Arts & Entertainment

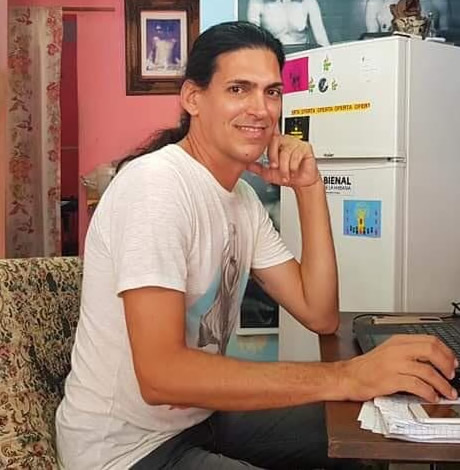

A non-binary Cuban artist is born again in Spain

Nonardo Perea suffered persecution in his homeland

Nonardo Perea lives in Michel’s body. He uses it at will to be vulgar, angelic or diabolical, male or female. Nonardo can be whatever he wants. Michel, shy and withdrawn, hides behinds that alter ego that lends him his face and hands to show the world his claims as an artist.

Nonardo is an invention that comes to life in photographs, video art, performances, stories, installations, journalistic articles, ceramics, and whatever other format is possible, since Nonardo long ago lost any limits. His mind lost that ability as he reinvented himself as an empirical artist, as no one ever gave him the opportunity to attend art school.

He has been greatly misunderstood, mainly because his pieces overflowed with eroticism and Cuba is still too prudish to appreciate his queer art and his other works the regime has labeled as “politically incorrect.” Michel and Nonardo were discriminated against by society and the dictatorship that governs the country and represses anyone who does not agree with its dogmas.

Nonardo nevertheless overcame those barriers and began creating, without anyone’s guidance. He was first a writer and received some tools once he graduated from the Onelio Jorge Cardoso Literary Training Center in Havana. He won several competitions, such as the 2017 Franz Kafka Prize for his work “Los amores ejemplares” and the 2012 Félix Pita Rodríguez Prize for the novel “Donde el diablo puso la mano.”

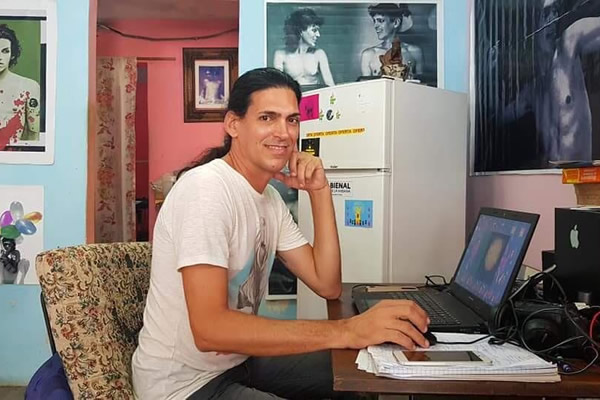

In the visual arts, where he is usually very restless, he won the third prize for photography at the GendErotica Festival for “La casa por la ventana 2014” with his Vulgarmente Clásica project. He participated in the Bienal 00, organized by independent artists, with his “En la cama con Nonardo” project and presented Vulgarmente Clásica at Madrid’s La Neomudéjar Museum in 2019.

Nonardo belongs to the San Isidro Movement, a group of independent artists and intellectuals who fight for a democratic Cuba. That battle has also been fought through his art and in pursuit of LGBTQ rights, such as marriage and adoption rights for same-sex couples, and an end to gender violence that remains a problem on the island.

Due to his work and political activism for a truly democratic Cuba, Nonardo suffered police harassment and Cuban state security agents threatened him with jail. Fearing for his life, he took refuge in Spain, a country where he feels he has been reform and from which he speaks with the Washington Blade.

WASHINGTON BLADE: Those who follow your art on social networks and off of them know you as Nonardo, but few know that your real name is Michel. How and why was Nonardo Perea born?

NONARDO PEREA: I remember starting my writing career and I needed another name that was not so common. I did a big search and I didn’t like any of them. I wanted a unique name if possible. One afternoon I was sitting in the living room of my house with my father and I told him about the need for a name. It was he who proposed Nonardo. At first it sounded a bit ugly to me, but then with Perea it seemed a little better. It had strength. I liked it because it began with “no”, denial, and was followed by “nardo”, flower, that is, Nonardo had a lot to do with me. Since then I started using it for all of my work, both literary and audiovisual.

BLADE: How does your artistic training take into account that you are an empirical creator?

PEREA: My artistic creation from the beginning was always very complicated, taking into account that I had to abandon my studies at an early age for inclusion reasons, so I have no academic training; then add to that that I am a very obvious gay. At one point in my teens I was seen as a person who was too feminine. The fact of looking like a woman was a problem when trying to fit in a macho and homophobic society. Where I first tried to break through was in writing. I started by attending literary workshops, where I won several contests quite quickly. I was never exempt from criticism and rejection of the themes that my narrations addressed, which almost always focused on LGBTQ issues and dirty realism. Many times I felt that being the way I am made many uncomfortable. But despite the rejections and bad times that I lived in various periods of my life, I continued doing narrative, and I also began to write articles about social issues for the Havana Times digital newspaper. Then, over time, I had the opportunity to apply to a video journalism workshop in Prague organized by the People in Need organization, and thanks to a woman I love very much, Clara González, who saw some potential in me, I was accepted to participate in the course, in which I learned some video editing, and received help with equipment that helped me to start doing audiovisual work with better quality. All my creative works have been done empirically, and above all I am an artist who works based on improvisation.

BLADE: You have ventured into artistic genres as different as writing, journalism and acting. How do you define yourself as an artist and why?

PEREA: I am a person who cannot be inactive. I spend every day of my life thinking about doing something new. Sometimes I have so many things on my mind, and the fact that I can’t do everything I want to do makes me feel a bit frustrated. I have no words to define myself, I can only say that in some way my creative processes have helped me to cope with the life that I had to live, everything I have done and do has served as a way of escape from reality and everyday life, I could no longer live without creating.

BLADE: In a recent interview you precisely declared that your art was a process of liberating yourself. What exactly do you free yourself from when you create?

PEREA: I free myself from the day-to-day, the everyday, my fears and censorship.

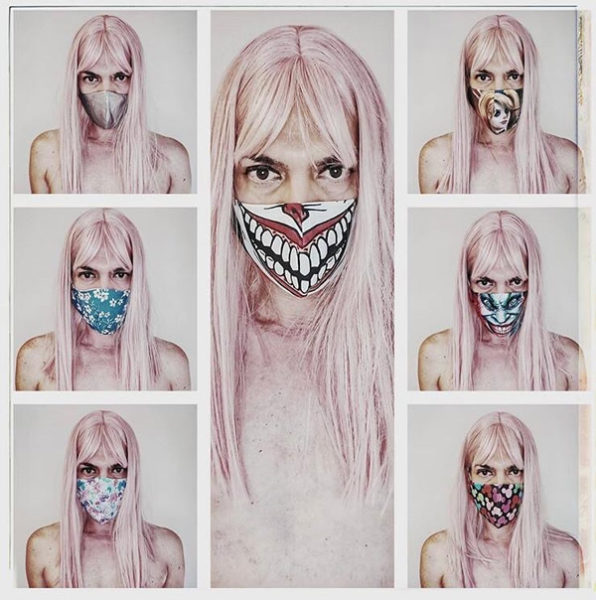

BLADE: In most of your visual works you work with your own image. Why?

PEREA: I use myself as an artistic object because in Cuba I lived in solitude for a long time. I somehow isolated myself and created a space of comfort in my home, a place where I felt more free. The confinement somehow helped me to stay away from society that did not tire of making me feel bad about my obvious homosexual condition in much of my youth. My literary proposals and art in general, on the other hand, were not taken into account. I always perceived that most people underestimated me, and proposing someone to collaborate with me on erotic photographs without receiving anything in return was complicated, and still is. I have control over my body. If I want to undress in a photo or in a video, even if I feel sorry, I strip myself of complexes and do it. If I want to take a photograph that is too vulgar, I also do it. I do not have to request permission from anyone to do so. I don’t put up barriers. I take a risk, then I think that they say what they want. I understand that I am doing a job where I express my personal and social problems, as a human being.

BLADE: You identify yourself as an androgynous person. How many difficulties has that brought you considering that you have lived most of your life and developed your work in Cuba, a country where macho and homophobic ideals still predominate?

PEREA: I consider myself a non-binary androgynous person, because I do not identify with any sex. I can feel at ease as a girl as well as a boy. I have no problem with male or female pronouns. I do not like to victimize myself, but I can tell you that the road has been very difficult, and it has been not only for me, but for many other gays and lesbians who have chosen not to hide their sexual identity in their lives and have had to fight against the world. Being who I am in Cuba has not helped me much in terms of being able to be recognized for my work, but being who I am has helped me to strengthen myself and to understand that I do not need the approval of any institution to continue creating. I am a Cuban artist and like it or not, a large part of my work was created in Cuba.

BLADE: Many Cuban artists prefer to separate their creations from politics and even refuse to give their true judgment on the situation on the island. However, your work has a high dose of activism against the dictatorship and in defense of LGBTQ rights. What consequences, professional and personal, has being an artist labeled by the Cuban regime as “counterrevolutionary” brought you?

PEREA: The main consequence is that I had to go into exile; leave the country where I was born, abandon my mother and family, my friends, my dogs and a lifetime. But I think it had to be that way. There was no other way than to say goodbye, because under no circumstances was I going to allow my creative processes to stop, and above all I was going to continue doing my activism. I know that perhaps I was not going to be able to withstand so much pressure from state security agents, who wanted me to collaborate with them to expose my colleagues from the San Isidro Movement. If I returned to Cuba right now, I don’t know what my life would have been like from that moment on. If being a counterrevolutionary means saying what I think, and being in favor of oppressed minorities, and being against a dictatorship that has left Cuba and its people in a nameless misery for 61 years, then I am a counterrevolutionary and with great honor. I have nothing for which to thank that country, where I was always seen as a freak, and what little I got was thanks to my effort and dedication, because while in Cuba I received criticism and obstacles for everything, for this reason they are collecting what they sowed with me, they do not expect roses from me.

BLADE: In Cuba, to be accepted as part of the official LGBTQ movement you have to share the ideology of the dictatorship, the same one that put equal marriage to a popular vote and represses independent activists. In your opinion, what are the dangers of “politicizing” the struggle of the Cuban gay movement?

PEREA: The danger is in seeing how it becomes politicized. While in Cuba, I never stopped going to the marches staged by CENESEX (the National Center for Sexual Education) and I will not forget how Mariela Castro (CENESEX’s director and the daughter of former Cuban President Raúl Castro) herself politicized those mini-carnival marches with slogans in favor of the five spies imprisoned in the Empire (a reference to the U.S.), and with cries of “socialism yes and homophobia no.” I do not remember seeing any gay or lesbian carrying a sign demanding equal marriage, or demanding freedoms, or a law against gender violence. It is really pathetic considering that the system itself is the number one cause of the persistence of homophobia and constant abuse of people from the community, mainly transgender people, in Cuba, a country where your rights are constantly violated, either because of race or sexual orientation. Those marches were politicized by CENESEX itself in favor of a supposed socialism, which has never worked and will never work because that is a hybrid between communism and underdeveloped capitalism, and we all know that it is nothing other than a dictatorship, and of the crudest in history because it has managed to last for 61 years. If Mariela Castro and all her loyal followers politicize the march for their benefit, I don’t see why the community cannot independently arm its own fight in favor of the most basic rights of the LGBTQ community in Cuba.

BLADE: In what way has the forced exile that you have faced in Spain changed your work?

PEREA: Right now I continue to do what I want to do, regardless of being in Spain. I still feel that I am in Cuba. My vision as an artist has not changed much. I’ve only been here a year and seven months, although I believe that wherever I am, in some way my work will be linked to that of the island because I have not yet cut that umbilical cord that links me to the place where I was born and took my first steps. It is true that one acquires other mechanisms of creation and invoicing in the work while abroad, but at the moment I do not think that the focus of my work has changed much because of being in another country. Of course, here in Europe there are other problems that I may be able to take advantage of, but be that as it may, they will be appreciated from the perspective of an exiled Latin American artist.

BLADE: On a personal level, what has it been like to be a gay immigrant in Europe?

PEREA: I am very grateful for Spain, mainly for Madrid, which is the place where I have lived since I arrived in 2019. At the moment, I have not felt discriminated against because of my sexual orientation or because I am a foreigner. I have received emotional and legal support from the NGO Rescate, which welcomed me and where I have received the care that I never had in my own country. With all the social and political problems that may exist, it is in this country where I have somehow been able to know what true freedom is.

BLADE: What can we expect from Nonardo Perea in the near future?

PEREA: I am in another difficult moment in my life right now, because I cannot find a job, and I do not receive any money for my artistic work, so what I do is for the love of art and because I cannot stop building my own world. The COVID situation has managed to make things more difficult, not only for me but for everyone, but taking into account that I am an exile and that I have been here for a short time, it is very complicated. Even so, I eventually continue to make video art for the Vulgarmente Clásica audiovisual project, which I have been doing for several years. And more recently I started with a new project, “Maricón Tropical: Living in Madrid”, this one is a bit more comprehensive not to call it ambitious because I insert various artistic manifestations: Performance, audiovisual, literature, drawing and photography, and it is focused on my new life as an exile in Madrid, everything seen from a self-referential point of view, as are almost all my proposals.

BLADE: If you had to create a work that describes your life right now, what would it be like?

PEREA: I consider that my life, my true life, has started now, what it was before was not. For the purposes I was born on March 19, 2019, when I set foot in Spain. All the past is left behind. I want to imagine that the past was a bad dream. My “Maricón Tropical: Living in Madrid” project is a work that somehow reflects that past, which is unfortunately impossible to forget and it is also good that people know what that other life was like, but I focus more on the present, my current problems as a person who faces a new life as an adult who feels like a newborn. I can only tell you that my life’s work is in progress.

Out & About

Plan your wedding the LGBTQ way

Washington D.C. LGBTQ+ Wedding Expo scheduled for Sunday

Rainbow Wedding Network will host “Washington D.C. LGBTQ+ Wedding Expo” on Sunday, March 1 at 12:30 p.m.

Guests can meet and mingle with a curated selection of LGBTQ-welcoming wedding professionals from across the region, each ready to help bring your vision to life, and spend a beautiful afternoon exploring everything they need to create a celebration that reflects them.

There will be a relaxed, self-guided look at the Watergate’s spaces and amenities, savor signature cocktails and delicious tasting samples, and connect with other couples who are on the same journey.

Visit Eventbrite to reserve a spot.

Friday, February 27

Center Aging Monthly Luncheon With Yoga and Drag Bingo will be at 12 p.m. at the DC Center for the LGBT Community. Email Mac at [email protected] if you require ASL interpreter assistance, have any dietary restrictions, or questions about this event.

Go Gay DC will host “LGBTQ+ Community Happy Hour Meetup” at 7 p.m. at Freddie’s Beach Bar and Restaurant. This is a chance to relax, make new friends, and enjoy happy hour specials at this classic retro venue. Attendance is free and more details are available on Eventbrite.

Trans Discussion Group will be at 7 p.m. on Zoom. This group is intended to provide an emotionally and physically safe space for trans people and those who may be questioning their gender identity/expression to join together in community and learn from one another. For more details, email [email protected].

Saturday, February 28

Go Gay DC will host “LGBTQ+ Community Brunch” at 11 a.m. at Freddie’s Beach Bar & Restaurant. This fun weekly event brings the DMV area LGBTQ+ community, including allies, together for delicious food and conversation. Attendance is free and more details are available on Eventbrite.

The DC Center for the LGBT Community will host “Sunday Supper on Saturday” at 2 p.m. It’s more than just an event; it’s an opportunity to step away from the busyness of life and invest in something meaningful, and enjoy delicious food, genuine laughter, and conversations that spark connection and inspiration. For more details, visit the Center’s website.

Black Lesbian Support Group will be at 1 p.m. on Zoom. This is a peer-led support group devoted to the joys and challenges of being a Black lesbian. You do not need to be a member of the Beta Kappa Chapter or the Beta Phi Omega Sorority in order to join, but they do ask that you either identify as a lesbian or are questioning that aspect of your identity.Send an email to [email protected] to receive the zoom link.

Sunday, March 1

LGBTQ+ Community Coffee and Conversation will be at 12 p.m. at As You Are. This event is for people looking to make more friends and meaningful connections in the LGBTQ community. Attendance is free and more details are available on Eventbrite.

Monday, March 2

“Center Aging: Monday Coffee Klatch” will be at 10 a.m. on Zoom. This is a social hour for older LGBTQ+ adults. Guests are encouraged to bring a beverage of choice. For more information, contact Adam ([email protected]).

Tuesday, March 3

Universal Pride Meeting will be at 7 p.m. on Zoom. This group seeks to support, educate, empower, and create change for people with disabilities. For more details, email [email protected].

Wednesday, March 4

Job Club will be at 6 p.m. on Zoom upon request. This is a weekly job support program to help job entrants and seekers, including the long-term unemployed, improve self-confidence, motivation, resilience and productivity for effective job searches and networking — allowing participants to move away from being merely “applicants” toward being “candidates.” For more information, email [email protected] or visit www.thedccenter.org/careers.

Center Aging Women’s Social and Discussion Group will be at 6 p.m. on Zoom. This group is a place where older LGBTQ+ women can meet and socialize with one another. There will be discussion, activities, and a chance for guests to share what they want future events to include. For more information, email [email protected].

Thursday, March 5

The DC Center’s Fresh Produce Program will be held all day at the DC Center for the LGBT Community. People will be informed on Wednesday at 5 p.m. if they are picked to receive a produce box. No proof of residency or income is required. For more information, email [email protected] or call 202-682-2245.

Virtual Yoga Class will be at 7 p.m. on Zoom. This free weekly class is a combination of yoga, breathwork and meditation that allows LGBTQ+ community members to continue their healing journey with somatic and mindfulness practices. For more details, visit the DC Center’s website.

a&e features

Transmission DC breathes new life into a storied sound space

A fresh home for boundary-pushing culture on H Street

Late last year, phoenix-style, a fresh home for boundary-pushing culture arose on the H Street corridor. Transmission DC – a queer, trans, and POC-owned, operated, and centered community-focused venue – powered on in the former home to the Rock & Roll Hotel (famously, not a hotel, but very much rock & roll). Transmission (1353 H St., N.E.) arrives secure in its mandate – or even birthright – to provide a place to celebrate creativity and music through a lens of inclusivity and respect.

Transmission’s team brings experience, but also representation. Owners/partners Kabir Khanna (who is also programming director), Katii B, Ellie McDyre, and Kelli Kerrigan together previously managed 618 productions, a venue in Chinatown, crafting “some of D.C.’s freakiest parties, raves, and mosh pits” they note.

They packed up operations last fall to a space curated specifically for D.C.’s underground music and culture scene, building their efforts in Chinatown to bring in more fans in queer and POC circles.

Transmission, Khanna points out, is built on DIY values. In the music scene, DIY means that promoters and organizers – often disconnected from the mainstream and part of marginalized communities – build shows and programs collaboratively, but independently from institutions, supporting each other as smaller, independent venues close. Here, Transmission aims to ensure that those putting together these underground inclusive shows have a more permanent and stable home, can have access to resources, and can provide more sustainable income to artists. “We’re trying to get more people to support and enjoy the music, and also give artists and organizers within the DIY community more structure and a larger cut,” says Khanna.

Khanna also notes that Transmission operates “under the principles of safety, inclusivity, and respect.” McDyre added that even at venues that claim inclusivity, that statement might not take place in practice. We’re “not just pitting up a rainbow flag,” says McDyre, but as some of the owners are trans and POC, audiences can see themselves reflected at the top.

Much like the DIY nature of the music community, the Transmission owners brought a DIY ethos to turning around their space.

In March 2020 – the height of COVID lockdowns – Rock & Roll Hotel suddenly shuttered, though not due to the pandemic; instead, the venue claimed that decreasing sales and increasing competition led to the closure. For 14 years, it was the central spot for cheap beer and lesser-known and celebrated acts. The space stood vacant for more than five years, until Transmission turned the power back on.

“When we got into the space, it was effectively abandoned for years,” says Khanna. “There was a ton of mold, and paint primer covering all surfaces. It was nearly falling apart.” Khanna noted that many music venues like this one, regardless of how well it was maintained, “get the shit kicked out of it,” given the nature of shows. The team called in mold removal contractors, ripped up most of the floorboards, and started fresh.

Transmission’s first floor is styled as a stripped-down black box: the better to take in the music. “It’s minimal on purpose to act as a canvas for set design and music,” without a specific aesthetic, says Khanna. Moving upstairs, the second floor has been opened up, removing some walls, and now has a larger dance area than the first floor. Beyond the first two performance levels, and a holdover from Rock & Roll Hotel, is the rooftop. Though without a stage, the rooftop space is filled with murals splashed across the walls, with a full bar. Transmission’s current capacity is 496, but the team is looking to grow that number. Transmission will also leverage the full kitchen that Rock & Roll Hotel operated, bringing in Third Hand Kitchen to offer a variety of food, including vegan and vegetarian options.

Khanna pointed out an upcoming show reflective of Transmission’s inclusive ethos: Black Techo Matters on Feb. 27. The event is set to be “a dynamic, collaborative night of underground electronic music celebrating Black History Month.” Khanna says that techno came from Black music origins, and this event will celebrate this genesis with a host of artists, including DJ Stingray 313, Carlos Souffront, and Femanyst.