Arts & Entertainment

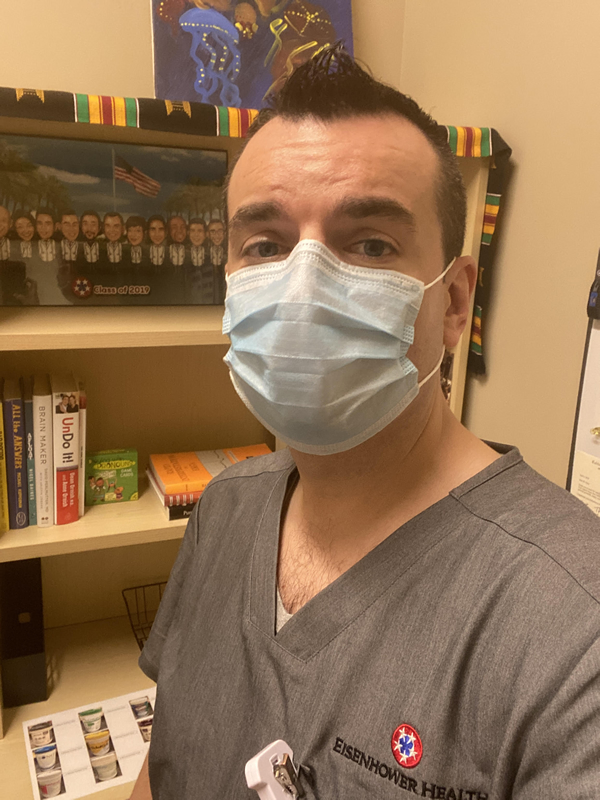

Nonbinary physician fights COVID-19 without legal protections

LGBTQ healthcare workers are stepping up, saving lives

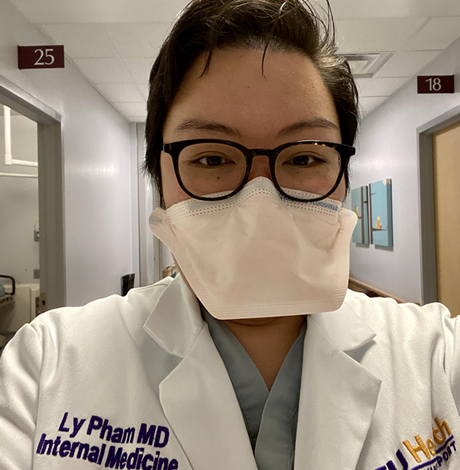

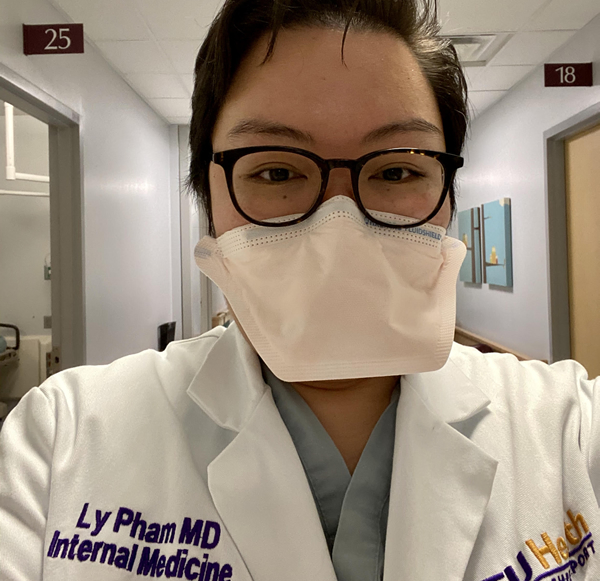

Dr. Scott Nass and Dr. Ly Pham are LGBTQ physicians on the front lines of the pandemic fight, but only one is protected from workplace discrimination. While Nass is fortunate to be a gay cisgender man practicing in California, Pham is a queer nonbinary doctor working in Louisiana without legal protections.

“Shreveport is a level one trauma center similar to Baltimore,” said Pham who uses singular they pronouns. “The hospital was fairly busy before COVID [but the pandemic] added another layer of stress and anxiety.”

Adding to Pham’s stress is the feeling that LGBTQ people are tolerated but not fully accepted into the larger Shreveport community. While HRC reports both Shreveport and New Orleans ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, Louisiana has had a tumultuous history with attempts to mandate a statewide ban.

“I get misgendered all the time,” Pham said before describing a usual day when they arrive at the hospital around 8 a.m. “Mostly by patients coming in and some coworkers. But I’m here to treat the patients and not educate them because they’re in a crisis right now and need to be treated and admitted to the hospital.”

Pham says they allow their patients to interact with them in a way that is emotionally damaging because they feel harms need to be triaged during a crisis. Louisiana governors have sought remedies to this preventable situation.

However, in 2018 the Louisiana Supreme Court struck down Gov. John Bel Edwards’ (D) executive order protecting LGBTQ state employees and contractors from workplace discrimination, according to a report by The Advocate.

The resulting tally from Freedom for All Americans shows Louisiana is one of 28 states where an LGBTQ worker, including essential medical personnel during a global health crisis, can legally be fired or face other negative action on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

“The case of healthcare workers helps illustrate why it is in everyone’s interest that people are able to work regardless of factors that have nothing to do with their ability to do the job,” said Jon Davidson, Freedom for All Americans Chief Counsel. He is also an LGBTQ attorney who attended the Supreme Court arguments on this issue. “I hope the court sees this is not just important to the employees affected, but for society as a whole.”

But not every state will be equally impacted by the ruling.

Davidson explains a Supreme Court ruling on the Bostock v. Clayton County, Altitude Express v. Zarda and Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC cases determining if Title VII protections “on the basis of sex” includes sexual orientation and gender identity won’t affect the 22 states that already have LGBTQ-inclusive nondiscrimination protections.

In April, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam signed into law the Virginia Values Act, expanding nondiscrimination protections in his state to include sexual orientation and gender identity and making it the first state in the South with such inclusions.

“We need every healthcare worker possible saving lives,” Davidson emphasized. “So having protections is both important to keep qualified people in their jobs and it is also important that LGBTQ workers not be worried about who might learn they are LGBTQ. If you have to hide your partner [or who you are] because you’re afraid your employer might find out and you might be fired, that’s unacceptable.”

He added it was “just outrageous and cruel” for healthcare workers to endure such uncertainty during a crisis.

HRC, the Movement Advancement Project and other national policy trackers have noted California, where Dr. Nass encountered the initial waves of the deadly virus, has passed a series of increasingly inclusive statewide measures over the years. Their legislative efforts culminated in the recent Gender Nondiscrimination Act in 2011.

As a result, though Nass also finds the pressures of the pandemic to be “incredibly stressful,” he has not faced the added stress of having to conceal his orientation.

“When I’m not working, I am sheltering in place at home with my husband,” Nass said. “A police officer in Los Angeles who is also on the front lines of the pandemic.”

While their lives are at risk, their jobs and identities are not. However, the situation is very different outside of California.

Pham currently shelters-in-place with their fiancee, who uses both female and nonbinary pronouns and identifies as queer in orientation. The couple bought a two-person hammock so they can lie together under the trees and daydream about a future when they can travel. They are also planning their wedding and an eventual move to Los Angeles.

“It’s spring,” Pham said. “And we are appreciating nature and the flowers blooming and a time to slow down.”

But the rest period doesn’t last long for the physician who graduated in the midst of a global crisis. Pham has been out as an LGBTQ person since attending medical school at the University of Texas in San Antonio. Although Texas is another state without LGBTQ-inclusive workplace protections, Pham was able to find mentors who helped them through their personal journey from self-described butch lesbian to nonbinary as well as through their professional journey from student to physician.

Pham details the rest of their current daily routine with almost machine-like precision.

“I park in a parking lot that is gated using my badge,” Pham said. “There I put on my surgical mask that I have in my car. Parking is in the back of the hospital. I walk to the front. There is only one entrance to the hospital. I try to keep six feet from anyone else and I try to see if anyone else is walking toward the entrance.”

“Everyone feels a little more distant than usual,” agrees Nass in less constrained cadence when discussing his own routine, which begins at 6:30 a.m. “And I’ve worked on speaking more with my eyes now that no one can see me smile under the constant masks.”

Pham is a little more reserved beneath their mask as workplace interactions usually lead to misgendering without reasonable recourse, especially during the crisis.

They arrive at a screening station where they answer a hospital worker’s questions and get their temperature checked. When they pass the checkpoint, they get a sticker on their badge.

“Different colors for different days,” Pham explains. “Before I even get to my office, I usually swing by the ground floor and pick up my N95 mask and face shield, if I’m seeing COVID patients.”

But Pham admits it’s hard to know which patients are COVID positive, so they wear an N95 mask whenever they see patients. They also wipe down their keyboard, desk, chair, mouse, phone — everything in their work area.

Nass may be fortunate when it comes to workplace protections, but his personal equipment seems a little less protective than Pham’s, who works in a larger hospital and more closely with COVID patients.

“I stop at the front desk of the hospital to get an ear-loop mask,” Nass explains. “Not the most protective kind, but those are kept even more securely in particular patient areas.”

Nass notes “on administrative days” he doesn’t usually see much of anyone as access into the office space has been limited to reduce the risk of spreading the virus.

“I am not assigned to take care of confirmed COVID-19 patients in one of the two units we’ve designated for that,” he said. “But we have started to treat every patient, and each other, as though we may be carrying the virus.”

And this may be sound advice, though reminiscent of the early stages of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In March, when PPE distributions were no match for the steady influx of patients in New York City, Kious Kelly, a gay nurse working at Mount Sinai hospital, contracted COVID-19 and died from it.

Kelly’s sister, Marya Patrice Sherron, told BuzzFeed News of a homophobic comment posted to a GoFundMe page set up to help with funeral expenses.

“It was a very, very, very hateful and insensitive comment suggesting that [his death] didn’t matter because he was a gay male.”

Pham faces similar insensitivity from nonbinary erasure even as they struggle to save lives during the crisis.

Pham’s hospital has a dedicated COVID team where they work when they are on call. Pham said in the beginning stages of the crisis it took a week to get test results back so they weren’t certain who was infected and who wasn’t. Now, with better testing, the turnaround has been 24 hours or less.

“We know definitively if they are positive or negative faster, instead of just suspecting that they are,” Pham said. “It helps us triage better.”

Pham also said this is safer for the medical staff since many of the infected are asymptomatic. As a result, everyone is tested regardless of symptoms.

“We stress the importance of social distancing because you don’t know who could test COVID positive and they could be spreading it around unknowingly,” Pham said.

At the end of their shift, Pham removes their gear by following the guidance of a hospital instructional video. They then wipe down their shield with hospital-grade wipes and they toss the mask if it has been visibly soiled.

After cleaning themselves and their workstation again, they wear a surgical mask down to their car. They then clean themselves and the interior of their car with alcohol again. When they get home, they keep a six feet distance from their fiancee and toss their clothes into the washing machine before jumping into the shower.

When it is safe, the two of them can finally relax together and reconnect by cooking, watching Netflix or daydreaming in their shared hammock.

Nass similarly ends his day with a trip to the washing machine and shower before collapsing on the couch with his husband and Boston Terrier. In the hour or two before he falls asleep he catches up on “The Magicians” or “Schitt’s Creek.”

“Sometimes I eat dinner,” he said in a rare consideration of his own health.

“LGBTQ healthcare workers are stepping up to save lives in this crisis,” said Hector Vargas, the executive director of GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality, an LGBTQ medical professionals advocacy organization. “It’s long past time we step up for them to make sure they’re protected under the eyes of the law.”

Team DC, the umbrella organization for LGBTQ-friendly sports teams and leagues in the D.C. area, held its annual Night of Champions Awards Gala on Saturday, April 20 at the Hilton National Mall. The organization gave out scholarships to area LGBTQ student athletes as well as awards to the Different Drummers, Kelly Laczko of Duplex Diner, Stacy Smith of the Edmund Burke School, Bryan Frank of Triout, JC Adams of DCG Basketball and the DC Gay Flag Football League.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

The 2024 National Cannabis Festival was held at the Fields at RFK Stadium on April 19-20.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

Covering the @NatlCannaFest at RFK Stadium for @WashBlade . Stop by the LGBTQ+ booth and pick up a paper if you are here. pic.twitter.com/is7hnsaPns

— Michael Patrick Key (@MichaelKeyWB) April 20, 2024

Theater

‘Amm(i)gone’ explores family, queerness, and faith

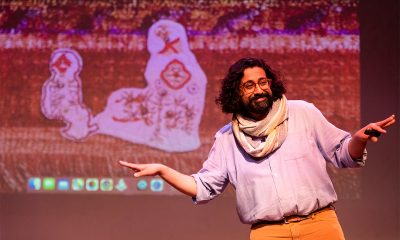

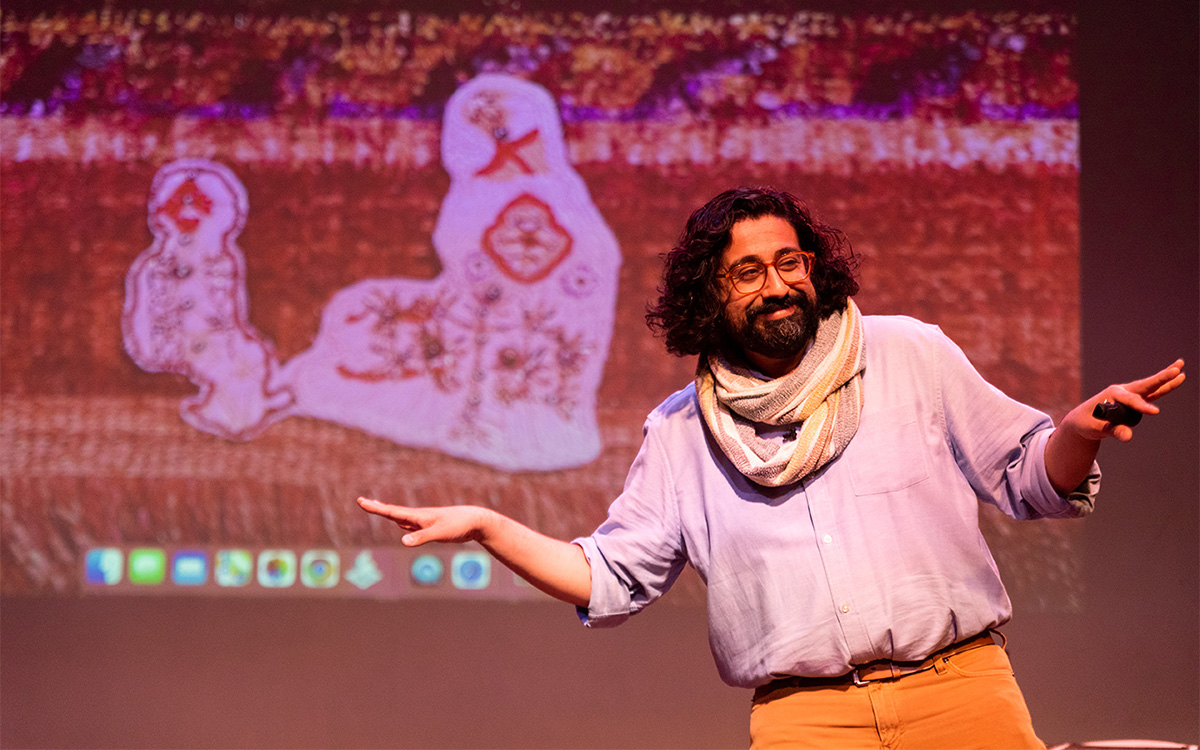

A ‘fully autobiographical’ work from out artist Adil Mansoor

‘Amm(i)gone’

Thorough May 12

Woolly Mammoth Theatre

641 D St., N.W.

$60-$70

Woollymammoth.net

“Fully and utterly autobiographical.” That’s how Adil Mansoor describes “Amm(i)gone,” his one-man work currently playing at Woolly Mammoth Theatre.

Both created and performed by out artist Mansoor, it’s his story about inviting his Pakistani mother to translate Sophocles’s Greek tragedy “Antigone” into Urdu. Throughout the journey, there’s an exploration of family, queerness, and faith,as well as references to teachings from the Quran, and audio conversations with his Muslim mother.

Mansoor, 38, grew up in the suburbs of Chicago and is now based in Pittsburgh where he’s a busy theater maker. He’s also the founding member of Pittsburgh’s Hatch Arts Collective and the former artistic director of Dreams of Hope, an LGBTQ youth arts organization.

WASHINGTON BLADE: What spurred you to create “Amm(i)gone”?

ADIL MANSOOR: I was reading a translation of “Antigone” a few years back and found myself emotionally overwhelmed. A Theban princess buries her brother knowing it will cost her, her own life. It’s about a person for whom all aspirations are in the afterlife. And what does that do to the living when all of your hopes and dreams have to be reserved for the afterlife?

I found grant funding to pay my mom to do the translation. I wanted to engage in learning. I wanted to share theater but especially this ancient tragedy. My mother appreciated the characters were struggling between loving one another and their beliefs.

BLADE: Are you more director than actor?

MANSOOR: I’m primarily a director with an MFA in directing from Carnegie Mellon. I wrote, directed, and performed in this show, and had been working on it for four years. I’ve done different versions including Zoom. Woolly’s is a new production with the same team who’ve been involved since the beginning.

I love solo performance. I’ve produced and now teach solo performance and believe in its power. And I definitely lean toward “performance” and I haven’t “acted” since I was in college. I feel good on stage. I was a tour guide and do a lot of public speaking. I enjoy the attention.

BLADE: Describe your mom.

MANSOOR: My mom is a wonderfully devout Muslim, single mother, social worker who discovered my queerness on Google. And she prays for me.

She and I are similar, the way we look at things, the way we laugh. But different too. And those are among the questions I ask in this show. Our relationship is both beautiful and complicated.

BLADE: So, you weren’t exactly hiding your sexuality?

MANSOOR: In my mid-20s, I took time to talk with friends about our being queer with relation to our careers. My sexuality is essential to the work. As the artistic director at Dreams of Hope, part of the work was to model what it means to be public. If I’m in a room with queer and trans teenagers, part of what I’m doing is modeling queer adulthood. The way they see me in the world is part of what I’m putting out there. And I want that to be expansive and full.

So much of my work involves fundraising and being a face in schools. Being out is about making safe space for queer young folks.

BLADE: Have you encountered much Islamophobia?

MANSOOR: When 9/11 happened, I was a sophomore in high school, so yes. I faced a lot then and now. I’ve been egged on the street in the last four months. I see it in the classroom. It shows up in all sorts of ways.

BLADE: What prompted you to lead your creative life in Pittsburgh?

MANSOOR: I’ve been here for 14 years. I breathe with ease in Pittsburgh. The hills and the valleys and the rust of the city do something to me. It’s beautiful, it’ affordable, and there is support for local artists. There’s a lot of opportunity.

Still, the plan was to move to New York in September of 2020 but that was cancelled. Then the pandemic showed me that I could live in Pittsburgh and still have a nationally viable career.

BLADE: What are you trying to achieve with “Amm(i)gone”?

MANSOOR: What I’m sharing in the show is so very specific but I hear people from other backgrounds say I totally see my mom in that. My partner is Catholic and we share so much in relation to this.

I hope the work is embracing the fullness of queerness and how means so many things. And I hope the show makes audiences want to call their parents or squeeze their partners.