Arts & Entertainment

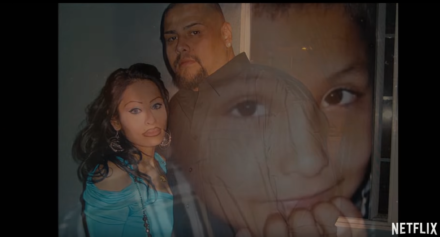

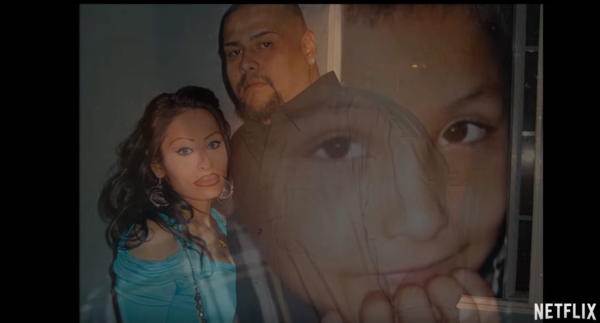

Netflix revisits ‘The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez’ in harrowing but essential docuseries

The name of Gabriel Fernandez still hangs heavy over the City of Los Angeles.

From the day the 8-year-old was found by Fire Department personnel on the floor of his Palmdale home after they responded to a 911 call from his mother, his story loomed large in the daily news. The paramedics had found Gabriel badly bruised and unresponsive, with profound injuries – broken ribs, a cracked skull, missing teeth, burnt skin, and BB bullets imbedded in his lungs and groin – that didn’t fit with the explanation they had been given for his condition. His mother, Pearl Sinthia Fernandez, and her boyfriend, Isauro Aguirre, claimed the boy had been injured by falling over a dresser and hitting his head. Gabriel was pronounced brain dead at the hospital on that same day, May 22, 2013; he was taken off life support and passed away two days later.

That tragic incident was the beginning of a seven-year ordeal for Gabriel’s family, his community, and the city itself. The child had been the victim of horrific and systematic abuse, perpetrated by his mother and Aguirre and allegedly motivated at least partly by Aguirre’s belief that the boy was gay; worse yet, other family members, as well as Gabriel’s teacher, had notified Children and Family Services multiple times over concerns that he was being mistreated, yet social workers had found, in every case but one, that their reports were unfounded – despite what seemed in retrospect to be clear indications to the contrary.

Fernandez and Aguirre were charged with first-degree murder in the death of Gabriel, with a special circumstance for torture, and in an unprecedented move, county prosecutors also charged four county social workers with one felony count each of child abuse and falsifying records.

The case dominated headlines as the ensuing investigation and court proceedings revealed ever more disturbing details about Gabriel’s short life and cruel death. The prosecution sought the death penalty for both of the perpetrators, who admitted to killing the child but claimed it had not been a pre-meditated act. Finally, in 2018, Aguirre was found guilty of the first degree changes and sentenced to death; Fernandez avoided the death penalty by agreeing to plead guilty.

In January of 2020, the charges against the four social workers were thrown out by a three-justice panel of the 2nd District Court of Appeal.

Now, Netflix is set to unveil “The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez,” a six-part docuseries which examines the case as it was laid out by LA County prosecutors, as well as chronicling journalistic efforts to track the weaknesses within the government agencies devoted to children’s welfare that permitted such a heartbreaking act to take place. Directed by documentarian Brian Knappenberger (“Nobody Speak: Trials of the Free Press”), it’s a gripping (and grim) deep dive into the case that may well be the most intense and upsetting true crime series the streaming network has produced so far.

Casting lead prosecutor Jon Hatami in the role of avenging hero, Knappenberger’s chronicle of the court case carefully avoids straying into sensationalism without shying away from the gruesome facts of Gabriel’s life. Through trial footage, interviews, and footage shot specifically for the show, we are given as comprehensive a look at the story as is possible in six hours of television, with the benefit and clarity of hindsight to assist in offering an overarching view of not only what happened, but of the systemic problems that led to a failure by those charged with protecting at-risk children to prevent the worst from happening to Gabriel. Perhaps most effectively, it repeatedly reminds us, through photos, footage, and the words of those who knew him, that Gabriel was a kind, loving, and gentle child who deserved much better treatment at the hands of those who should have been his caretakers.

As for the assertion that homophobia was a factor in Aguirre’s brutal beating and killing of his de-facto stepson, it doesn’t offer a lot of detail – prosecutors chose not to pursue a hate crime charge for strategic reasons, so that angle was only supplemental in proving a case for pre-meditation based solely on factual evidence – but it makes sure we hear about it in both through Hatami’s court statements and from the mouths of family members, who assert that Gabriel had been taken by the couple from his uncle and same-sex partner (previously given custody when his mother “didn’t want him” at birth) because they didn’t approve of a child being raised by gay parents. By all reports, Gabriel experienced the happiest and most supportive environment of his short life when he lived with them.

The Netflix series spends considerable time hammering home the shocking reality of the violence suffered by little Gabriel (described by Los Angeles Judge George G. Lomeli at Aguirre’s sentencing as “horrendous, inhumane and nothing short of evil”), and rightly so; to do anything less would be a disservice to his memory. Once it has done that, however, it sets its sights on the deeply shrouded county bureaucracy of Child and Family Services, the uniquely autonomous and powerful agency that oversees child welfare, and paints perhaps an even more disturbing picture of an organization overworked, understaffed, hamstrung by the financial priorities of privatization, and cloistered in a stubborn veil of secrecy that resisted not just inquiries from the press but from prosecutors as well. It also makes clear that law enforcement officials were well aware of the prior history of reported abuse in the Fernandez home before that fateful day when Gabriel’s life came to an end.

At the same time, Knappenberger takes care to offer a balanced view of the more complex ethical issues at the core of the case. His coverage of the four accused social workers, singled out in the minds of many as scapegoats by county officials looking for a means of damage control, is fair and compassionate, offering a glimpse at the daunting pressure and moral quandaries that face such civil servants; that it never quite lets them off the hook for the choices they made in handling Gabriel’s situation before it was too late is more testament to the journalistic integrity to which the series aspires.

Though the case of Gabriel Fernandez made the news nationwide, many outside of Los Angeles itself will likely only have passing familiarity with what happened. With “The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez,” Netflix is ensuring that Gabriel’s heartbreaking story will be known by millions – and while some may be hesitant to watch due to the disturbing nature of its conflict, it’s a show that demands to be seen. It reminds us, in no uncertain terms, that there are monsters in the world; but it also reminds us that for every Isauro Aguirre or Pearl Fernandez, there is also a Jon Hatami – someone who will stand up to fight for justice in the name of those who have suffered at their hands. Perhaps most important, it reminds us there is still much work to be done in perfecting the systems we have in place to serve our children – and that unrelenting, powerful journalism is still the best tool we have for holding those systems accountable.

“The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez” premieres on Wednesday, February 26, on Netflix. You can watch the trailer below.

Sports

Attitude! French ice dancers nail ‘Vogue’ routine

Cizeron and Fournier Beaudry strike a pose in memorable Olympics performance

Madonna’s presence is being felt at the Olympic Games in Italy.

Guillaume Cizeron and his rhythm ice dancing partner Laurence Fournier Beaudry of France performed a flawless skate to Madonna’s “Vogue” and “Rescue Me” on Monday.

The duo scored an impressive 90.18 for their effort, the best score of the night.

“We’ve been working hard the whole season to get over 90, so it was nice to see the score on the screen,” Fournier Beaudry told Olympics.com. “But first of all, just coming out off the ice, we were very happy about what we delivered and the pleasure we had out there. With the energy of the crowd, it was really amazing.”

Watch the routine on YouTube here.

Italy

Olympics Pride House ‘really important for the community’

Italy lags behind other European countries in terms of LGBTQ rights

The four Italian advocacy groups behind the Milan Cortina Winter Olympics’ Pride House hope to use the games to highlight the lack of LGBTQ rights in their country.

Arcigay, CIG Arcigay Milano, Milano Pride, and Pride Sport Milano organized the Pride House that is located in Milan’s MEET Digital Culture Center. The Washington Blade on Feb. 5 interviewed Pride House Project Manager Joseph Naklé.

Naklé in 2020 founded Peacox Basket Milano, Italy’s only LGBTQ basketball team. He also carried the Olympic torch through Milan shortly before he spoke with the Blade. (“Heated Rivalry” stars Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie last month participated in the torch relay in Feltre, a town in Italy’s Veneto region.)

Naklé said the promotion of LGBTQ rights in Italy is “actually our main objective.”

ILGA-Europe in its Rainbow Map 2025 notes same-sex couples lack full marriage rights in Italy, and the country’s hate crimes law does not include sexual orientation or gender identity. Italy does ban discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment, but the country’s nondiscrimination laws do not include gender identity.

ILGA-Europe has made the following recommendations “in order to improve the legal and policy situation of LGBTI people in Italy.”

• Marriage equality for same-sex couples

• Depathologization of trans identities

• Automatic co-parent recognition available for all couples

“We are not really known to be the most openly LGBT-friendly country,” Naklé told the Blade. “That’s why it (Pride House) was really important for the community.”

“We want to use the Olympic games — because there is a big media attention — and we want to use this media attention to raise the voice,” he added.

Naklé noted Pride House will host “talks and roundtables every night” during the games that will focus on a variety of topics that include transgender and nonbinary people in sports and AI. Another will focus on what Naklé described to the Blade as “the importance of political movements now to fight for our rights, especially in places such as Italy or the U.S. where we are going backwards, and not forwards.”

Seven LGBTQ Olympians — Italian swimmer Alex Di Giorgio, Canadian ice dancers Paul Poirier and Kaitlyn Weaver, Canadian figure skater Eric Radford, Spanish figure skater Javier Raya, Scottish ice dancer Lewis Gibson, and Irish field hockey and cricket player Nikki Symmons — are scheduled to participate in Pride House’s Out and Proud event on Feb. 14.

Pride House Los Angeles – West Hollywood representatives are expected to speak at Pride House on Feb. 21.

The event will include a screening of Mariano Furlani’s documentary about Pride House and LGBTQ inclusion in sports. The MiX International LGBTQ+ Film and Queer Culture Festival will screen later this year in Milan. Pride House Los Angeles – West Hollywood is also planning to show the film during the 2028 Summer Olympics.

Naklé also noted Pride House has launched an initiative that allows LGBTQ sports teams to partner with teams whose members are either migrants from African and Islamic countries or people with disabilities.

“The objective is to show that sports is the bridge between these communities,” he said.

Bisexual US skier wins gold

Naklé spoke with the Blade a day before the games opened. The Milan Cortina Winter Olympics will close on Feb. 22.

More than 40 openly LGBTQ athletes are competing in the games.

Breezy Johnson, an American alpine skier who identifies as bisexual, on Sunday won a gold medal in the women’s downhill. Amber Glenn, who identifies as bisexual and pansexual, on the same day helped the U.S. win a gold medal in team figure skating.

Glenn said she received threats on social media after she told reporters during a pre-Olympics press conference that LGBTQ Americans are having a “hard time” with the Trump-Vance administration in the White House. The Associated Press notes Glenn wore a Pride pin on her jacket during Sunday’s medal ceremony.

“I was disappointed because I’ve never had so many people wish me harm before, just for being me and speaking about being decent — human rights and decency,” said Glenn, according to the AP. “So that was really disappointing, and I do think it kind of lowered that excitement for this.”

Puerto Rico

Bad Bunny shares Super Bowl stage with Ricky Martin, Lady Gaga

Puerto Rican activist celebrates half time show

Bad Bunny on Sunday shared the stage with Ricky Martin and Lady Gaga at the Super Bowl halftime show in Santa Clara, Calif.

Martin came out as gay in 2010. Gaga, who headlined the 2017 Super Bowl halftime show, is bisexual. Bad Bunny has championed LGBTQ rights in his native Puerto Rico and elsewhere.

“Not only was a sophisticated political statement, but it was a celebration of who we are as Puerto Ricans,” Pedro Julio Serrano, president of the LGBTQ+ Federation of Puerto Rico, told the Washington Blade on Monday. “That includes us as LGBTQ+ people by including a ground-breaking superstar and legend, Ricky Martin singing an anti-colonial anthem and showcasing Young Miko, an up-and-coming star at La Casita. And, of course, having queer icon Lady Gaga sing salsa was the cherry on the top.”

La Casita is a house that Bad Bunny included in his residency in San Juan, the Puerto Rican capital, last year. He recreated it during the halftime show.

“His performance brought us together as Puerto Ricans, as Latin Americans, as Americans (from the Americas) and as human beings,” said Serrano. “He embraced his own words by showcasing, through his performance, that the ‘only thing more powerful than hate is love.’”

-

Colombia5 days ago

Colombia5 days agoLGBTQ Venezuelans in Colombia uncertain about homeland’s future

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoBlade, Pride House LA announce 2028 Olympics partnership

-

Calendar5 days ago

Calendar5 days agoCalendar: February 6-12

-

District of Columbia5 days ago

District of Columbia5 days agoD.C. non-profits find creative ways to aid the unhoused amid funding cuts