov. 10 statement noted 436 openly LGBTQ candidates across the country won their races. (One of them, openly gay New Hampshire Congressman Chris Pappas, who represents my mother, defeated Republican Karoline Leavitt in the state’s 1st Congressional District by a 54-46 percent margin.)

Brazil and the U.S. are different countries, but they both have democracies that must be defended. Brazilians and Americans did just that through their votes.

-

U.S. Supreme Court3 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court3 days agoSupreme Court to consider bans on trans athletes in school sports

-

Out & About3 days ago

Out & About3 days agoCelebrate the Fourth of July the gay way!

-

Virginia3 days ago

Virginia3 days agoVa. court allows conversion therapy despite law banning it

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoLGBTQ suicide prevention hotline option is going away. Here’s where else to go in Md.