History

200-year-old journal challenges notions about historical attitudes toward homosexuality

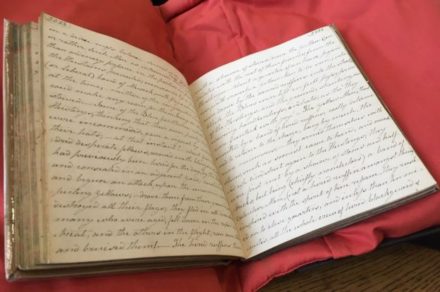

The writings of a Yorkshire farmer in a 200-year-old journal have revealed that historical attitudes toward homosexuality may have been more sympathetic than previously suspected – at least in Great Britain.

BBC News reports that historians from Oxford University were taken aback by entries in the 1810 diary of Matthew Tomlinson, a widower in his 40s with “middling income” whose writings expressed comparatively open-minded views about same-sex attraction, including saying that he regarded it as being a “natural” human tendency.

The discovery challenges preconceived notions about how “ordinary people” viewed homosexuality, revealing that there was wider debate over the subject than previously assumed. Although more accepting views toward homosexuality are known to have been expressed privately by more educated, “philosophically radical” individuals of the era, and though Tomlinson was writing around the same time as that of another Yorkshire diarist, Anne Lister, who wrote coded details of her lesbian relationships into her own journal, the idea of a rural worker even having such opinions, let alone being willing to express them, is one which shifts the perspective on the way LGBTQ people have been viewed in history.

Oxford researcher Eamonn O’Keeffe, a doctoral student who has been examining the diary, told the BBC that the diary shows liberal ideas about homosexuality were “percolating through British society much earlier and more widely than we’d expect.”

“In this exciting new discovery,” he said, “we see a Yorkshire farmer arguing that homosexuality is innate and something that shouldn’t be punished by death.

“What’s striking is that he’s an ordinary guy, he’s not a member of the bohemian circles or an intellectual. It shows opinions of people in the past were not as monolithic as we might think – even though this was a time of persecution and intolerance towards same-sex relationships, here’s an ordinary person who is swimming against the current and sees what he reads in the paper and questions those assumptions.”

Tomlinson’s private diaries, which span the years 1806 – 1839, have been in Yorkshire’s Wakefield Library since the 1950s and are presumed to be part of an earlier acquisition of old books and documents. There are three surviving volumes, with another eight presumably lost.

The entries in question concern a scandal of the day in which a respected naval surgeon had been court-martialed and sentenced to death after being caught engaging in homosexual activity. In his journal, the farmer expressed his Tomlinson dissatisfaction with the decision, questioning the newspapers’ characterization of such behavior as “unnatural,” and arguing from a religious perspective that punishing someone for how they were created was implied that the Creator Himself was at fault.

In an entry from January 14, 1810, he wrote, “It must seem strange indeed that God Almighty should make a being with such a nature, or such a defect in nature; and at the same time make a decree that if that being whom he had formed, should at any time follow the dictates of that Nature, with which he was formed, he should be punished with death.”

The farmer went on to write that if there was an “inclination and propensity” for someone to be homosexual from an early age, “it must then be considered as natural, otherwise as a defect in nature – and if natural, or a defect in nature, it seems cruel to punish that defect with death”. Tomlinson also refers to being informed by others that homosexuality is apparent from an early age – indicating there had been discussions between the diarist and members of his social circle about the case, and that the subject matter was not unknown to them.

As forward-thinking as his opinions might seem, the 19th-century farmer still had plenty of room to evolve. He also made what O’Keefe calls the “extremely jarring” concession that if someone was homosexual “by choice, rather than by nature,” that he was willing to consider punishment as an acceptable option – though he favored the “more moderate” approach of castrating the offender, rather than sentencing them to death by hanging.

Still, O’Keefe says the discovery has both “enriched and complicated” our understanding of public opinion in the pre-Victorian era.

The journal has drawn international interest from historians, such as LGBTQ history expert Rictor Norton, who said, “It is extraordinary to find an ordinary, casual observer in 1810 seriously considering the possibility that sexuality is innate and making arguments for decriminalization.”

History

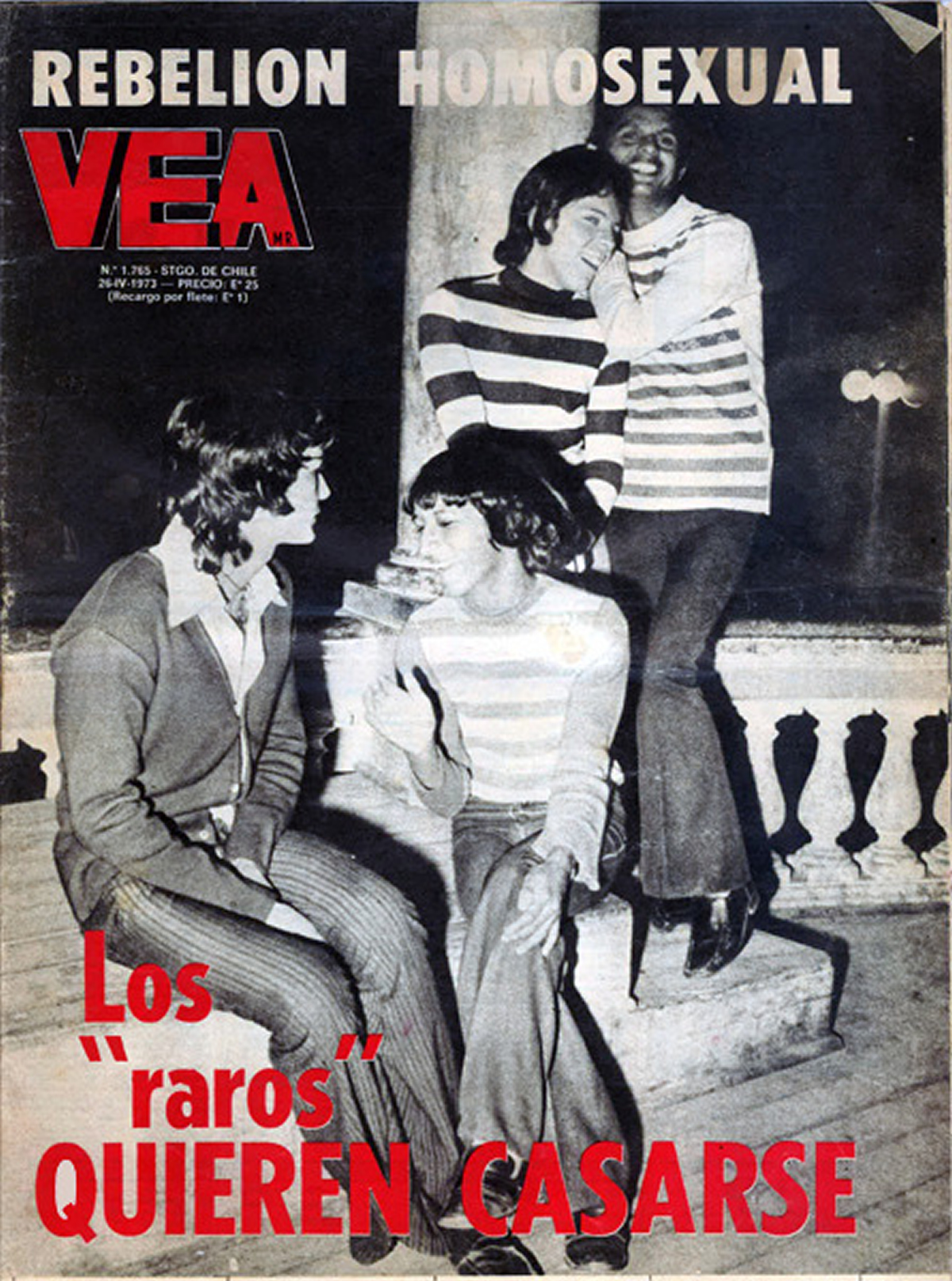

‘Las Locas del 73’ documents historic LGBTQ rights protest in Chile

Demonstration took place months before 1973 coup

In a year of deep reflection and commemoration of two crucial moments in Chile’s history, “Las Locas del 73” documents the 50th anniversary of the country’s first gay rights march that took place months before the 1973 coup.

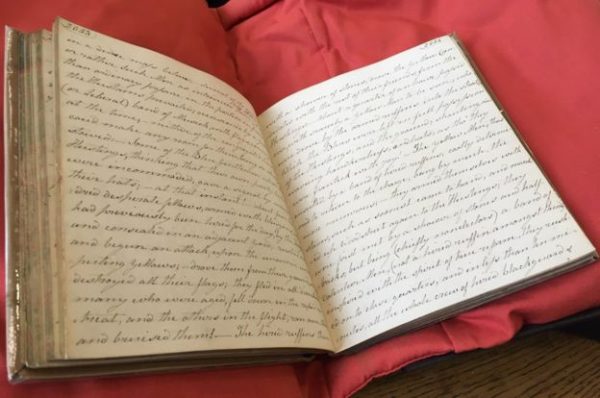

Victor Hugo Robles, who is also known as El Che de los Gays, co-directed the documentary with documentarian Carolina Espinoza that Sociedad Sonora, a production company, helped release in Chile and Spain on April 22, the 50th anniversary of the protest. The documentary has proven to be a resounding success, and film festivals in several countries are planning to screen it in the coming months.

This documentary is a doubly significant tribute.

It not only tells the courageous story of a group of gay and transgender Chileans who, on April 22, 1973, protested against social discrimination and police repression, but also highlights the intricate connection between this struggle and the traumatic coup that forever changed Chile’s destiny.

Raquel, Eva, Larguero, Romané, José Caballo, Vanesa, Fresia Soto, Confort, Natacha, Peggy Cordero and Gitana were the protagonists of what the media at the time described as the scandalous demonstration that took place in Santiago’s Plaza de Armas, a commercial area that families frequented on Sundays, on that fall Sunday afternoon. The coup took place less than five months later, on Sept. 11, 1973.

Most LGBTQ Chileans at that time were in the closet.

Discrimination was so widespread that nobody dared to publicly disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity. (Consensual same-sex sexual relations were punishable with prison until their decriminalization in the country’s penal code in 1999.) Police at that time routinely raided private meetings of LGBTQ people and “indecency” arrests were commonplace.

While the media at the time highly publicized the iconic protest, it was something of an urban myth among LGBTQ Chileans until the 1990s. It was said a “group of crazy women” had staged a rebellion in the 1970s, but there was no clarity about the exact date. It seemed to be a story without protagonists, a local legend subject to exaggerations and reversions.

It was this ambiguity that aroused Robles’ curiosity, and he began to investigate and reconstruct the episode.

“I heard many stories that there had been a gay protest during the time of Salvador Allende, but no one was certain,” Robles told the Washington Blade. “I spent a lot of time researching this protest. It took me a long time. I would say it took me more than a year, almost two years to find the exact moment because I had to go to the newspapers of that time. You had to ask for them at the library and go through them newspaper by newspaper, month by month, and it took a long time to fetch the newspapers from the warehouse.”

He added that “everything is now digitized, but at that time nothing (was), so I started to check the newspaper because everything was in the newspaper itself.”

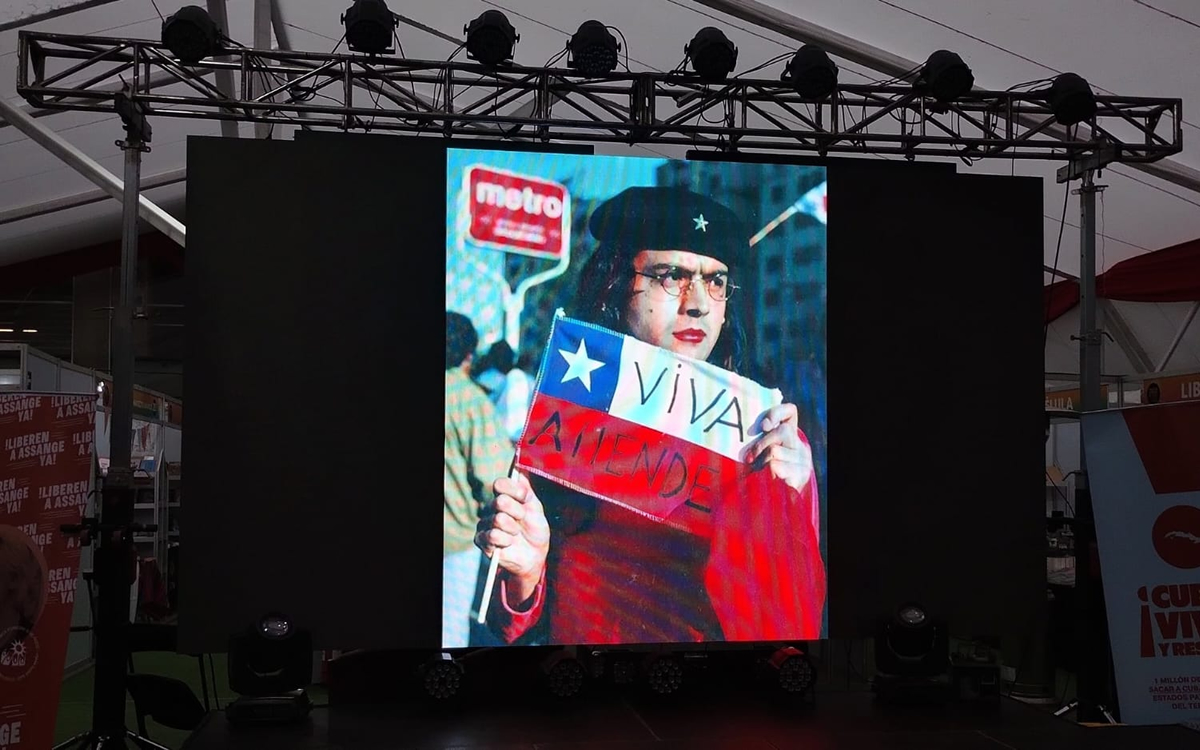

“Everyone talks about Clarín, which was the most important newspaper of the time, with a huge circulation. It was a popular media outlet; with sarcastic, direct, ironic, humorous language,” said Robles. “Then I started to look at Clarín, month by month, in 1970, 1971 and 1972.”

Robles told the Blade he was already giving up in his search when a friend gave him a clue that would end up uncovering valuable information for the reconstruction of the history of the Chilean LGBTQ movement.

“I was almost giving up until a friend gave me the tip about Paloma magazine, which was the leftist magazine of the time, a communist magazine, and that’s where the protest had come out,” said Robles. “He remembered having read it there.”

He recalled his expectations increased again after this revelation because he knew that that magazine had fewer editions — one per month, which increased the chances of finding what he was looking for more quickly.

“That’s when I came across the news. It said: ‘Homosexuals on the offensive.’ A very small article and … they pointed out the exact date. That demonstration, that protest, then appeared and it was dated Sunday, April 22, 1973.″

“Immediately, with the date in hand, I went to Clarín newspaper and, indeed, it was there. It was on the front page two days after the protest took place, on April 24, 1973,″ he recalled emotionally.

That front page to which the Chilean journalist referred exposed the existing homophobia in society.

“Homosexuals ask for the moon,” read Clarín’s headline.

Clarín was a progressive, leftist newspaper that supported President Salvador Allende.

The newspaper’s slogan proclaimed it was “on the people’s side.” Pinochet’s dictatorship immediately shut down Clarín after the coup.

“The loose mares, lost madwomen, anxious for publicity, launched headlong, met to demand that the authorities give them a chance, a shot and a side for their deviations,” read the Clarín article about the protest.

The police did not show up, even though the meeting had been well publicized.

The media reports continued with more insidiousness.

“At first the sodomites, believing that the police contingent would fall on them at every moment, were cautious. But they quickly loosened their braids … and launched themselves, demonstrating that the freedom they demand is nothing more than licentiousness. Homosexuals, among other things, want legislation to allow them to get married and do a thousand and one things without police persecution. What a mess that would be. No wonder an old man proposed spraying them with kerosene and throwing a lit match at them,” wrote Clarín.

Newspaper reports said mothers covered their children’s eyes so that “they would not witness such a horrendous spectacle.”

But it was not only in Clarín.

“I realized that it had been covered by quite a few media outlets, by the Puro Chile newspaper, for example. It also appeared later on the cover of Vea magazine, which was very important at the time,” said Robles.

That demonstration marked a turning point in the struggle for the rights of sexual minorities in Chile, a path that remains relevant and valid to this day. The film pays tribute to the brave activists who, for the first time in Chilean history, stood up against social discrimination and social repression.

La Medallita, Brenda, Marco Ruiz and Marcela Dimonti are among those who narrate the documentary.

Dimonti, besides being a prominent figure in the struggle for LGBTQ rights, was a prisoner inside the National Stadium after the coup.

History

AIDS @40: White House laughs as gays try to save themselves

Reagan administration ignored growing epidemic

Editor’s note: This is the fourth and final installment of this special series looking back at 40 years of AIDS. Visit washingtonblade.com for the previous installments.

Like so many others in California, lesbian feminist Ivy Bottini had high expectations for the federal government to finally intervene in the growing AIDS crisis after the first congressional committee hearing on the mysterious new disease, chaired by Rep. Henry Waxman on April 13, 1982. There was very little press coverage of the hearing — held at the Los Angeles Gay Community Services Center on Highland Ave. in Hollywood. But years later, Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health recalled a quote reported by the Washington Blade: “I want to be especially blunt about the political aspects of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS),” Waxman said. “This horrible disease afflicts members of one of the nation’s most stigmatized and discriminated-against minorities….There is no doubt in my mind that if the same disease had appeared among Americans of Norwegian descent, or among tennis players, rather than among gay males, the responses of the government and the medical community would have been different.”

The gay San Francisco newspaper The Sentinel published a very short brief on April 16 entitled “House Holds Cancer Hearings” about “the gay cancer.” The paper quoted an unnamed subcommittee staffer saying the CDC, “which is coordinating research on the baffling outbreak, ‘should not have to nickel and dime’ for funds.” The brief appeared next to a column written by gay nurse Bobbi Campbell, who wrote about going to The Shanti Project to get emotional support for his KS.

Bottini’s takeaway from the hearing was that no one really knew how AIDS was transmitted. She was upset. Her friend Ken Schnorr had died just before the hearing and Bottini had to explain to Ken’s distraught mother that he had not been abused at the hospital — the purple bruises on his body were KS lesions. After weeks of governmental inaction, Bottini called Dr. Joel Weisman, Schnorr’s gay doctor, to update the community at a town hall in Fiesta Hall in West Hollywood’s Plummer Park. Weisman had sent gay patients to Dr. Michael Gottlieb and was one of the co-authors on the first CDC public report about AIDS on June 5, 1981.

Bottini later recalled how gay men often thanked her for saving their lives at that packed town hall. Bottini subsequently founded AIDS Network LA, to serve as a clearing house for collecting and disseminating information. But not everyone bought the science-based premise that AIDS was transmitted through bodily fluids — including Bottini’s friend Morris Kight, prompting a deep three-year rift. Nonetheless, groups offering gay men advice on how to have safe sex started emerging, as did peer groups forming for emotional, spiritual and healthcare support. The Bay Area Physicians for Human Rights, Houston’s Citizens for Human Equality and the new Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York City published pamphlets and newsletters.

Panic and denial were wafting in tandem through gay Los Angeles, too. In Oct. 1982, friends Nancy Cole Sawaya (an ally), Matt Redman, Ervin Munro, and Max Drew convened an emergency informational meeting at the Los Angeles Gay Community Services Center on Gay Related Immunodeficiency Disease (GRID, soon to be called AIDS) delivered by a representative from San Francisco’s Kaposi’s Sarcoma Foundation.

“My friends and I were in New York in 1981, hearing stories among friends coming down with this mysterious disease. We realized that back home in L.A. there was no hotline, no medical care, and no one to turn to for emotional support,” Redman told The Advocate’s Chris Bull on July 17, 2001 for a story on the 20th anniversary of AIDS. “For some reason I wasn’t really scared. It was so early on that no one could predict what would happen.”

That quickly changed when the friends realized there was no level of governmental help forthcoming. They set up a hotline in a closet space at the Center, found 12 volunteers and asked Weisman to train them on how to answer questions, reading off a one-page fact sheet. The idea was to “reduce fear” and eventually give out referrals to doctors and others willing to help.

The four also reached out to friends to raise money, netting $7,000 at a tony Christmas benefit to fund a new organization called AIDS Project Los Angeles. They set up a Board of Directors with Weisman and longtime checkbook activist attorney Diane Abbitt as co-chairs. They gaveled their first board meeting to order on Jan. 14, 1983 with five clients. The following month, APLA produced and distributed a brochure about AIDS in both English and Spanish.

Four months later, in May, APLA and other activists organized the first candlelight march in Los Angeles at the Federal Building in Westwood and in four other cities. The LA event was attended by more than 5,000 people demanding federal action. The KS/AIDS Foundation in San Francisco was led by people with AIDS carrying a banner that read “Fighting For Our Lives.” When the banner was unfurled at the National Lesbian and Gay Health Conference that June by activists presenting The Denver Principles, the crowd cried, with a 10-minute ovation.

“If the word ‘empowerment’ hadn’t yet been a part of the health care lexicon, it was about to be,” HIV/AIDS activist Mark S. King wrote in POZ. “The group took turns reading a document to the conference they had just created themselves, during hours sitting in a hospitality suite of the hotel. It was their Bill of Rights and Declaration of Independence rolled into one. It would be known as The Denver Principles, and it began like this: ‘We condemn attempts to label us as ‘victims,’ which implies defeat, and we are only occasionally ‘patients,’ which implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are ‘people with AIDS.’”

While The Denver Principles were injecting self-empowerment into the growing movement of people with AIDS, the Reagan administration was infecting America through mass media association of homosexuality, AIDS and old myths of sexual perversion. Ronald Reagan was keenly aware of his anti-gay evangelical base, appointing Gary Bauer as a domestic policy adviser. Bauer was a close associate of James Dobson, president of the powerful Religious Right group Focus on the Family. Reagan also picked anti-abortion crusader C. Everett Koop as surgeon general — which turned into a mini-scandal when Koop agreed that sexually explicit AIDS education and gay-positive materials should be federally funded for schools. “You cannot be an efficient health officer with integrity if you let other things get in the way of health messages,” Koop told the Village Voice. Koop was slammed by the Moral Majority’s Rev. Jerry Falwell and other anti-gay evangelicals.

But perhaps one of the most egregious examples of the Reagan administration’s homophobic callousness toward people with AIDS came from the persistent laughter emanating from the podium of White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes. On Oct. 15, 1982, less than four weeks after Reps. Henry Waxman and Phillip Burton introduced a bill to allocate funds to the CDC for surveillance and the NIH for AIDS research, reporter Lester Kinsolving asked Speakes about the new disease called A.I.D.S.

KINSOLVING: Larry, does the president have any reaction to the announcement — the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, that AIDS is now an epidemic and have over 600 cases?

SPEAKES: What’s AIDS?

KINSOLVING: Over a third of them have died. It’s known as “gay plague.” (Laughter.) No, it is. I mean it’s a pretty serious thing that one in every three people that get this have died. And I wondered if the president is aware of it?

SPEAKES: I don’t have it. Do you? (Laughter.)

KINSOLVING: You don’t have it. Well, I’m relieved to hear that, Larry. (Laughter.) I’m delighted.

SPEAKES: Do you?

KINSOLVING: No, I don’t….In other words, the White House looks on this as a great joke?

SPEAKES: No, I don’t know anything about it, Lester. What –

KINSOLVING: Does the president, does anybody in the White House know about this epidemic, Larry?

SPEAKES: I don’t think so. I don’t think there’s been any –

KINSOLVING: Nobody knows?

SPEAKES: There has been no personal experience here, Lester.

The exchange goes on like that. For another two years.

On World AIDS Day, Dec. 1, 2015, Vanity Fair debuted a 7:43 documentary directed and produced by Scott Calonico about that 1982 exchange between Kinsolving and Speakes. But Calonico also found audio of similar exchanges in 1983 and 1984 for his film, “When AIDS Was Funny.”

History

LGBTQ historian launches virtual book and film club

Group meets daily via Facebook live stream

The Quarantini Club is a virtual LGBTQ book and film club meeting daily via Facebook live stream at 3 p.m. Participants read their assignments ahead of time while discussions are moderated by award-winning LGBTQ historian Dr. Eric Cervini.

Cervini was a Gates Scholar who graduated summa cum laude from Harvard and received his Ph.D. in history from the University of Cambridge. He is the author of “The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual vs. the United States of America” and his videos have gained tens of thousands of views each week on Instagram.

His first video assignment was the AIDS activism documentary “How to Survive a Plague” and the following week he interviewed celebrated AIDS activist Peter Staley live on Instagram.

Visit ericcervini.com and quarantini.lgbt for more information.

-

South America4 days ago

South America4 days agoDaniel Zamudio murderer’s parole request denied

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoMontgomery County police chief discusses arrest of trans student charged with planned school shooting

-

Commentary5 days ago

Commentary5 days agoWorld ‘isn’t much different today’

-

State Department18 hours ago

State Department18 hours agoState Department releases annual human rights report