Obituary

OBITUARY: Mike Ritter, Blade contributor, dies at 48

Award-winning cartoonist worked in LGBT media

Mike Ritter was a well-known, award-winning political cartoonist. (Photo by Michael Chesworth; courtesy GA Voice)

Mike Ritter, a Washington Blade contributor and art director for the LGBT newspaper GA Voice in Atlanta, died shortly after midnight on Sunday, March 30. He was 48.

He was admitted to the emergency room at Atlanta Medical Center on Friday, March 28, where doctors determined he had a dissection on his aorta, a severe condition. After undergoing a 10-hour surgery on Saturday, he died due to the severity of his condition and complications from undergoing open-heart surgery.

Ritter was a native of Washington State and attended college at Arizona State University. While working on the newspaper at ASU, Ritter was awarded 10 Gold Circle Awards from Columbia University’s Scholastic Press Association. He also won two first-place awards in the editorial cartoon and comic strip categories.

He was the editorial cartoonist at the Tribune in Phoenix from 1992-2005 and a syndicated cartoonist with King Features Syndicate.

Ritter was honored by the Suburban Newspapers of America while at the Tribune and was awarded first place for editorial cartooning by the Arizona Press Club in 1993, 1995 and 1996.

In 1999 he received the Thomson newspaper chain’s highest award for illustration and a Freedom of Information Award from the Arizona Newspaper Association.

He served as president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists from 2003-2004. The AAEC noted Ritter was likely one of the first openly gay staff cartoonist at a mainstream daily newspaper while he worked for the East Valley and Scottsdale Tribune papers in Arizona. The East Valley Tribune has a slide show of his nationally recognized 9-11 political cartoon as well as many of his illustrations.

In 2004 he was profiled by Editor & Publisher magazine where he was also noted for being an openly gay staff cartoonist at a mainstream daily newspaper.

After Ritter moved to Atlanta, he joined the staff of the former Southern Voice where he was a graphic designer and cartoonist. He also was a cartoonist for GA Voice and worked for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution before joining the GA Voice staff as full-time art director last year. In 2011 as cartoonist for the GA Voice, he won third place for Best Original Editorial Cartoon in the National Newspaper Association’s Better Newspaper contest. The cartoon was a biting look at the Atlanta Police Department’s raid on the Atlanta Eagle after news broke that that the lead investigator of the raid was arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol and marijuana. No drugs were found during the raid of the Eagle in 2009.

Many of his GA Voice and SoVo cartoons were picked up by other LGBT media outlets and blogs and he was an occasional Blade contributor, including work on several colorful and memorable front covers.

“Mike was a dear friend, a great person. He made me laugh. He made me think. He made me a better person and a better editor. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of old music and old movies. A true Renaissance man,” said Dyana Bagby, GA Voice editor. “He kept his great sense of humor until the very end even though he was in pain and uncomfortable. We at the GA Voice are heartbroken.”

Ritter’s impact goes far beyond his cartoons and graphic design, agreed Laura Douglas-Brown, GA Voice co-founder and former editor.

“I could talk about Mike’s brilliance, his skill as a cartoonist and illustrator, his keen political wit — but this would barely touch the surface of who Mike was to so many,” Douglas-Brown said. “There simply are no words big enough for the man he was or the legacy he leaves behind.”

His best friends, Will Alford and Tim Messier, are in contact with the family and plans for a memorial will be announced as soon as more information is made available.

He was born Aug. 21, 1965, and his family includes five older sisters, a brother and his parents.

Obituary

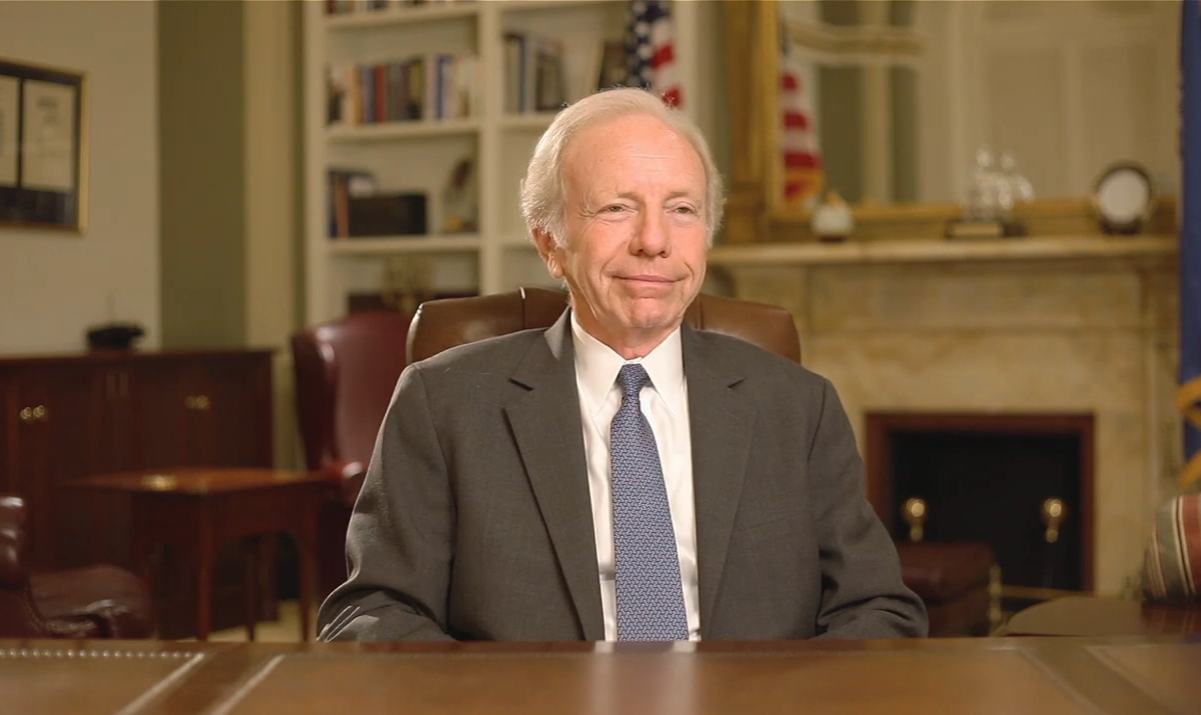

Joe Lieberman dies at 82

Former senator, vice presidential nominee championed ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ repeal

Former U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, who had served first as a longtime Democratic senator and then declared himself an independent winning reelection in 2006, died Wednesday at New York-Presbyterian Hospital due to complications from a fall. He was 82 years old.

The announcement of his death was released by Lieberman’s family and noted “his beloved wife, Hadassah, and members of his family were with him as he passed. Senator Lieberman’s love of God, his family and America endured throughout his life of service in the public interest.”

Lieberman, who nearly won the vice presidency on the Democratic ticket with former Vice President Al Gore in the disputed 2000 election and who almost became Republican John McCain’s running mate eight years later, viewed himself as a centrist Democrat, solidly in his party’s mainstream with his support of abortion rights, environmental protection, gay rights and gun control, the Washington Post reported.

The Post added that Lieberman was also unafraid to stray from Democratic orthodoxy, most notably in his consistently hawkish stands on foreign policy.

Lieberman was first elected to the U.S. Senate as a Democrat in 1988. He was also the first person of Jewish background or faith to run on a major party presidential ticket.

In 2009 he supported the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which was passed as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 on Oct. 22, 2009, and then was signed into law on the afternoon of Oct. 28 by then-President Barack Obama.

Lieberman, who served in the Senate for more than two decades, alongside with U.S. Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine), were the original co-sponsors of the legislation in the successful effort to repeal the Pentagon policy known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” which barred open service by gay and lesbian servicemembers in 2011.

Lieberman said the effort to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in Congress was one of the most satisfying and thrilling experiences he’s had as a senator.

“In our time, I think the front line of the civil rights movement is to protect people in our country from discrimination based on sexual orientation — all the more so when it comes to the United States military, whose mission is to protect our security so we can continue to enjoy the freedom and equal opportunity under law,” Lieberman said.

In an statement to the Washington Blade on Wednesday, Human Rights Campaign Vice President for Government Affairs David Stacy said:

“Senator Lieberman was not simply the lead Senate sponsor of the repeal of ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ — he was its champion, working tirelessly to allow lesbian, gay, and bisexual people to serve in the military as their authentic selves. The nation’s first Jewish vice presidential nominee, Lieberman had a historic career and his unwavering support for lesbian, gay and bisexual military servicemembers is a powerful legacy. Our hearts go out to his family and friends as they grieve a tremendous loss.”

In September 2011, during a press conference marking the repeal of the Pentagon policy, questions emerged about how to extend greater benefits to LGBTQ service members.

In addition to the legislation that would repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” reporters asked lawmakers about legislation in the Senate known as the Respect for Marriage Act which was aimed at the repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act, which prohibited same-sex marriage. Collins and Lieberman weren’t co-sponsors of that legislation.

Collins had left the news conference at the start of the question-and-answer period. In response to a question from the Blade, Lieberman offered qualified support for the Respect for Marriage Act.

The Connecticut senator said he had issues with the “full faith and credit” portion of the Respect for Marriage Act enabling federal benefits to flow to married gay couples even if they live in a state that doesn’t recognize same-sex marriage.

“I do support it in part — I think we’ve got to celebrate what we’ve done today — I certainly support it in regard to discrimination in federal law based on sexual orientation,” Lieberman said.

That issue became a mute point after June 26, 2015, when in a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, Obergefell v. Hodges, justices ruled that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Lieberman by that time however, had retired from the U.S. Senate. He announced he would not seek another term on Dec. 12, 2012, and left the Senate the following year. He was succeeded by Democratic Congressman Chris Murphy.

Following his retirement from the Senate, Lieberman moved to Riverdale in the Bronx and registered to vote in New York as a Democrat.

In 2024 Lieberman was leading the search to find a presidential candidate for the third-party group No Labels to run against former President Donald Trump and incumbent President Joe Biden, with whom he had served with in the Senate.

In a post on X (formerly Twitter) former President Barack Obama paid tribute to Lieberman:

“Joe Lieberman and I didn’t always see eye-to-eye, but he had an extraordinary career in public service, including four decades spent fighting for the people of Connecticut. He also worked hard to repeal “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” and helped us pass the Affordable Care Act. In both cases the politics were difficult, but he stuck to his principles because he knew it was the right thing to do. Michelle and I extend our deepest condolences to Hadassah and the Lieberman family.”

Joe Lieberman and I didn’t always see eye-to-eye, but he had an extraordinary career in public service, including four decades spent fighting for the people of Connecticut. He also worked hard to repeal “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” and helped us pass the Affordable Care Act. In both…

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) March 27, 2024

Lieberman’s funeral will be held on Friday at Congregation Agudath Sholom in his hometown of Stamford, Conn. An additional memorial service will be announced at a later date.

William Joseph “Bill” Troy passed away peacefully on Saturday, Jan. 13, 2024, at Cayuga Medical Center with his family at his bedside, from recent medical issues after living an active and robust life, according to a statement released by family. He was 69.

Troy was born April 15, 1955, in Elmira, N.Y. to William and Shirley Troy. He attended school in Ithaca and left to attend college at the University of Rochester. He worked at the university at various positions to help pay his way through, and he graduated in 1978 with a bachelor’s degree in history. He continued working at the university and living in Rochester until he accepted an internship in the federal offices of Congressman Matt McHugh of the NY 28th District from 1978-1983.

Troy was a life-long collector of various things, starting with coins and comics as a youngster, but in the 1980s he moved on to Art Deco lamps, disco records, antique furnishings, Arts & Crafts pottery, and a multitude of similar objects. He followed his passion of seeking antiques and used furnishings in Washington where he met many like-minded people and formed friendships with collectors and dealers.

Troy lived with his friend and partner Kirk Palmatier in Washington until December 2022 when he moved to Newark, N.Y., Palmatier’s hometown. He also wanted to enjoy his Ithaca family more by living nearer to them.

Troy is survived by five loving sisters and two loving brothers and several nieces and nephews. His death was preceded by that of his parents, William and Shirley Troy. Troy is also survived by his friend and partner Kirk Palmatier of Newark, N.Y., and a number of D.C.-area friends and business associates from over the past years. Arrangements to memorialize Troy will be with his family at a later date. In lieu of flowers, the family asks for donations to your favorite cancer or hospice organization.

Obituary

Longtime LGBTQ advocate ABilly S. Jones-Hennin dies at 81

Credited with advancing bisexual presence in the movement

ABilly S. Jones-Hennin, a longtime D.C. LGBTQ rights advocate who co-founded the National Coalition of Black Gays in 1978 and helped organize the first March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1979, died Jan. 19 at his and his husband’s winter home in Chetumal, Mexico.

His partner and husband of 45 years, Christopher Hennin, said the cause of death was complications associated with Parkinson’s Disease and advance stage spinal stenosis. He was 81.

Jones-Hennin, who identified as bisexual, is credited with advancing the presence of the bisexual community within the LGBTQ rights movement while working through several organizations he helped to form to advance of the overall cause of LGBTQ and African-American civil rights.

He was born in St. Johns, Antigua in 1942 and was adopted at the age of 3 by an American civil rights activist couple. According to biographical information on Jones-Hennin released by organizations he worked with, he grew up in South Carolina and Virginia. He served in the U.S. Marines after graduating from high school in Richmond before graduating from Virginia State University in 1967. He later received a master’s degree in social work at Howard University in D.C.

A biographical write-up on Jones-Hennin by the National Black Justice Coalition, an LGBTQ organization, says he was married to a woman for seven years and had three children before he and his wife separated. In a 2022 interview published by the AARP, Jones-Hennin said the separation came after he came out as gay before coming to the self-realization that he was in fact bisexual. He said he remained on good terms with his children and even took them to LGBTQ events.

Christopher Hennin said he and Jones-Hennin met in 1978 in D.C. while Jones-Hennin worked in accounting and management for different consulting firms, including the firm Macro International. At one point in the 1980s Jones-Hennin worked for D.C.’s Whitman-Walker Clinic where he became involved with providing services to people with HIV/AIDS in the early years of the epidemic.

A write-up on Jones-Hennin by D.C.’s Rainbow History Project, which named him a Community Pioneer, its highest honor, said Jones-Hennin managed several federal and state HIV/AIDS research and evaluation projects while working for a national management consulting firm.

Jones-Hennin is credited with breaking ground in the then gay and lesbian movement in 1978 when he co-founded the National Coalition of Black Gays, which became the first national advocacy group for gay and lesbian African Americans. One year later in 1979, he served as logistics coordinator for the first ever National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

During the March on Washington weekend Jones-Hennin helped to organize a National Third World LGBT Conference at Howard University, which led to the creation by students of the Howard University Lambda Student Alliance, the first known LGBT organization at a historically Black college or university in the U.S.

Among his other activities, Jones-Hennin worked as minority affairs director of the National AIDS Network, was a founding member of the Gay Married Men’s Association, and helped co-found the National Association of Black & White Men Together. During the administration of President Jimmy Carter, Jones-Hennin participated in the first delegation of gay people of color to meet with officials working for a U.S. president, according to the National Black Justice Coalition write-up on Jones-Hennin.

Christopher Hennin said he and Jones-Hennin were married in 2014 and began spending winters in Mexico around 1998, in part, because the cold weather had a negative effect on Jones-Hennin’s spinal stenosis condition, which at one point, required that he undergo surgery to treat the condition, which sometimes caused intense pain.

“He was a person totally dedicated to turning adversity into hope,” Christopher Hennin said of his husband. “His passion was definitely social change and improving people’s well-being,” said Hennin, describing Jones-Hennin as a “very impressive 21st century renaissance thinker.”

Hennin said a memorial service and celebration of Jones-Hennin’s life was being planned sometime later this year at D.C.’s Metropolitan Community Church, where Jones-Hennin’s ashes will be placed in a crypt.

Lesbian activist Susan Silber, one of Jones-Hennin’s longtime friends, said she viewed him as the LGBTQ community’s Bayard Rustin in his role as the “amazing organizer” of the first national Lesbian and Gay March on Washington and as lead organizer of the Third World LGBT Conference.

“ABilly lit up the room with his warmth and charisma,” Silber said.

Jones-Hennin is survived by his husband Christopher Hennin; his sister Pat Jones; his children Valerie Jones, Anthony ‘TJ’ Jones, Forrest ‘Peaches’ Taylor, Danielle Silber, and Avi Silber; 10 grandchildren; and 11 great grandchildren.

Family members have invited those who knew Jones-Hennin to share their memories of him online, which they plan to compile and share with his friends and family members:

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSeBiRDTlZFi4U8s7j26bEH5UChj5fgfpeklL5Km2q34eS3V3A/viewform

-

Africa2 days ago

Africa2 days agoCongolese lawmaker introduces anti-homosexuality bill

-

Colorado4 days ago

Colorado4 days agoFive transgender, nonbinary ICE detainees allege mistreatment at Colo. detention center

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoFirst lady warns Trump is ‘dangerous to the LGBTQ community’ at HRC event

-

Books5 days ago

Books5 days agoNew book offers observations on race, beauty, love