Commentary

‘Did this really just happen to me?’

Cuban cell phone was only link to outside world

MIAMI BEACH, Fla. — Wednesday was to have been the first day of my seventh trip to Cuba. The country’s government put a quick end to that plan.

My American Airlines flight from Miami landed at Havana’s José Martí International Airport shortly before noon. I was one of the first passengers off the plane.

There were a few dozen people — mostly customs employees — in the large customs hall downstairs when I approached an officer who was sitting in one of the more than a dozen booths. I said “good afternoon” to her in Spanish and handed her my passport and “tourist card” visa that I bought after I purchased my flights last month. She began to enter my information into a computer and after a couple of minutes she told me to stand behind the line at which people wait before they approach the booths.

A woman who I later realized was a customs manager — who subordinates called “la jefa” or “the boss” in Spanish — approached me and asked for my passport and visa. I gave them to her, and then walked over to where Cleve Jones — a San Francisco-based activist who was to have been the grand marshal of a government-approved International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia march in Havana that was cancelled earlier in the week with little explanation — and two other Americans who were on my flight were waiting for a contact to escort them through customs. The four of us chatted for a few minutes until the customs manager called my name. I walked over to her and a male colleague with whom she was standing asked me three questions: How many times have I been to Cuba? What is my profession? What was the purpose of my trip? I answered each of the three questions and the man then told me I was not allowed to enter the country. I asked him why and the only thing he said was my name was on a list. He directed me to a row of seats near an emergency exit and I sat there with my backpack, carry-on and a plastic bag with things I bought at Miami International Airport before the flight. Someone from Jones’ group asked me what was happening, and I said something to the effect that I was not being allowed into the country. I don’t know if they heard what I said.

I used my iPhone to call my husband in D.C. and text Washington Blade editor Kevin Naff to let them know what was happening. I also used my Cuban cell phone to call a contact in Havana. The person who escorted Jones and the other two Americans through customs arrived a short time later and they left about half an hour after our flight landed. I knew I was going to be on an American Airlines flight to Miami that was scheduled to leave at 7 p.m., but I asked the customs manager to confirm this information and to tell me why the government had refused to allow me to enter the country. She said she didn’t know and apologized to me. She also asked me if I wanted any water or food. I thanked her; but said no because I had a full water bottle, snacks and half a breakfast sandwich from Miami with me. I asked her if I could use the restroom. She said yes and I walked over by myself.

The thought of spending more than six hours in a Cuban airport was dreadful, but I was not overly scared because I had not been formally detained and the customs manager was doing what she could to keep me comfortable. I spent the next couple of hours walking back and forth to the restroom, pacing around the customs hall, using my iPhone’s notes app to write the Blade’s article about what happened and talking to a man from Angola who was not allowed to enter Cuba after he arrived on a flight from Panama. I also called a contact in Havana and told them I was “bored out of my mind.”

A contact in the U.S. called my iPhone at around 3 p.m., and I began to tell them what was happening. The customs manager and the same male colleague who told me I was not allowed to enter Cuba approached me about 15 minutes later and told me I could not use cell phones in the customs hall, even though several of their colleagues were using theirs. The customs manager then told me to turn off my iPhone and give it to her. She then told me she would keep it with my passport and give them back to me before I boarded my flight to Miami.

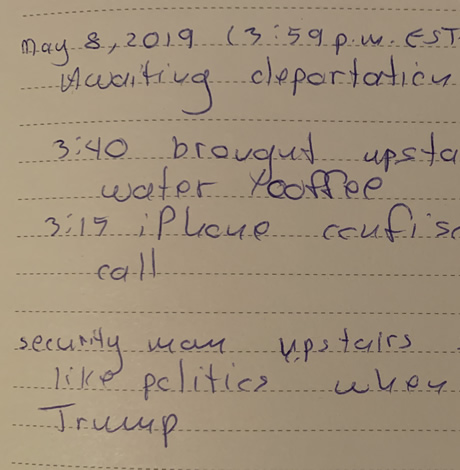

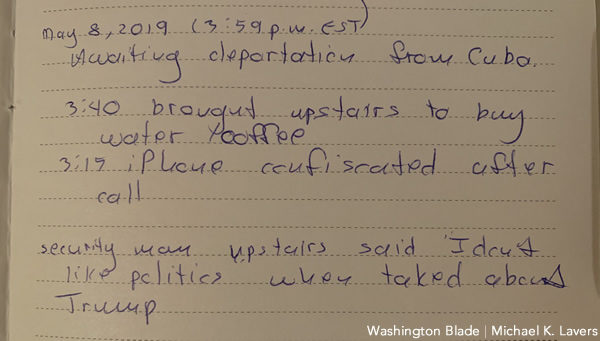

I felt even more disconnected from the world after they took my iPhone, but I still had my Cuban cell phone. I muted the ringer, placed it into the hat I was wearing and used it to text the contact in Havana with whom I was in contact and to and Maykel González Vivero, publisher of Tremenda Nota, the Blade’s media partner in Cuba. I also took my travel journal out of my backpack and began to write down what was happening. At 3:59 p.m. I wrote “awaiting deportation from Cuba.” I also noted a young male customs employee about 20 minutes earlier walked me upstairs to the departures lounge and allowed me to buy bottles of water and a coffee with Cuban pesos I had from my last trip to the country earlier this year. I wrote in my journal he told me, “I don’t like politics when (we) talked about Trump.” I bought an extra bottle of water for the Angolan man who was sitting next to me downstairs and gave him some of the cookies and dried fruit and nuts I had with me.

The air conditioning was not very strong and it was 90 degrees outside, but I was otherwise comfortable over the next two hours as I waited for my flight back to Miami. At around 6:30 p.m. the customs manager called me over to an elevator. She gave me back my passport and iPhone, handed me my boarding pass and escorted me to the gate. She handed my passport and boarding pass to a gate agent and told a male airport employee to escort me onto the plane. The customs manager said thank you to me as I entered the jet way.

I was the first person to board the plane, which made me feel extremely self-conscious because I was escorted past a group of elderly people in wheelchairs who would have normally boarded well before a 37-year-old man with no health and/or mobility issues. The person who escorted me onto the plane told me before I left customs that American had upgraded me to business class. I sat down in my seat and thought to myself, “Did this really just happen to me?”

I called my husband, Naff and my Havana contact and let them know I was about to leave Cuba. The onboard WiFi allowed me to connect to the Internet, write Facebook and Twitter posts about what happened and text contacts who were able to receive iMessages. I remained on the Internet during the safety demonstration video and take off that a thunderstorm south of the airport made extremely turbulent. The flight landed in Miami shortly after 8 p.m. and I was able to call my mother in New Hampshire and let my relatives know what had happened. A U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent in customs flagged me for a “hard” interview, but it turned out to be nothing more than a simple passport check. I cleared customs in less than 10 minutes and walked downstairs to baggage claim where I retrieved my suitcase that had been damaged. I reserved a rental car, drove to Miami Beach and arrived at a hotel on Collins Avenue I found online shortly after 9:30 p.m.

Coverage of LGBTI issues in Cuba will continue

I first traveled to Cuba in 2015 to cover government-approved IDAHOBiT events. Blade Photo Editor Michael Key and I in 2017 received press visas from the Cuban government that allowed us to cover that year’s IDAHOBiT commemorations in Havana as credentialed journalists. The Cuban government has also allowed me to enter the country with a “tourist card” three times — the most recent time on Feb. 28 — with no questions asked.

I have reported across Cuba over the last four years, from Santiago de Cuba in the east to Pinar del Rio in the west.

I have interviewed pro-government and independent activists and have become friends with many of them. I have interviewed vocal critics of the government in Cuba. I have published photo essays and recorded dozens of videos that document life on the island. I am also all too aware of the Cuban government’s human rights record and its treatment of journalists, regardless of who they may be or the credentials they may have.

Yariel Valdés González, a Blade contributor from Cuba, has asked for asylum in the U.S. because of the persecution he said he faced in his homeland because he is a journalist. The Cuban government blocked access to Tremenda Nota’s website on the island on the eve of the Feb. 24 referendum on a new constitution that once promised to extend marriage rights to same-sex couples. Authorities detained González in October 2016 as he was covering the aftermath of Hurricane Matthew in the city of Baracoa in eastern Cuba and again in September 2017 while reporting on preparations ahead of Hurricane Irma in his hometown of Sagua la Grande in Villa Clara province.

Authorities on Wednesday detained Luz Escobar, a reporter for 14ymedio, a website founded by Yoani Sánchez, a journalist who is a vocal critic of the Cuban government, for several hours after she tried to interview Havana residents who were displaced by a freak tornado that tore through parts of the city on Jan. 27. The contact in Havana with whom I had been speaking from customs told me about Escobar’s arrest after I boarded my flight to Miami. The U.S. Embassy in Havana also tweeted about it.

Notamos que @Luz_Cuba fue liberada. Muy buena noticia pero no deberia haber sido detenida, en primer lugar. #TodosSomosLuz #LibertadDePrensa #Cuba

— Embajada EE.UU. Cuba (@USEmbCuba) May 8, 2019

I tagged Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel and other government entities in a Tweet that asks for additional information about why I was prevented from entering the country. I have not received a response, and am not holding my breath for one.

Los funcionarios al Aeropuerto Internacional José Martí no me dieron ninguna explanación sobre la decisión del gobierno cubano de prevenirme de entrar el país. ¿Tienen información que pueden compartir conmigo? @CastroEspinM @DiazCanelB @CubaMINREX @USEmbCuba @EmbaCubaEEUU

— Michael K. Lavers (@mklavers81) May 9, 2019

I know there are increased concerns over an IDAHOBiT march that independent activists have said they plan to hold in Havana on Saturday. I know from Tremenda Nota and other independent Cuban media outlets the country’s economic situation has grown even more dire since I was last in Cuba less than three months ago. I also know President Trump last week threatened to impose a “full and complete embargo” and additional sanctions against Cuba over its continued support of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

The last two days have been quite surreal, and I continue to process what happened in Havana. I am quite uncomfortable with the fact that I find myself at the center of a story about a country for which I have a deep affection. I also want to avoid the politics and rhetoric over U.S. policy towards Cuba.

I am so incredibly fortunate to have had the opportunity to travel to Cuba over the last four years, to have had the chance to meet many of the island’s LGBTI activists and to have developed lifelong friendships. These feelings — and my commitment to continue my coverage of LGBTI issues in Cuba — have not changed.

Commentary

Blogging my way through the Norwegian Fjords and the Arctic

Celebrating Pride Norwegian style

Blog # 1 – Celebrity APEX cruise, Norwegian Fjords, and the Arctic

My travel agents, and friends, Dustin, and Scott, from My Lux Cruise, arranged for busses to pick us up from our London hotel, and head to Southampton, to board the Celebrity APEX. It rained on the two-hour trip from London, but stopped just as we got closer to Southampton, which seemed like a good omen. When I first sighted the ship, it was a little like coming home, as I traveled on the APEX before. The crew was welcoming as we got off the bus and check-in was easy. Within thirty minutes I was onboard and headed to my stateroom to drop off my hand baggage, and set up my computer. The only snag, as usual, was with corporate Celebrity, some of the things they promise aren’t there, and you have to make calls onboard to get them. One was the hypoallergenic bedding; I am allergic to feathers; the other was my WIFI was set so I couldn’t use both my phone and computer at the same time. The crew on board acted quickly to remedy both issues. I met my stateroom attendant Mylene, who is great, and she dealt with the bedding. As to WIFI, it works great thus far, and while I hate to credit Elon Musk for anything, Celebrity does have a contract with Starlink.

I walked around the ship until it was time to head to the sailaway party in the Iconic suite, hosted by Scott and Dustin. It was a great party, and the best part was seeing friends who I hadn’t seen in years. Ewan and Barry, who I first met on a cruise on the Celebrity Silhouette, about ten years ago, were there, actually on their honeymoon. We told each other we hadn’t changed in the ensuing years. As long as there is no mirror around for me to look into, I like to believe that. It was fun to reconnect with so many old and new friends who I would be spending the next twelve days with.

I then headed back to my stateroom, my luggage had arrived, and I could unpack. I am in the Retreat, the fancy part of ship, and have what is called a sky suite. That is a misnomer as it is basically just a little bigger stateroom, but very nice. I am on deck 10. My next stop was the LGBTQIA+ happy hour, which is how it is now listed in the daily program, at 6:00pm every evening in the EDEN bar. It was fun, and I met some more new friends. From there on to dinner with Rob and Carlos, my traveling companions, and others. We went to Normandie restaurant, one of four main dining rooms. Rob, acting like he always does, as a travel agent, had planned the daily schedule for this trip. He does a spreadsheet and emails it to all who are traveling with him, allowing the rest of us to not think at all, lol. While in the Retreat, I get the feeling I won’t be eating in the Retreat restaurant, Laminae, very often. Rather in one of the four main dining rooms, or the specialty restaurants, where we will eat at least five of our dinners.

The biggest surprise of the day occurred after dinner when walking around the ship. I saw the Captain sitting with some of the crew opposite Café al Bacio. As I walked over to introduce myself, saw he was chatting with a couple, so just stood nearby and waited. He looked up, and then shocked me by saying to them, oh there is the gentleman who interviewed me, and got me all that free publicity. I couldn’t believe he remembered me from when I did that interview during a transatlantic cruise in 2022. That was before the Celebrity PR department became too difficult and incompetent to deal with. We had a nice chat and told him literally thousands have seen and enjoyed reading about him. Then it was off to bed and a good night’s sleep to prepare for Brugge, Belgium, our first stop, the next morning.

Day 2 dawned beautiful. I had last been to Brugge in the 1970s and it was very much the same in so many good ways. We left the ship for an hour drive into town at about 8:45 and returned at 2:00pm. We had a great guide and walked for a few hours around the city where he regaled us with fun stories. We then had an hour on our own and I managed to get a wonderful Belgian waffle with strawberries, and Rob and Carlos each had Belgian fries and a beer. Then a stop to buy some Belgian chocolate. and back to the ship. I toured the gym, but didn’t work out, figured I would start the next morning when we were scheduled for a sea day. Then a totally relaxed afternoon and the 6:00pm LGBTQIA+ happy hour at EDEN. Then to the Tucson dining room for dinner. After dinner a few of us went to the theater and found it packed to the rafters. They were all there to hear Tabitha, a singer, who to my pleasant surprise, was really great. Her show was a tribute to iconic female songwriters. She also allowed the Celebrity Orchestra to shine, and they are incredible. Then back to my stateroom round 11pm, feeling really good about my 1st full day on the APEX.

Blog # 2 – Celebrity APEX cruise, Norwegian Fjords, and the Arctic

The second full day on Celebrity APEX dawned clear and sunny, and much warmer than anticipated. It was a day at sea. I had breakfast delivered to the stateroom; coffee, juice, fruit, and what they call a bagel. You eat it in two bites. I began the day, Sunday, finishing up my regular Blade columns, and then at 10am headed to the gym. There has to be some sort of penance for all I am eating. My lifecycle was waiting, and even some weights. Then off to the Retreat lounge for a cappuccino. A gaggle of my fellow cruisers were already there, and we spent the next couple of hours chatting, mostly politics, with friends not from the US who none-the-less shared my view of the felon in the White House. Then it was time for lunch, yes more food, and I met some of the gang in the Oceanview Café, the buffet. Again, a little bit of politics in the discussion, how can one not talk about the Trump/Musk feud. I don’t think the couple sitting next to us was totally happy with our conversation, but other than rolling their eyes a few times, they didn’t say anything. So far, I have seen no MAGA hats on the ship.

It got warm enough in the afternoon for people to head to the pool, not to swim, though a couple actually did, but most to sit in the loungers and enjoy the sun. We had been prepared for rain so this was great. The afternoon went by quicky and it was time for the LGBTQIA+ happy hour in the EDEN lounge. This was going to be every evening at 6:00pm and is listed in the daily program. Then we headed to the theater for the 7:30 show, Crystalize, a production show I had seen on another cruise. It was really good. From there it was off to the EDEN restaurant, which I believe is the best specialty restaurant on the ship. I had dinner with Rob and Carlos, and John and Paul who had recently moved from NY to Palm Springs. John and I talked a little about the New York Mayor’s race as he still has an apartment there and votes in New York. Turns out I am supporting Cuomo and he is not. Dinner didn’t disappoint; it was a grand two-hour feast. What was noticeable from the windows in EDEN was at 10:45 pm it was still light outside.

After a little walk around the ship time to head back to my stateroom. Day three would begin bright, yes very bright, and early, with my alarm going off at 6 am when coffee and a banana was delivered to the room. I was due in the Retreat lounge to meet friends and get off the ship by 7:30 am. We were approaching Flam, our first stop in Norway.

As I opened the blackout curtains in my stateroom, the view of the first Fjord we entered was breathtaking. It is why I was on this cruise and it’s meeting all my expectations for beauty. Instead of the predicted rain it was sunny, and warm enough to open my balcony door and take pictures. We left the ship and headed to the train station, a short walk, for the ride from Flam to Myrdal, about a one-hour trip up the mountain with breathtaking scenery. Countless waterfalls along the way. Again, it surpassed all my expectations and the beautiful weather held out just until we arrived back at the ship, about three hours later, when it began to rain lightly.

Back on the ship I headed to the gym, totally empty, and got ready for another sail away party in Dustin and Scott’s Iconic suite. This time a number of the senior crew were there including the Cruise Director, and Hotel Director. The Hotel Director I had met on a previous cruise and we chatted awhile. The Cruise Director is an interesting and very nice guy. He and his husband live in Las Vegas and he has been doing this with Celebrity for many years. He is a little older than most of the cruise directors I met before. It is a tough job. Then another lazy evening, first happy hour, then, Scott, Mike, Ken, Paul, John, and Paul, Rob, and Carlos, joined me for dinner at Normandie. After dinner we all went our separate ways. I headed to the show in the EDEN lounge. I was looking forward to seeing

Kyrylo and Yaroslav, the Ukrainian aerialists I had interviewed and written about on a previous cruise. I got a chance to say hello to them before the show began, and they are better than ever, and exciting to watch. The entire cast is incredible. Then back to my stateroom for a good night’s sleep. Day four was another sea day. At 2 pm we would be crossing into the Arctic Circle.

BLOG # 3 Celebrity APEX; Norwegian Fjords and the Arctic

Day five was as sea. Woke up to another beautiful day and this just seemed to be too good to be true. All the rain, and cold weather we anticipated, was nowhere in sight. Our luck was holding. This was going to be a totally lazy day on the ship, the kind I love. Breakfast was delivered to the room at 7:30 and then some writing and the gym. It was nearly empty again, which was great, no wait for the lifecycle.

There were a few guys from my traveling group there. From the gym it was over to the Retreat lounge, which is on the same deck, to get my cappuccino so I could really start my day the way I like. My friend Sid, from Carmel, was there, and we go to chat a little. He was going to play Rummikub with Janie and Will. I had my kindle with me and read for a while. There was going to be another party in Scott and Dustin’s Iconic suite as we entered the Arctic circle. The Captain announced he was going to host a pool party to celebrate and he and other senior officers would jump into the pool, and you could have your nose painted blue, in honor of crossing into the Arctic Circle. I did neither, jump into the pool or get the blue nose, but enjoyed watching the Captain come out of the pool in full uniform. A few of the guests actually went into the pool as well and the few that did had on bathing suits, always a few crazies on board, lol. They are the ones who do the polar plunges at home.

Then on my schedule for the day was the LGBTQ happy hour at 6:00pm and dinner reservations at Fine Cut, the steakhouse at 8:30pm. The meal was ok but can’t compare with EDEN as far as I am concerned. The filet mignon at EDEN was much better than the one at the steakhouse. There were a couple of other issues and when the nice lady came to the table asking if everything was ok, I let loose with my complaints. Told her it wasn’t her fault but hoped she would pass them along to the chef. She stopped by later and told me they would refund the money I paid for the dinner as it was one of my specialty restaurant dinners, you pay extra for those. I thought that was nice and thanked her. Tried to get the whole table comped but she wouldn’t go for that. After dinner I headed to the show in the Eden Lounge, a really good violinist. Then it was off to bed.

Day six we arrived in Tromso, often referred to as the Arctic’s capital. It is located above the Arctic Circle. We didn’t have a tour planned, but Celebrity said they would have shuttle busses available to take you into town. Problem was 1,000 passengers, and eight busses. The lines were ridiculous. So, a few of us hopped a taxi and headed to town. We had a nice taxi driver who asked us what port we had been to last and when we told him Flam, he said “oh you could go home now, Tromso is boring compared to Flam.” He wasn’t all wrong, but we enjoyed walking around town, and went to the Polar Museum, and my friends did some shopping. We got a kick out of the names of some places like “The Bastard Bar” and “The Misfit Bar.” There was also a Burger King and a 7 Eleven, just to make us feel at home. We walked around for a couple of hours and then did get a shuttle bus back. We had met David and Kate, and Kate and I headed to the shuttle bus stop where we saw Scott was also waiting. There was a long line but Scott told us as Retreat guests we could jump the line, so we did. Just as we were heading back to the ship it started to drizzle, again, the timing was great.

Then off to another happy hour and there was a show many of wanted to see at The Club that evening. It was Caravan, with the EDEN production cast, which included Kyrylo and Yaroslav, the Ukrainian gymnasts, and aerialists. Scott and Dustin had their butler get us into The Club first, for front row seats. The show was great. The full cast is amazingly talented. Then we had a late dinner in Normandie. Another tough day on board the APEX. Tomorrow we were off to Honningsvag. It would be a later start to the day which was great.

Blog # 4 Celebrity APEX cruise, Norwegian Fjords, and the Arctic

Day 7 dawned sunny, and much warmer than we anticipated. They told us Norway was having a heat wave. We were in Honningsvag, the northernmost city in mainland Europe. There were brightly painted wooden buildings, breathtaking fjords, and loads of waterfalls. The entire town had been rebuilt after World War II. We had twenty-four hours of sun; the sun doesn’t set here in the summer. We had a tour which took us to North Cape, for some incredible views, and interesting exhibits of the history of the area. It included information on how the King of Thailand had come to visit. There was an interesting installation, from a distance you could think it was a mini-Stonehenge, that was based on, and designed, by some children from around the world who visited in 1988. Then back to the ship for another relaxed evening. This time I headed to the theater for the 7:30 show, Tree of Life. A show I had seen before on another cruise, but worth seeing again. The casts of all the shows on board are incredibly talented. The dancers, singers, and aerialists, all make an evening in the theater exciting. What is great about the EDGE class ships main theater is the stage, with its risers and turntable, and the digital screens they have. Then dinner after the show. While I tend to head to bed early, there are many in my group, who keep going until late in the evening. The casino, the Martini Bar, and a host of other venues, go late into the night.

Day 8 was another day at sea. We cruised around the Arctic circle and then headed toward Geiranger, Norway. Once again, Sea days for me are always wonderful lazy days. That is the reason why I enjoy my annual transatlantic cruises. This years will begin in Rome on Halloween. The thirteen days back to Ft. Lauderdale. I had my usual breakfast in the room, then writing, then the gym, then the Retreat lounge for my cappuccino, and half the day is already gone. The evening included the LGBTQ happy hour, a show, and dinner. The only real decision to make is; dinner first and then the show, or the other way around.

Then often a late show in either EDEN or THE Club. On this day it was the Barricade Boys in the main theater, before dinner. They are good but the audio wasn’t, so the orchestra and the singers seemed to be competing. Then it was dinner and a late show in EDEN with my favorite cast of course including Kyrylo and Yaroslav.

Day 9 we arrived in Geiranger. It is an amazing city with a richly deserved designation as a UNESCO world heritage site. Once again blessed with incredible weather, we all took pictures as the Captain stopped the ship as we passed what are called the seven sister waterfalls in the Geiranger Fjord. Beautiful site to see. We learned 97% of the energy used on Geiranger comes from harnessing the power of all the waterfalls around the Island. They told us that by 2032 they hope to ban all fossil fuel using ships. They hope by that time there will be some electric ships, as Geiranger has a permanent population of less than 200, and last year there were nearly one million visitors.

We went on an excursion high up in the mountains with incredible vistas and lots of snow. Then we walked around the town. It was really a perfect visit. Then back to the ship for another evening of food, drink, music, and good company. What more could anyone ask. Life really is good. Some of us talked about just a twinge of guilt knowing the felon in the White House was making life intolerable for many, yet here we were. But we all agreed if we were to stop living our best lives in protest, he would win.

Day 10 and we were in Alesund. It was nearly seventy degrees, and sunny. The town was alight with gay flags. We were told there would be a PRIDE parade and festival starting at 2pm. So, it was off to our morning excursions which for me was to Alnes and some other fishing villages. We stopped at a beautiful historic church and once again the views everywhere we went were fantastic. At one stop we were treated to coffee and some chocolate cake. I struck up a conversation with a young man working there who was a high school senior. His name was Samuel, and he was hoping to go to university in the United States if the felon doesn’t mess up his plans. He wants to be a film director and go to school in California. He does have a good connection through one of his teachers who is friends with the director of Troll, now on Netflix.

When we got back to the center of town it was time for the Pride parade. It was just great to see so many young families and little kids waving gay flags. I met a family from Atlanta who were traveling through Norway and just happened to be here on this day for the parade. They had their kids with them, one a senior in high school, who is gay. They were fun to chat with. Then there were the sailors ready to march, and they had come from the military ship we had seen in the harbor. All-in-all the town was dressed in PRIDE colors, and it was so wonderful to see. That night back on the ship the cruise director had planned a PRIDE party in The Club. It was fun. Another incredible day in Norway, and on the Celebrity APEX.

BLOG # 5 Celebrity APEX; Norwegian Fjords and the Arctic

Day 11 dawned sunny and warm, but very windy. We were in Haugesund, our last stop in Norway. It is a bigger city, located between mountains, islands, and the North Sea. It is a cultural center for Norway. Our excursion was to the lighthouse, the second one we went to see. It was interesting but many of us felt Celebrity didn’t explain the excursion correctly on their website. Rather than a walk, it was more like a hike, on a very hilly gravel path. Again, we were lucky the weather was great, or it would have been a lot more uncomfortable for anyone with bad knees (me) or those walking with a cane as some on the excursion were. It was a far distance to the lighthouse from where the bus dropped us off. Our guide indicated he didn’t think Celebrity wrote about this fairly, and hoped everyone could make the trek. We all did, and saw some goats and beautiful scenery on the way. But when we got to the lighthouse it was disappointing. You couldn’t go inside and they had us in a nice room in one of the other buildings on the site. It had some beautiful artwork which was for sale, and they served us a tasty waffle and coffee, which I guess was to make up for the hike. I would not recommend this excursion to anyone. When we got back to the ship we drove through the town and realized it was Sunday, and nearly every shop was closed. A little disappointing for the last day in Norway. But each day on the cruise had been incredibly exciting so this was only a minor thing. There was a long line when we got back to the ship, but we realized it wasn’t to reboard, but rather everyone who had bought anything during the cruise was reclaiming their VAT tax. Our friends Nancy and Mary got on line. I kidded Nancy she shouldn’t have bought all those diamonds.

The rest of the day on the ship was great. I stopped for lunch at Café al Bacio and then there was a 5:30 party with the senior officers in the Eden Lounge. After that I stayed for the LGBTQ happy hour and arranged to have dinner with David and Kate at the Retreat restaurant, Luminae. It was the first time I would eat there on this cruise. But first we went to see the show in the main theater. They had a few of the people who had individual shows during the cruise, and it was nice. Then off to dinner where we bumped into Sid and Will and they joined us. After eating a quick, very fattening, dessert, I excused myself and went to The Club for a reprise of ‘Caravan’ with the Eden production cast. I was surprised the place wasn’t packed, and this time got a seat up front even without using the amazing Scott’s influence. I enjoyed the show as much the second time. It was the last time I could see Kyrylo and Yaroslav on this cruise. I then headed to the casino for the first time and lost a couple of pennies from my account. Literally only a couple of pennies, and with my friend Jake’s help cashed out the rest. Then it was back to the stateroom for a good night’s sleep. Tomorrow would be our final sea day as we head back to Southampton.

Day 12 showed we were no longer in 20 hours of sun. I woke up during the night and it was actually dark. It dawned sunny, but chillier. The sea was still smooth which was great. My last breakfast was delivered to the room; I will miss this when I get home. Then did some writing and headed to the gym. My last day of sitting on a Lifecyle and looking out at the beautiful sea. My next time on the Lifecyle would be back at the JCC, and I would be looking at a blank wall. Good thing I can read my kindle while peddling away. After the gym I went to the Retreat lounge, something you all would have guessed by now if you had read the previous blogs from any of my cruises. Met Terry and Andy there, and they were about to head to the gym. While at the gym I had bumped into Phil, the dance captain of the Eden production cast, and we agreed to meet at Café al Bacio at 3pm to chat. I may be doing a column on him at some point.

My evening plans included going to the final LGBTQ happy hour at EDEN, where Jill would be taking a group photo. Then heading to see ‘Rockumentary,’ the show at the theater with the full production cast. Then it’s dinner at Fine Cut Steakhouse, (hope it is better than the first time), with Rob and Carlos and Paul and John. I packed before I went to the happy hour. Our suitcases had to be outside our cabins by 10pm.

Day 13 and back in Southampton. I hadn’t slept all that well and the bonus to that was seeing a beautiful sunrise. Celebrity had arranged my transfer back to Heathrow airport for my flight back home and all that went on tine. It was the end of an amazing twelve days at sea, with great friends and absolutely awe-inspiring scenery. The Norwegian Fjords and the Arctic met all my expectations. Now I can look forward to my next transatlantic cruise leaving from Rome the end of October. If you have gotten this far, thanks so much for reading, and being a part of this amazing experience.

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist. He writes regularly for the Blade.

Commentary

I am a proud Jewish, gay man

My heart breaks for the two Israeli diplomats killed on the streets of D.C.

Antisemitism, racism, and Islamophobia, are terrible things to have to deal with, and we must all always speak out and reject them. But the reality is, as a proud, Jewish, gay man, living in Washington, D.C. today, I am more afraid of Donald ‘felon’ Trump, his Nazi sympathizing co-president Elon Musk, his own Joseph Goebbels, Stephen Miller; and his Cabinet flunkies like Homeland Security’s Kristi Noem and State Department’s Marco Rubio, than I am of any legal college demonstration. Mind you, I say legal.

We live in a world where Trump has made all kinds of outrageous behavior acceptable. He has dined with white nationalists, said there are fine people on both sides in his first comments when the Charlottesville riots occurred. Today, Trump sits with terrorists in Qatar, accepting a plane as a bribe, and negotiates with terrorists like Hamas. This is the world Donald Trump has created. That is what I fear the most. It is a world where Donald Trump has made it acceptable for racists, homophobes, sexists, antisemites, and Islamophobes to spout their hate in the public square.

This past year I published my memoir, and wrote about being a first generation American. My parents came here to escape the Nazis — my father from Germany, and my mother from Austria. My father joined the American Army and went back to fight the Germans. His parents were gassed in Auschwitz. I understood from them and their friends, what antisemitism was. But I grew up in a Jewish community in New York City, and as I wrote in my book, never felt any of it myself until I was 13 on a trip through the Midwest and was called a ‘Kike’ and had to ask someone what that meant.

As to being gay, I knew I was, even though I didn’t understand it, when I was 12. I could, and did hide that, until I was 34. I then came out in D.C., which turned out to be an easy place to come out. But it was near the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and that made you very careful. You were told not to have your insurance company pay for a blood test, so God forbid, people would think you were gay, or worse if you did test positive. There was rampant discrimination and fear regarding HIV/AIDS at the time. I know I lost at least two jobs because I was gay, yet luckily, neither of those impacted my career in the long run. I became a gay activist, fought for my community, and things got better. I had worked for Rep. Bella Abzug (D-N.Y.), sponsor of the first Equality Act, before I came out, and met many gay people who were very supportive and became lifelong friends.

Today, Donald Trump, literally through his actions, threatens the lives of trans persons. While we are celebrating WorldPride in D.C., which as a city is a very welcoming place for the LGBTQ community, countries around the globe have told their citizens to be on alert if they come here. The United States is on their watch list for unsafe travel because of Trump’s actions.

When Donald Trump was elected the first time, his racism, homophobia, sexism, and Islamophobia immediately came to the fore. It had a negative impact on the culture in our country. It actually changed the culture, and that, and he, have only gotten worse over time. Today, Trump and his MAGA minions, are truly frightening. Again, trans people are afraid and antisemitism and Islamophobia are rampant in our nation.

Trump tries to blame it on some foreign students, but reality is, it is his doing. He and his MAGA cult. They are the ones I fear, not a graduate student at Columbia who supports Palestinians. It is the Netanyahu government in Israel that is making things worse. Yes, Hamas must be defeated as they promote genocide against the Jewish people in Israel. But the Israeli government starving millions of Palestinian people in Gaza, who are not Hamas, is not helping anyone. It simply creates more antisemitism. Trump going back and forth on his support of Netanyahu, and then saying he wants to displace every Palestinian from their home in Gaza to build a resort, creates more antisemitism. Trump is the guilty one, not the Columbia student who speaks out for his Palestinian family.

Where this will end, I do not know. But my heart breaks for the two innocent Israeli diplomats recently killed on the streets of D.C. by a terrorist who basically was given permission to act out by what Trump is doing in the world. What he did was vile, and he should end up in jail for the rest of his life. Everyone needs to speak out every day, and say antisemitism is unacceptable, and must be stopped. I never want to see Germany in 1939 replicated here. But that is what Trump and his MAGA cult are doing. They threaten everyone who they disagree with, and seek vengeance for suspected slights. They are literally trying to destroy our democracy. By what they are doing they give the terrorist who ended the lives of that beautiful young Jewish couple in D.C., implicit permission to act. Because if a president can act like a criminal, why can’t he?

Commentary

‘A New Alliance for a New Millenium, 2003-2020’

Revisiting the history of gay Pride in Washington

In conjunction with WorldPride 2025, the Rainbow History Project is creating an exhibit on the evolution of Pride: “Pickets, Protests, and Parades: The History of Gay Pride in Washington.” It will be on Freedom Plaza from May 17-July 7. This is the ninth in a series of 10 articles that share the research themes and invite public participation. In “A New Alliance for a New Millenium” we discuss how Whitman-Walker’s stewardship of Pride led to the creation of the Capital Pride Alliance and how the 1960s demands of the Mattachine Society of Washington were seen as major victories under the Obama administration.

This section of the exhibit explores how the Whitman-Walker Clinic, a cornerstone of the community since the 1970s, stepped up to rescue Pride from a serious financial crisis. The Clinic not only stabilized Pride but also helped it expand, guiding the festival through its 30th anniversary and cementing its role as a unifying force for the city’s LGBTQ population. As Whitman-Walker shifted its focus to primary healthcare, rebranding as Whitman-Walker Health, a new era began with the formation of the Capital Pride Alliance (CPA). Born from the volunteers and community partners who had kept Pride going, CPA took the reins and transformed Capital Pride into one of the largest free LGBTQ festivals in the country. Under CPA’s stewardship, the festival grew to attract hundreds of thousands, with multi-day celebrations, headline performers, and a vibrant parade.

This period saw Pride become a true cross-section of the community, as former Capital Pride Alliance executive director Dyana Mason recalled: “It was wonderfully diverse and had a true cross section of our community… Everybody was there and just being themselves.” The festival’s expansion created space for more people to find a sense of belonging and affirmation. This growth was made possible through the support of sponsors, volunteers, and a city eager to celebrate-but it also sparked ongoing debates about the role of corporate funding and the meaning of Pride in a changing world.

National politics are woven throughout this era. In a powerful moment of recognition, Frank Kameny — the architect of D.C.’s first White House picket for gay rights and a founder of the Mattachine Society — was invited to the White House in 2009. There, President Obama and the U.S. government formally apologized for Kameny’s firing from federal service in 1957, a symbolic act that echoed the earliest demands of DC’s own Mattachine Society, the city’s first gay civil rights organization founded in 1961. The 2009 National Equality March revived the spirit of earlier mass mobilizations, linking LGBTQ rights to broader movements for social justice. The 2010s brought landmark victories: “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed, marriage equality became law. These wins suggested decades of protest had borne fruit, yet new generations continued to debate the meaning of true liberation and inclusion.

Our exhibit examines how the political edge of Pride has softened as the event has grown. As the festival expanded in scale and visibility, the focus on protest and activism has sometimes faded into the background, even as new challenges and divisions have emerged. Some voices have called for a return to Pride’s more radical roots. The 2017 Equality March for Unity and Pride drew 80,000 people to D.C., centering intersectional struggles — police violence, immigrant rights, trans inclusion — and exposing the widening rift between mainstream LGBTQ progress and the lived realities of the most vulnerable. The question remains: Are LGBTQ officers marching in uniform a sign of progress or a painful reminder of Pride’s roots in resistance to state violence? During Capital Pride 2017, activists blocked the parade, targeting floats sponsored by corporations linked to weapons manufacturing, pipeline financing, and other forms of oppression.

As we prepare for WorldPride and the anniversaries of D.C.’s first Gay Pride Day Block Party and the White House picket, the Rainbow History Project invites you to experience this living history at Freedom Plaza. Through archival images and the voices of organizers and participants, you’ll discover how Pride in DC has been shaped by resilience, reinvention, and the ongoing struggle to ensure every voice is heard.

Zoey O’Donnell is a member of the Rainbow History Project. Vincent Slatt is RHP’s senior curator.

-

U.S. Supreme Court4 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court4 days agoSupreme Court to consider bans on trans athletes in school sports

-

Out & About4 days ago

Out & About4 days agoCelebrate the Fourth of July the gay way!

-

Virginia4 days ago

Virginia4 days agoVa. court allows conversion therapy despite law banning it

-

Opinions4 days ago

Opinions4 days agoCan we still celebrate Fourth of July this year?