Eastern Europe

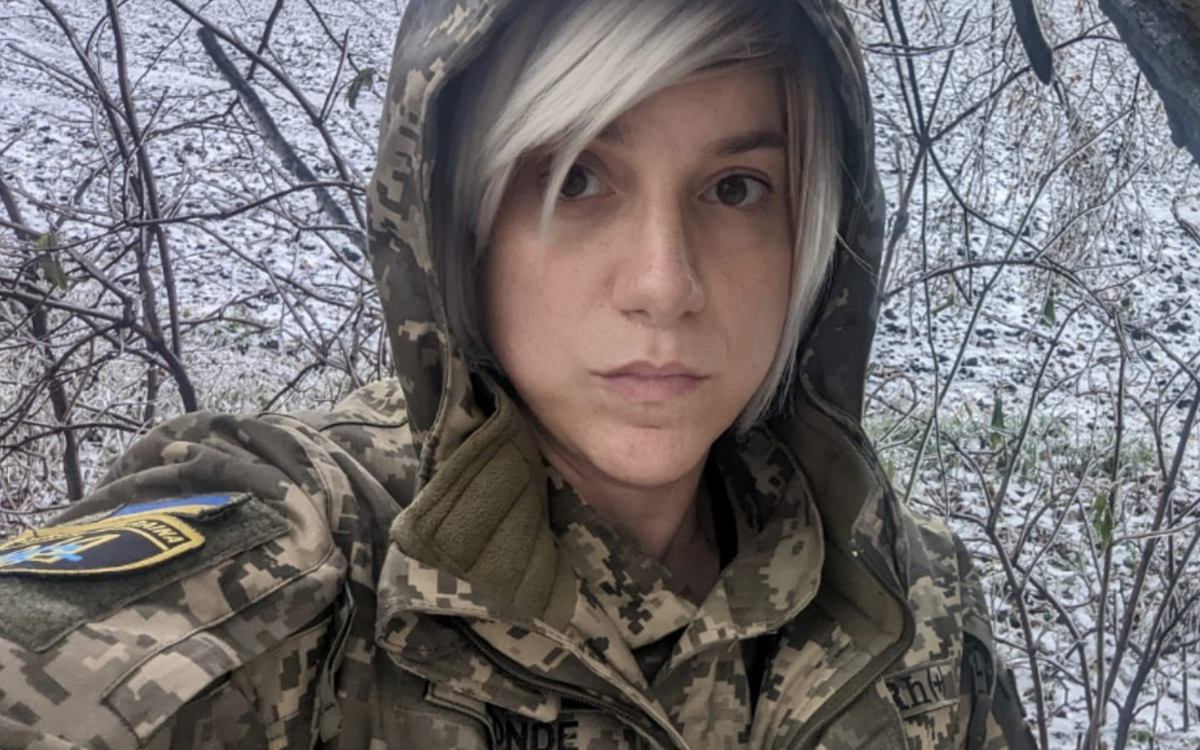

Transgender journalist joins Ukrainian military

Ashton-Cirillo tells the Blade, ‘I want to serve this fight for freedom, this fight for liberty’

It was shortly before 1 p.m. on Dec. 9 when Sarah Ashton-Cirillo, a member of the Armed Forces of Ukraine’s Noman Çelebicihan Battalion, arrived at Le Bon Café, a coffee shop on Second Street, S.E., near the U.S. Capitol. The Las Vegas native who was wearing her uniform sat down at an outdoor table and began to sip a coffee as she talked about the journey that brought her from the U.S. to the frontlines of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Ashton-Cirillo in 2015 traveled to eastern Turkey to cover Syrian refugees who had fled their country’s civil war.

She said she was “supposed to have started the story in Syria, but I was too scared.” Ashton-Cirillo later wrote a book, “Along the Tracks of Tears,” but she told the Washington Blade that she “was terribly unhappy with” it.

“Some of it had to do with being trans,” she said. “I had been traveling with Muslims, with different groups, and they were accepting me, but I would always have in the back of my mind, would they have talked to me if they knew I was trans or a female.”

Ashton-Cirillo, who was born in northern Florida, was the director of communications for a California-based health care company before she launched Political.tips, a website that focused on politics in Nevada and across the country. Ashton-Cirillo has also sought to expose extremist Republicans through her reporting.

‘I was not expecting it to happen’

Ashton-Cirillo noted she wrote her second book, “Fair Right Just,” while she was in the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.) Ashton-Cirillo told the Blade that she learned about what Russia had done to them through mid-winter visits to museums.

“That led me to hate Russia, because I’m reading about things that ended up being pertinent today: Filtration camps, the language issues, they were trying to erase culture, the genocide, the torture of political prisoners, everything that we’re living now, the folks in the Baltics lived 80 or 90 years ago, as do the Ukrainians, but I hadn’t been to Ukraine yet.”

Russia launched its war against Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022.

“It always bothered me for 6 1/2 years,” said Ashton-Cirillo, referring to her book about Syrian refugees. “As I was watching this unfold, I said, oh, there’s a massive refugee situation. Is it worth it for me to go over and try to maybe get new material and put out a book that would actually take the old material and the new material and put it together. I put it together, and so when the war actually broke out, I said, holy shit this is real and that’s why I wasn’t here (in Ukraine) on the first day. I was watching it.”

Ashton-Cirillo conceded she is “the first to say I was not expecting it to happen.”

“With the full-scale invasion happening on Feb. 24, even though Donbass had been under siege, and there had been a war going on for or years, I didn’t expect there to be an invasion, a land invasion of a full country, not just in this area that had been, you know, that the Russians had seized when basically the world was sleeping,” she said.

Ashton-Cirillo entered Ukraine on March 4, 2022, with the intention of covering refugees who had fled the country. She said the press credentials the Ukrainian government reflected her gender identity and her legal name.

“My legal name, Sarah Ashton-Cirillo, was my legal name when I traveled. My gender was my legal gender when I traveled due to having changed it in Nevada,” said Ashton-Cirillo. “My driver’s license was changed but my passport had not been changed … it was very complicated because it looked like a totally different person with totally different names, a totally different gender.”

Ashton-Cirillo noted Ukrainian officials put her legal name on the top of her press credentials and “formally known as my previous name” on the bottom of them.

“I was okay with it because I couldn’t believe they credentialed me anyway with the situation being the way it was,” she said.

Jessica Stern, the special U.S. envoy for the promotion of LGBTQ and intersex rights, less than a month after the war began told the Blade that many trans and gender non-conforming Ukrainians decided to remain in the country because they could not exempt themselves from military conscription. Stern during the March 18, 2022, interview cited the case of a trans man who tried to leave Ukraine and “in an effort to prove who he was, who he said he was, he was actually forced to remove his shirt and show his chest” at the border.

“Unfortunately, that’s not the only humiliating and potentially violent incident that I’m hearing,” she said.

One of the stories that Ashton-Cirillo wrote for LGBTQ Nation while in Ukraine highlighted problems that trans people had when they tried to leave the country because their ID documents did not match their gender identity.

Gender Stream, a Ukrainian advocacy group, helped more than 50 trans and nonbinary people obtain the necessary paperwork that allowed them to leave the country. Ashton-Cirillo acknowledged there was “gatekeeping, but people could get out.”

“Nobody knew what to do,” she said, referring to the treatment of trans and nonbinary Ukrainians who wanted to leave the country immediately after the war began. “Every male was mobilized. It was just something I don’t think was ever going to come up in the purview. The other thing not coming up in the purview was getting a trans journalist popping in with an ID that was totally different. I didn’t expect to get let in. I didn’t expect to get credentialed.”

Russian airstrike killed activist days before Ashton-Cirillo arrived in Kharkiv

Ashton-Cirillo told the Blade that she wanted to go to Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, and cover Russia’s efforts to seize it. Ashton-Cirillo instead traveled to Kharkiv, the country’s second largest city that is less than 30 miles from the Russian border in eastern Ukraine.

Elvira Schemur, a volunteer for Kyiv Pride and Kharkiv Pride, was inside the regional administration building in Kharkiv on March 1, 2022, when a Russian missile struck it. The 21-year-old law student was among those who were killed.

Ashton-Cirillo arrived in Kharkiv eight days after Scheumer’s death.

CNN Chief International Correspondent Clarissa Ward was among the journalists who reported from Kharkiv during the first weeks of the war. Ashton-Cirillo recalled to the Blade a conversation that she had with her shortly after she arrived in the city.

“Clarissa says to me, via the Twitter Space, Sarah, I’ve been following your work in Kharkiv. It’s great,” recalled Ashton-Cirillo. “If you don’t leave you’re going to be traumatized for the rest of your life because this is the worst bombing … she knows it.”

“She’s an idol of mine,” she added. “She’s somebody that I look up to from a journalistic standpoint … I didn’t understand what that meant because I’m embedded with security services and not only am I trans, I’m living with security forces during the bombings as a trans woman and a journalist and I’m living with them. I was seeing things that no one else was seeing, but I was also living in a bubble and because of that I was living this life of war and I was living this life of terrorism and death every single day, but I didn’t realize it.”

Ashton-Cirillo said the only foreigner she saw from the time she arrived in Kharkiv until April 21 was an Al-Jazeera reporter who visited the same site that Russia had attacked.

“I was in a bubble and didn’t realize what I was going through was not normal,” she said. “It was not normal because journalists come in and out, they have each other to talk with. I was totally on my own.”

Ashton-Cirillo lived and worked with local security officials. She also helped them deliver weapons to checkpoints while she was not writing about the war.

The mayor of Zolochiv, a village in Kharkiv Oblast that is 10 miles from the Russian border, named Ashton-Cirillo his official representative in negotiations with foreign aid groups after he met her. She said there “was devastation” in the village when she first arrived.

“I’m on the Russian border and I’m being empowered as power of attorney for this town of Zolochiv. This was my focus in between my writing,” she said. “I would go up there and do my things, but I was not a combatant yet.”

Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson targets Ashton-Cirillo

Russia’s castration of gay Ukrainian men and hunt lists for LGBTQ and intersex people in Mariupol and other cities are among the stories that Ashton-Cirillo wrote for LGBTQ Nation.

She notes in one LGBTQ Nation article that Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova on April 21 publicly accused her of participating in the disappearance of journalist Gonzalo Lira, who, she noted “was being held by Ukrainian State Security services.” Zakharova, according to Ashton-Cirillo, described her as a “transgender journalist from Las Vegas” who took pictures with “gangsters,” a reference to Ukrainian soldiers.

“It made me cry. It was the first time I cried,” Ashton-Cirillo told the Blade. “It was the worst and then it unleashed right-wing trolls. Glenn Greenwald jumped on it.”

Joe Oltmann, a Denver-based podcast host, falsely accused Ashton-Cirillo of murdering Lira. Ashton-Cirillo has filed a defamation lawsuit against the prominent 2020 election denier.

“All this insanity was going on and I’m crying,” said Ashton-Cirillo.

She said a member of the Azov Regiment, a Ukrainian National Guard unit that defended the port city of Mariupol during the Russian siege, asked her why she was crying.

“You come out to the rocket attacks. You see dead bodies. You don’t cry,” he said.

“Maria Zakharova attacked me,” said Ashton-Cirillo.

“I’m so proud of you because that means you’re really getting to them,” responded the Azov Regiment member.

Ashton-Cirillo told the Blade the conversation “changed my whole mindset.”

Ashton-Cirillo soon began to work for the Kharkiv Media Hub, which supports journalists who are working in the city. Ashton-Cirillo also continued her work with Zolochiv and NGOs, including José Andrés’ World Central Kitchen, once they reached areas that Ukrainian forces had liberated from Russia.

“I was so proud to see these guys,” she said, referring to World Central Kitchen. “This organization gets it.”

Ashton-Cirillo began to work for the Ukrainian Defense Ministry in a civilian capacity in August. She continued to represent Zolochiv.

“My mind wasn’t on the stories anymore,” said Ashton-Cirillo. “I knew how much work I was doing for the government. I pushed the envelope as far as I could without, I think, getting into an ethical dilemma from a journalistic standpoint because I love journalism.”

Ashton-Cirillo said discussions about her enlisting in the Armed Forces of Ukraine were already taking place when the Kharkiv counteroffensive began in September. Ashton-Cirillo told the Blade that she also worked to counter Russian propaganda that included the claim that Russian troops had captured Bakhmut, a city in Donetsk Oblast.

“I’m in Bakhmut. Fighting is literally all around. I’m standing there grinning at City Hall, look, Russia doesn’t have it. It’s lies,” she recalled. “I get a phone call that night, we’re ready to enlist you.”

A journalist drove Ashton-Cirillo from Bakhmut to Kyiv.

“I had never been to Kyiv,” she said. “I get to Kyiv, and it’s bustling and its amazing. I was frozen with disbelief. Wow, Kyiv is great.”

Ashton-Cirillo was in Kyiv on Oct. 10 when Russia launched a rocket attack against Kyiv. She said one of the rockets landed less than 700 feet from the apartment in which she was staying. Ashton-Cirillo was the first journalist on the scene.

“I had my credentials with me and I had my vest and my helmet and I did a video that was viewed millions of times,” she said, noting President Volodymyr Zelenskyy shared it on his official Instagram page and Ukrainian television stations broadcast it on their nightly news casts. “That was it. That was my last journalistic endeavor.”

Ashton-Cirillo a short time later went to a recruiting station to enlist.

She said a commander who brought her there told her she will “have to prove yourself.” Ashton-Cirillo told him that she was willing to join a frontline unit, she could march 30 km. with a 20 kg. backpack and she was willing to kill someone.

“One of the reasons I was willing to join is because the war became so personal,” she said, noting she had conducted interviews while rocket attacks and shelling was taking place. “I knew how to shoot. I’m a country girl from the South, so I know how to shoot. Country girl will survive.”

“I want to serve this fight for freedom, this fight for liberty, this fight for all of us,” added Ashton-Cirillo. “As a trans person I want to survive, but most specifically as a human being … it became personal, and I was a citizen of Kharkiv. I was a citizen of Kharkiv Oblast and all of us went through something horrifying, life-changingly traumatic and I was ready.”

Ashton-Cirillo described her commander as a “huge champion of mine.” She told the Blade he asked his colonel whether her gender identity mattered.

“He said no,” recalled Ashton-Cirillo. “I told you she looks healthy. That was it.”

She had a standard physical at a military hospital the next day and “no one batted an eyelash.” Ashton-Cirillo passed, and had 1 1/2 days to return to Kharkiv to get her belongings before she reported to her base.

She is a combat medic because of her background in health care.

“We’re in the field,” she said. “I’m not at the front currently. However, we all live together. Every one of the soldiers knows I’m trans. Some people are completely great with it.”

Ashton-Cirillo — who speaks with her fellow soldiers through Google Translate, English or another language, such as German or Spanish, because she does not speak Ukrainian — said some of them have asked her why she is trans and for how long she has known about her gender identity. Ashton-Cirillo described these questions as “genuine curiosity.” She also said “everybody was cheering me on” when Russian state media last month once again featured her.

“They had me shooting machine guns. They had my training videos and that we’re coming to Crimea,” recalled Ashton-Cirillo. “It backfired so badly on them because it was almost as though you paid them to publish this because you managed to say on Russian television ‘Slava Ukraini’ (‘Glory to Ukraine’) twice. What better publicity and they allowed me to say we’re going to Crimea.”

The Blade spoke with Ashton-Cirillo while she was in D.C. to speak with lawmakers on behalf of the Ukrainian Defense Ministry about continued support for Ukraine.

Ashton-Cirillo met with U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), members of U.S. Sen. Jim Risch (R-Idaho)’s staff and other lawmakers or their senior aides.

“We were focused on Ukraine,” said Ashton-Cirillo. “I’m here in a nonpartisan manner. I’m here representing Ukraine’s interests, so we can win this war with our greatest ally, the United States. They met with me.”

“The senator and the senator’s staff were absolutely amazing with me and not in a fictitious way,” she said. “We got down to business.”

Ashton-Cirillo told the Blade that her gender identity was not discussed.

“I haven’t been focused on identity for 9 and 1/2 months,” she said. “I’m sitting in your office. I want to say thank you for your support of Ukraine.”

Ashton-Cirillo also met with activists and NGO representatives in D.C. She traveled to New York; Austin, Texas, and Las Vegas, where she visited her child, before she flew back to Poland on Tuesday.

Ashton-Cirillo once she landed in Warsaw picked up an ambulance that drove into Ukraine the following day.

Zelenskyy on Wednesday met with President Joe Biden at the White House. The Ukrainian president also spoke to Congress before he left D.C.

Zelenskyy after he met with Biden at the White House in 2021 pledged Ukraine would continue to fight discrimination based on sexual orientation. (Ukraine since 2015 has banned employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.)

Zelenskyy over the summer announced he supports civil partnerships for same-sex couples. Ukrainian lawmakers last week unanimously approved a media regulation bill that will ban hate speech and incitement based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

“President Zelenskyy’s response to the civil partnership petition shows his commitment to human rights and the rule of law,” Ashton-Cirillo told the Blade on Wednesday in a WhatsApp message. “He could have avoided answering or hiding behind the ongoing war against the Russian invaders but instead gave a clear response based on dignity and liberty.”

“In Ukraine it is key to remember this is a society that is literally fighting for liberation, for all its citizens,” she said. “The new media law is an extension of that.”

Ashton-Cirillo further stressed that Ukraine “cares about humanity, Putin and his war criminals don’t.”

“The separation between the two societies are clear,” she said. “Life in Ukraine is not about tolerance but about freedom. And now the broader world is beginning to realize this as every new civil rights advance takes place.”

Eastern Europe

LGBTQ Ukrainians bear brunt of psychological toll amid ongoing war

Saturday marks two years since Russia invaded country

As Ukraine weathers Russian missile attacks and endures a harsh winter, the psychological consequences on its LGBTQ community are emerging as a distressing and often overlooked aspect of the conflict.

Recent reports from Human Rights First, based on their visits to the northeastern Ukrainian region of Kharkiv, shed light on the profound emotional impact experienced by LGBTQ individuals amid the sustained Russian aggression.

Saturday marks two years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. Throughout this time, Human Rights First has sought to bring human rights into the heart of the discussion surrounding the conflict, offering support to human rights defenders, activist organizations, and individuals profoundly affected by the war.

Human Rights First last November initially surveyed Kharkiv to understand how communities were preparing for the harsh winter. Returning last month they found the LGBTQ community faced not only the physical challenges of extreme temperatures but also the hidden harm of severe psychological distress.

Human rights defenders on the forefront were documenting war crimes and supporting marginalized communities, including LGBTQ individuals. They emphasized the critical need for specialized psychological support within this community.

Vasyl Malikov, a key figure in Kharkiv-based LGBTQ NGOs Alliance.Global and Spectrum Women’s Association in Kharkiv, spoke about the increasing requests for psychological assistance and counseling.

Malikov highlighted the urgent need for both psychologists and a more comprehensive education about mental health and trauma issues.

“Some counseling can be done online, and it’s better than nothing, but what’s really needed is face-to-face time with a psychologist. Of course, that’s resource-intensive,” Malikov said, underscoring the unique challenges faced by the LGBTQ community.

Associate Professor Taras Zhvaniia, collaborating with Alliance.Global, shared insights into the growing demand for psychological support within the LGBTQ community. Initially addressing trauma in children, the scope expanded to include adults grappling with anxiety, depression and other emotional challenges related to the ongoing conflict.

Zhvaniia detailed the psychological struggles unique to the LGBTQ community, ranging from anxiety and panic attacks to specific fears such as reluctance to sleep in beds at home, avoiding bomb shelters and apprehension about routine activities during shelling.

Efforts to increase psychological knowledge for the general population are underway, yet the escalating demand for LGBTQ-focused support outpaces available resources. Human rights defenders have proposed measures, including funding for online counseling and visits by foreign psychologists, specifically tailored to address the psychological impact on the LGBTQ community.

The silent struggle faced by the LGBTQ community in Kharkiv and beyond necessitates international attention, according to Human Rights First. The organization added the lack of adequately trained psychologists raises concerns about the unaddressed psychological impact, underscoring the urgency for U.S. officials and the international community to comprehend and respond to the unique challenges faced by LGBTQ individuals in the midst of the ongoing conflict.

Eastern Europe

LGBTQ community in Kharkiv braces for another winter at war

Ukrainian city is 30 miles from Russian border

KHARKIV, Ukraine — Only 30 miles from the Russian border, Kharkiv is Ukraine’s second biggest city and was a key target of Russia’s invasion in February last year, when it was almost encircled.

I have been reporting regularly from Kharkiv since last year’s full-scale invasion, and the city is still often bombed by Russian missiles. United States government officials rarely come here because of the security situation. As temperatures plummet, Russia is targeting Ukraine’s heating infrastructure.

It hopes to make life unbearable for people in Ukraine’s cities and force another wave of mass movement out of Ukraine and into Poland and other European countries.

Attacks on Ukraine’s energy grid have begun, and some communities in the city have been particularly vulnerable since Russia’s invasion last year, and are facing a difficult winter.

Vasyl Malikov of the Kharkiv-based LGBTQI NGOs Alliance.Global and Spectrum Kharkiv has been distributing packages of hygiene goods, food and vouchers for humanitarian aid since last year. He helped to set up a new shelter for LGBTQI people and their relatives in the city.

“There are government shelters, and the authorities say they don’t discriminate against who uses them, but we know from lived experience that these official shelters aren’t always welcoming places for LGBTQI people. They feel vulnerable and are harassed there,” Malikov said. “We thought about setting up a shelter last year, but the situation seemed too uncertain and it wasn’t that easy to find premises, but we have gone ahead now and we can offer accommodation for up to 16 people to stay for up to three months.”

Some of those in the shelter are fleeing areas of conflict on the front lines, others have fled domestic violence, and others have been driven away by families who refuse to accept them. Some people, in Kharkiv for medical appointments, stay for days, others stay for weeks or months.

The shelter is a large apartment that has a kitchen and a large room where workshops and social events are held. It is on a block near a metro station which, Malikov says, is a useful place to run to in case of heavy bombardments.

Crucially, a new generator has arrived, which should heat the shelter during power outages. It’s a dual fuel model that can run on diesel or gas and costs around $2,000.

“This is a safe place for LGBTQI people and their families,” explains Malikov. “We shouldn’t have to set up our own facilities, the authorities should be doing this work, but we have to because they don’t.”

Other NGOs are also filling gaps that local authorities are failing to provide. The NGO Sphere has, since 2006 “been uniting women of Kharkiv, including lesbian and bisexual women.”

Tucked in a small office near the city center, some of Sphere’s activists described how their work has adapted to meet the challenges of the war.

“We’ve been providing aid for those forced to flee their homes because of the war,” says Yevheniia Ilinska, a long-standing member of the organization. “We’ve raised money from abroad — including from LGBTQ+ groups — to distribute basic supplies. We’ve been handing out clothes, including socks, and have provided some to our military.”

Sphere’s activists say that beyond its obvious damage and destruction to the city, the war is causing “a social revolution:” many men are away from their homes fighting in the military, and many family dynamics are changing dramatically.

The activists fear a spike in domestic violence when soldiers return home, a phenomenon witnessed in other countries.

“The full-scale war significantly aggravates some of the problems that existed before, including gender-based domestic and sexual violence, and discrimination at work,” Sphere notes on its website.

The war has also helped change some attitudes towards LGBTQ+ people in Ukraine. Last September, when the dangers from rocket attacks made an open-air parade impossible, Sphere helped organize a successful Pride event in the city’s metro system.

“We dressed wearing national symbols and LGBT flags,” says Ilinska. “And the public reception was very positive.”

The reaction is more evidence of a positive shift since last year’s invasion in public attitudes towards LGBTQ+ people, in part because the community’s contribution to the war effort is increasingly seen and valued. Hopes are high that Ukraine will soon legalize same-sex civic partnerships, and eventually same-sex marriages.

But for now, the cold is an immediate challenge. Sphere is raising funds to offer locals a safe place so that “in the event of rocket attacks and power outages, LGBTQ+ people will be able to stay warm indoors, have a hot drink, take a shower, and do laundry,” says Ilinska.

“We’re constantly adapting our work,” says Ilinska. “Adapting our advocacy and our public events, and our projects on targeting humanitarian aid. Kharkiv is changing and so are we, we have to react to this dramatic crisis, to the invasion, and we’re proving that we and our community can resist,” she said.

For more, see Human Rights First’s new report, Ukraine’s Winter War, written by Maya Fernandez-Powell and myself.

Eastern Europe

Transgender soldier from US named Ukrainian military spokesperson

Sarah Ashton-Cirillo was journalist before she enlisted

The Armed Forces of Ukraine have named a transgender soldier from the U.S. as one of its English-speaking spokespeople.

The Kyiv Post, an English-language newspaper, last week in a tweet noted Sarah Ashton-Cirillo “has become one of the speakers for the Defense Forces.” Deputy Defense Minister Hanna Malyar is among those who praised Ashton-Cirillo.

“Sara informs the English-speaking audience — she objectively covers the events of the Russian-Ukrainian war, debunks Russian fakes and propaganda,” said Malyar, according to the Kyiv Post. “Sarah’s audience reach on Twitter alone was 28.3 million users. So, the enemies get excited on hateful social networks, of course. However, this has only increased Sarah’s audience.”

Ashton-Cirillo was a journalist when she began to cover the Armed Forces of Ukraine’s Kharkiv Defense Forces at the beginning of Russia’s war against the country in 2022. She eventually enlisted, and a commander from the Defense Ministry on Jan. 31, 2023, facilitated her transfer to the unit’s 209th Batallion of the 113th Brigade.

Ashton-Cirillo, who was born in New York, was working as a senior combat medic in a trench near Kreminna in eastern Ukraine on Feb. 23, 2023, when shrapnel from an enemy artillery shell wounded her. Ashton-Cirillo suffered injuries to her right hand and to her face, and her fellow soldiers had to wait seven hours to evacuate her. Ashton-Cirillo eventually received treatment for her injuries in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city that is roughly 130 miles northwest of Kreminna.

The Washington Blade spoke with Ashton-Cirillo in May while she was in D.C.

“The big key there was I wasn’t able to take any painkiller by staying in the trench because I was still technically in battle,” she recalled. “Seven hours after my injury, I finally got to a hospital.”

Ashton-Cirillo on Tuesday told the Blade her “new role within the Armed Forces of Ukraine is a position that has been earned due to my performance on the physical and informational battlefields.”

“What this means is that in today’s Ukraine being a part of the LGBTQ community is neither a benefit nor hindrance, but simply an accepted part of whom a person is,” she said. “The vocal support shown by LGBTQ groups in Ukraine, such as Gender Stream, Kyiv Pride and Ukraine Pride, upon news of this taking place, along with the statement of confidence in me issued by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense and Deputy Defense Minister Hanna Maliar, made me understand that this battle for the country’s liberation is not about tolerance or acceptance for any one group but freedom and liberty for all Ukrainians.”

-

South America4 days ago

South America4 days agoDaniel Zamudio murderer’s parole request denied

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoMontgomery County police chief discusses arrest of trans student charged with planned school shooting

-

State Department1 day ago

State Department1 day agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

Theater4 days ago

Theater4 days ago‘Amm(i)gone’ explores family, queerness, and faith