Books

FALL ARTS 2018 BOOKS: rans themes front and center in many fall ’18 books

‘Black Queer Hoe,’ ‘Rise of Genderqueer’ among anticipated titles

‘Black Queer Hoe,’ ‘Rise of Genderqueer’ among anticipated titles for 2018.

EVENTS

The 23rd annual Baltimore Book Festival takes place at Baltimore’s Inner Harbor Sept. 28-30 from 11 a.m.-7 p.m. The festival will feature hundreds of local and national authors speaking on 11 stages throughout the festival, including several LGBT contributors.

On Saturday (Sept. 29) at 3 p.m. at the Radical Bookfair Pavilion, Charlene A. Carruthers, a black queer feminist activist and author, presents her new book “Unapologetic: A Black, Queer and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements,” exploring how (and why) to make the black liberation movement more radical, queer and feminist. Later that day at 5 p.m. at Science Fiction and Fantasy, a panel of LGBT authors will discuss the integration of queer folks in science fiction writing and the role queer voices play in the genre. The festival is free and open to the public. For more information, including a full schedule of events and a map, visit baltimorebookfestival.com.

This year’s Fall for the Book festival takes place Oct. 10-13 at George Mason University (10:30 a.m.-7:30 p.m.; 4400 University Dr., Fairfax, Va.). Now in its 20th year, the festival seeks to connect readers with authors and encourage cultural growth through reading.

In addition to nationally renowned politician and civil rights leader John Lewis, there are many noteworthy activists and authors lined up, including several representatives from the LGBT world. Sandy Allen, a non-binary trans writer, speaker and teacher, will participate in a panel on “Writing Through Identity” with three other essayists whose work all focus on exploration of identity (Oct. 12, 6-7:15 p.m.). Eithne Luibhéid, professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona, will also give a talk on “Sexualities, Intimacies and Queer Migration,” dissecting the intersection between immigration and queerness (Oct. 10, 4:30 p.m.). The event is free and open to the public. For more details and a full schedule of events, visit fallforthebook2018.org.

RELEASES

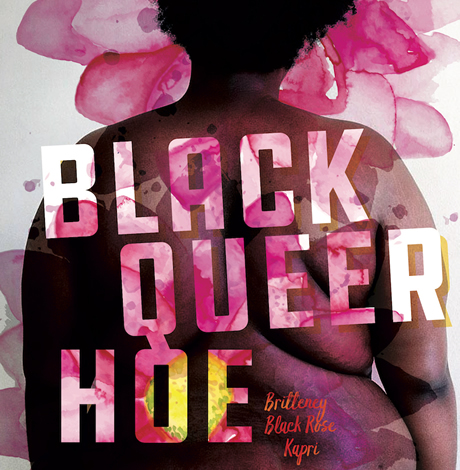

In her powerful debut, “Black Queer Hoe” (Haymarket Books, Sept. 4), Chicago performance poet and playwright Britteney Black Rose Kapri wrestles with questions about sexual freedom and sexual exploitation in a world where black queer women are frequently denied basic rights to bodily autonomy. Kapri is refreshingly unapologetic and provides crucial insights and perspective into many conversations currently playing out across the country surrounding race, gender, sexuality and power.

In his new poetry collection, “The Rise of Genderqueer” (Brain Mill Press, Sept. 4), Wren Hanks challenges assumptions about gender, dismantling the status quo from every angle. A trans writer from Texas, his poems are raw and authentic and create a space for his extraordinary voice.

Akemi Dawn Bowman’s new novel “Summer Bird Blue” (Simon Pulse, Sept. 11) tells the story of Rumi Seto, a mixed race teen suffering from the tragedy of losing her sister while simultaneously attempting to understand her own identity as asexual. A raw story about loss, grief and identity, “Summer Bird Blue” is a powerful read that sheds light on the strength and perseverance of humanity.

If you love graphic novels, Tillie Walden’s “On a Sunbeam” (First Second, Oct. 2) is a must read. Set in the deepest reaches of space, “On a Sunbeam” is an epic graphic novel that takes the reader on one girl’s journey of falling in love at boarding school then losing everything. A story of love and second chances, Walden beautifully writes and illustrates what one critic has called “her best work yet” in this fall’s release.

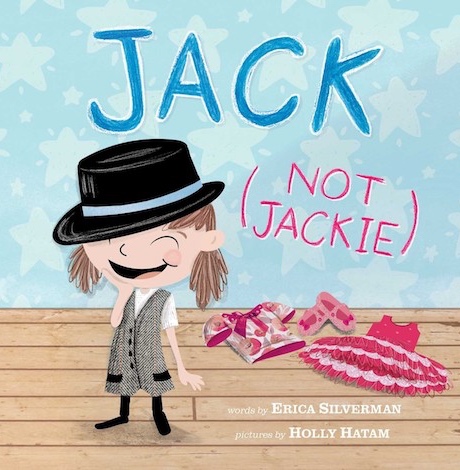

If you have a young person in your life, “Jack (Not Jackie)” (little bee books, Oct. 9) is a wonderful gift idea. In this moving picture book, Erica Silverman tells the story of a big sister who realizes her little sister Jackie may not in fact be her sister at all. Jackie doesn’t like to wear dresses or have long hair and wants to be called Jack instead.

Author of acclaimed fiction “Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda” Becky Albertalli alongside Adam Silvera release their new young-adult romance “What If It’s Us” this October (HarperTeen, Oct. 9). Ben has just broken up with his boyfriend when Arthur moves to New York City for the summer to work on Broadway. Although Ben is heartbroken and not interested in starting a new relationship, when he meets Arthur at the post office, he’s forced to reconsider. “What If It’s Us” is a story of fate and trying to figure out what exactly the universe has in store for us.

Lambda Award Winner Julia Watts releases her latest young-adult novel, “QUIVER” (Three Rooms Press, Oct. 16), this fall. Set in rural Tennessee, it tells of a friendship between two teenagers on opposite sides of today’s culture wars. Libby comes from a strict evangelical family while her new neighbor Zo is a gender fluid feminist, socialist (and of course vegetarian), and yet despite their differences, they are drawn to each other and connect instantly.

Creator of Amazon’s “Transparent” Jill Soloway is finally releasing her powerful memoir “She Wants It: Desire, Power and Toppling the Patriarchy” (Crown Archetype, Oct. 16), which reveals her personal journey from a straight, married mother of two to a queer and nonbinary activist. Her memoir deconstructs the harmful dominant narratives still shaping our society, challenging the status quo and encouraging the reader to think critically about issues from consent and #metoo to gender and inclusion.

If you love poetry, Mary Lambert’s new collection “Shame Is an Ocean I Swim Across” (Feiwel & Friends, Oct. 23) should definitely be added to your fall reading list. A writer and LGBT activist, Lambert is also a songwriter and collaborated with Macklemore and Ryan Lewis to create the Grammy-nominated queer anthem “Same Love.” The poems in her new collection tackle issues of sexual assault, mental illness and body acceptance.

In “The Autobiography of a Transgender Scientist” (Mit Press, Oct. 23) Ben Barres, esteemed neurobiologist at Stanford University, tells the story of his life from his gender transition to his scientific work and finally his advocacy for gender equity in the sciences. This book, completed shortly before his death in 2017, explores his experience as a female student at MIT in the 1970s and his transition from female to male in his 40s alongside fascinating accounts of his scientific accomplishments.

If you enjoyed “Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda,” Kheryn Callender’s new book “This is kind of an epic love story” (HarperCollins, Oct. 30) may be up your alley. After losing his father and watching too many relationships in his life fall apart, Nathan Bird no longer believes in happy endings. However all that changes when he realizes his true feelings for his best friend from childhood, Oliver. Can Nathan set aside his anxieties and pursue his own happy ending?

Set in Washington, Robin Talley’s “Pulp” (Harlequin Teen, Nov. 13) tells of two queer women across generations, one from the 1950s and another from present day. The first narrative follows 18-year-old Janet as she struggles to keep her queer identity a secret and finds solace in literature during the age of McCarthyism. The second follows Abby Zimet who can’t stop thinking about her senior project on 1950s lesbian pulp fiction and her ever-growing connection with the authors and works she’s reading. Talley’s dual narrative novel weaves the stories of two girls across six decades, connected by words, bravery and their desire to push society forward.

Trans activist Brynn Tannehill walks readers through transgender issues and dismantles harmful misconceptions in her new book “Everything you every wanted to know about trans* (but were too afraid to ask)” (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, Nov. 21). Her book will open your eyes and leave you prepared to engage in critical conversations around transgender folks and most importantly, be a better ally to the trans community.

In “Not just a tomboy: a trans masculine memoir” (Jessica Kingsley, Nov. 21), Caspar J. Baldwin recounts his own gender exploration from the 1990s to present day, arguing that even though progress has been made in the last two decades, there is still a lot of work to be done regarding trans activism and acceptance. This book serves as both a support for trans men currently struggling to accept their identities and live with their bodies and an informative glimpse for non-trans folks into one trans man’s experience.

This past year, you’ve often had to make do.

Saving money here, resources there, being inventive and innovative. It’s a talent you’ve honed, but isn’t it time to have the best? Yep, so grab these Ten Best of 2025 books for your new year pleasures.

Nonfiction

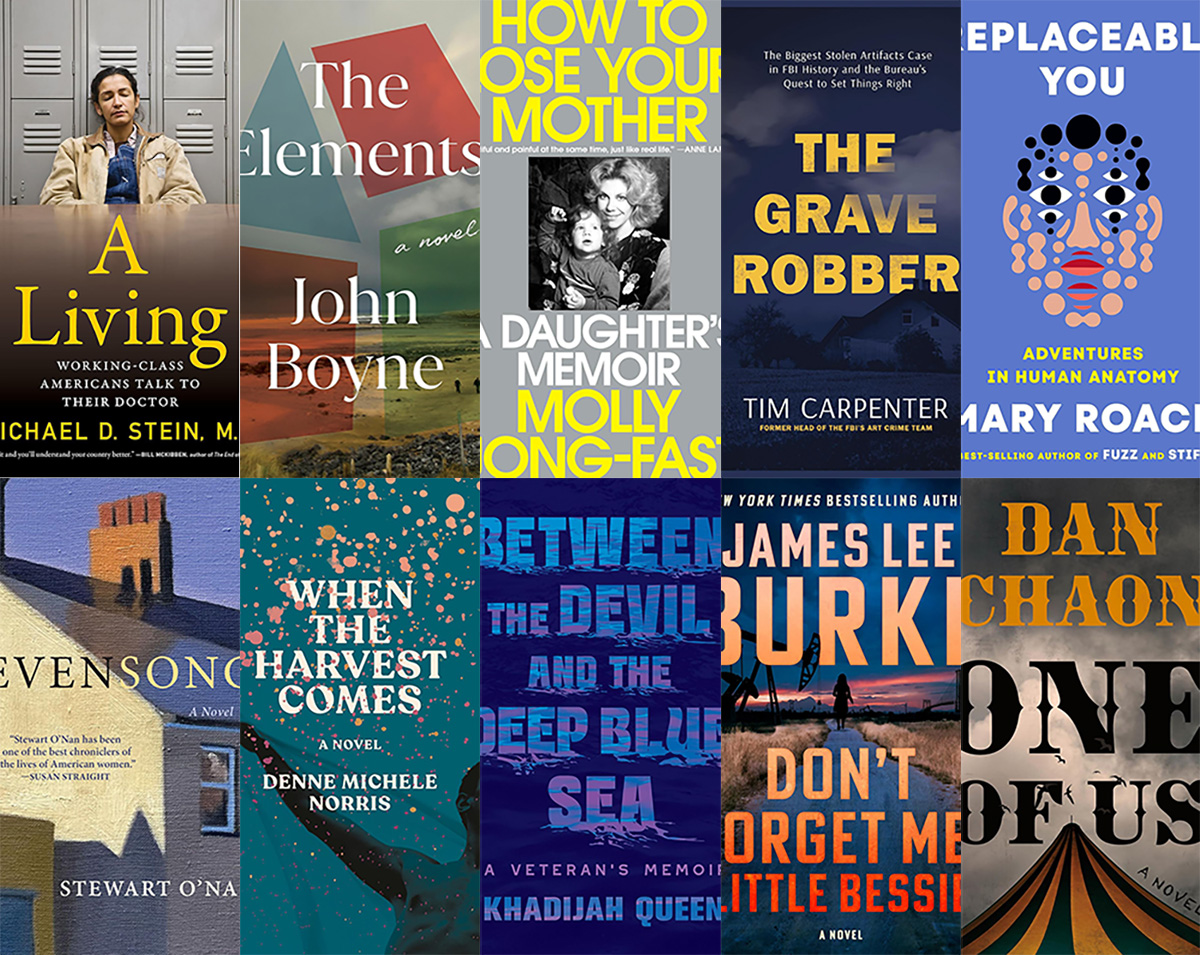

Health care is on everyone’s mind now, and “A Living: Working-Class Americans Talk to Their Doctor” by Michael D. Stein, M.D. (Melville House, $26.99) lets you peek into health care from the point of view of a doctor who treats “front-line workers” and those who experience poverty and homelessness. It’s shocking, an eye-opening book, a skinny, quick-to-read one that needs to be read now.

If you’ve been doing eldercare or caring for any loved one, then “How to Lose Your Mother: A Daughter’s Memoir” by Molly Jong-Fast (Viking, $28) needs to be in your plans for the coming year. It’s a memoir, but also a biography of Jong-Fast’s mother, Erica Jong, and the story of love, illness, and living through the chaos of serious disease with humor and grace. You’ll like this book especially if you were a fan of the author’s late mother.

Another memoir you can’t miss this year is “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: A Veteran’s Memoir” by Khadijah Queen (Legacy Lit, $30.00). It’s the story of one woman’s determination to get out of poverty and get an education, and to keep her head above water while she goes below water by joining the U.S. Navy. This is a story that will keep you glued to your seat, all the way through.

Self-improvement is something you might think about tackling in the new year, and “Replaceable You: Adventures in Human Anatomy” by Mary Roach (W.W. Norton & Company, $28.99) is a lighthearted – yet real and informative – look at the things inside and outside your body that can be replaced or changed. New nose job? Transplant, new dental work? Learn how you can become the Bionic Person in real life, and laugh while you’re doing it.

The science lover inside you will want to read “The Grave Robber: The Biggest Stolen Artifacts Case in FBI History and the Bureau’s Quest to Set Things Right” by Tim Carpenter (Harper Horizon, $29.99). A history lover will also want it, as will anyone with a craving for true crime, memoir, FBI procedural books, and travel books. It’s the story of a man who spent his life stealing objects from graves around the world, and an FBI agent’s obsession with securing the objects and returning them. It’s a fascinating read, with just a little bit of gruesome thrown in for fun.

Fiction

Speaking of a little bit of scariness, “Don’t Forget Me, Little Bessie” by James Lee Burke (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28) is the story of a girl named Bessie and her involvement with a cloven-hooved being who dogs her all her life. Set in still-wild south Texas, it’s a little bit western, part paranormal, and completely full of enjoyment.

“Evensong” by Stewart O’Nan (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28) is a layered novel of women’s friendships as they age together and support one another. The characters are warm and funny, there are a few times when your heart will sit in your throat, and you won’t be sorry you read it. It’s just plain irresistible.

If you need a dark tale for what’s left of a dark winter season, then “One of Us” by Dan Chaon (Henry Holt, $28), it it. It’s the story of twins who become orphaned when their Mama dies, ending up with a man who owns a traveling freak show, and who promises to care for them. But they can’t ever forget that a nefarious con man is looking for them; those kids can talk to one another without saying a word, and he’s going to make lots of money off them. This is a sharp, clever novel that fans of the “circus” genre shouldn’t miss.

“When the Harvest Comes” by Denne Michele Norris (Random House, $28) is a wonderful romance, a boy-meets-boy with a little spice and a lot of strife. Davis loves Everett but as their wedding day draws near, doubts begin to creep in. There’s homophobia on both sides of their families, and no small amount of racism. Beware that there’s some light explicitness in this book, but if you love a good love story, you’ll love this.

Another layered tale you’ll enjoy is “The Elements” by John Boyne (Henry Holt, $29.99), a twisty bunch of short stories that connect in a series of arcs that begin on an island near Dublin. It’s about love, death, revenge, and horror, a little like The Twilight Zone, but without the paranormal. You won’t want to put down, so be warned.

If you need more ideas, head to your local library or bookstore and ask the staff there for their favorite reads of 2025. They’ll fill your book bag and your new year with goodness.

Season’s readings!

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

This gay author sees dead people

‘Are You There Spirit? It’s Me, Travis’

By Travis Holp

c.2025, Spiegel and Grau

$28/240 pages

Your dad sent you a penny the other day, minted in his birth year.

They say pennies from heaven are a sign of some sort, and that makes sense: You’ve been thinking about him a lot lately. Some might scoff, but the idea that a lost loved one is trying to tell you he’s OK is comforting. So read the new book, “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis” by Travis Holp, and keep your eyes open.

Ever since he was a young boy growing up just outside Dayton, Ohio, Travis Holp wanted to be a writer. He also wanted to say that he was gay but his conservative parents believed his gayness was some sort of phase. That, and bullying made him hide who he was.

He also had to hide his nascent ability to communicate with people who had died, through an entity he calls “Spirit.” Eventually, though it left him with psychological scars and a drinking problem he’s since overcome, Holp was finally able to talk about his gayness and reveal his otherworldly ability.

Getting some people to believe that he speaks to the dead is still a tall order. Spirit helps naysayers, as well as Holp himself.

Spirit, he says, isn’t a person or an essence; Spirit is love. Spirit is a conduit of healing and energy, speaking through Holp in symbolic messages, feelings, and through synchronistic events. For example, Holp says coincidences are not coincidental; they’re ways for loved ones to convey messages of healing and energy.

To tap into your own healing Spirit, Holp says to trust yourself when you think you’ve received a healing message. Ignore your ego, but listen to your inner voice. Remember that Spirit won’t work on any fixed timeline, and its only purpose is to exist.

And keep in mind that “anything is possible because you are an unlimited being.”

You’re going to want very much to like “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis.” The cover photo of author Travis Holp will make you smile. Alas, what you’ll find in here is hard to read, not due to content but for lack of focus.

What’s inside this book is scattered and repetitious. Love, energy, healing, faith, and fear are words that are used often – so often, in fact, that many pages feel like they’ve been recycled, or like you’ve entered a time warp that moves you backward, page-wise. Yes, there are uplifting accounts of readings that Holp has done with clients here, and they’re exciting but there are too few of them. When you find them, you’ll love them. They may make you cry. They’re exactly what you need, if you grieve. Just not enough.

This isn’t a terrible book, but its audience might be narrow. It absolutely needs more stories, less sentiment; more tales, less transcendence and if that’s your aim, go elsewhere. But if your soul cries for comfort after loss, “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis” might still make sense.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

‘Dogs of Venice’ looks at love lost and rediscovered

A solo holiday trip to Italy takes unexpected turn

‘The Dogs of Venice’

By Steven Crowley

c.2025, G.P. Putnam & Sons

$20/65 pages

One person.

Two, 12, 20, you can still feel alone in a crowded room if it’s a place you don’t want to be. People say, though, that that’s no way to do the holidays; you’re supposed to Make Merry, even when your heart’s not in it. You’re supposed to feel happy, no matter what – even when, as in “The Dogs of Venice” by Steven Rowley, the Christmas tinsel seems tarnished.

Right up until the plane door closed, Paul held hope that Darren would decide to come on the vacation they’d planned for and saved for, for months.

Alas, Darren was a no-show, which was not really a surprise. Three weeks before the departure, he’d announced that their marriage wasn’t working for him anymore, and that he wanted a divorce. Paul had said he was going on the vacation anyhow. Why waste a perfectly good flight, or an already-booked B&B? He was going to Venice.

Darren just rolled his eyes.

Was that a metaphor for their entire marriage? Darren had always accused Paul of wanting too much. He indicated now that he felt stifled. Still, Darren’s unhappiness hit Paul broadside and so there was Paul, alone in a romantic Italian city, fighting with an espresso machine in a loft owned by someone who looked like a frozen-food spokeswoman.

He couldn’t speak or understand Italian very well. He didn’t know his way around, and he got lost often. But he felt anchored by a dog.

The dog – he liked to call it his dog – was a random stray, like so many others wandering around Venice unleashed, but this dog’s confidence and insouciant manner inspired Paul. If a dog could be like that, well, why couldn’t he?

He knew he wasn’t unlovable but solo holidays stunk and he hated his situation. Maybe the dog had a lesson to teach him: could you live a wonderful life without someone to watch out for, pet, and care for you?

Pick up “The Dogs of Venice,” and you might think to yourself that it won’t take long to read. At under 100 pages, you’d be right – which just gives you time to turn around and read it again. Because you’ll want to.

In the same way that you poke your tongue at a sore tooth, author Steven Rowley makes you want to remember what it’s like to be the victim of a dead romance. You can do it here safely because you simply know that Paul is too nice for it to last too long. No spoilers, though, except to say that this novel is about love – gone, resurrected, misdirected – and it unfolds in exactly the way you hope it will. All in a neat evening’s worth of reading. Perfect.

One thing to note: the Christmas setting is incidental and could just as well be any season, which means that this book is timely, no matter when you want it. So grab “The Dogs of Venice,” enjoy it twice with your book group, with your love, or read it alone.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

Sponsored4 days ago

Sponsored4 days agoSafer Ways to Pay for Online Performances and Queer Events

-

District of Columbia3 days ago

District of Columbia3 days agoTwo pioneering gay journalists to speak at Thursday event

-

Colombia3 days ago

Colombia3 days agoBlade travels to Colombia after U.S. forces seize Maduro in Venezuela

-

a&e features3 days ago

a&e features3 days agoQueer highlights of the 2026 Critics Choice Awards: Aunt Gladys, that ‘Heated Rivalry’ shoutout and more