South America

Brazil LGBTQ activists, HIV/AIDS service providers fear Bolsonaro reelection

Presidential election to take place in October

(Editor’s note: Two sources quoted in this story — Fernanda Fonseca and Beto de Jesus — shared their personal views on the subject. Their remarks do not represent the views of AIDS Healthcare Foundation.)

SALVADOR, Brazil — Fernanda Fonseca was the coordinator of the Brazilian Health Ministry’s program to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, syphilis and viral hepatitis B in 2019 when she attended the International AIDS Society’s Conference on HIV Science in Mexico City.

Fonseca, who attended the conference in her personal capacity, made a presentation that focused on the issue. Her husband, who at the time coordinated the Brazilian Health Ministry’s viral hepatitis program, also traveled to Mexico City.

One of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s sons soon posted to Twitter a picture of a doctored presentation “about trans community rights, and LGBT community rights” that an unnamed “couple” had made at the conference. The “couple” who Bolsonaro’s son targeted was Fonseca and her husband.

“He was like, this is what the government is standing for,” Fonseca told the Washington Blade on March 16 during an interview at a coffee shop in Salvador, a city in northeastern Brazil that is the capital of Bahia state.

Bolsonaro took office as Brazil’s president on Jan. 1, 2019, after he defeated then-São Paulo Mayor Fernando Haddad in the second round of the country’s presidential election that took place the previous October.

Fonseca noted one of the first things Bolsonaro did as president was to remove HIV from the name of the Health Ministry department that specifically fights HIV/AIDS in Brazil.

It was previously the Department of Vigilance, Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections, HIV/AIDS and Viral Hepatitis. It is now called the Department of Chronic Conditions and Sexually Transmitted Infections.

Bolsonaro fired the department’s director, Adele Benzaken, after he took office. Fonseca said her position was also eliminated without her knowledge while she was on maternity leave.

Fonseca eventually resigned. She now works for AIDS Healthcare Foundation Brazil as its country medical program director.

“They destroyed my department,” she said. “When I came back (from maternity leave), no one was answering my calls.”

Fonseca is one of the many HIV/AIDS service providers and LGBTQ activists with whom the Blade spoke in Brazil — Salvador, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro — from March 12-21. They all sharply criticized Bolsonaro and expressed concern over what may happen in Brazil if he wins re-election later this year.

Bolsonaro is a former Brazilian Army captain who represented Rio de Janeiro in the country’s Congress from 1991-2018.

Fonseca told the Blade that Bolsonaro has banned the Health Ministry from buying lubricants, while adding he “wanted to shut down everything related to HIV.”

“It’s very specific. It’s very homophobic,” she said. “I don’t know who informs him.”

AIDS Healthcare Foundation Brazil Program Manager Beto de Jesus during a March 14 interview at his office near São Paulo’s Praça da Republica noted Bolsonaro has suggested COVID-19 vaccines can cause AIDS.

“To him, the question of AIDS is connected to faggots,” said De Jesus.

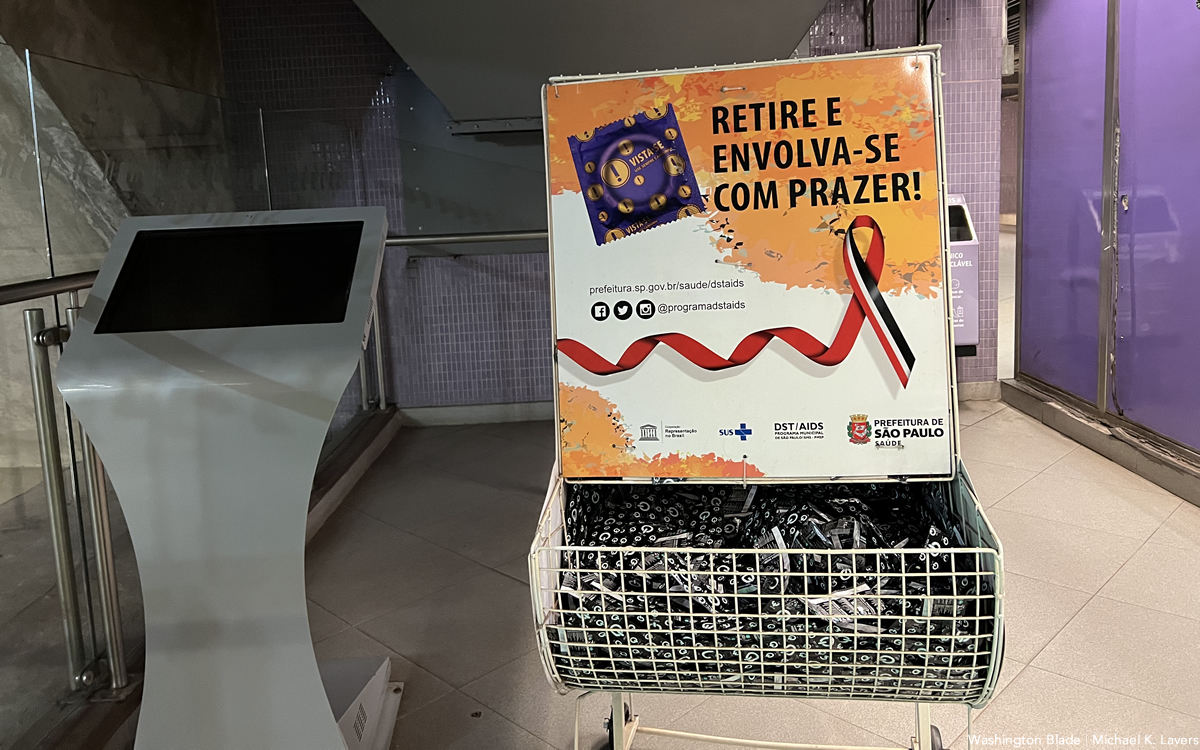

São Paulo’s Municipal Health Secretary distributes free condoms on the city’s subway system. The Brazilian Health Ministry has donated to AIDS Healthcare Foundation antitretroviral drugs that it provides to Venezuelan migrants who receive care at their clinics in Colombia.

Bolsonaro, among many things, has encouraged fathers to beat their sons if they think they are gay. (His son, Rio Municipal Councilman Carlos Bolsonaro, is reportedly gay.)

Jair Bolsonaro in March 2019 during a press conference with then-President Trump in the White House Rose Garden stressed his “respect of traditional family values” — he’s twice divorced and married his third wife, Michelle Bolsonaro, in 2017 — and opposition to “gender ideology.”

A report that Human Rights Watch released earlier this month notes Bolsonaro “has a long history of mischaracterizing and vocally opposing gender and sexuality education, including on the grounds that it constitutes ‘early sexualization’.” Bolsonaro has supported legislation that would limit LGBTQ-specific curricula in the country’s schools, even after the Brazilian Supreme Court struck down local and state laws on the issue.

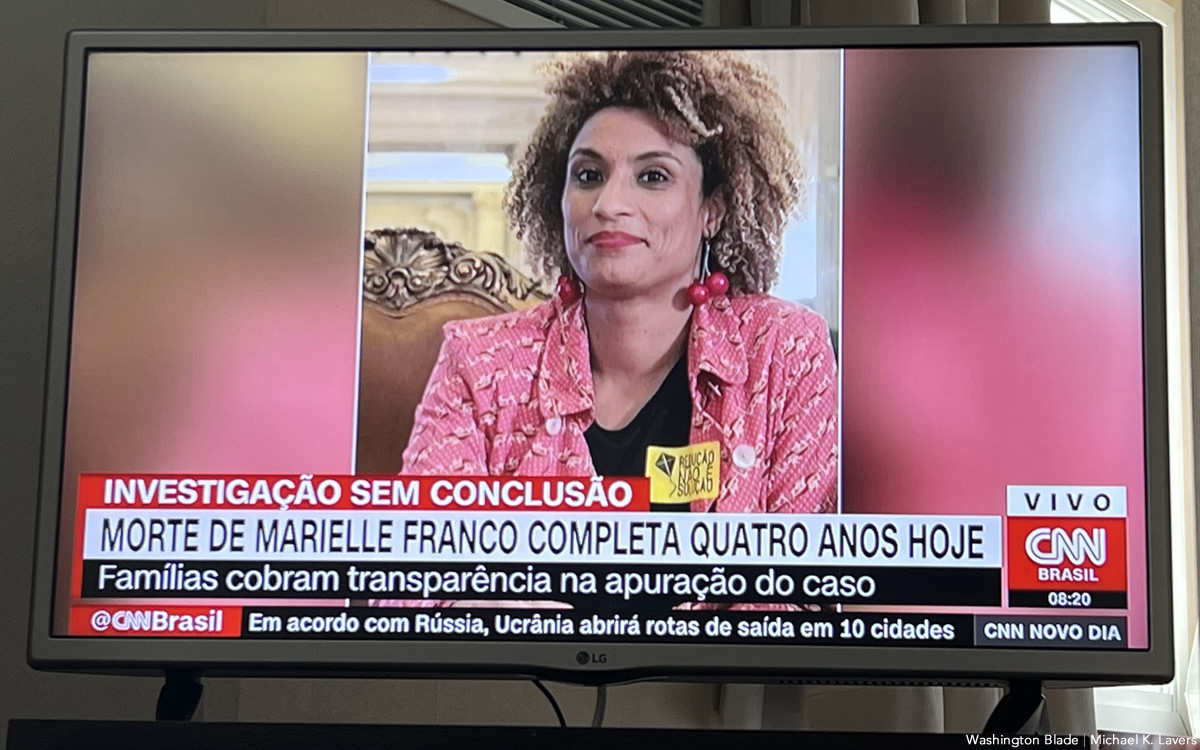

Jair Bolsonaro was not president when Rio Municipal Councilwoman Marielle Franco, a bisexual woman of African descent, and her driver, Anderson Gomes, were murdered in Rio’s Lapa neighborhood on March 14, 2018.

Ronnie Lessa, one of the two former police officers who has been arrested in connection with the murders, lived in the same large condominium in Rio’s exclusive Barra da Tijuca neighborhood in which Jair Bolsonaro lives. Franco’s widow, Rio Municipal Councilwoman Mônica Benício, on March 19 said this fact is “just a coincidence.”

Benício during the interview that took place at a coffee shop in downtown Rio stressed Jair Bolsonaro’s rhetoric against LGBTQ Brazilians, women and other groups was “known” before he became president. Benício also acknowledged it resonates with a segment of Brazilian society.

“It is an absolutely despicable posture and incompatible with a posture of the president of the republic,” said Benício.

Two Brazilian LGBTQ rights groups — Aliança Nacional LGBTI and Grupo Gay da Bahia — in a report they released on May 10 notes 300 LGBTQ Brazilians “suffered violent deaths” because they were murdered or died by suicide. The organizations specifically note Salvador is the most dangerous state capital for LGBTQ people.

The report notes 28 percent of the murder victims were killed with knives, machetes, scissors, hoes and other weapons. One of them was stabbed 95 times.

“The cruelty of how many of these executions were committed demonstrates the extreme hatred of the criminals, who are not content with killing, disfigure the victim washing their murderous homophobia in the spilled blood,” said Aliança Nacional LGBTI President Toni Reis in the report’s introduction.

Grupo Gay da Bahia President Marcelo Cerqueira on March 15 told the Blade during an interview in Salvador that race, poverty, class, machismo and family structures all contribute to the area’s high rate of violence against LGBTQ people.

“There are many relationships with asymmetrical power dynamics,” he noted.

Keila Simpson is the president of Associaçao Nacional de Travestis e Transexuais (National Association of Travestis and Transsexuals), a Brazilian transgender rights group known by the acronym ANTRA.

She noted to the Blade on March 16 during an interview at her office in Salvador’s Pelourinho neighborhood that the Supreme Court in 2018 ruled trans Brazilians can legally change their name and gender without medical intervention or a judicial order. Simpson said trans Brazilians nevertheless continue to suffer from discrimination, a lack of formal employment and educational opportunities and police violence because of their gender identity. She also added efforts to combat violence against LGBTQ Brazilians have become even more difficult because Bolsonaro is “propagating violence against LGBTQ people every day.”

“It increases the possibility of people who are already violent by nature to continue committing violence,” said Simpson.

Mariah Rafaela Silva, a trans woman of indigenous descent who works with the Washington-based International Institute on Race, Equality and Human Rights, agreed when she and her colleague, Isaac Porto, spoke with the Blade at a restaurant in Rio’s Ipanema neighborhood on March 21.

“If I would choose a word to define Bolsonaro it would be danger,” said Silva. “He represents a danger to the environment. He represents a danger to diversity. He represents a danger to Black people. He represents a danger to indigenous people.”

Rio de Janeiro (State) Legislative Assemblywoman Renata Souza is a Black feminist who grew up with Franco in Maré, a favela that is close to Rio’s Galeão International Airport, and worked with her for 12 years.

Souza in March traveled to D.C. and met with Serra Sippel, chief global advocacy officer for Fòs Feminista, a global women’s rights group, White House Gender Policy Council Senior Advisor Rachel Vogelstein and other officials and women’s rights activists. Souza on Tuesday noted to the Blade that she also denounced Franco’s murder, the “escalation of police violence and Black genocide in Brazil’s peripheries and favelas” and called for international observers in the country for the presidential election when she spoke at the Organization of American States and to members of Congress.

“President Bolsonaro is the expression of a capitalist political project that serves private national and international interests related to the military-industrial complex, religious fundamentalism, agribusiness and the predatory exploitation of natural resources,” said Souza. “This project’s social base comes from the formation of an ideal of barbarism through the use of violence as language and hate as a fuel that spreads a misogynist, racist and fundamentalist culture, discriminatory customs and policies that predatory to nature and to being human.”

The first round of Brazil’s presidential election will take place on Oct. 2.

Polls indicate Bolsonaro is trailing former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Bolsonaro has already sought to discredit the country’s electoral system, even though a group of more than 20 would-be hackers who gathered in the Brazilian capital of Brasília last week failed to infiltrate it.

Da Silva, who was Brazil’s president from 2003-2010, is a member of the country’s Workers’ Party.

Sergio Moro, a judge who Jair Bolsonaro later tapped as his government’s Justice and Public Security Minister, in 2017 sentenced Da Silva to 9 1/2 years in prison after his conviction on money laundering and corruption charges that stemmed from Operation Car Wash. The Supreme Court in November 2019 ordered Da Silva’s release.

Marina Reidel, a trans woman who is the director of the country’s Women, Family and Human Rights Department, on Monday told the Blade to email a request for comment on Jair Bolsonaro’s anti-LGBTQ record to a spokesperson. The Blade has yet to receive a response.

Julian Rodrigues, who was the coordinator of the Workers’ Party’s National Working Group from 2006-2012, on Tuesday from São Paulo noted Da Silva in 2004 created the Health Ministry’s “Brazil without Homophobia” campaign that he described as a “pioneering program for LGBT rights.” Rodrigues also highlighted Da Silva created the Culture Ministry’s Diversity Secretariat that, among other things, funded community centers and sought to make police officers and other law enforcement officials more LGBTQ-friendly.

Simpson noted the Health Ministry when Da Silva and President Dilma Rousseff were in office funded projects that specifically helped sex workers and other vulnerable groups.

Rousseff was in office in 2013 when the Supreme Court extended marriage rights to same-sex couples across the country. Michel Temer was Brazil’s president in 2018 when the Supreme Court issued its trans rights decision.

The Supreme Court on May 24, 2019, issued a ruling that criminalized homophobia and transphobia. Bolsonaro, who took office less than five months earlier, condemned the decision.

The Supreme Court in May 2020 struck down the country’s ban on men who have sex with men from donating blood. Brazil in 1999 became the first country in the world to ban so-called conversion therapy.

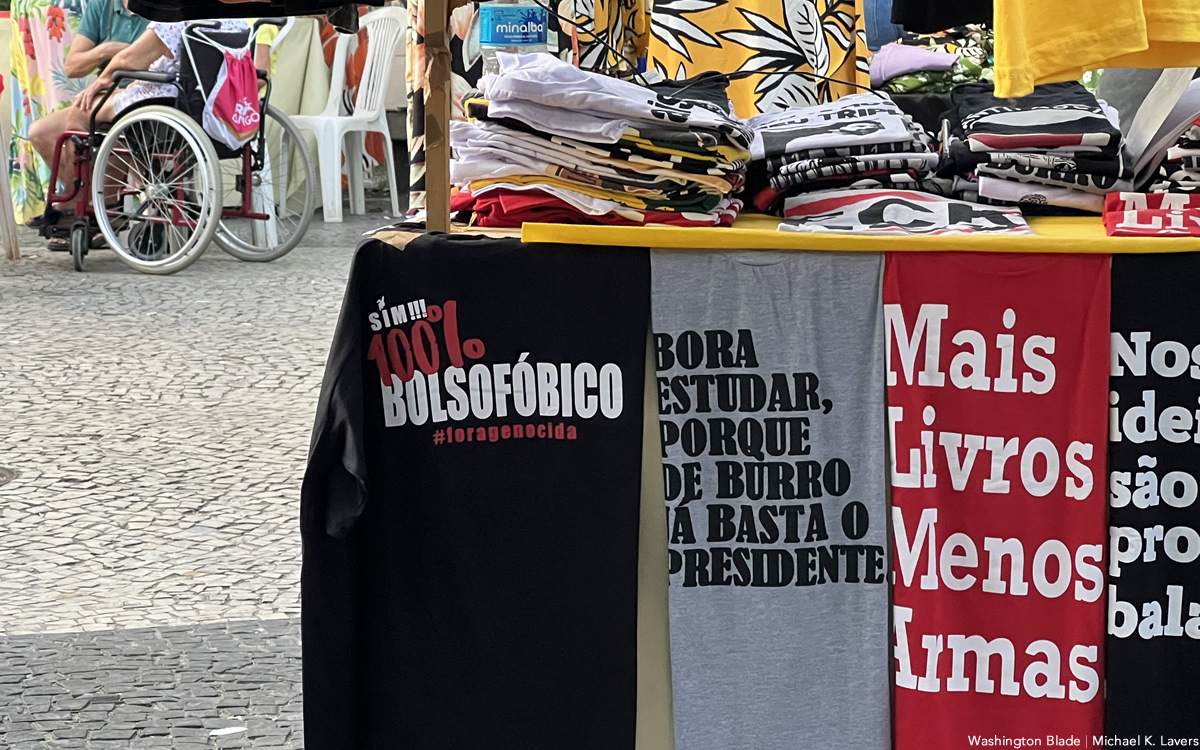

Rodrigues described Bolsonaro and his administration as “an extreme right-wing, authoritarian and fascist government that uses racial prejudice, gender prejudice and prejudice against LGBTs as engines to mobilize its conservative and reactionary social base.”

“It is a very dangerous government for Brazil’s democratic freedoms,” Rodrigues told the Blade. “The entire Brazilian LGBT movement is fighting ardently to defeat the Bolsonaro government and elect Lula, a progressive president who is committed to the rights of LGBTQ people and all Brazilian people.”

A gay man who was on Rio’s Ipanema Beach with his husband on March 20 told the Blade they support Jair Bolsonaro because they feel he has fought corruption in Brazil. They did, however, add that Jair Bolsonaro “should keep his mouth shut.”

Fonseca said her father voted for Bolsonaro in 2018 because he “hated” Da Silva.

“We don’t live in a democratic state anymore,” said Fonseca, who noted the Supreme Court eventually absolved Da Silva. “We can’t trust the police force. We can’t trust the legal system.”

“People who think like him now they believe they can say that, they have the right to say homophobic things, racist things. They can because our president says them, so it’s ok,” added Fonseca. “We need to remember that it’s not ok. I don’t think they are the majority, So I think when we have a leader again that is strong, we are going back on track.”

Cerqueira echoed Fonseca.

“(Bolsonaro) managed to energize prejudiced people who were not vocal before,” Cerqueira told the Blade on March 15 during an interview in Salvador. “People were afraid to say that I was racist, that I was homophobic, that I was prejudiced. Nowadays everybody wants to be homophobic.”

Porto noted conservatives continue to dominate the country’s Congress and Brazilians who are Black and/or LGBTQ lack political power. He told the Blade the situation in a post-Bolsonaro Brazil is “going to be complicated”

“Brazilian society has not changed,” said Porto. “There is a movement of people who are organized and recognize themselves as equal.”

“There’s a lot of damage that we have to repair,” added Silva.

Colombia

Colombia avanza hacia la igualdad para personas trans

Fue aprobado en Comisión Primera de la Cámara la Ley Integral Trans

En un hecho histórico para los derechos humanos en Colombia, la Comisión Primera de la Cámara de Representantes aprobó en primer debate el Proyecto de Ley 122 de 2024, conocido como la Ley Integral Trans, que busca garantizar la igualdad efectiva de las personas con identidades de género diversas en el país. Esta iniciativa, impulsada por más de cien organizaciones sociales defensoras de los derechos LGBTQ, congresistas de la comisión por la Diversidad y personas trans, representa un paso decisivo hacia el reconocimiento pleno de derechos para esta población históricamente marginada.

La Ley Integral Trans propone un marco normativo robusto para enfrentar la discriminación y promover la inclusión. Entre sus principales ejes se destacan el acceso a servicios de salud con enfoque diferencial, el reconocimiento de la identidad de género en todos los ámbitos de la vida, la creación de programas de empleo y educación para personas trans, así como medidas para garantizar el acceso a la justicia y la protección frente a violencias basadas en prejuicios.

Detractores hablan de ‘imposición ideológica

Sin embargo, el avance del proyecto no ha estado exento de polémicas. Algunos sectores conservadores han señalado que la iniciativa representa una “imposición ideológica”. La senadora y precandidata presidencial María Fernanda Cabal anunció públicamente que se opondrá al proyecto de Ley Integral Trans cuando llegue al Senado, argumentando que “todas las personas deben ser tratadas por igual” y que esta propuesta vulneraría un principio constitucional. Estas declaraciones anticipan un debate intenso en las próximas etapas legislativas.

El proyecto también establecelineamientos claros para que las instituciones públicas respeten el nombre y el género con los que las personas trans se identifican, en concordancia con su identidad de género, y contempla procesos de formación y sensibilización en entidades estatales. Además, impulsa políticas públicas en contextos clave como el trabajo, la educación, la cultura y el deporte, promoviendo una vida libre de discriminación y con garantías plenas de participación.

¿Qué sigue para que sea ley?

La Ley aún debe superar varios debates legislativos, incluyendo la plenaria en la Cámara y luego el paso al Senado; pero la sola aprobación en Comisión Primera ya constituye un hito en la lucha por la igualdad y la dignidad de las personas trans en Colombia. En un país donde esta población enfrenta altos niveles de exclusión, violencia y barreras estructurales, este avance legislativo renueva la esperanza de una transformación real.

Desde www.orgullolgbt.co, celebramos este logro, invitamos a unirnos en esta causa impulsándola en los círculos a los que tengamos acceso y reiteramos nuestro compromiso con la visibilidad, los derechos y la vida digna de las personas trans. La #LeyIntegralTrans bautizada “Ley Sara Millerey” en honor de la mujer trans recientemente asesinada en Bello, Antioquia (ver más aquí); no es solo una propuesta normativa: es un acto de justicia que busca asegurar condiciones reales para que todas las personas puedan vivir con libertad, seguridad y respeto por su identidad.

Colombia

Claudia López running for president of Colombia

Former Bogotá mayor married to Sen. Angélica Lozano

Former Bogotá Mayor Claudia López has announced she is running for president of Colombia.

“We begin today and we will win in a year,” she said in a social media post on June 3.

View this post on Instagram

López, 55, was a student protest movement leader, journalist, and political scientist before she entered politics. López returned to Colombia in 2013 after she earned her PhD in political science at Columbia University.

López in a speech she gave last December after the LGBTQ+ Victory Institute honored her at its annual International LGBTQ Leaders Conference in D.C. noted Juan Francisco “Kiko” Gomez, a former governor of La Guajíra, a department in northern Colombia, threatened to assassinate her because she wrote about his ties to criminal gangs.

A Bogotá judge in 2017 convicted Gómez of ordering members of a paramilitary group to kill former Barrancas Mayor Yandra Brito, her husband, and bodyguard and sentenced him to 55 years in prison.

López in 2014 returned to Colombia, and ran for the country’s Senate as a member of the center-left Green Alliance party after she recovered from breast cancer. López won after a 10-week campaign that cost $80,000.

López in 2018 was her party’s candidate to succeed then-President Juan Manuel Santos when he left office. López in 2019 became the first woman and first lesbian elected mayor of Bogotá, the Colombian capital and the country’s largest city.

López took office on Jan. 1, 2020, less than a month after she married her wife, Colombian Sen. Angélica Lozano. (López was not out when she was elected to the Senate.) López’s mayorship ended on Dec. 31, 2023. She was a 2024 Harvard University Advance Leadership Initiative fellow.

The first-round of Colombia’s presidential election will take place on May 31, 2026.

The country’s 1991 constitution prevents current President Gustavo Petro from seeking re-election.

López declared her candidacy four days before a gunman shot Sen. Miguel Uribe, a member of the opposition Democratic Center party who is seen as a probable presidential candidate, in the head during a rally in Bogotá’s Fontibón neighborhood.

She quickly condemned the shooting. López during an interview with the Washington Blade after the Victory Institute honored her called for an end to polarization in Colombia.

“We need to listen to each other again, we need to have a coffee with each other again, we need to touch each other’s skin,” she said.

López would be Colombia’s first female president if she wins. López would also become the third openly lesbian woman elected head of government — Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir was Iceland’s prime minister from 2009-2013 and Ana Brnabić was Serbia’s prime minister from 2017-2024.

Chile

Gay pharmacist’s murder sparks outrage in Chile

Francisco Albornoz’s body found in remote ravine on June 4

The latest revelations about the tragic death of Francisco Albornoz, a 21-year-old gay pharmacist whose body was found on June 4 in a remote ravine in the O’Higgins region 12 days after he disappeared, has left Chile’s LGBTQ community shocked.

The crime, which was initially surrounded by uncertainty and contradictory theories, has taken a darker and more shocking turn after prosecutors charged Christian González, an Ecuadorian doctor, and José Miguel Baeza, a Chilean chef, in connection with Albornoz’s murder. González and Baeza are in custody while authorities continue to investigate the case.

The Chilean Public Prosecutor’s Office has pointed to a premeditated “criminal plan” to murder Albornoz.

Rossana Folli, the prosecutor who is in charge of the case, says Albornoz died as a a result of traumatic encephalopathy after receiving multiple blows to the head inside an apartment in Ñuñoa, which is just outside of Santiago, the Chilean capital, early on May 24. The Prosecutor’s Office has categorically ruled out that Albornoz died of a drug overdose, as initial reports suggested.

“The fact that motivates and leads to the unfortunate death of Francisco is part of a criminal plan of the two defendants, aimed at ensuring his death and guaranteeing total impunity,” Folli told the court. “The seriousness of the facts led the judge to decree preventive detention for both defendants on the grounds that their freedom represents a danger to public safety.”

Prosecutors during a June 7 hearing that lasted almost eight hours presented conservations from the suspects’ cell phones that they say showed they planned the murder in advance.

“Here we already have one (for Albornoz.) If you bring chloroform, drugs, marijuana, etc.,” read one of the messages.

Security cameras captured the three men entering the apartment where the murder took place together.

Hours later, one of the suspects left with a suitcase and a shopping cart to transport Albornoz’s body, which had been wrapped in a sleeping bag. The route they followed to dispose of the body included a stop to buy drinks, potato chips, gloves, and a rope with which they finally descended a ravine to hide it.

Advocacy groups demand authorities investigate murder as hate crime

Although the Public Prosecutor’s Office has not yet officially classified the murder as a hate crime, LGBTQ organizations are already demanding authorities investigate this angle. Human rights groups have raised concerns over patterns of violence that affect queer people in Chile.

The Zamudio Law and other anti-discrimination laws exist. Activists, however, maintain crimes motivated by a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity are not properly prosecuted.

“This is not just a homicide, it is the cruelest expression of a society that still allows the dehumanization of LGBTQ+ people,” said a statement from Fundación Iguales, one of Chile’s main LGBTQ organizations. “We demand truth, justice, and guarantees of non-repetition.”

The Movement for Homosexual Integration and Liberation (Movilh), meanwhile, indicated that “since the first day the family contacted us, we have been in conversations with the Prosecutor’s Office so that this fatal outcome is thoroughly investigated, including the possible existence of homophobic motivations or components.”

The investigation into Albornoz’s murder continues, and the court has imposed a 90-day deadline for authorities to complete it.