homepage news

amfAR’s Dr. Mathilde Krim dead at 91

AIDS pioneer’s life reflects LGBT/AIDS history

Dr. Mathilda Krim (Washington Blade file photo by Doug Hinckle)

Dr. Mathilde Krim, a wealthy, straight, scientific researcher who devoted her life to fighting HIV/AIDS, died on Monday (Jan. 15, 2018) at her home in Kings Point, N.Y. at the age of 91.

“The board of trustees and staff of amfAR mourn the passing of our beloved Founding Chairman, Mathilde Krim, Ph.D. A pioneer in AIDS research and activism, Dr. Krim was at the forefront of scientific and philanthropic responses to HIV/AIDS long before the world fully understood its catastrophic global reach,” reads amfAR’s statement issued Tuesday morning.

“As amfAR’s founding chairman, and chairman of the board from 1990 to 2004, she was the heart and soul of the organization. She helped create it, supported it, kept it afloat more than once, and guided it with extraordinary dedication. She testified on Capitol Hill on several occasions, and was a driving force behind legislation that expanded access to lifesaving treatment and behind efforts to scale up federal funding for AIDS research. In August 2000, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom – the highest civilian honor in the United States,” the statement continued.

“Dr. Krim had such a profound impact on the lives of so many. While we all feel a penetrating sadness at the loss of someone we loved so deeply, it is important to remember how much she gave us and the millions for whom she dedicated her life. There is joy to be found in knowing that so many people alive today literally owe their lives to this great woman,” amfAR concluded.

New York-based Gay USA co-host and co-producer Andy Humm and longtime AIDS activist Peter Staley were the first to note Krim’s passing on their Facebook pages Monday night.

“My greatest AIDS hero died a few hours ago,” Staley wrote. “Dr. Mathilde Krim, founder of amfAR, warrior against homophobia and AIDS-related stigma, dedicated defender of science and public health, and mother-figure and mentor to countless activists, will leave a deep hole in the continued fight against AIDS — a fight she dedicated her life to. She was 91.”

“All honor to the great Dr. Mathilde Krim, founder of AmFAR (started as the AIDS Medical Foundation in 1983), who died today at 91–a giant in the fight against HIV and AIDS bringing both scientific and fundraising savvy and celebrities to the cause in the worst years of the AIDS pandemic. A tireless brilliant, calm, steady voice for healing, research, compassion and justice. Millions owe her their lives,” Humm wrote.

Krim’s passion to help people with AIDS was fueled by seeing newsreel footage as a teenager of the Nazi Holocaust during World War II. “What it did was to sensitize me against injustice. It’s really basically that—cruelty and injustice. And it’s a theme in my life,” Krim said in a 1990 interview.

”I volunteered for the [AIDS Medical Foundation] because I was incensed!” Krim said in a Nov. 1984 interview with the New York Times in her interferon laboratory at Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, promoting the foundation’s first fundraiser—dinner and a fashion show headlined as Fashion Affair ’84. ”So many young men were dying, mostly intelligent and sophisticated young men, some of the city’s best products. And many would be dying abandoned or alone because they were afraid to contact their families.”

Krim’s life reads like a movie script with multiple odd juxtapositions—fashion, science, young gay men dying of AIDS while also being a “traditional wife” of a Hollywood studio head.

Krim was born Mathilde Galland in Cuomo, Italy in 1926. Her Swiss father was an agronomist and her mother, who was of Austrian descent, had grown up in Czechoslovakia. Her father moved the family to Geneva, Switzerland when she was 6.

As World War II started to break out in Europe, Krim heard stories about “sinister-sounding people called the Jews.”

At one point one summer, Krim worked as a gopher in the office of a lawyer who represented the United Jewish Appeal in Geneva. She saw the influx of Jewish refugees seeking asylum in Switzerland, only to be scoffed at and turned over to the Nazi-aligned Vichy French if they had no bank accounts.

“It made me sick. I was 16, 17, you know; one is impressionable. I was indignant. I decided, ‘Oh, no, I`m not going to live in a country that does this,’” she told an interviewer in 1990.

The epiphany came one day when she saw newsreel footage about the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps. “I went home and cried and told my parents. They said, ‘Oh, it may be exaggerated; it may not all be true.’ I kept crying; I was in a state of shock. And that lasted several days. To be young and to be unprepared for something like that-it was a terrible psychological shock,” Krim said. “I had never ever seen somebody die or dead, you know, and there I see human bones-most horrible pictures-being dumped from a truck into a hole in the ground, and this kind of thing.”

”I grew up not really knowing what was going on in the camps,” Krim said in 1988, ”though I knew that there was a good deal of anti-Semitism in Europe. My parents were no worse than the others, but they were like the others.”

But the “idea that people of my society were responsible for what had happened—it was very shocking to me. And I became very interested in knowing who were those Jews whom everybody had been after. Because I heard those terrible stories, that they were exploiting others, and I wanted to see for myself.”

In 1945, Krim went to the University of Geneva and met Jews from British-controlled Palestine. ”They were totally different from what I was told,” she said. ”I thought, ‘My God, if anything, I want to be like them.’ ”

Mathilde converted to Judaism and started working with a militant anti-British underground movement called the Irgun, run by a radical Zionist named Menachem Begin. Mathilde helped smuggle weapons to Begin from old French Resistance sympathizers. (When Begin became Israeli prime minister years later, he would be Krim’s houseguest.)

During this time, Krim studied biology in Geneva and, in 1953, received her Ph.D. She also fell in love with fellow Jewish radical David Danon and took his medical courses when he was away. The couple married and moved to Israel in early 1953. “We were in perfect harmony as long as the world was against us. But as soon as the pressure was off, we divorced,” she said.

Dr. Mathilde Krim (Photo courtesy amfAR)

Krim became a junior researcher at the Weizmann Institute of Science and in 1956 was asked to give a tour to a honcho on the institute’s board of directors—New York movie executive Arthur Krim. They married in 1958 and moved to New York. Krim’s 7-year old daughter Daphna adjusted better than her mother. But eventually, Krim found a job at Cornell University Medical School where she studied virology, with the added benefit of being able to speak German, French, Italian, English, Hebrew and ”some Spanish.”

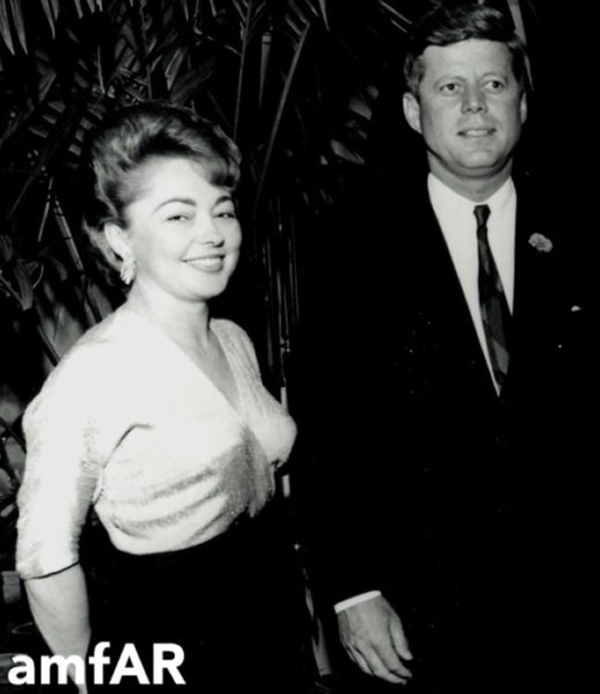

In 1962, Krim transferred to Sloan Kettering to pursue research into whether cancer might be caused by viruses. Her lawyer husband Arthur Krim, meanwhile, became chair of Orion Pictures and a prominent Democratic fundraiser and senior advisor to three Presidents—John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson and Jimmy Carter. Mathilde Krim was the gracious hostess in their art-filled townhouse on East 69th Street when a president or presidential contenders such as Walter Mondale held court or stayed over.

Her husband was also a big fan of Democrat intellectual Adlai Stevenson, which spurred the couple’s interest in the civil rights movement in the US and Africa. With her passion to fight injustice, Krim became a member of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and in 1966, joined the National Urban League. Meanwhile, from 1966 to 1968, Arthur Krim served as chair of the Democratic National Finance Committee.

By 1970, while writing a research report for a panel studying the history of cancer—a report that played a significant role in passage the National Cancer Act of 1971—Krim discovered an account of interferon, “a naturally occurring protein that seemed to ‘interfere’ with viruses, including those that caused tumors. Some experiments even indicated that interferon was effective against the tumors themselves,” according to the New York Times.

Krim was hooked on the possibility that interferon could lead to a more humane biological treatment for cancer, though other researchers were considerably less impressed, calling it ”imaginon,” accusing her of letting her heart rule her head. She was soon dubbed the Interferon Queen—a nicknamed she earned, using guile to get funding from the National Cancer Institute after being turned down. In 1975, she convinced the institute to sponsor an international conference on interferon and the night before she and her Hollywood-connected husband threw a party for 100 at their swank Manhattan townhouse.

”She more or less singlehandedly rescued the field from oblivion,” Martin S. Hirsch, an interferon expert at Massachusetts General Hospital, told the New York Times.

Dr. Mathilde Krim with President John F. Kennedy (Photo courtesy amfAR)

The institute gave her funding, as did the American Cancer Society, and by 1981, Krim had $6 million for her research, in addition to what she could raise from outside foundations and donors. Though touted as a possible cancer breakthrough, the research initially yielded mostly disappointments, treating only a rare form of leukemia. Her reputation as a detached scientist was questioned.

‘I probably could have done more if I had a husband less involved in things,” Krim told The New York Times in 1984. “Research is such a competitive life, and most of my colleagues are men who have wives who do everything at home. I know if I have to give a dinner for 100 people and be all dressed up and have my hair done, I can’t concentrate completely on my work.”

But in 1980, Krim’s attention was diverted by mysterious symptoms impacting patients of her research colleague, Dr. Joseph Sonnabend, who practiced medicine in Greenwich Village. Gay men were coming to him with enlarged lymph nodes, enlarged spleens and infections that failed to respond to treatment—and they had seriously compromised immune systems.

“Clearly, it was a biological infectious agent that was causing this disease and we also concluded that it must be sexually transmissible. My friend started using his medical practice as a source of clinical (blood) samples; he would send them around to experts to try to find another link, but nobody would figure out anything,” Krim later recalled. “In the spring of `81 Dr. Sonnabend came to tell us that some of his patients were dying, and our research activities were intensified.”

By then, Krim was the director of the interferon laboratory at Sloan-Kettering. “It was totally mind-blowing for a scientist who thinks she knows something to realize that, here in the middle of New York in the 20th century, a new disease could occur,” Krim said. “I personally didn’t believe for a minute that being gay could cause it. It was a scientific and medical puzzle that attracted my attention.”

Krim and Sonnabend worried that the mysterious disease was spreading but no one seemed to listen. The disease was killing those who “deserved it.”

Though her husband had gay friends, Krim told POZ Magazine, “I knew nothing about the gay community in 1981. Dr. Joseph Sonnabend sent me his patients, including Michael Callen, who told me what gay life was. That was quite an education! I was disgusted by the way society accused gay men of having created something terrible. When you think of it, the promiscuous life was caused by society—it didn’t allow gay men to get married or to have honest relationships. They had to hide.”

Krim’s compassion and hatred of injustice set in.

“In those early days, they were literally dying in the streets,” Krim told the Los Angeles Times in 2000. “[Gay men who had AIDS] lost their jobs, their apartments–their families turned away from them. It turned my stomach, it really impacted me and I decided this was something not to be tolerated.”

Unable to raise funding for their research, the colleagues decided to start their own organization in June 1983. The AIDS Medical Foundation (AMF) was co-founded by Krim—then 57 years old—Sonnabend, Nobel-prize winning scientist Dr. David Baltimore, singer, Sonnabend patient and AIDS activist Michael Callen (co-founder with fellow Sonnabend patient Richard Berkowitz of the People with AIDS Coalition), and respected philanthropist Mary Lasker.

The foundation was created to serve as a “scientific venture capitalist” to give provide seed money to researchers and scientists with promising AIDS-related projects that had been turned down for government grants. They wanted to be the AIDS version of the American Cancer Society. Arthur Krim kicked in the first $100,000 and within 90 days, Mathilde Krim had raised an additional $550,000. She also continued her interferon research, oversaw AMF operations, visited hospitals and clinics, and hosted fundraisers. Nothing was easy with efforts hampered by stigma. The AIDS Medical Foundation could not even list its full name in the lobby index in the Helmsley Building at 230 Park Avenue, having to list its office as A.M. Foundation.

Working together wasn’t easy, either. When Callen and Berkowitz wrote the first risk-reduction pamphlet under Sonnabend’s oversight entitled “How to Have Sex in an Epidenic: One Approach” espousing condom use, they approached Krim about publishing the safe sex guide through AMF. However, POZ founder Sean Strub writes in his book Body Counts, “Krim balked, fearing the frank language about anal sex was too risqué and would turn off potential donors. She did agree to let the foundation serve as a fiscal pass-through, so donations to print it would be tax-deductible.”

It was a serious concern, with donors from large corporations and Wall Street investment houses buying into the mythology of homosexuality.

”They felt that this was a disease that resulted from a sleazy life style, drugs or kinky sex—that certain people had learned their lesson and it served them right,” Krim told the New York Times in 1988.

”That was the attitude, even on the part of respectable foundations that are supposed to be concerned about human welfare.”

It sounded like the anti-Semitic propaganda she heard about Jews from the Nazis and Nazi sympathizers. ”I thought we had to enlarge our board and diversify—load it with straight people so that it’s not one more gay organization,” she said. To that end, she brought on board Elizabeth Kummerfeld, whose husband, Donald D. Kummerfeld, was president of Magazine Publishers of America. They set about planning for a $150-a-ticket November 1984 fashion show at the Tower Gallery, 45 West 18th Street, for which 50 designers, including Pauline Trigere, Bill Blass, Zandra Rhodes, Adolfo Galanos and Calvin Klein, and other designers agreed to donate dresses and gowns. The show as narrated by Arlene Francis, followed by an auction and a buffet planned by Craig Claiborne. Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, a friend of the Krims, attended.

Funding for Sonnabend’s research and perhaps a clinic was imperative. “We need such a clinic,” Krim told the New York Times in 1984, ”because it’s a place where patients can come without fear of discrimination. We deal with a population afraid of discriminatory practices, and that is not only gay men but drug users as well.”

The AIDS situation as ”very worrisome,” she continued. ”It’s not going to remain in the high- risk groups. All the evidence shows the disease is spreading in all directions, but people just aren’t worried anymore.”

At the same time, on the other side of the country in Los Angeles, pioneering AIDS researcher and immunologist Dr. Michael Gottlieb, was working with actress Elizabeth Taylor to create a foundation using $250,000 in start-up funding contributed by the late actor Rock Hudson, close friend of Taylor’s and a patient of Gottlieb’s. Krim called them about joining their efforts in the summer of 1985.

“Elizabeth Taylor and others were forming a like-minded organization on the West Coast, and I went out to visit her. She invited me to her house, and was immediately interested in working together, so we joined our organizations to form the American Foundation for AIDS Research,” Krim said in a 2015 interview. “From then on, Elizabeth dedicated herself to doing public speaking and even testifying in front of Congress.”

‘It was a shotgun marriage,” Gottlieb told Vanity Fair in 1992, a marriage of necessity between science and show business.

“It did occur to me that having AmFAR on the East and West coasts might dilute it,” Taylor said. “Then I realized that Mathilde is a very powerful lady with a background that couldn’t have been more suitable. So it seemed like a very large and powerful decision.”

(Photo courtesy amfAR)

Mathilde Krim is “a smart woman and one of the most powerful I’ve ever met,” says Bill Misenhimer, who became amFAR’s first executive director, told the magazine. “You don’t fight her because she always wins. And AIDS is her life.”

“We complement each other very well,” Krim told VF, shrugging off questions about clashes. “I have a professional education in biology and medicine, and because I’m not a public figure I can work at the desk long hours. I mind the shop. Elizabeth contributes to projecting an image of the organization. She deals with the public very well.”

That was a quick lesson learned for the new national organization when Taylor appeared at the second amFAR fashion show in 1985 in Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in New York City. “We’d dutifully set in place security protection, but we didn’t make sufficient arrangements,” Krim recalled. “We didn’t realize she’d be mobbed by the crowd. She was atop a staircase with all the paparazzi and the public pushing behind—they almost threw her down.”

While Krim was gaining momentum with AMF, she was being unfavorably scrutinized at Sloan-Kettering by new president Paul A. Marks.

”I was told very clearly that I should tone down my visibility,” Krim told the NYT in 1988. ”He didn’t want his institute to become known as an AIDS hospital. Bad blood developed and at one point I decided, ‘This is enough.’”

(A spokesperson told the NYT that Sloan-Kettering continued to contribute to research on AIDS and interferon therapy.)

Krim left Sloan-Kettering in 1985 and subsequently became an associate research scientist at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt. But she was finished as a research scientist. In 2000, the Los Angeles Times noted that her besmirched, dogged research into interferon were vindicated: “Interferon has proved effective in inducing remissions in hairy-cell leukemia, and now is used to treat a long list of serious maladies: bladder cancer, renal cell cancer, hepatitis C, malignant melanoma, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma.”

Serving as AmFAR’s board chair suited her. ”I came to the conclusion that it’s better if I stay on the outside and help people inside the labs,” she said. ”I’m not such a genius that somebody else cannot do what I was doing. And these would be people who cannot do what I can.”

But Krim was able to use that scientific knowledge to challenge important issues that others took as fact. One of the most critical examples was in 1986—before ACT UP—when she took on the medical establishment over the testing of AZT. Per protocol, half the test subjects were given placebos, which Krim concluded would mean the placebo group could possible die by the time the effectiveness of the drug was determined. Though not a cure and saddled with harmful side effects, at least AZT could extend the dying person’s life for a few months.

”People who are on their last legs should get anything they want,” she said. ”We should just make sure we’re not killing them with it.”

Dr. Mathilde Krim (Photo courtesy amfAR)

Krim testfied before Congress that she opposed placebos in “double-blind” drug trials for people with full-blown AIDS. She lost out to two powerful opponents—National Cancer Institute top AIDS drug expert Samuel Broder and NIH AIDS research coordinator Anthony S. Fauci. But she eventually helped convince the NIH two years later to stop using placebos and to use AZT as the control instead. Additionally, Broder joined AmFAR’s scientific advisory committee, helping determine who gets grants.

One of amFAR’s biggest nights was the appearance of President Ronald Reagan, who had been invited by Taylor to speak at the benefit where Surgeon General Koop was among the honorees. It was Reagan’s second term in office and he had not yet addressed the AIDS epidemic. The benefit was the night before the third international conference on AIDS in Washington.

”He and his advisers must have thought that this was a good opportunity to appear in public in front of people who would behave reasonably well,” Krim told the New York Times in 1988.

A Presidential speechwriter talked to AmFAR’s president Mervyn F. Silverman, who suggested that Reagan stress compassion and avoid the controversial systematic testing for the AIDS virus.

”The President said some of the right things, but he chose to mention testing,” Krim said. ”So that was the undoing of the rest of his speech. Even in our audience some people resented it, and he was in fact hissed, which was not the polite thing to do. But he should have known better.”

In fact, that May 31, 1987 speech contained harsh words reflective of his religious right domestic policy base. As of April 1987, the Centers for Disease Control reported 33,997 cases of AIDS in the US, with 19,658 deaths, no cure and the pall of stigma hanging over the country.

“If a person has reason to believe that he or she may be a carrier, that person has a moral duty to be tested for AIDS; human decency requires it. And the reason is very simple: Innocent people are being infected by this virus, and some of them are going to acquire AIDS and die,” Reagan said. “I’ve asked the Department of Health and Human Services to determine as soon as possible the extent to which the AIDS virus has penetrated our society and to predict its future dimensions.”

He said the AIDS immigration ban, testing for all federal prisoners, and possibly testing of veterans, “in addition to the testing already underway in our military and foreign service.”

“[Reagan’s speechwriters] didn’t know anything about AIDS, so we wrote the first half of the speech, where Reagan talked about compassion, justice, care — all the right things,” Krim told Vanity Fair. “We asked them to please not talk about mandatory testing, because it was not recommended scientifically, legally, or medically. We said it would elicit a furious reaction from the public. But one of Reagan’s advisers revised the speech and put it in.”

“The president mentioned mandatory testing and people jumped out of their seats. Then they started heckling him, so I jumped up and said, ‘Don’t be rude. This is your president and he is our guest,’” Taylor told the magazine.

Krim stuck with amFar until 2005 when she stepped down as founding chair, having helped build the organization into a prominent private supporter of AIDS research. Michael Musto wrote in POZ magazine, “As Dr. Mathilde Krim ‘a.k.a. the Mother of AIDS advocacy’ passes the amfAR torch to classy designer Kenneth Cole, her once-great institution may claim it’s not losing a legend but gaining a brand name. But can its new leader see past the bottom line to make amfAR not only fashionable but relevant again?”

amfAR would argue they are exceedingly relevant with their latest grants to three young scientists working on new HIV treatments and “leveraging vaccine research to help cure HIV.”

Krim does not leave this earth a saint—she disagreed with Taylor about going international, for instance, a debate Taylor won with the organization being renamed the Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR, versus amFAR). To date amfAR has raised and invested an estimated $517 million for thousands of programs, according to the New York Times obituary on Krim.

And Taylor was not the only one with whom Krim disagreed, especially over political issues. In 1990, New York Mayor David N. Dinkins asked Krim about naming a city health commissioner. Krim recommended Indiana’s commissioner, Dr. Woodrow A. Myers Jr., who advocated names-reporting and possible quarantining of people with AIDS. Krim and others thought about it, stepped back, then re-endorsed Myers, then withdrew the endorsement. Myers was eventually appointed anyway and Krim was out in the cold.

“I think she’s exceptionally naïve politically,” playwright Larry Kramer told The Times. “We are all very angry with her, so far as one can ever get angry with Mathilde, because we love her so.”

But in 2000, Krim received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Clinton for her decades of AIDS-related work. And the National Portrait Gallery accepted two photographic portraits of Krim into its permanent collection in recognition of her leadership in the fight against HIV/AIDS—portraits by leading American photographers Annie Leibovitz and Joyce Tenneson.

Dr. Mathilde Krim receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bill Clinton (Photo courtesy amfAR)

”Everybody thinks of at least one person whom he has lost or is afraid for,” Krim told the New York Times in 1988. ”And I am no different. I have my little list.”

And now it’s Mathilde Krim who is on the list of AIDS heroes who have died.

“Dr. Krim was a close friend and mentor, and I am deeply saddened by this news. She dedicated her life to understanding the science behind the epidemic, and was a force to mobilize research around the globe that helped to save millions of lives and reduce the stigma attached to HIV/AIDS,” Elton John, Founder of the Elton John AIDS Foundation (EJAF). “The legacy of Dr. Krim’s deep commitment to ending HIV/AIDS will live on in the advocacy, action, and compassion of those that follow her lead. We would not be where we are today without her, and we must continue to work tirelessly to further understand and prevent the disease. My thoughts are with her family at this time, she was a true hero.”

“For over three decades, I have witnessed one of the most remarkable women in my lifetime fight against the plague of HIV/AIDS,” longtime LGBT rights activist/author David Mixner, who was honored by amfAR. “Dr. Krim was there when no one else would even touch us. There was not one day in the fight against this epidemic that she wasn’t working by our side. Dr. Mathilde Krim was a true legend, heroine and a dear friend.”

“We have lost an inspirational, tireless, and catalytic leader of our movement,” said Mark Harrington, Treatment Action Group’s Executive Director. “Dr. Krim understood the gravity of the epidemic, in its earliest and darkest days, and was driven by her own remarkable intelligence, fierce commitment to civil rights and social justice, extraordinary social and political networks, and true grit to galvanize funders, scientists, policy leaders, and activists toward a single cause: ending HIV and AIDS as a threat to humanity.”

“I genuinely believe that we wouldn’t be where we are today without Dr. Krim’s brilliance, determination, and mobilization,” said Tim Horn, Deputy Executive Director of HIV & HCV Programs at TAG. “Beyond her unparalleled contributions to HIV/AIDS research fundraising and awareness, she was an interminable source of strength, support, and wisdom for countless activists over the years.”

“TAG has lost a matriarch of our family, a leader in our movement, and a steadfast supporter of our work,” said Barbara Hughes, President of TAG’s Board of Directors. “We mourn Dr. Krim’s passing and join amfAR and so many leaders in the fight against HIV/AIDS in remembering her work and life.”

“Matilda Krim was a pioneering legend. Her compassion and foresight at the very beginning of the epidemic played a crucial role in mobilizing support to fight the battle against AIDS,” says Michael Weinstein, president of AIDS Healthcare Foundation.

“Even though Mathilde has been gone for a while from any active Public role, it does feel like the end of an era,” says Sean Strub, founder of POZ Magazine and out HIV-positive mayor of Milford, Pennsylvania.

“Mathilde used her resources, curiosity, tenacity and heart to provide leadership and build support to fund AIDS research at a time when few of her peers were willing to do so. The history of the epidemic is intertwined with her own; she was persistent, unflappable and prescient.”

“I became aware of Mathilde Krim around 1988, while I was working as the staff writer for the National AIDS Network, a coalition of community-based AIDS service organizations in Washington, D.C. By then Dr. Krim was already legendary in the HIV-AIDS community,” says John-Manuel Andriote, author of Victory Deferred: How AIDS Changed Gay Life in America. “It’s hard to overstate the importance of Dr. Krim and Elizabeth Taylor’s “mainstream” (and heterosexual) cachet in helping to ratchet down the fear and stigma associated with what then was a deadly new illness perceived as mainly afflicting gay men.”

“As an HIV positive man who has been living with the virus for over 13 years, I know that I would not be alive today without the efforts of Dr. Mathilde Krim,” says out New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson. “I met her during my first trip to New York City, at age 18. Little did I know the important role she would play in my life. My thoughts and prayers go to the family and friends of Dr. Krim. Her legacy will live on in the countless lives she saved.”

homepage news

Honoring the legacy of New Orleans’ 1973 UpStairs Lounge fire

Why the arson attack that killed 32 gay men still resonates 50 years later

On June 23 of last year, I held the microphone as a gay man in the New Orleans City Council Chamber and related a lost piece of queer history to the seven council members. I told this story to disabuse all New Orleanians of the notion that silence and accommodation, in the face of institutional and official failures, are a path to healing.

The story I related to them began on a typical Sunday night at a second-story bar on the fringe of New Orleans’ French Quarter in 1973, where working-class men would gather around a white baby grand piano and belt out the lyrics to a song that was the anthem of their hidden community, “United We Stand” by the Brotherhood of Man.

“United we stand,” the men would sing together, “divided we fall” — the words epitomizing the ethos of their beloved UpStairs Lounge bar, an egalitarian free space that served as a forerunner to today’s queer safe havens.

Around that piano in the 1970s Deep South, gays and lesbians, white and Black queens, Christians and non-Christians, and even early gender minorities could cast aside the racism, sexism, and homophobia of the times to find acceptance and companionship for a moment.

For regulars, the UpStairs Lounge was a miracle, a small pocket of acceptance in a broader world where their very identities were illegal.

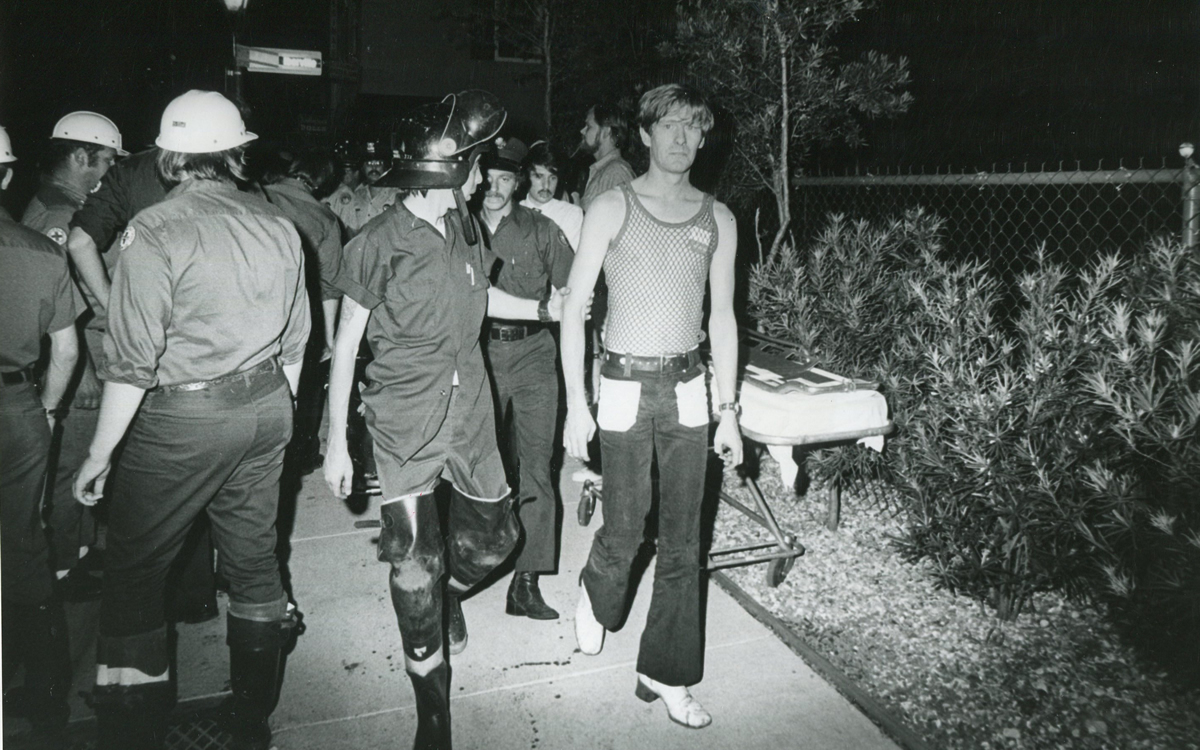

On the Sunday night of June 24, 1973, their voices were silenced in a murderous act of arson that claimed 32 lives and still stands as the deadliest fire in New Orleans history — and the worst mass killing of gays in 20th century America.

As 13 fire companies struggled to douse the inferno, police refused to question the chief suspect, even though gay witnesses identified and brought the soot-covered man to officers idly standing by. This suspect, an internally conflicted gay-for-pay sex worker named Rodger Dale Nunez, had been ejected from the UpStairs Lounge screaming the word “burn” minutes before, but New Orleans police rebuffed the testimony of fire survivors on the street and allowed Nunez to disappear.

As the fire raged, police denigrated the deceased to reporters on the street: “Some thieves hung out there, and you know this was a queer bar.”

For days afterward, the carnage met with official silence. With no local gay political leaders willing to step forward, national Gay Liberation-era figures like Rev. Troy Perry of the Metropolitan Community Church flew in to “help our bereaved brothers and sisters” — and shatter officialdom’s code of silence.

Perry broke local taboos by holding a press conference as an openly gay man. “It’s high time that you people, in New Orleans, Louisiana, got the message and joined the rest of the Union,” Perry said.

Two days later, on June 26, 1973, as families hesitated to step forward to identify their kin in the morgue, UpStairs Lounge owner Phil Esteve stood in his badly charred bar, the air still foul with death. He rebuffed attempts by Perry to turn the fire into a call for visibility and progress for homosexuals.

“This fire had very little to do with the gay movement or with anything gay,” Esteve told a reporter from The Philadelphia Inquirer. “I do not want my bar or this tragedy to be used to further any of their causes.”

Conspicuously, no photos of Esteve appeared in coverage of the UpStairs Lounge fire or its aftermath — and the bar owner also remained silent as he witnessed police looting the ashes of his business.

“Phil said the cash register, juke box, cigarette machine and some wallets had money removed,” recounted Esteve’s friend Bob McAnear, a former U.S. Customs officer. “Phil wouldn’t report it because, if he did, police would never allow him to operate a bar in New Orleans again.”

The next day, gay bar owners, incensed at declining gay bar traffic amid an atmosphere of anxiety, confronted Perry at a clandestine meeting. “How dare you hold your damn news conferences!” one business owner shouted.

Ignoring calls for gay self-censorship, Perry held a 250-person memorial for the fire victims the following Sunday, July 1, culminating in mourners defiantly marching out the front door of a French Quarter church into waiting news cameras. “Reverend Troy Perry awoke several sleeping giants, me being one of them,” recalled Charlene Schneider, a lesbian activist who walked out of that front door with Perry.

Esteve doubted the UpStairs Lounge story’s capacity to rouse gay political fervor. As the coroner buried four of his former patrons anonymously on the edge of town, Esteve quietly collected at least $25,000 in fire insurance proceeds. Less than a year later, he used the money to open another gay bar called the Post Office, where patrons of the UpStairs Lounge — some with visible burn scars — gathered but were discouraged from singing “United We Stand.”

New Orleans cops neglected to question the chief arson suspect and closed the investigation without answers in late August 1973. Gay elites in the city’s power structure began gaslighting the mourners who marched with Perry into the news cameras, casting suspicion on their memories and re-characterizing their moment of liberation as a stunt.

When a local gay journalist asked in April 1977, “Where are the gay activists in New Orleans?,” Esteve responded that there were none, because none were needed. “We don’t feel we’re discriminated against,” Esteve said. “New Orleans gays are different from gays anywhere else… Perhaps there is some correlation between the amount of gay activism in other cities and the degree of police harassment.”

An attitude of nihilism and disavowal descended upon the memory of the UpStairs Lounge victims, goaded by Esteve and fellow gay entrepreneurs who earned their keep via gay patrons drowning their sorrows each night instead of protesting the injustices that kept them drinking.

Into the 1980s, the story of the UpStairs Lounge all but vanished from conversation — with the exception of a few sanctuaries for gay political debate such as the local lesbian bar Charlene’s, run by the activist Charlene Schneider.

By 1988, the 15th anniversary of the fire, the UpStairs Lounge narrative comprised little more than a call for better fire codes and indoor sprinklers. UpStairs Lounge survivor Stewart Butler summed it up: “A tragedy that, as far as I know, no good came of.”

Finally, in 1991, at Stewart Butler and Charlene Schneider’s nudging, the UpStairs Lounge story became aligned with the crusade of liberated gays and lesbians seeking equal rights in Louisiana. The halls of power responded with intermittent progress. The New Orleans City Council, horrified by the story but not yet ready to take its look in the mirror, enacted an anti-discrimination ordinance protecting gays and lesbians in housing, employment, and public accommodations that Dec. 12 — more than 18 years after the fire.

“I believe the fire was the catalyst for the anger to bring us all to the table,” Schneider told The Times-Picayune, a tacit rebuke to Esteve’s strategy of silent accommodation. Even Esteve seemed to change his stance with time, granting a full interview with the first UpStairs Lounge scholar Johnny Townsend sometime around 1989.

Most of the figures in this historic tale are now deceased. What’s left is an enduring story that refused to go gently. The story now echoes around the world — a musical about the UpStairs Lounge fire recently played in Tokyo, translating the gay underworld of the 1973 French Quarter for Japanese audiences.

When I finished my presentation to the City Council last June, I looked up to see the seven council members in tears. Unanimously, they approved a resolution acknowledging the historic failures of city leaders in the wake of the UpStairs Lounge fire.

Council members personally apologized to UpStairs Lounge families and survivors seated in the chamber in a symbolic act that, though it could not bring back those who died, still mattered greatly to those whose pain had been denied, leaving them to grieve alone. At long last, official silence and indifference gave way to heartfelt words of healing.

The way Americans remember the past is an active, ongoing process. Our collective memory is malleable, but it matters because it speaks volumes about our maturity as a people, how we acknowledge the past’s influence in our lives, and how it shapes the examples we set for our youth. Do we grapple with difficult truths, or do we duck accountability by defaulting to nostalgia and bluster? Or worse, do we simply ignore the past until it fades into a black hole of ignorance and indifference?

I believe that a factual retelling of the UpStairs Lounge tragedy — and how, 50 years onward, it became known internationally — resonates beyond our current divides. It reminds queer and non-queer Americans that ignoring the past holds back the present, and that silence is no cure for what ails a participatory nation.

Silence isolates. Silence gaslights and shrouds. It preserves the power structures that scapegoat the disempowered.

Solidarity, on the other hand, unites. Solidarity illuminates a path forward together. Above all, solidarity transforms the downtrodden into a resounding chorus of citizens — in the spirit of voices who once gathered ‘round a white baby grand piano and sang, joyfully and loudly, “United We Stand.”

Robert W. Fieseler is a New Orleans-based journalist and the author of “Tinderbox: the Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation.”

homepage news

New Supreme Court term includes critical LGBTQ case with ‘terrifying’ consequences

Business owner seeks to decline services for same-sex weddings

The U.S. Supreme Court, after a decision overturning Roe v. Wade that still leaves many reeling, is starting a new term with justices slated to revisit the issue of LGBTQ rights.

In 303 Creative v. Elenis, the court will return to the issue of whether or not providers of custom-made goods can refuse service to LGBTQ customers on First Amendment grounds. In this case, the business owner is Lorie Smith, a website designer in Colorado who wants to opt out of providing her graphic design services for same-sex weddings despite the civil rights law in her state.

Jennifer Pizer, acting chief legal officer of Lambda Legal, said in an interview with the Blade, “it’s not too much to say an immeasurably huge amount is at stake” for LGBTQ people depending on the outcome of the case.

“This contrived idea that making custom goods, or offering a custom service, somehow tacitly conveys an endorsement of the person — if that were to be accepted, that would be a profound change in the law,” Pizer said. “And the stakes are very high because there are no practical, obvious, principled ways to limit that kind of an exception, and if the law isn’t clear in this regard, then the people who are at risk of experiencing discrimination have no security, no effective protection by having a non-discrimination laws, because at any moment, as one makes their way through the commercial marketplace, you don’t know whether a particular business person is going to refuse to serve you.”

The upcoming arguments and decision in the 303 Creative case mark a return to LGBTQ rights for the Supreme Court, which had no lawsuit to directly address the issue in its previous term, although many argued the Dobbs decision put LGBTQ rights in peril and threatened access to abortion for LGBTQ people.

And yet, the 303 Creative case is similar to other cases the Supreme Court has previously heard on the providers of services seeking the right to deny services based on First Amendment grounds, such as Masterpiece Cakeshop and Fulton v. City of Philadelphia. In both of those cases, however, the court issued narrow rulings on the facts of litigation, declining to issue sweeping rulings either upholding non-discrimination principles or First Amendment exemptions.

Pizer, who signed one of the friend-of-the-court briefs in opposition to 303 Creative, said the case is “similar in the goals” of the Masterpiece Cakeshop litigation on the basis they both seek exemptions to the same non-discrimination law that governs their business, the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act, or CADA, and seek “to further the social and political argument that they should be free to refuse same-sex couples or LGBTQ people in particular.”

“So there’s the legal goal, and it connects to the social and political goals and in that sense, it’s the same as Masterpiece,” Pizer said. “And so there are multiple problems with it again, as a legal matter, but also as a social matter, because as with the religion argument, it flows from the idea that having something to do with us is endorsing us.”

One difference: the Masterpiece Cakeshop litigation stemmed from an act of refusal of service after owner, Jack Phillips, declined to make a custom-made wedding cake for a same-sex couple for their upcoming wedding. No act of discrimination in the past, however, is present in the 303 Creative case. The owner seeks to put on her website a disclaimer she won’t provide services for same-sex weddings, signaling an intent to discriminate against same-sex couples rather than having done so.

As such, expect issues of standing — whether or not either party is personally aggrieved and able bring to a lawsuit — to be hashed out in arguments as well as whether the litigation is ripe for review as justices consider the case. It’s not hard to see U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts, who has sought to lead the court to reach less sweeping decisions (sometimes successfully, and sometimes in the Dobbs case not successfully) to push for a decision along these lines.

Another key difference: The 303 Creative case hinges on the argument of freedom of speech as opposed to the two-fold argument of freedom of speech and freedom of religious exercise in the Masterpiece Cakeshop litigation. Although 303 Creative requested in its petition to the Supreme Court review of both issues of speech and religion, justices elected only to take up the issue of free speech in granting a writ of certiorari (or agreement to take up a case). Justices also declined to accept another question in the petition request of review of the 1990 precedent in Smith v. Employment Division, which concluded states can enforce neutral generally applicable laws on citizens with religious objections without violating the First Amendment.

Representing 303 Creative in the lawsuit is Alliance Defending Freedom, a law firm that has sought to undermine civil rights laws for LGBTQ people with litigation seeking exemptions based on the First Amendment, such as the Masterpiece Cakeshop case.

Kristen Waggoner, president of Alliance Defending Freedom, wrote in a Sept. 12 legal brief signed by her and other attorneys that a decision in favor of 303 Creative boils down to a clear-cut violation of the First Amendment.

“Colorado and the United States still contend that CADA only regulates sales transactions,” the brief says. “But their cases do not apply because they involve non-expressive activities: selling BBQ, firing employees, restricting school attendance, limiting club memberships, and providing room access. Colorado’s own cases agree that the government may not use public-accommodation laws to affect a commercial actor’s speech.”

Pizer, however, pushed back strongly on the idea a decision in favor of 303 Creative would be as focused as Alliance Defending Freedom purports it would be, arguing it could open the door to widespread discrimination against LGBTQ people.

“One way to put it is art tends to be in the eye of the beholder,” Pizer said. “Is something of a craft, or is it art? I feel like I’m channeling Lily Tomlin. Remember ‘soup and art’? We have had an understanding that whether something is beautiful or not is not the determining factor about whether something is protected as artistic expression. There’s a legal test that recognizes if this is speech, whose speech is it, whose message is it? Would anyone who was hearing the speech or seeing the message understand it to be the message of the customer or of the merchants or craftsmen or business person?”

Despite the implications in the case for LGBTQ rights, 303 Creative may have supporters among LGBTQ people who consider themselves proponents of free speech.

One joint friend-of-the-court brief before the Supreme Court, written by Dale Carpenter, a law professor at Southern Methodist University who’s written in favor of LGBTQ rights, and Eugene Volokh, a First Amendment legal scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles, argues the case is an opportunity to affirm the First Amendment applies to goods and services that are uniquely expressive.

“Distinguishing expressive from non-expressive products in some contexts might be hard, but the Tenth Circuit agreed that Smith’s product does not present a hard case,” the brief says. “Yet that court (and Colorado) declined to recognize any exemption for products constituting speech. The Tenth Circuit has effectively recognized a state interest in subjecting the creation of speech itself to antidiscrimination laws.”

Oral arguments in the case aren’t yet set, but may be announced soon. Set to defend the state of Colorado and enforcement of its non-discrimination law in the case is Colorado Solicitor General Eric Reuel Olson. Just this week, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would grant the request to the U.S. solicitor general to present arguments before the justices on behalf of the Biden administration.

With a 6-3 conservative majority on the court that has recently scrapped the super-precedent guaranteeing the right to abortion, supporters of LGBTQ rights may think the outcome of the case is all but lost, especially amid widespread fears same-sex marriage would be next on the chopping block. After the U.S. Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against 303 Creative in the lawsuit, the simple action by the Supreme Court to grant review in the lawsuit suggests they are primed to issue a reversal and rule in favor of the company.

Pizer, acknowledging the call to action issued by LGBTQ groups in the aftermath of the Dobbs decision, conceded the current Supreme Court issuing the ruling in this case is “a terrifying prospect,” but cautioned the issue isn’t so much the makeup of the court but whether or not justices will continue down the path of abolishing case law.

“I think the question that we’re facing with respect to all of the cases or at least many of the cases that are in front of the court right now, is whether this court is going to continue on this radical sort of wrecking ball to the edifice of settled law and seemingly a goal of setting up whole new structures of what our basic legal principles are going to be. Are we going to have another term of that?” Pizer said. “And if so, that’s terrifying.”

homepage news

Kelley Robinson, a Black, queer woman, named president of Human Rights Campaign

Progressive activist a veteran of Planned Parenthood Action Fund

Kelley Robinson, a Black, queer woman and veteran of Planned Parenthood Action Fund, is to become the next president of the Human Rights Campaign, the nation’s leading LGBTQ group announced on Tuesday.

Robinson is set to become the ninth president of the Human Rights Campaign after having served as executive director of Planned Parenthood Action Fund and more than 12 years of experience as a leader in the progressive movement. She’ll be the first Black, queer woman to serve in that role.

“I’m honored and ready to lead HRC — and our more than three million member-advocates — as we continue working to achieve equality and liberation for all Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer people,” Robinson said. “This is a pivotal moment in our movement for equality for LGBTQ+ people. We, particularly our trans and BIPOC communities, are quite literally in the fight for our lives and facing unprecedented threats that seek to destroy us.”

The next Human Rights Campaign president is named as Democrats are performing well in polls in the mid-term elections after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, leaving an opening for the LGBTQ group to play a key role amid fears LGBTQ rights are next on the chopping block.

“The overturning of Roe v. Wade reminds us we are just one Supreme Court decision away from losing fundamental freedoms including the freedom to marry, voting rights, and privacy,” Robinson said. “We are facing a generational opportunity to rise to these challenges and create real, sustainable change. I believe that working together this change is possible right now. This next chapter of the Human Rights Campaign is about getting to freedom and liberation without any exceptions — and today I am making a promise and commitment to carry this work forward.”

The Human Rights Campaign announces its next president after a nearly year-long search process after the board of directors terminated its former president Alphonso David when he was ensnared in the sexual misconduct scandal that led former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo to resign. David has denied wrongdoing and filed a lawsuit against the LGBTQ group alleging racial discrimination.

-

State Department2 days ago

State Department2 days agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoJoe Vogel campaign holds ‘Big Gay Canvass Kickoff’

-

Politics3 days ago

Politics3 days agoSmithsonian staff concerned about future of LGBTQ programming amid GOP scrutiny

-

The White House1 day ago

The White House1 day agoWhite House debuts action plan targeting pollutants in drinking water