Arts & Entertainment

Dynamic differences

Two brand new organs — two of the world’s best organists — four days in Washington

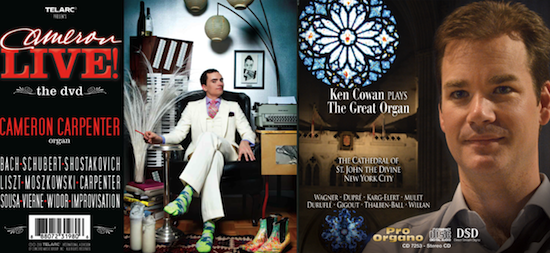

Ken Cowan, left, and Cameron Carpenter. (Cowan photo by Jim Cunningham, courtesy First Baptist Church; Carpenter photo by Heiko Laschitzki, courtesy Bucklesweet Media)

Pipe organ aficionados in Washington had the opportunity to gorge on an embarrassment of riches over the past few days. On Wednesday, iconoclast Cameron Carpenter played the Kennedy Center. Just four days later, traditionalist Ken Cowan performed at D.C.’s First Baptist Church.

The rare experience of having these two brilliant young organists here so close together was doubled by the fact that both venues in which they played just unveiled massive new organs.

The Rubenstein Family Organ at the Kennedy Center, a $2 million, 85-rank, four manual beauty by Casavant Freres, has 4,972 pipes and replaces the Filene Organ, an Aeolian Skinner from 1972 that was adequate at best. It’s a gift from Kennedy Center chairman David Rubenstein and his wife, Alice.

The new Austin organ at First Baptist is a 118-rank double (chancel and gallery) organ that has about 6,000 pipes and cost roughly $1.8 million. It’s only the second five-manual (i.e. five levels of keyboards) organ in Washington (National City Christian Church — which added to the wealth by hosting the equally good organist Adam Brakel just the week before — has the other) and replaces the church’s woefully underwhelming previous instrument, a relic Moller from 1948 that had just two manuals and about 2,100 pipes.

The new Austin Organ (Op. 2795) at First Baptist Church of Washington. (Blade photo by Joey DiGuglielmo)

The Rubenstein is a full pipe organ; First Baptist’s is majority pipe but is augmented with some digital stops. They’re not the largest organs in Washington — National Cathedral’s 1938 Skinner has 189 ranks and more than 10,647 pipes and the National Shrine’s two Moller organs have a combined 197 ranks and 10,748 pipes; National City’s has 105 ranks and nearly 7,600 pipes. Yet these are still major new additions to the District’s musical landscape. More pipes don’t necessarily mean more sound — just a larger range of tonal variation that’s available.

While both instruments have been previously heard, Carpenter’s program was the first “concert length” recital on the new organ at the Kennedy Center and opens a series that continues with Paul Jacobs — one of a very short list of young organists in the same league as Carpenter and Cowan — on Feb. 5 and Latvian organist Iveta Apkalna on May 21. Despite the Rubenstein organ only having been played publicly a handful of times thus far, it was Carpenter’s second time playing it. He played the fourth movement of Saint-Saens’s “Symphony No. 3 in C minor” (the “organ symphony”) on it with the National Symphony Orchestra on Sept. 29.

And while First Baptist organist/choirmaster Lawrence Schreiber gave the inaugural recital of the Austin organ on Sept. 15, Cowan’s performance this week was the first in the church’s “Distinguished Organist” series, which continues with a performance by Christopher Houlihan on Nov. 24. An hour-long recital featuring several guest players of the region will be held on Halloween at 7 p.m.

The two concerts — equally dazzling — were a study in contrasts, chiefly because of the vast difference of artistic and aesthetic choices from Carpenter, 32, and Cowan, 38. Both played fully from memory save for one short self-composed piece for which Carpenter used a score. Possessed, it appears, of equal talent, Carpenter is a colorful rabble rouser who clearly delights in shaking up the often staid world of organ music. One could never call Cowan staid — he simply lights his musical fires with a different brand of kerosene. His playing is every bit as technically impressive and boundary-pushing as Carpenter’s; he just does it while wearing a tux and in a setting — First Baptist — as traditional (albeit breathtaking) as it gets.

One may be momentarily intrigued by their differences — Cowan’s tux and everyman’s haircut to Carpenter’s Versace, tight leather pants and mohawk, the former’s straight sexual orientation (he’s married to violinist Lisa Shihoten) to the latter’s bisexuality, etc. — and insist only the sounds produced are of consequence, but it’s not that simple, for they’re each having a radically different impact on the world.

Since they’re of roughly equal ability, one quickly realizes there are other factors at play, some musical, some not, just as there were with the late organists Virgil Fox and E. Power Biggs a generation ago. What’s ironic is how the organ world establishment (represented mostly in the U.S. by the American Guild of Organists) now venerates Fox while Biggs is but a footnote. Though Carpenter is often dismissive and indifferent when asked about Fox, it’s always the envelope pushers who are remembered long after their time. It’s amusing to watch these perceptions play out — many U.S. organists, both in church and in academia, are almost contemptuous of Carpenter and only grudgingly acknowledge his technical prowess while Cowan is exalted as one of a precious few heirs apparent.

This isn’t just about hairstyles or even registrations (the settings by which organ sounds are varied throughout a piece or concert), for Cowan’s, while overall less brash than Carpenter’s, are not always as slavishly adhered to as some traditionalists insist (e.g. using only registrations that Bach had at his disposal in the 1700s when playing his works today).

Controversial, outspoken Carpenter is clearly having the overall bigger impact. Touted as “the world’s most visible organist” in the Kennedy Center program, it’s not much of an overstatement if at all. Though his D.C.-area debut at the Strathmore in April had an underwhelming turnout, he filled the orchestra section easily at the 2,400-seat Kennedy Center Concert Hall (the upper tiers were empty). Yes, the tickets were only $15 a piece, but a nearly full house to any organ recital in 2013 is seen as a triumph even if it’s free. Which Cowan’s was, though donations were accepted. The floor of First Baptist, which seats about 800, appeared to be about half full Sunday.

Carpenter’s at times brutal candor equals that of Joni Mitchell. Think for a minute about the overall rigidity of the classical world versus the pop world, and one can imagine the effect this has. Just last week, Carpenter mentioned in passing organ conventions and lamented anyone “unfortunate enough to have to go to one.” The AGO brass sees these as cheap shots and holds grudges accordingly. They’re sharpening their knives now in anticipation of his 2014 unveiling of a Marshall & Ogletree digital touring organ whose development Carpenter — who’s always polite in conversation and more nerdy than punk — supervised. He says it will revolutionize what an organist can do by not forcing an adaptation to site-specific pipe organs. They say there’s no way a virtual instrument can duplicate the richness of a true pipe organ (while Fox toured with electronic organs in the 1970s he never — to my knowledge — claimed they were sonically in the same league as a pipe organ).

There also may be unacknowledged resentment of the amount of world-wide press attention Carpenter gets, which is considerable, perhaps even unprecedented, for an organist. His fame is of rock star proportions in Japan and in parts of Europe.

Marketing and presentation are also factors. Carpenter has more media savvy, more acumen at presenting himself as a celebrity. Cowan — more classically handsome than Carpenter but not as trim and buff — looks like a professor (which he is; he heads the organ program at Rice University) who just happens to give recitals on weekends (which he does). Place their latest albums side by side and the photos alone illustrate the difference. Carpenter makes wise use of a stylist and put care into the overall presentations.  Cowan’s looks like an improperly lit snapshot superimposed over a boring church interior. Star power counts for something and Carpenter has it. It’s the difference between, say, a Jane Fonda and a Liv Ullmann. It’s no fluke that Fonda is the household name.

Cowan’s looks like an improperly lit snapshot superimposed over a boring church interior. Star power counts for something and Carpenter has it. It’s the difference between, say, a Jane Fonda and a Liv Ullmann. It’s no fluke that Fonda is the household name.

It was a bit startling then — with all this swirling around the classical music consciousness — how traditionally Carpenter opened his 89-minute Kennedy Center recital with the Bach “trio” Sonata No. 6 in G Major (BWV 530), especially the exquisite first movement (“Vivace”) which sounds as dainty as a finely embroidered doily but is wickedly difficult to play with three contrapuntal lines swirling about (right hand on one manual, left hand another and the pedals/feet sharing an equally complex third voice). Carpenter took it at a very brisk tempo and pulled it off with expected aplomb. He used more pedal 16-foot stops than Bach would have had in his era, but the flute- and principle-heavy registration was not unorthodox. His closing self-added ornamentation — not an unusual thing to do — was a well-placed flourish at the end of a musical sentence.

The registrations were slightly more daring in the languid second movement (“Lento”), which had breathy, deep 16-foot moderately soft pedal stops over which Carpenter wove the melody with slightly louder reed stops. He took the (“Allegro”) third movement in a more traditional manner, giving its lovely contrapuntal interplay the stately feel of a fanfare.

One of the challenges any organist faces is blending the four types of sounds the instrument produces — generally the flutes and strings are softer than the principles and reeds. Building a gradual increase in volume by changing registration can be tough, but Carpenter did so brilliantly (Cowan is also a master of this) in his Etude from the prelude of Bach’s “Cello Suite No. 1,” a piece he also used as an encore in homage to Yo-Yo Ma (who also played that night) during his previous Kennedy Center appearance. It started with a delicate, chiffy pedal solo but climaxed with loud grandiosity.

Its inclusion was a surprise — Carpenter added it after saying he wasn’t finished learning his new composition “Music for an Imaginary Film” which was slated to close the program. In its place he also added his own “Love Song No. 2,” a lush, string-laden contemporary piece he rightly called a palate cleanser.

He closed the first half of the program with an adaptation of Mozart’s “Sonata in D Major” (K.284), which had constant-yet-deft color shifts. He made clever use of some of the organ’s more outré stops with playful little honks and echoes in the third movement, several of which elicited light chuckles from the crowd.

In the second half, Dupre’s “Variations on a Noel, Op. 20” came roaring to life in a way simply not possible when Carpenter performed the piece (one of only two duplicated) at the Strathmore. It was effective there, but if it were possible to hear the two performances side by side, no further arguments would be needed for the sonic chasm that exists between a grand instrument like the Rubenstein organ and the one-dimensional Rodgers electronic Carpenter played there. He performed like a demon that night — changing registrations like a mad scientist (perhaps necessitated by the need for variation on the much smaller organ) — but hearing him at the Kennedy Center was exponentially more satisfying. The Dupre Noel set is a perfect piece for Carpenter giving him enough deliciously weird variations (most of it’s about as warm and Christmasy as a Quentin Tarantino film) to play with. He upped the ante with equally diabolical registration choices, at times summoning what sounded like the gates of hell with the full power of the organ.

If there was any disappointment to the evening, it was only slightly in the sequencing. Building an impossibly overstated introduction to a transcription of Scriabin’s (originally for piano) “Sonata No. 4, Op. 30,” (“I can’t imagine music more uplifting and absolutely affirming of humanity than this,” he said), the piece (originally slated to close the first half) was too dense and abstract to be a wholly satisfying finish to the evening. The heroic, playful and jaunty Tchaikovsky “Scherzo” from “Symphony No. 6,” which Carpenter practically galloped his way through — you can see the music coursing through his gyrations — and used to open the second half, would have been a better choice. Yes, it’s the more ear-friendly and obvious crowd pleasing-kind-of piece, but that’s not why I suggest this. The epic full organ registration with which Carpenter played it sounded so rich and symphonic, one could not possibly fathom that all this sound was coming from one human and one organ. Closing with it would have showed both he and the organ off in the most staggering light.

Two encores — Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” and the bon mot “Stars and Stripes Forever” were everything encores should be: playful, fun, short and easy on the ears.

Cowan, too, opened his 94-minute recital with Bach, hardly surprising but fine. His “Toccata in E Major (BWV 566)” got things off to a solid but far-from-earth-shattering manner. Cowan’s almost non-existent body movement while playing combined with the hardly daring opening — though admittedly no more traditional than Carpenter’s — initially had me fearing we might be in for a long afternoon. I knew Carpenter would shake things up; having not heard Cowan live before, I wasn’t sure where he was heading. Yes, there was a program but the pieces were not, for the most part, staples of the organ repertoire.

To say there was nothing to fear is a vast understatement. Cowan quickly got things bubbling with an utterly transfixing performance of Jean Roger-Ducasse’s “Pastorale,” which he played exquisitely and registered imaginatively and seamlessly.

Ironically considering the sacred setting, the devil was summoned twice — in Rachel Laurin’s playful “Beelzebub’s Laugh,” an etude that Cowan masterfully registered so that a three-note descending melodic line that was repeated many times darted around from the Chancel to the Gallery organs so quickly it was nearly dizzying. Satan was further evoked in an arrangement of Liszt’s famous “Mephisto Waltz No. 1,” a staggerlingly virtuosic piece with which Cowan clearly had fun.

Leo Sowerby’s maddeningly difficult “Pageant,” which opens with a lengthy pedal solo that descends in rapid chromatic lines, found Cowan exhibiting every bit as much elaborate foot work as Carpenter famously exhibits in his transcription of Chopin’s “Revolutionary Etude,” a massive YouTube hit he curiously no longer plays live. While nobody’s calling it a talent competition, the two are clearly equals in technical ability and overall musicianship.

Cowan’s recital came to a glorious and stately climax with Max Reger’s monumental Fantasy on the Chorale “Wachet auf, ruft uns die stimme,” (Op. 52, No. 2), a dramatic interpretation of the famous Advent hymn (“Sleepers Awake”) that breaks into a daring four-part fugue and ends with a towering procession on which Cowan brought the magnificent new organ to full flower. This is another spot that separates the men (state-of-the-art pipe organs) from the boys (the best electronics available): the triple-forte passages on a great organ like the Austin are unquestionably loud but not in an ear-splitting, siren kind-of way. It’s loud in a lush way that still manages to be easy on the ear and with a depth of quality and detail no speaker can summon — nearly the same difference as one perceives optically between a sunset in nature versus one seen on a high definition TV screen. Only having experienced it in nature, can one fully appreciate the difference.

Cowan’s well-deserved encore was another pedal workout — George Thalben-Ball’s “Variations on a Theme by Paganini,” which found him achieving almost unfathomable legato-yet-uber-fast melodic passages on the pedalboard alone.

As one might imagine, these recitals together made for heady experiences. One savored them as one might great multi-course meals from two top-tier chefs working with the crème de la crème of fresh ingredients on two different nights. It’s impossible to overstate their sumptuousness. No degree of rhapsodic waxing feels sufficient.

First Baptist’s organ — some tuning issues evident at Schreiber’s recital all worked out as expected — is not necessarily sonically any richer than that of the Rubenstein organ; it simply has a substantially broader range of sound, which Cowan made abundant use of and of which Carpenter no doubt would have done as well had he performed there. First Baptist’s fills the space perhaps a bit more thoroughly than the Rubenstein, which, though possessing sonic heft, never quite flirts with rumbling the architecture. You don’t quite feel it the way you feel the enveloping Austin.

It was especially noticeable on the Reger during which Cowan spent lengthy measures savoring the organ’s soft 32-foot pedal stops, which rumbled and chiffed — slightly differently even from tone to tone — like warm signals from beneath the ocean floor. Elsewhere, soft string stops in the manuals sounded as warm as finely ground spun sugar. The two magnificent sets of “trompette-en-chamade” stops (one rank softer and in the English trumpet tradition; the other more blaring and French) were repeatedly woven into the selections and used generously but wisely, ringing out from the church balcony where they’re placed.

Perhaps realizing they both had rare opportunities to introduce many to new instruments, Carpenter and Cowan both clearly took delight in showcasing both their own talent and that of the organ builders.

One salivates at the thought of what these two geniuses will do in the coming years, not to mention all the great organists Washingtonians and visitors will enjoy on these stupendous new instruments.

Blade Features Editor Joey DiGuglielmo may be reached at [email protected].

Carpenter’s set list

Sonata No. 6 in G Major (BWV 530) (Bach)

1. Vivace

2. Lento

3. Allegro

4. Etude on the Prelude from Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major (BWV 1007) (Bach)

5. Love Song No. 2 (Carpenter)

Sonata in D Major (K. 284) (Mozart)

6. Allegro

7. Rondo and Polonaise

8. Theme with Variations

Intermission

9. Scherzo from Symphony No. 6 “Pathetique” (Tchaikovsky)

10. Variations on a Noel (Op. 20) (Dupre)

Sonata No. 4 (Op. 30) (Scriabin)

11. Andante

12. Prestissimo Volando

Encores

13. Minute Waltz (Chopin)

14. Stars and Stripes Forever (Sousa)Cowan’s set list:

1. Toccata in E Major (BWV 566) (Bach)

2. Pastorale (Roger-Ducasse)

3. Beelzebub’s Laugh (Etude-Caprice, Op. 66) (Laurin)

4. Pageant (Sowerby)

Intermission

5. Mephisto Waltz No. 1 (Liszt)

6. Fantasy on the chorale “Wachet auf, ruft uns die stimme” (Op. 52, No. 2) (Reger)

Encore

7. Variations on a Theme by Paganini: a Study for the Pedals (Thalben-Ball)

Movies

Radical reframing highlights the ‘Wuthering’ highs and lows of a classic

Emerald Fennell’s cinematic vision elicits strong reactions

If you’re a fan of “Wuthering Heights” — Emily Brontë’s oft-filmed 1847 novel about a doomed romance on the Yorkshire moors — it’s a given you’re going to have opinions about any new adaptation that comes along, but in the case of filmmaker Emerald Fennell’s new cinematic vision of this venerable classic, they’re probably going to be strong ones.

It’s nothing new, really. Brontë’s book has elicited controversy since its first publication, when it sparked outrage among Victorian readers over its tragic tale of thwarted lovers locked into an obsessive quest for revenge against each other, and continuing to shock generations of readers with its depictions of emotional cruelty and violent abuse, its dysfunctional relationships, and its grim portrait of a deeply-embedded class structure which perpetuates misery at every level of the social hierarchy.

It’s no wonder, then, that Fennell’s adaptation — a true “fangirl” appreciation project distinguished by the radical sensibilities which the third-time director brings to the mix — has become a flash point for social commentators whose main exposure to the tale has been flavored by decades of watered-down, romanticized “reinventions,” almost all of which omit large portions of the novel to selectively shape what’s left into a period tearjerker about star-crossed love, often distancing themselves from the raw emotional core of the story by adhering to generic tropes of “gothic romance” and rarely doing justice to the complexity of its characters — or, for that matter, its author’s more complex intentions.

Fennell’s version doesn’t exactly break that pattern; she, too, elides much of the novel’s sprawling plot to focus on the twisted entanglement between Catherine Earnshaw (Margot Robbie), daughter of the now-impoverished master of the titular estate (Martin Clunes), and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi), a lowborn child of unknown background origin that has been “adopted” by her father as a servant in the household. Both subjected to the whims of the elder Earnshaw’s violent temper, they form a bond of mutual support in childhood which evolves, as they come of age, into something more; yet regardless of her feelings for him, Cathy — whose future status and security are at risk — chooses to marry Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif), the financially secure new owner of a neighboring estate. Heathcliff, devastated by her betrayal, leaves for parts unknown, only to return a few years later, with a mysteriously-obtained fortune. Imposing himself into Cathy’s comfortable-but-joyless matrimony, he rekindles their now-forbidden passion and they become entwined in a torrid affair — even as he openly courts Linton’s naive ward Isabella (Alison Oliver) and plots to destroy the entire household from within. One might almost say that these two are the poster couple for the relationship status “it’s complicated.” and it’s probably needless to say things don’t go well for anybody involved.

While there is more than enough material in “Wuthering Heights” that might easily be labeled as “problematic” in our contemporary judgments — like the fact that it’s a love story between two childhood friends, essentially raised as siblings, which becomes codependent and poisons every other relationship in their lives — the controversy over Fennell’s version has coalesced less around the content than her casting choices. When the project was announced, she drew criticism over the decision to cast Robbie (who also produced the film) opposite the younger Elordi. In the end, the casting works — though the age gap might be mildly distracting for some, both actors deliver superb performances, and the chemistry they exude soon renders it irrelevant.

Another controversy, however, is less easily dispelled. Though we never learn his true ethnic background, Brontë’s original text describes Heathcliff as having the appearance of “a dark-skinned gipsy” with “black fire” in his eyes; the character has typically been played by distinctly “Anglo” men, and consequently, many modern observers have expressed disappointment (and in some cases, full-blown outrage) over Fennel’s choice to use Elordi instead of putting an actor of color for the part, especially given the contemporary filter which she clearly chose for her interpretation for the novel.

In fact, it’s that modernized perspective — a view of history informed by social criticism, economic politics, feminist insight, and a sexual candor that would have shocked the prim Victorian readers of Brontë’s novel — that turns Fennell’s visually striking adaptation into more than just a comfortably romanticized period costume drama. From her very opening scene — a public hanging in the village where the death throes of the dangling body elicit lurid glee from the eagerly-gathered crowd — she makes it oppressively clear that the 18th-century was not a pleasant time to live; the brutality of the era is a primal force in her vision of the story, from the harrowing abuse that forges its lovers’ codependent bond, to the rigidly maintained class structure that compels even those in the higher echelons — especially women — into a kind of slavery to the system, to the inequities that fuel disloyalty among the vulnerable simply to preserve their own tenuous place in the hierarchy. It’s a battle for survival, if not of the fittest then of the most ruthless.

At the same time, she applies a distinctly 21st-century attitude of “sex-positivity” to evoke the appeal of carnality, not just for its own sake but as a taste of freedom; she even uses it to reframe Heathcliff’s cruel torment of Isabella by implying a consensual dom/sub relationship between them, offering a fragment of agency to a character typically relegated to the role of victim. Most crucially, of course, it permits Fennell to openly depict the sexuality of Cathy and Heathcliff as an experience of transgressive joy — albeit a tormented one — made perhaps even more irresistible (for them and for us) by the sense of rebellion that comes along with it.

Finally, while this “Wuthering Heights” may not have been the one to finally allow Heathcliff’s racial identity to come to the forefront, Fennell does employ some “color-blind” casting — Latif is mixed-race (white and Pakistani) and Hong Chau, understated but profound in the crucial role of Nelly, Cathy’s longtime “paid companion,” is of Vietnamese descent — to illuminate the added pressures of being an “other” in a world weighted in favor of sameness.

Does all this contemporary hindsight into the fabric of Brontë’s epic novel make for a quintessential “Wuthering Heights?” Even allowing that such a thing were possible, probably not. While it presents a stylishly crafted and thrillingly cinematic take on this complex classic, richly enhanced by a superb and adventurous cast, it’s not likely to satisfy anyone looking for a faithful rendition, nor does it reveal a new angle from which the “romance” at its center looks anything other than toxic — indeed, it almost fetishizes the dysfunction. Even without the complex debate around Heathcliff’s racial identity, there’s plenty here to prompt purists and revisionists alike to find fault with Fennell’s approach.

Yet for those looking for a new window into to this perennial classic, and who are comfortable with the radical flourish for which Fennell is already known, it’s an engrossing and intellectually stimulating exploration of this iconic story in a new way — and for cinema fans, that’s more than enough reason to give “Wuthering Heights” a chance.

Crimsyn and Tatianna hosted the new weekly drag show Clash at Trade (1410 14th Street, N.W.) on Feb. 14, 2026. Performers included Aave, Crimsyn, Desiree Dik, and Tatianna.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

Theater

Magic is happening for Round House’s out stage manager

Carrie Edick talks long hours, intricacies of ‘Nothing Up My Sleeve’

‘Nothing Up My Sleeve’

Through March 15

Round House Theatre

4545 East-West Highway

Bethesda, Md. 20814

Tickets start at $50

Roundhousetheatre.org

Magic is happening for out stage manager Carrie Edick.

Working on Round House Theatre’s production of “Nothing Up My Sleeve,” Edick quickly learned the ways of magicians, their tricks, and all about the code of honor among those who are privy to their secrets.

The trick-filled, one-man show starring master illusionist Dendy and staged by celebrated director Aaron Posner, is part exciting magic act and part deeply personal journey. The new work promises “captivating storytelling, audience interaction, jaw-dropping tricks, and mind-bending surprises.”

Early in rehearsals, there was talk of signing a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) for production assistants. It didn’t happen, and it wasn’t necessary, explains Edick, 26. “By not having an NDA, Dendy shows a lot of trust in us, and that makes me want to keep the secrets even more.

“Magic is Dendy’s livelihood. He’s sharing a lot and trusting a lot; in return we do the best we can to support him and a large part of that includes keeping his secrets.”

As a production assistant (think assistant stage manager), Edick strives to make things move as smoothly as possible. While she acknowledges perfection is impossible and theater is about storytelling, her pursuit of exactness involves countless checklists and triple checks, again and again. Six day weeks and long hours are common. Stage managers are the first to arrive and last to leave.

This season has been a lot about learning, adds Edick. With “The Inheritance” at Round House (a 22-week long contract), she learned how to do a show in rep which meant changing from Part One to Part Two very quickly; “In Clay” at Signature Theatre introduced her to pottery; and now with “Nothing Up My Sleeve,” she’s undergoing a crash course in magic.

She compares her career to a never-ending education: “Stage managers possess a broad skillset and that makes us that much more malleable and ready to attack the next project. With some productions it hurts my heart a little bit to let it go, but usually I’m ready for something new.”

For Edick, theater is community. (Growing up in Maryland, she was a shy kid whose parents signed her up for theater classes.) Now that community is the DMV theater scene and she considers Round House her artistic home. It’s where she works in different capacities, and it’s the venue in which she and actor/playwright Olivia Luzquinos chose to be married in 2024.

Edick came out in middle school around the time of her bat mitzvah. It’s also around the same time she began stage managing. Throughout high school she was the resident stage manager for student productions, and also successfully participated in county and statewide stage management competitions which led to a scholarship at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) where she focused on technical theater studies.

Edick has always been clear about what she wants. At an early age she mapped out a theater trajectory. Her first professional gig was “Tuesdays with Morrie” at Theatre J in 2021. She’s worked consistently ever since.

Stage managing pays the bills but her resume also includes directing and intimacy choreography (a creative and technical process for creating physical and emotional intimacy on stage). She names Pulitzer Prize winning lesbian playwright Paula Vogel among her favorite artists, and places intimacy choreographing Vogel’s “How I learned to Drive” high on the artistic bucket list.

“To me that play is heightened art that has to do with a lot of triggering content that can be made very beautiful while being built to make you feel uncomfortable; it’s what I love about theater.”

For now, “Nothing Up My Sleeve” keeps Edick more than busy: “For one magic trick, we have to set up 100 needles.”

Ultimately, she says “For stage managers, the show should stay the same each night. What changes are audiences and the energy they bring.”

-

Theater5 days ago

Theater5 days agoMagic is happening for Round House’s out stage manager

-

Baltimore3 days ago

Baltimore3 days ago‘Heated Rivalry’ fandom exposes LGBTQ divide in Baltimore

-

Real Estate3 days ago

Real Estate3 days agoHome is where the heart is

-

District of Columbia3 days ago

District of Columbia3 days agoDeon Jones speaks about D.C. Department of Corrections bias lawsuit settlement