World

Shelters for LGBTQ asylum seekers on Mexico-US border ‘overwhelmed’

Nearly 50 people living at Jardín de las Mariposas in Tijuana

Editor’s note: International News Editor Michael K. Lavers was on assignment for the Washington Blade in Mexico, Honduras and El Salvador from July 11-25.

TIJUANA, Mexico — Marvin is a 23-year-old gay man from Dulce Nombre, a municipality in Honduras’ Copán department.

He left Honduras with a migrant caravan on Jan. 13, 2020, in order to escape the discrimination he said he would have suffered if his family and neighbors knew he is gay. Marvin spent eight months in the custody of Mexican immigration officials until they released him last November.

He was in the Mexican border city of Tijuana in April when a cousin told him his younger brother had been murdered. Marvin, who is currently living at Jardín de las Mariposas, a shelter for LGBTQ asylum seekers in Tijuana, began to sob when the Blade saw a picture of his brother’s body in the morgue in San Pedro Sula, Honduras’ second-largest city.

“He didn’t mess with anyone,” said Marvin.

Marvin is one of 47 people who were living at Jardín de las Mariposas when the Blade visited it on July 12. The shelter’s maximum capacity is 40.

A lesbian woman who asked the Blade not to publish her name said she fled El Salvador in January after MS-13 gang members threatened to kill her because she could not pay them the money they demanded from her. She said members of 18th Street, another gang, attacked her son after he refused to sell drugs.

“They hit him very hard; very, very hard,” the lesbian woman told the Blade at Jardín de las Mariposas, speaking through tears.

Olvin, a 22-year-old gay man from El Progreso, a city in Honduras’ Yoro department, left the country in January.

He said he and his partner of three years lived together in Tapachula, a city in Mexico’s Chiapas state that is close to the country’s border with Guatemala, for several months. Olvin said gang members threatened them and they suffered discrimination because of their sexual orientation.

Olvin told the Blade he rescued his partner from an apartment building one night after he refused to sell drugs, and they ran to a nearby park. Olvin, who was crying when he spoke with the Blade at Jardín de las Mariposas, said he left Tapachula a few days later without his partner.

Olvin arrived at the shelter a few hours before the Blade visited. He said he wants to ask for asylum in the U.S.

“I want to live in a safe place,” said Olvin.

Kelly West is a transgender woman who fled discrimination and persecution she said she suffered in Jamaica.

She flew to Panama City and then to Mexican city of Guadalajara before she arrived in Tijuana on June 16. West said she and a group of eight other LGBTQ asylum seekers tried to “run over the line at the border” between Mexico and the U.S., but Mexican police stopped them.

“We had to run for our lives,” West told the Blade at Jardín de las Mariposas. “I even ran without my shoes. I jumped over a bridge.”

She said she and three of the other asylum seekers with whom she tried to enter the U.S. went to another shelter for LGBTQ asylum seekers in Tijuana, but it was full. West said the shelter referred them to Jardín de las Mariposas.

“I really like it here,” she told the Blade. “Here I can be who I want, I can dress how I want to. I can wear my heels, I can wear my hair. I can just be feminine everyday.”

Jaime Marín, who runs Jardín de las Mariposas with his mother, Yolanda Rocha, noted some residents were sleeping in a tent in the backyard because the shelter is over capacity.

“We’re overpopulated with a lot of residents,” Marín told the Blade.

Title 42, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rule that closed the Southern border to most asylum seekers and migrants because of the coronavirus pandemic, remains in place.

Vice President Kamala Harris and other administration officials have publicly acknowledged that violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity is one of the “root causes” of migration from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. The White House has told migrants not to travel to the U.S.-Mexico border, but Marín said the number of people who have traveled to Tijuana since President Biden took office has increased dramatically.

The previous White House forced tens of thousands of asylum seekers to pursue their cases in Mexico under its Migrant Protection Protocols program. The Biden administration on June 1 officially ended MPP.

“The process has been easier, which means they’re no longer staying months or years,” Marín told the Blade. “They submit their application, let’s say today, and they get a response for a date in two weeks. They’re basically in the United States within a month.”

Marvin hopes to use the picture of his brother’s body in the morgue and Honduran newspaper articles about his murder as evidence to support his asylum case. Marvin, however, has yet to find someone to sponsor him.

“My goal … is to go to the United States,” he said.

Marín told the Blade the two other shelters for LGBTQ asylum seekers in Tijuana are also at maximum capacity. Marín said U.S. immigration officials are also “overwhelmed” with new asylum applications.

“It might take a little bit longer than a month because of the number of people that are basically coming and we just have to increase the work we do as well because we are getting a lot more work too,” he told the Blade. “We are overwhelmed as well.”

Fire destroyed lesbian-run Mexicali migrant shelter on July 9

Centro Comunitario de Bienestar Social (COBINA) in Mexicali, a border city that is roughly 2 1/2 hours east of Tijuana, is a group that serves LGBTQ people and other vulnerable groups.

It runs three migrant shelters in the city, which borders Calexico, Calif., in California’s Imperial Valley. An electrical fire that destroyed COBINA’s Refugio del Migrante on July 9 displaced the 152 migrants from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and other countries who were living there.

Some of the shelter’s residents were living in COBINA’s offices when the Blade visited them on July 12.

“We need resources to rebuild the shelter, to buy wood, to buy everything that is needed,” COBINA President Altagracia Tamayo told the Blade.

The Organization for Refuge, Asylum and Migration has raised $2,600 for COBINA to use to buy clothes, food and diapers for the displaced migrants and their children. The ORAM funds will also allow COBINA to buy portable air conditioning units. (The temperature in Mexicali was 108 degrees when the Blade reported from there.)

Tamayo told the Blade that COBINA has been working with the U.N. Refugee Agency and the International Organization for Migration to assist the displaced migrants.

Jardín de las Mariposas moved into a new house in May. It is less than four miles from El Chaparral, the main port of entry between Tijuana and San Diego.

Alight, formerly known as the American Refugee Agency, recently worked with ORAM to install security cameras and purchase new furniture for Jardín de las Mariposas. They also painted the shelter and a mural, installed solar heaters on the roof, planted plants and renovated the backyard.

This work is part of Alight’s “A Little Piece of Home” initiative that works to improve shelters for migrants and refugees along the border.

“This is beautiful because they are helping us and not letting us down,” Marín told the Blade. “They’re basically giving us hope to continue this fight that we have.”

Books

New book profiles LGBTQ Ukrainians, documents war experiences

Tuesday marks four years since Russia attacked Ukraine

Journalist J. Lester Feder’s new book profiles LGBTQ Ukrainians and their experiences during Russia’s war against their country.

Feder for “The Queer Face of War: Portraits and Stories from Ukraine” interviewed and photographed LGBTQ Ukrainians in Kyiv, the country’s capital, and in other cities. They include Olena Hloba, the co-founder of Tergo, a support group for parents and friends of LGBTQ Ukrainians, who fled her home in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha shortly after Russia launched its war on Feb. 24, 2022.

Russian soldiers killed civilians as they withdrew from Bucha. Videos and photographs that emerged from the Kyiv suburb showed dead bodies with their hands tied behind their back and other signs of torture.

Olena Shevchenko, chair of Insight, a Ukrainian LGBTQ rights group, wrote the book’s forward.

The book also profiles Viktor Pylypenko, a gay man who the Ukrainian military assigned to the 72nd Mechanized Black Cossack Brigade after the war began. Feder writes Pylypenko’s unit “was deployed to some of the fiercest and most important battles of the war.”

“The brigade was pivotal to beating Russian forces back from Kyiv in their initial attempt to take the capital, helping them liberate territory near Kharkiv and defending the front lines in Donbas,” wrote Feder.

Pylypenko spent two years fighting “on Ukraine’s most dangerous battlefields, serving primarily as a medic.”

“At times he felt he was living in a horror movie, watching tank shells tear his fellow soldiers apart before his eyes,” wrote Feder. “He held many men as they took their final breaths. Of the roughly one hundred who entered the unit with him, only six remained when he was discharged in 2024. He didn’t leave by choice: he went home to take care of his father, who had suffered a stroke.”

Feder notes one of Pylypenko’s former commanders attacked him online when he came out. Pylypenko said another commander defended him.

Feder also profiled Diana and Oleksii Polukhin, two residents of Kherson, a port city in southern Ukraine that is near the mouth of the Dnieper River.

Ukrainian forces regained control of Kherson in November 2022, nine months after Russia occupied it.

Diana, a cigarette vender, and Polukhin told Feder that Russian forces demanded they disclose the names of other LGBTQ Ukrainians in Kherson. Russian forces also tortured Diana and Polukhin while in their custody.

Polukhim is the first LGBTQ victim of Russian persecution to report their case to Ukrainian prosecutors.

Feder, who is of Ukrainian descent, first visited Ukraine in 2013 when he wrote for BuzzFeed.

He was Outright International’s Senior Fellow for Emergency Research from 2021-2023. Feder last traveled to Ukraine in December 2024.

Feder spoke about his book at Politics and Prose at the Wharf in Southwest D.C. on Feb. 6. The Washington Blade spoke with Feder on Feb. 20.

Feder told the Blade he began to work on the book when he was at Outright International and working with humanitarian groups on how to better serve LGBTQ Ukrainians. Feder said military service requirements, a lack of access to hormone therapy and documents that accurately reflect a person’s gender identity and LGBTQ-friendly shelters are among the myriad challenges that LGBTQ Ukrainians have faced since the war began.

“All of these were components of a queer experience of war that was not well documented, and we had never seen in one place, especially with photos,” he told the Blade. “I felt really called to do that, not only because of what was happening in Ukraine, but also as a way to bring to the surface issues that we’d had seen in Iraq and Syria and Afghanistan.”

Feder also spoke with the Blade about the war’s geopolitical implications.

Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2013 signed a law that bans the “promotion of homosexuality” to minors.

The 2014 Winter Olympics took place in Sochi, a Russian resort city on the Black Sea. Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine a few weeks after the games ended.

Russia’s anti-LGBTQ crackdown has continued over the last decade.

The Russian Supreme Court in 2023 ruled the “international LGBT movement” is an extremist organization and banned it. The Russian Justice Ministry last month designated ILGA World, a global LGBTQ and intersex rights group, as an “undesirable” organization.

Ukraine, meanwhile, has sought to align itself with Europe.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy after a 2021 meeting with then-President Joe Biden at the White House said his country would continue to fight discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. (Zelenskyy’s relationship with the U.S. has grown more tense since the Trump-Vance administration took office.) Zelenskyy in 2022 publicly backed civil partnerships for same-sex couples.

Then-Ukrainian Ambassador to the U.S. Oksana Markarova in 2023 applauded Kyiv Pride and other LGBTQ and intersex rights groups in her country when she spoke at a photo exhibit at Ukraine House in D.C. that highlighted LGBTQ and intersex soldiers. Then-Kyiv Pride Executive Director Lenny Emson, who Feder profiles in his book, was among those who attended the event.

“Thank you for everything you do in Kyiv, and thank you for everything that you do in order to fight the discrimination that still is somewhere in Ukraine,” said Markarova. “Not everything is perfect yet, but you know, I think we are moving in the right direction. And we together will not only fight the external enemy, but also will see equality.”

Feder in response to the Blade’s question about why he decided to write his book said he “didn’t feel” the “significance of Russia’s war against Ukraine” for LGBTQ people around the world “was fully understood.”

“This was an opportunity to tell that big story,” he said.

“The crackdown on LGBT rights inside Russia was essentially a laboratory for a strategy of attacking democratic values by attacking queer rights and it was one as Ukraine was getting closet to Europe back in 2013, 2014,” he added. “It was a strategy they were using as part of their foreign policy, and it was one they were using not only in Ukraine over the past decade, but around the world.”

Feder said Republicans are using “that same strategy to attack queer people, to attack democracy itself.”

“I felt like it was important that Americans understand that history,” he said.

Netherlands

Rob Jetten becomes first gay Dutch prime minister

38-year-old head of government sworn in on Monday

Rob Jetten on Monday became the Netherland’s first openly gay prime minister.

Jetten’s centrist D66 party won the country’s elections last October, narrowly defeating Geert Wilders’ far-right Party for Freedom.

King Willem-Alexander on Monday swore in Jetten, who is also the country’s youngest-ever prime minister. The Associated Press notes Jetten’s coalition government includes the center-right Christian Democrats and the center-right People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy.

“Proud to be able to do this together,” said Jetten in an X post before Willem-Alexander swore him in.

COC Nederland, a Dutch LGBTQ advocacy group, in a statement said Jetten “becoming prime minister shows that your sexual orientation doesn’t have to matter.”

“You can become a construction worker, a doctor, a lawyer, and even prime minister,” said COC Nederland.

The advocacy group noted Jetten has said his government will implement its “Rainbow Agreement” that include calls for strengthening nondiscrimination laws “to better protect transgender and intersex people,” appointing more “discrimination investigators … to address violence against LGBTQ+ people and other minorities,” and introducing measures “to promote acceptance in schools.”

“COC will hold the Cabinet to that promise,” said COC Nederland.

Jetten’s fiancé is Nicolás Keenen, an Argentine field hockey player who competed in the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris.

Jetten is one of two openly gay heads of government: Andorran Prime Minister Xavier Espot Zamora came out in 2023. Gay Latvian President Edgars Rinkēvičs, who is the country’s head of state, took office in 2023.

Leo Varadkar, who was Ireland’s prime minister from 2017-2020 and from 2022-2024, and Xavier Bettel, who was Luxembourg’s prime minister from 2013-2023, are gay. Ana Brnabić, who was Serbia’s prime minister from 2017-2024, is a lesbian.

Former Icelandic Prime Minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir in 2009 became the world’s first openly lesbian head of government. Former Belgian Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo, former San Marino Captain Regent Paolo Rondelli, and former French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal are also openly gay.

Colombian presidential candidate Claudia López, who is the former mayor of Bogotá, the Colombian capital, would become her country’s first female and first lesbian president if she wins the country’s presidential election that is taking place later this year.

Ecuador

Justicia reconoce delito de odio en caso de bullying en Instituto Nacional Mejía de Ecuador

Johana B se suicidó el 11 de abril de 2023

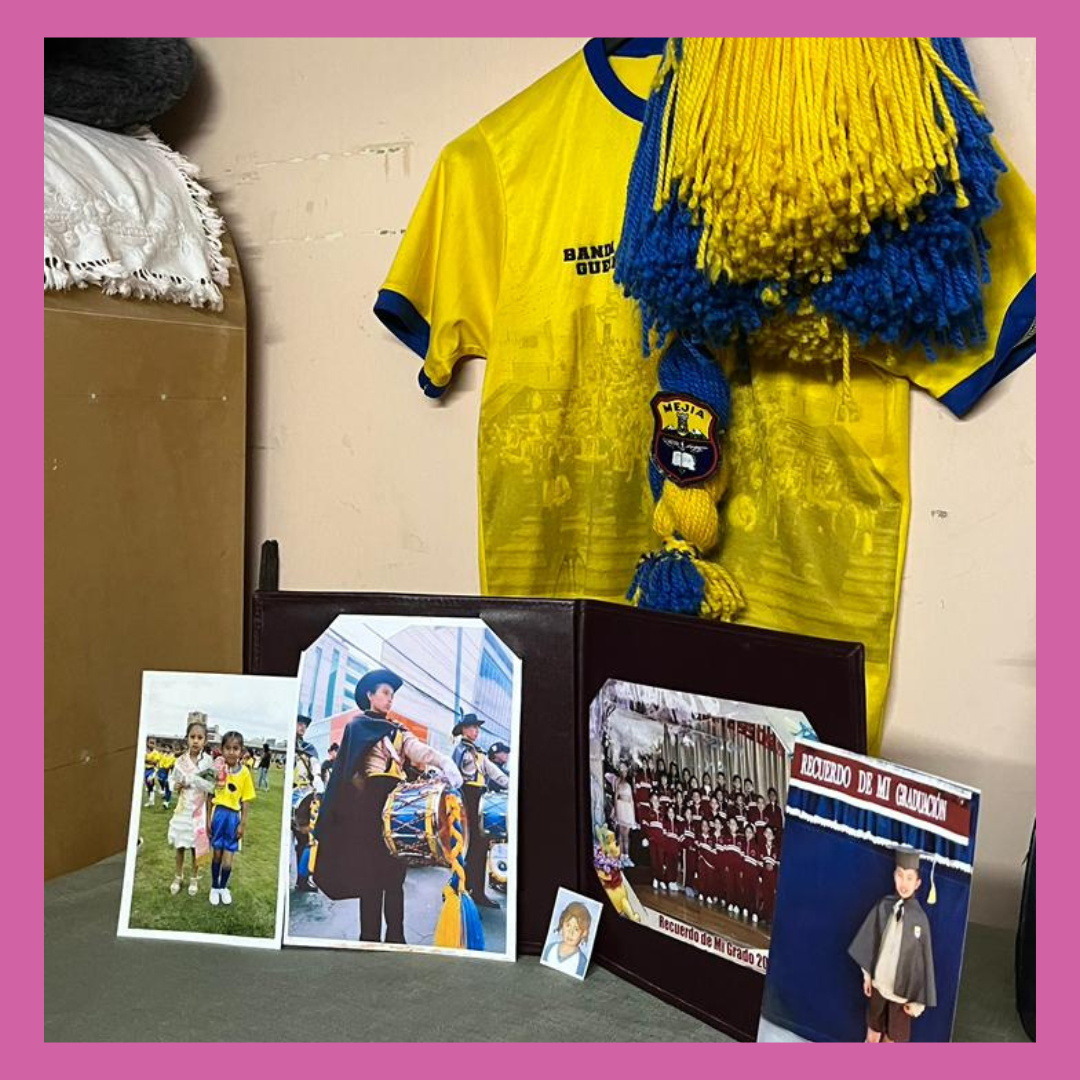

A casi tres años del suicidio de Johana B., quien estudió en el Instituto Nacional Mejía, colegio emblemático de Quito, el Tribunal de la Corte Nacional de Justicia ratificó la condena para el alumno responsable del acoso escolar que la llevó a quitarse la vida.

Según información de la Fiscalía, el fallo de última instancia deja en firme la condena de cuatro años de internamiento en un centro para adolescentes infractores, en una audiencia de casación pedida por la defensa del agresor, tres meses antes de que prescriba el caso.

Con la sentencia, este caso es uno de los primeros en el país en reconocer actos de odio por violencia de género, delito tipificado en el artículo 177 del Código Orgánico Penal Integral (COIP).

El suicidio de Johana B. ocurrió el 11 abril de 2023 y fue consecuencia del acoso escolar por estereotipos de género que enfrentó la estudiante por parte de su agresor, quien constantemente la insultaba y agredía por su forma de vestir, llevar el cabello corto o practicar actividades que hace años se consideraban exclusivamente para hombres, como ser mando de la Banda de Paz en el Instituto Nacional Mejía.

Desde la muerte de Johana, su familia buscaba justicia. Su padre, José, en una entrevista concedida a edición cientonce para la investigación periodística Los suicidios que quedan en el clóset a causa de la omisión estatal afirmó que su hija era acosada por su compañero y otres estudiantes con apodos como “marimacha”, lo que también fue corroborado en los testimonios recogidos por la Unidad de Justicia Juvenil No. 4 de la Fiscalía.

Los resultados de la autopsia psicológica y del examen antropológico realizados tras la muerte de Johana confirmaron las versiones de sus compañeras y docentes: que su agresor la acosó de manera sistemática durante dos años. Los empujones, jalones de cabello o burlas, incluso por su situación económica, eran constantes en el aula de clase.

La violencia que recibió Johana escaló cuando su compañero le dio un codazo en la espalda ocasionándole una lesión que le imposibilitó caminar y asistir a clases.

Días después del hecho, la adolescente se quitó la vida en su casa, tras escuchar que la madre del agresor se negó a pagar la mitad del valor de una tomografía para determinar la lesión en su espalda, tal como lo había acordado previamente con sus padres y frente al personal del DECE (Departamento de Consejería Estudiantil del colegio), según versiones de su familia y la Fiscalía.

#AFONDO | Johana se suicidó el 11 de abril de 2023, tras ser víctima de acoso escolar por no cumplir con estereotipos femeninos 😢.

Dos semanas antes, uno de sus compañeros le dio un codazo en la espalda, ocasionándole una lesión que le imposibilitó caminar 🧵 pic.twitter.com/bXKUs9YYOm

— EdicionCientonce (@EdCientonce) September 3, 2025

“Era una chica linda, fuerte, alegre. Siempre nos llevamos muy bien, hemos compartido todo. Nos dejó muchos recuerdos y todos nos sentimos tristes; siempre estamos pensando en ella. Es un vacío tan grande aquí, en este lugar”, expresó José a Edición Cientonce el año pasado.

Para la fiscal del caso y de la Unidad de Justicia Juvenil de la Fiscalía, Martha Reino, el suicidio de la adolescente fue un agravante que se contempló durante la audiencia de juzgamiento de marzo de 2024, según explicó a este medio el año pasado. Desde entonces, la familia del agresor presentó un recurso de casación en la Corte Nacional de Justicia, que provocó la dilatación del proceso.

En el fallo de última instancia, el Tribunal también dispuso que el agresor pague $3.000 a la familia de Johana B. como reparación integral. Además, el adolescente deberá recibir medidas socioeducativas, de acuerdo al artículo 385 del Código Orgánico de la Niñez y Adolescencia, señala la Fiscalía.

El caso de Johana también destapó las omisiones y negligencias del personal del DECE y docentes del Instituto Nacional Mejía. En la etapa de instrucción fiscal se comprobó que no se aplicaron los protocolos respectivos para proteger a la víctima.

De hecho, la Fiscalía conoció el caso a raíz de la denuncia que presentó su padre, José, y no por el DECE, aseguró la fiscal el año pasado a Edición Cientonce.

Pese a estas omisiones presentadas en el proceso, el fallo de última instancia sólo ratificó la condena para el estudiante.

-

Mexico5 days ago

Mexico5 days agoUS Embassy in Mexico issues shelter in place order for Puerto Vallarta

-

Real Estate5 days ago

Real Estate5 days ago2026: prices, pace, and winter weather

-

Theater5 days ago

Theater5 days agoJosé Zayas brings ‘The House of Bernarda Alba’ to GALA Hispanic Theatre

-

Netherlands4 days ago

Netherlands4 days agoRob Jetten becomes first gay Dutch prime minister